Introduction

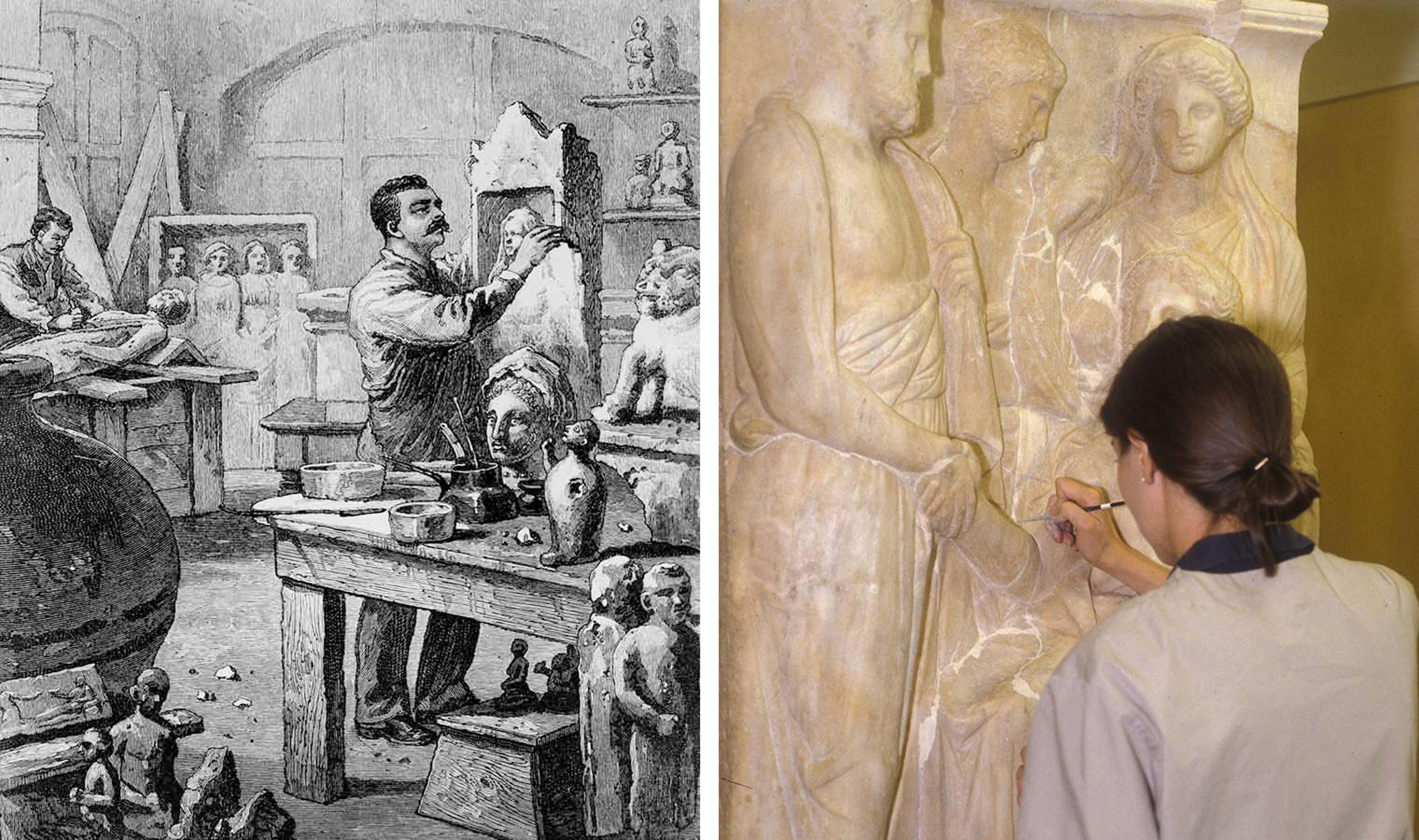

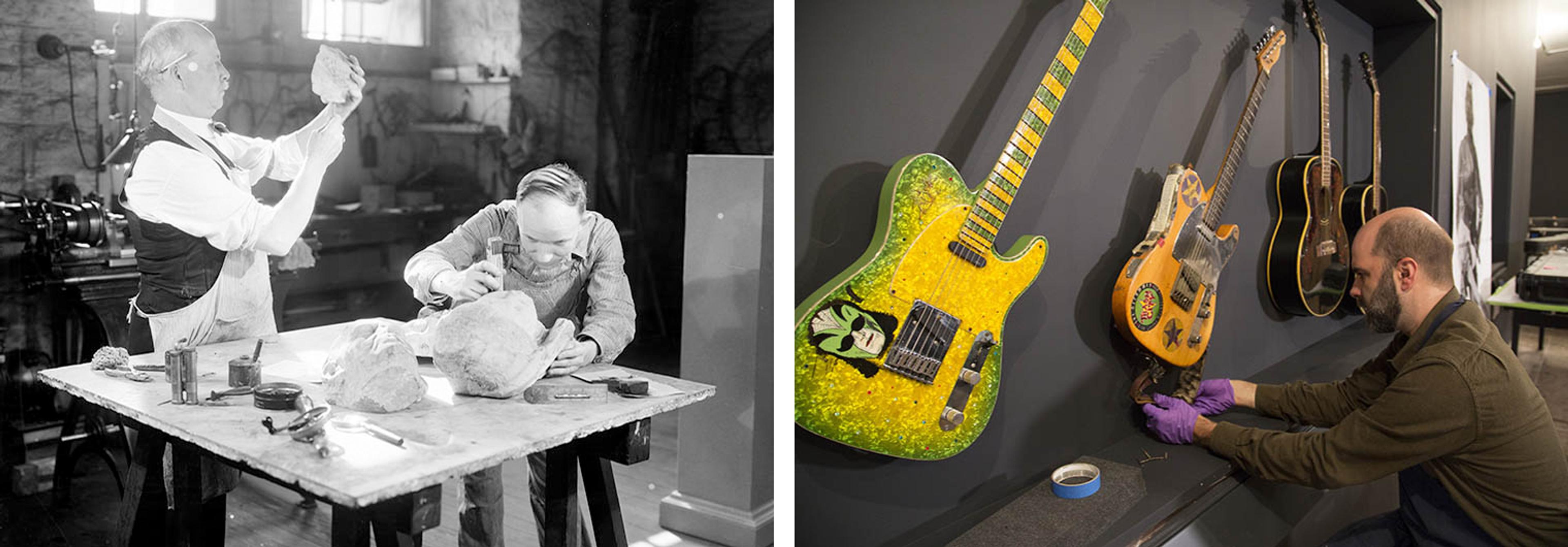

Repair Shop, November 4, 1936. During the first seventy years of the Museum’s existence, most works of art other than paintings were stabilized and restored by skilled craftsmen and semi-skilled workmen, in workshops such as this one under the supervision of the building superintendent.

Since 1870, The Metropolitan Museum of Art has dedicated substantial resources to the preservation, technical study, and safe display of its collection. Today, nearly one hundred conservators, conservation scientists, and conservation preparators are tasked with these responsibilities, building upon the efforts of a diverse ensemble of craftsmen, restorers, scientists, directors, and curators working in dispersed workshops, laboratories, curatorial offices, and departmental study rooms throughout the building during the Museum’s earlier years.

Left: This 1880 illustration from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine shows Charles Baillard—a trained watchmaker, and the first truly recognizable figure in the history of conservation practice at the Museum—working on stone sculpture in the Cesnola Collection. Right: Conservator Linda Borsch treating a late Classical Greek funerary stele in 1997.

Present-day conservation specialists work in studios and laboratories situated in independent departments dedicated to objects (three-dimensional works of art), paintings, works on paper, photographs, textiles, and scientific research, and in The Costume Institute, Thomas J. Watson Library, and the Departments of Arms and Armor; Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas (for textiles); and Asian Art (for East Asian paintings).

Several themes exemplify the development of conservation practice at The Met. The impact of charismatic and progressive directors and curators was significant in earlier years, before the field of conservation emerged as a distinct profession with well-trained practitioners. Nowadays conservators receive rigorous interdisciplinary academic and practical training, and they cultivate skills and knowledge to gain competency in one or more of a wide range of sub-specialties. This sets them apart from the diverse cohort of early practitioners who were often self-taught, though not necessarily unskilled, and who wore multiple hats.

The emergence of conservation as an academic profession has fostered collaboration among the conservation departments, including the Department of Scientific Research, and scholarly exchange and collaboration with curatorial staff and educators. Conservation and conservation science play a role in every aspect of the Museum’s core mission to "[collect, study, conserve, and present] significant works of art across all times and cultures in order to connect people to creativity, knowledge, and ideas."

Perhaps the most significant change in the field of conservation, particularly over the last six decades, is the evolution of a sensibility that privileges the primacy of the works of art as an expression of the artist’s intent, and their manufacture and materials as a reflection of technological style.

Left: MMA, Interior Shops, Upholstery Shop, Wing F, Basement, 1926. In the days of the workshops, women apparently only worked with textiles of various kinds, including upholstery and tapestries. Right: Kathryn Gill, the Museum’s first professional upholstery conservator, treats one of two settees from the Seehof suite in 1988. The number of women in all conservation specialties has grown exponentially over the decades.

I. The Early Years: "They Also Serve" (1870–1940)

During its first seven decades, most tasks relating to the preservation, restoration, and mounting of artworks were carried out by craftsmen (and the occasional woman) in workshops on the Museum’s ground floor under the aegis of a superintendent, who also managed the shops for the carpenters, metalworkers, and other workmen who maintained the building and its furnishings.

In 1906, the Department of Egyptian Art was established, and a team was sent to excavate at Thebes in Upper Egypt. Over the next thirty years, the Museum acquired thousands of artifacts from excavations there and elsewhere in Egypt. This influx of highly unstable new finds spurred the Museum to seek out means of stabilizing them. Scientists such as William E. Kuckro (d. 1961) and Colin G. Fink (1881–1953) were engaged to investigate the deterioration and preservation of archaeological stone artifacts and archaeological bronzes. Fink’s electrochemical methods were adopted all over the world but now are long out of favor. As a result of his quest for permanency at any cost, the metal artifacts that he treated are chemically stable for the most part but have unattractive surfaces that evoke neither their original nor as-excavated appearance.

Sometimes it was necessary to stabilize newly excavated finds granted the Museum before they could be transported. In this 1924 footage from the Museum’s excavation at Thebes, Egyptologist Herbert E. Winlock applies wax consolidants to a wooden coffin and removes the excess.

These scientific consultants were engaged by the Museum's third director, Edward Robinson (1858–1931), a classical archaeologist by training. During his twenty-one-year tenure (1910–31), he brought new analytical and imaging tools to bear on questions of authenticity, dating, and the extent of prior restorations. The expanding role of science is seen in Robinson's call in 1925 for a national laboratory to ensure that the treatment of artworks would be of “the highest scientific character.” His successor, Egyptologist Herbert E. Winlock (1888–1950), who himself stabilized new finds while on site, corresponded regularly with preservation specialists on thorny problems, and when he became director in 1932, hired Arthur H. Kopp (1900–1938), the Museum’s first resident scientist. Kopp continued Fink’s research into electrochemical methods, but also devoted much time to restoring and analyzing objects of metal, stone, faience, and other materials, and his activities are well documented in laboratory notebooks that continue to serve as a valuable staff resource. The Museum avoided hiring a resident scientist for decades following Kopp’s death in a laboratory fire. Starting in the late 1920s while still a curator at The Cloisters, James J. Rorimer (1905–1966), the Museum’s sixth director, also personally carried out a variety of treatments and technical investigations.

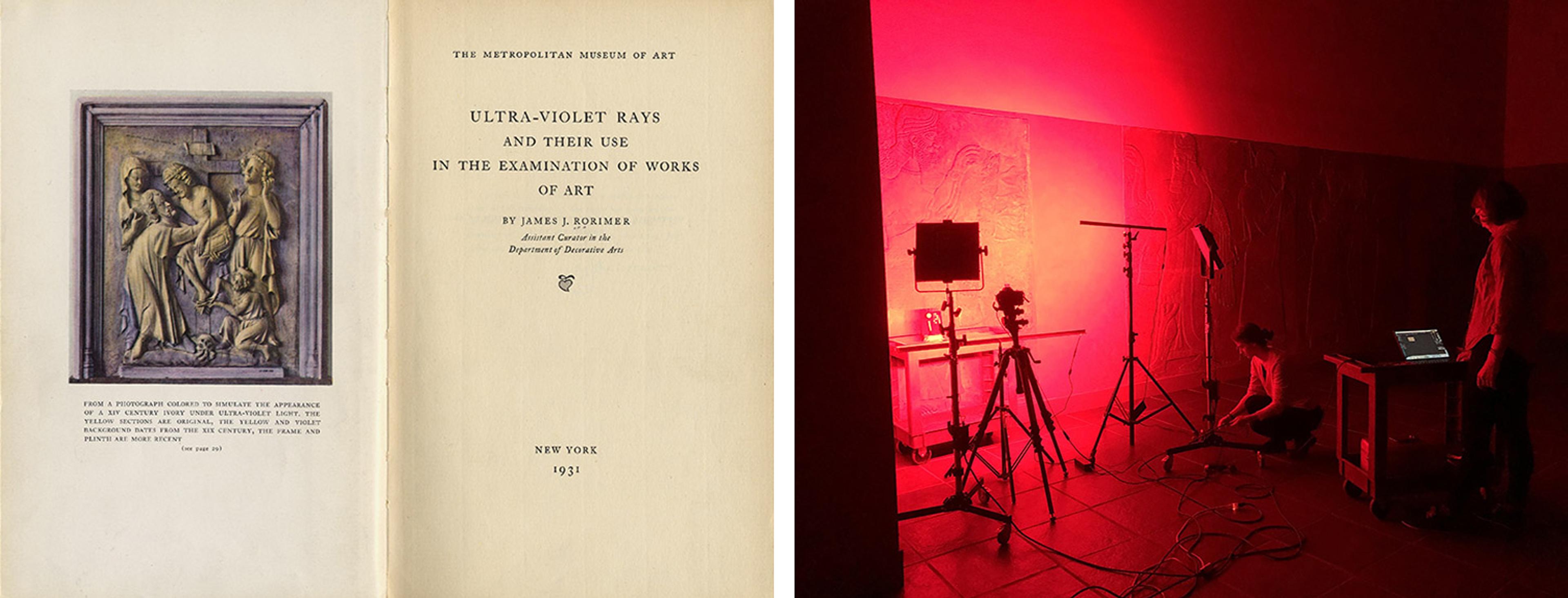

Left: James Rorimer, before he became director in 1955, was actively engaged in both restoration work and technical research. The ivory panel in the frontispiece of his groundbreaking 1931 study on the examination of works of art using ultraviolet light was hand colored to reflect its appearance when illuminated. Right: Rorimer’s legacy lives on in multiband spectral imaging, a recently codified suite of photographic processes used for recording condition, documenting prior and new treatments, technical examination, and preliminary materials characterization. Conservator Anna Serotta (right) and Mellon Fellow Chantal Stein document traces of Egyptian blue pigment on the Museum’s Assyrian limestone reliefs in the Ancient Near Eastern Art galleries using visible-induced infrared luminescence imaging.

The Department of Paintings was established in 1886. With notable exceptions—for example, curator Roger Fry (1866–1934) was defended in a 1906 article of the Museum’s Bulletin for his cleaning of a Rubens painting that had been publicly criticized by the director of the Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo—care of this collection fell to freelance paintings restorers such as H. A. Hammond Smith (1860–1927) and Stephen S. Pichetto (1887–1949), who enjoyed a more elevated status (and a third-floor studio with natural daylight) than the artisans working on other materials on the ground floor. Fry was the first curator, though certainly not the last, who restored works in the Museum's collection, often with unfortunate results. The incident with the Rubens painting, and its attendant press, reflected the public interest in restoration work carried out at The Met. Scrutiny in this case was minor compared to a media frenzy that started in 1890 and lasted for several years after public allegations that Cypriot stone sculpture in the Cesnola Collection had been fraudulently restored by Charles Baillard (d. 1916), the Museum's first restorer.

Left: Interior, Shops, Painters Restorer’s Studio, Wing B, Floor III, 1936. A master at self-promotion, self-taught but highly respected, Stephen S. Pichetto offered his services as a paintings restorer to the Museum in 1929 and worked there on a part-time basis until his death in 1949. He is seen here working on Raphael’s Agony in the Garden. The press on the left was used for the now outdated practice of attaching rigid supports known as cradles to the reverse of panel paintings. Right: George Bisacca, a conservator specializing in the care of panel paintings, in 2007 before the most recent refurbishment of the Paintings Conservation studios. During his decades at the Museum, Bisacca not only maintained the collection—which included treating paintings suffering the deleterious effects of being attached to old-fashioned cradles—but also helped introduce modern practice to frame conservation. In 2009, the Museum’s first gilding conservator dedicated to frames joined the department.

International specialists were engaged for specific projects. Many archaeological metal objects were sent to the renowned Parisian firm of Léon André for cleaning and restoration; Japanese craftsmen Okabe Kakuya (1873–1918) and Rokkaku Shisui (1867–1950), who had worked previously at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, treated the Museum’s collection of Japanese metal, lacquer, and wood sculpture in 1908.

After serving in an honorary capacity in the Decorative Arts Department, Renaissance man and collector Bashford Dean (1867–1928) was appointed curator in the Department of Arms and Armor upon its establishment in 1912. Jacob Merkert (d. 1933) had maintained the collection since 1894, but Dean saw the need for a trained armorer who could reproduce missing and damaged steel components. In 1909, he hired a Frenchman, Daniel Tachaux (1857–1928), heir to the traditional practice of armor making in Europe. Until 1919, Tachaux worked both at the Museum and in Dean’s private armory in his home. The German armorer Leonard Hugel (1877–ca. 1935) and his nephew Leonard Heinrich (ca. 1900–1966) continued the same arrangement until Dean’s death in 1928, when they came to work full-time in the Museum, joined by a local man, Harvey Murton (1907–2004), who trained in Dean’s armory from age twelve. In keeping with the workshop practices of the day, artists and craftsmen restored other works in the diverse collection: Stanley J. Rowland (1891–1964), for example, a draftsman who went on to become a successful mural painter, treated polychrome wood shields.

MMA Interiors, Workshops, Armor Repair Shop, Wing E Room 105, Basement Floor, 1937. Seen here are armorers Harvey Murton (far left) and Leonard Heinrich (second from right).

II. The Middle Years: Consolidation (1940–1960)

In 1940, Francis Henry Taylor (1903–1957), the Museum's fifth director, arrived from the Worcester Art Museum, bringing with him a tradition of conservation innovation fostered in the Boston area by Harvard's Fogg Art Museum. He requested a curatorial investigation into the Museum's restoration practices and learned that the “repair” of three-dimensional works, including metal, stone, ceramics, and furniture, was carried out by men who for the most part were self-trained—having been promoted from maintenance positions—working under the direction of the building superintendent. The report further stated: “Quality of work generally satisfactory to curators. Working conditions poor. Technical direction, as distinct from mechanical supervision, practically non-existent.”

In addition to active service, many members of the Museum's staff contributed to the war effort during World War II. Most famously, James Rorimer was among the "Monuments Men"—there were also women, one of whom, Edith Standen (1905–1998), later became a curator of textiles at the Museum—who secured artworks looted during World War II. Closer to home, conservator Murray Pease (1903–1964) played an important role in safeguarding works endangered in the event of a direct attack on the North American mainland. A singular contribution to the war effort, however, was that of the Museum's armorers, who worked with curators in the Department of Arms and Armor, as they had during World War I, to design and produce prototypes for defensive armors at the request of the United States government.

Leonard Heinrich working on a helmet for the United States Army, 1942–45.

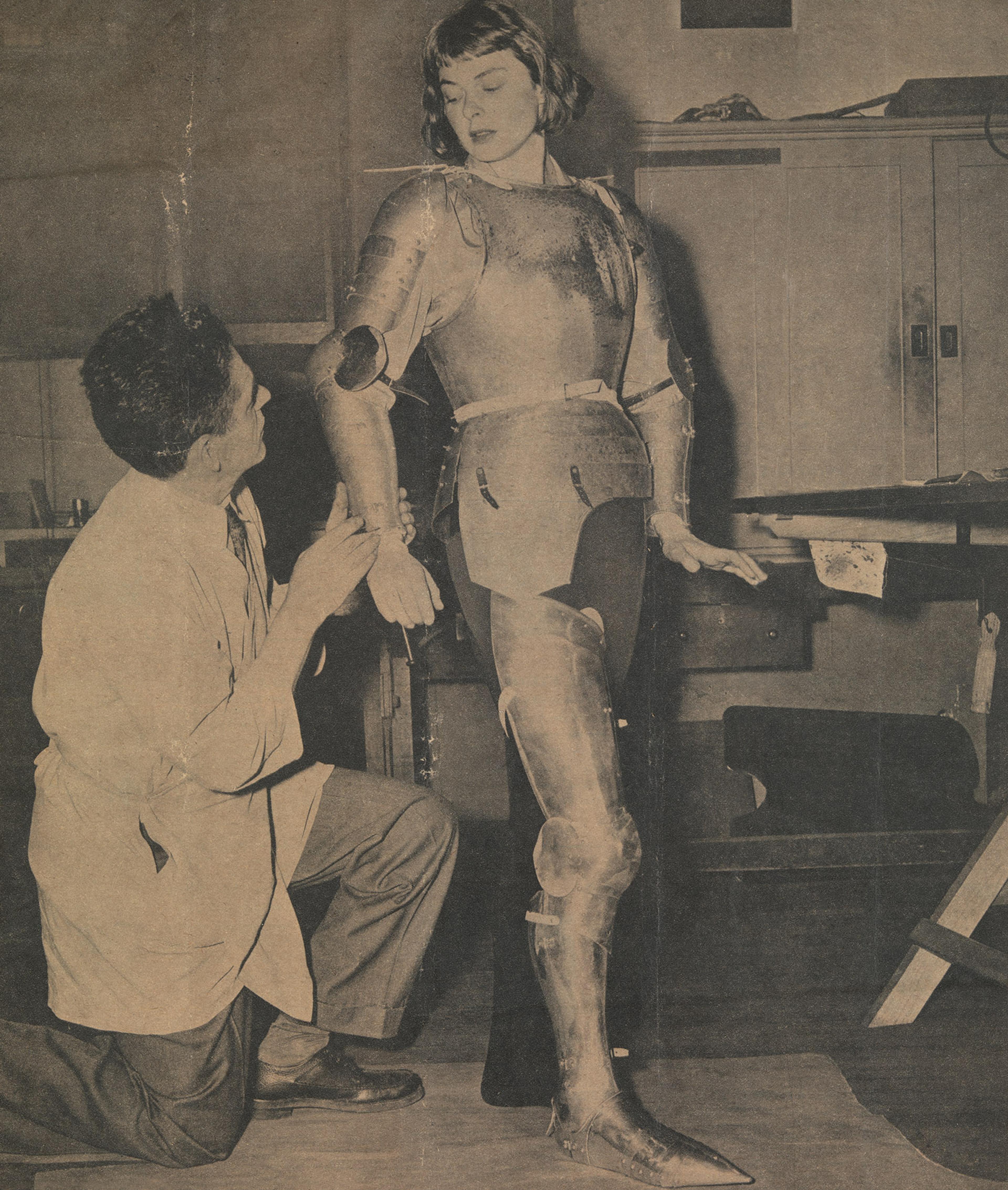

Having contributed to the war effort during World War II, Heinrich applied his expertise, hand skills, and Tachaux's tools to designing and fabricating a suit of armor that Ingrid Bergman wore in the title role of the 1948 film Joan of Arc. Made of aluminum, the armor weighs about one third of what a similar suit in steel might weigh.

In 1941, Taylor had named Pease, a Fogg alumnus, associate curator of the Sub-Department of Conservation and Technical Research, charging him to create a centralized department for conservation. Together, they laid the foundation for modern conservation practice through the introduction of standardized “request for treatment” forms, protocols for documentation, condition checks for outgoing loans, and handling guidelines, which formed the basis of the 1946 publication, Care and Handling of Art Objects, by registrar Robert Sugden (1908–1953). The most recent update, combining the expertise of more than sixty conservators, curators, and other museum specialists, was published on the Museum’s website in 2020. In 1949, the sub-department was renamed Technical Laboratory and granted full departmental status; Pease was appointed Conservator in 1956, the first time this title was used in the Museum.

Pease was trained in the restoration of paintings, and his interests and expertise also extended to technical research. He made few changes in the treatment of three-dimensional objects, and having combined the existing workshops, he still supervised the same craftsmen already working in the Museum. In 1947, he hired an assistant, Kate Lefferts (1911–2000), who managed the Laboratory and restored paintings. Unlike Lefferts and two specialists for paintings who were also hired in the 1940s, employees in the workshops were not mentioned in the Museum's annual reports until the early 1960s, despite Pease's attempts to raise their salaries and status. They remain for the most part anonymous. Although Pease had stressed the need for trained scientific staff, it was only in 1970 that Pieter Meyers was engaged as a research chemist.

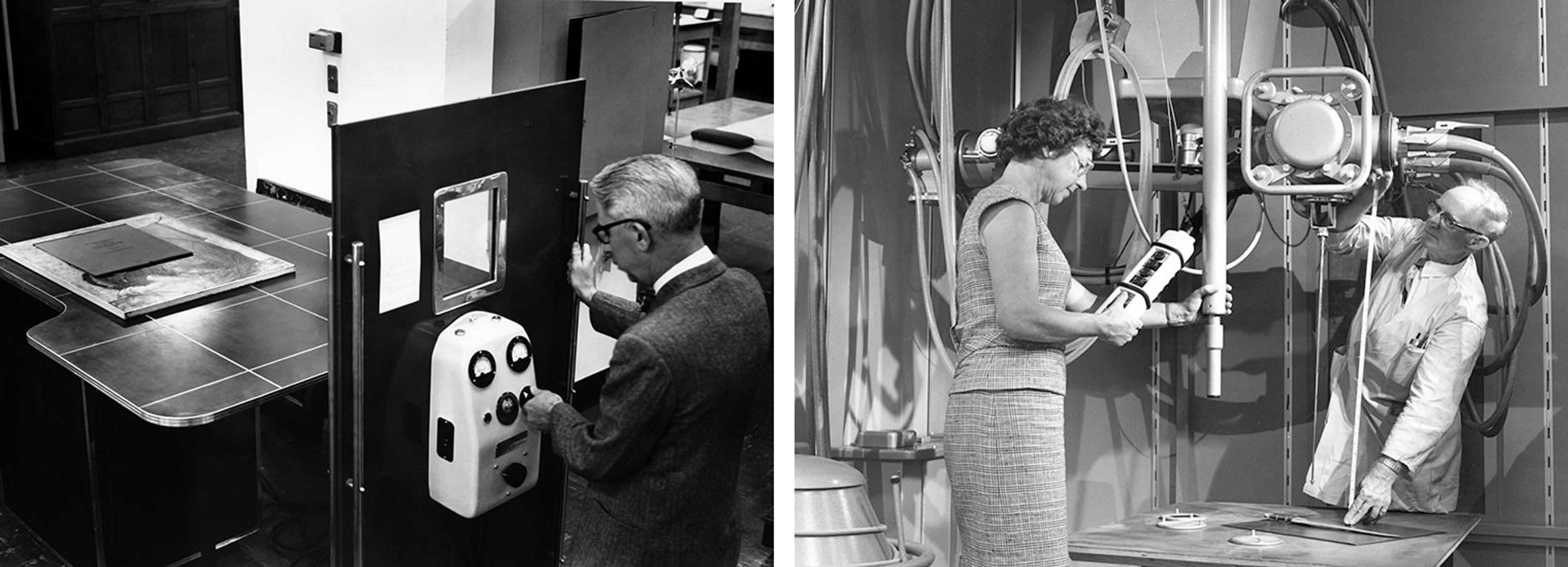

Left: Starting in the 1920s, Alan Burroughs, a pioneer in the radiographic study of paintings at the Fogg Art Museum, employed portable equipment to take X-rays of several hundred works by Old Masters in the Museum’s collection. Seen here in 1954, Murray Pease radiographs a painting on a newly acquired unit, possibly the Museum’s first. Right: Kate Lefferts and Patrick Staunton in 1968, when the Museum acquired its first X-ray unit powerful enough to radiograph especially massive artworks, such as large stone statuary, or materials (like metal) of high atomic weight. This acquisition was funded by Museum trustee Charles Wrightsman, motivated in part by the potential benefit to the NYU students who attended classes in the department and often returned as interns.

Pease also advocated for the emerging profession as a founding member the International Institute for the Conservation of Museum Objects in 1950, precursor of the International Institute of Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (IIC), which remains an influential association of conservation specialists. Pease later headed the committee that drew up guidelines for basic standards of professional practice and ethics accepted in 1963 by the membership of the American Group of the IIC, now known as the American Institute for Conservation (AIC).

Full professionalization required professionally trained conservators. It was not until 1960, decades after the demise of the Fogg's training program for paintings conservators, that the first graduate-level training in the United States for conservators of three-dimensional objects, textiles, works on paper, as well as paintings, was offered at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts Conservation Center. The students received foundational knowledge of all specialities as part of an interdisciplinary education combining art history and archaeology, natural sciences, historic technology, and practical experience in examining and treating works of art. Other opportunities for training arose with the establishment of the Cooperstown Graduate Program in the Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works in 1970 (now part of SUNY Buffalo State College) and the Winterthur-University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation in 1974.

III. The Rise of Professionalism (1960–1976)

The appointment of Hubert von Sonnenburg (1928–2004) in 1961 as Conservator of Paintings in the Department of European Paintings marked a gradual transition that led to the creation by the mid-1970s of four independent conservation departments for paintings, works on paper, textiles, and three-dimensional objects. Sonnenburg replaced the previous generation of practitioners’ “dispassionate objectivity” with an aesthetic approach. His successor, John Brealey (1925–2002), who took up his position in 1975, envisioned the department as a center for collaboration and training that included art historians and scientists, where paintings would be treated as artworks and not as clinical specimens. With funding from the Sherman Fairchild Foundation, a rehoused and reequipped facility opened in 1980. This also marked the beginning of the Foundation’s sustained financial support of conservation initiatives in the Museum.

Conservation efforts have always focused heavily on new acquisitions. Left: Hubert von Sonnenburg restoring Tiepolo’s The Triumph of Marius in 1966, one year after it was purchased. Right: Michael Gallagher, Sherman Fairchild Chairman of Paintings Conservation, in 2015, varnishing a work by Charles Le Brun acquired by the Museum in 2014.

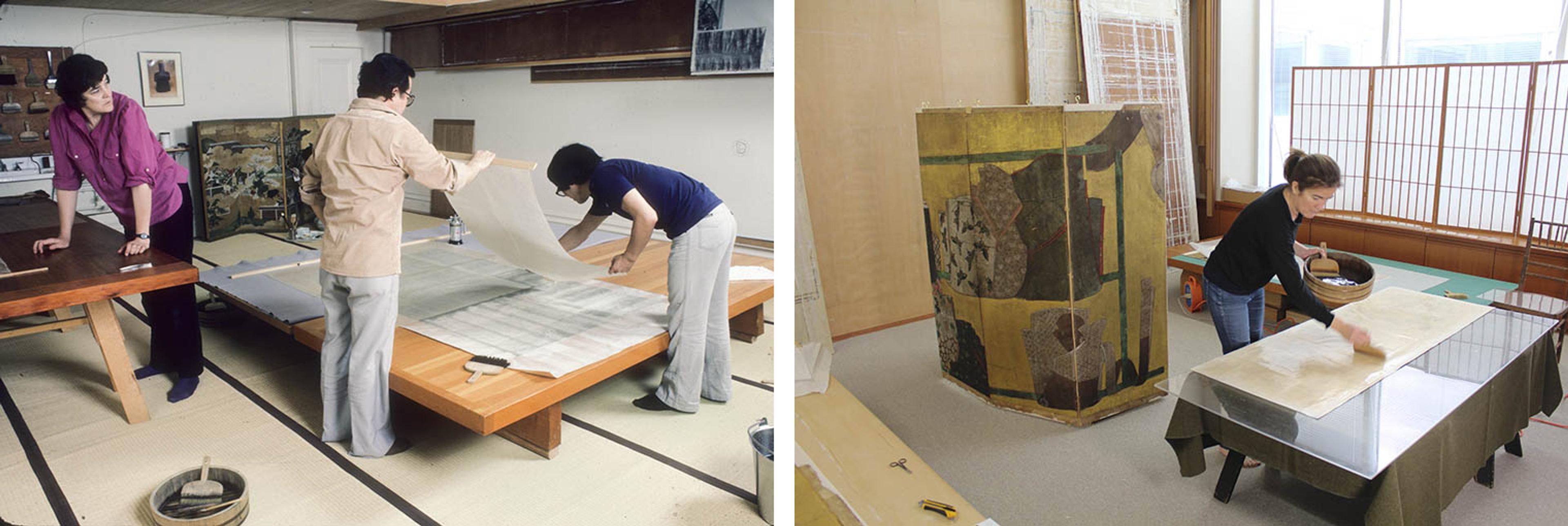

Already at the beginning of the twentieth century, the Museum periodically recruited specialists from Japan to restore East Asian artworks. A dedicated studio for East Asian paintings—the third established in the United States—was set up in the “high attic” above the domes of the Great Hall in 1966, when Mitsuhiro Abe (1937–2015), a Japanese paintings restorer trained in the renowned Oka Bokkodo Studio in Kyoto, was invited to join the staff. Growth of expertise in this area was a priority of the Museum’s Consultative Chairman for Asian Art, Wen Fong (1930–2018), who in 1978 hired Takemitsu Oba and Sondra Castile, both trained in the same Kyoto studio. Currently five conservators trained in China or Japan treat scroll paintings, folding screens, and related materials from East Asia and the Himalayas. Four of these positions are endowed, reflecting the strong support of departmental donors for excellence in conservation and conservation training.

Left: Conservators Sondra Castile, Mitsuhiro Abe, and Takemitsu Oba (from left to right), are seen here in the “high attic,” applying a kozo paper lining to a scroll mounting silk. This photograph dates to around 1985. Right: Conservator Jennifer Perry, Mary and James Wallach Family Conservator of Japanese Art, in 2017, in the East Asian Paintings Conservation Studio, which was relocated to its current location in the Department of Asian Art in 1999 with funding from the C. V. Starr Foundation.

Paper conservation pioneers had already taken up residence in the Museum in 1941, when Merritt Safford joined the Department of Prints as a restorer. At the same time, Minna Horwitz (1899–1984), who had trained at the Fogg, split her time between The Met and the Morgan Library, where she and Pease set up studios for treating works of art on paper. She also served as Safford’s mentor. In the early 1960s, a new studio above the recently completed Watson Library was outfitted, in proximity to the then-separate Departments of Prints and Drawings. Safford received a Conservator title in 1964 when the departments were combined. Safford was a strong advocate for professionalization of conservation practice: he hired academically trained conservators and fought for changes in their titles from restorer to conservator in order to maintain equity within the Museum’s hierarchy, and to reflect their advanced training and expertise.

Left: Minna Horwitz (second row, third from left) with other staff members at the Fogg Museum in the 1940s. Horwitz had studied painting with William Merritt Chase at the Art Students League in New York, and was working as an art teacher in Boston, when she met Margaret H. Stout, wife of conservation pioneer and "Monuments Man" George L. Stout. Horwitz began her career as a volunteer at the Fogg, where Stout headed the conservation laboratory, and returned to New York in 1950 when recruited by Louise Burroughs, The Met's curator of drawings. Right: Among the reforms introduced by Taylor and Pease was routine condition checks for incoming and outgoing loans. Here, in Storeroom One, paper conservators Margaret Lawson and Betty Fiske examine loans for the exhibition Counterparts: Form and Emotion in Photographs, which was mounted at The Met in 1982 and then traveled to museums in Cincinnati and Dallas.

When Kate Lefferts succeeded Pease in 1964, the Conservation Department, as it was now known, was responsible for all three-dimensional works (other than arms and armor and musical instruments), textiles, scientific investigation, and general conservation practice. Lefferts retired in 1970, and her successor—for a brief period until his own retirement—was Walter (Ed) Rowe. Rowe was so highly respected for his hand skills and knowledge of historic techniques that he received the perhaps singular honor (for a restorer) of an article profiling his work in the Museum's Bulletin, illustrated with a photograph made by a popular portrait photographer and now in the collection of the National Gallery of Ontario. Curators had already expressed their concern over the quality of work carried out under Lefferts's direction, and in the years following, standards diminished further with the evolution of small enclaves and sub-departments without consistent oversight. By all accounts, many curators requested specific treatments—not necessarily the most suitable—or demanded restorations that would today be deemed excessive or misleading, and many of their complaints reflected unrealistic expectations regarding the amount of time required to complete their requests. Still, due in part to their membership in international museum organizations and to their various professional and personal connections to the Institute of Fine Arts, the more enlightened among them had recognized that conservation practice and training were changing rapidly.

In 1976, acknowledging imminent need for a professional conservation team for the ongoing reinstallation of the Egyptian collection, the Museum recruited James H. Frantz, an alumnus of the Conservation Center at the Institute of Fine Arts. Over his twenty-seven-year tenure, Frantz transformed the department and revitalized the practice of objects conservation and scientific research. Change came immediately with the hiring of professional conservators for archaeological, ethnographic, and historic works of art, including specialists in furniture, historic interiors, gilding, and upholstery conservation. Frantz also hired dedicated mount makers, today officially known as conservation preparators, to design and fabricate exhibition, storage, and travel mounts in keeping with modern conservation standards.

Left: Repair Shop, Wing B, Room 135, Basement Floor, 1926. Most of the repairers in the early workshops were non-specialists. These “mount makers” apparently also restored ceramics, to judge from other photographs made at the same time. Right: Conservation preparator Warren Bennett installs guitars for the 2019 exhibition Play it Loud. Conservation preparators are specialists based in the Departments of Objects Conservation who create customized mounts for the Museum’s collection when on display, in storage, and during travel; they also assure that the works are safely installed. As the Museum’s calendar of temporary exhibitions has expanded, conservation preparators spend a substantial amount of time making mounts and installing works of art on loan.

Scientists also joined the department, working with conservators to characterize materials and mechanisms of deterioration, and to develop new treatments, using newly acquired or upgraded scientific instrumentation. A visiting committee established in the early 1980s provided financial support and advocacy within the Museum to ensure continued growth in expertise and infrastructure, and in 1992, a new facility opened to house this expanding roster of specialized staff members and ever more sophisticated equipment, with major funding from the Sherman Fairchild Foundation. The Foundation subsequently funded the studio for objects conservation that opened at The Cloisters in 2002.

Research physicist Gary Carriveau in 1979 with the Museum’s first X-ray fluorescence spectrometer, affectionately known as “death-ray.”

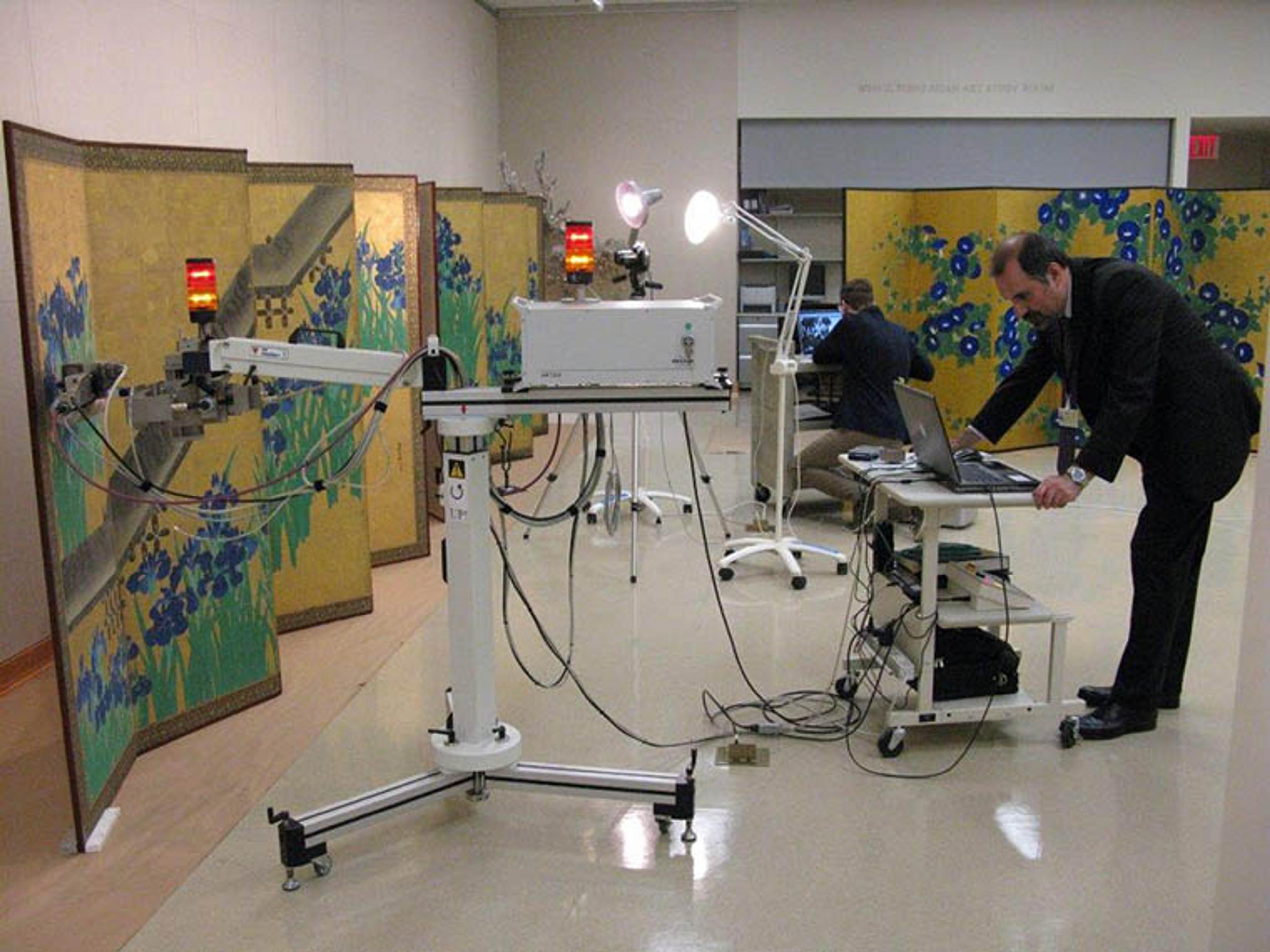

With the establishment of an independent Scientific Research Department, the Museum has acquired new expertise and new instrumentation. Marco Leona, the David H. Koch Scientist in Charge, is seen here carrying out instrumental analysis on Irises at Yatsuhashi (Eight Bridges) in 2012. This mobile X-ray fluorescence spectrometer is one of four different units in the Department that can be used in the lab, in the galleries, in storerooms, as in this case, or off-site, for non-destructive elemental analysis.

Textile conservation, which was also part of the old workshop system and later administered by Pease and Lefferts in turn, had become an independent department in 1973 under the leadership of Nobuko Kajitani. Kajitani, who was trained in conservation at the Textile Museum in Washington D.C., came to The Met as a restorer in 1966. According to her oral history recorded in 2002, the tapestries at that time were being cared for by “needlewomen,” but other textiles were largely neglected: her predecessors, Mrs. Burke and Mrs. Sullivan, were using accessioned French and Indian printed cottons to make curtains for period rooms in the American Wing. Kajitani oversaw the physical and professional expansion of the department. In 1995, with funds provided by the Antonio Ratti Foundation, a new laboratory was inaugurated along with a centralized research facility, the Antonio Ratti Textile Center and Research Library. Designed to provide optimal conditions for storing and viewing textiles, the Ratti Center is currently maintained by five collections specialists under curatorial management coordinating with the Department of Textile Conservation. The Department of Textile Conservation and the Ratti Center were early adopters of the Museum's collections database derived from existing catalogue card information. Today, a robust online catalogue provides scholars with high-resolution images, documentation, and historical information for textiles in twelve curatorial collections. Expanding the database to incorporate additional technical information and high-quality photomicrographs, and to make it available online, are among the department's active priorities.

Left: Frances Morris, the first woman professional at the Museum, came as a part-time cataloger for musical instruments, then under the purview of the Department of Decorative Arts. She later extended her mandate to textiles and established the first textile study room on the ground floor in 1910. Primarily intended for storage and study of the collection by scholars and designers, it was also a place where textiles were mounted (and possibly restored), as documented in this 1940 photograph of a textile study room situated in the Western European Art Galleries. The woman sewing is identified as “staff person Miss Dickinson.” Right: This photograph was taken in the Museum's new textile conservation facility soon after the department moved there in 1995. Nobuko Kajitani, seated in the front right corner, pioneered an object-centered approach emphasizing microscopic examination of textiles, a focus on manufacturing techniques, and the importance of combining historical sources and scientific data. Today, the department is particularly known for its sophisticated use of advanced imagining techniques for documentation, treatment, and research.

IV. Specialization and Collaboration (1976–2020)

The last quarter of the twentieth century and the first decades of the new millennium have seen further growth in conservation practice at The Met as different specializations attained independent status or upgraded their professional engagement.

The Museum has called on internal and external scientific expertise over the course of its long history. In the 1960s, for example, while searching for means to stabilize the Fuentidueña Apse at The Cloisters, it lent financial support to the research of Seymour Z. Lewin, a chemistry professor at New York University studying the mechanisms of limestone deterioration. Lewin also consulted on the Temple of Dendur, and on Cleopatra's Needle, an Egyptian obelisk situated nearby in Central Park, which William Kuckro had consolidated in 1913 using the same proprietary mixture he later applied to the Museum’s blocks from the tomb of Perneb. In 2003, scientists in the four independent conservation departments joined a newly established Department of Scientific Research and now work in collaboration with all conservation departments and conservators embedded in other departments. Formerly, museum scientists came from universities or industry; in the last thirty years, it has become more common that young scientists enter the field by design, often with prior conservation training. The Network Initiative for Scientific Research (NICS), a pioneer project launched in 2016 and funded through 2022 by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, supports two scientists dedicated to conducting research on works of art in the collections of twelve other New York City museums, in collaboration with conservators and curators from these institutions.

Most of the Museum’s approximately two million works on paper, including rare books, are held in the Department of Drawings and Prints, but they can be found in every curatorial collection. Merritt Safford had proposed a new facility for their care and technical study in 1980, but his vision, somewhat altered, came to fruition only in 2001, when paper and photograph conservation were rehoused in state-of-the-art studios and laboratories. Academic training for photograph conservation dates back only to 1976. Prior to this, the care of photographic materials had traditionally been in the hands of paper specialists. In fact, photographs have always been printed on a variety of substrates, and even those on paper are quite different from drawings and prints in physical structure and chemical makeup. This distinction was acknowledged first in 1990 with the hiring of a photograph conservator and again in 2001 with division of the existing paper and photography laboratory into separate physical and administrative entities. At this time, Photograph Conservation became part of the Department of Photographs—which itself only came into existence in 1992—until it was granted full departmental status in 2015 and also assumed responsibility for the preservation of time-based media. The Department of Paper Conservation continues to be responsible for drawings and prints in all media and techniques, Western illuminated manuscripts on parchment and paper, Indian and Islamic paintings and albums, ivory portrait miniatures, palm-leaf manuscripts, papyrus, paper-based three-dimensional objects, and ephemera.

Responsibility for the Museum's rare books is shared by book, paper, and photograph conservators. Traditionally, fine bookbinders aimed to create presentation volumes that look attractive on the shelf, but this changed at the Museum when master binder and finisher Alfred William Launder (1867–1952) was hired by the Prints Department in 1929. Encouraged by founding curator William Ivins Jr. (1881–1961), among others, Launder invented a new binding structure that allowed books to be opened and read while still preserving their aesthetic and structural integrity. Currently, the care and rehousing of more than one million library books is the responsibility of a conservation team working in the Sherman Fairchild Center for Book Conservation, built in 2011. Unlike most museum conservators who treat works for display or storage, book conservators face a unique challenge: maintaining a collection subject to constant handling by Museum staff and scholarly visitors.

Left: Repair Shop, Print Department, Wing K, Room 104, Basement Floor. 1936. The man on the left doing finishing work is almost certainly Alfred Launder; the finely bound editions on the table are recognizably his work. The man working the press is likely his assistant, Walter Moore. Right: Mindell Dubansky, a trained bookbinder, seen here after she was hired as a restorer in Watson Library in 1983. She later received graduate degrees from the first established book conservation training program in the United States (started in 1981 at Columbia University) and in library science, and is the Museum’s first preservation librarian.

The Costume Institute came into existence in 1946, with the merging of Museum holdings and a private museum of historical and regional costumes; it became a curatorial department in 1959. When the first professional fashion conservators were engaged in the late 1980s, they found the collections in the hands of skilled sewers—women who had worked in the garment industry or the theater—with no understanding of conservation principles. Because fashion is animated by the wearer, it is best understood when displayed in relationship to the human body. Of necessity, costume conservators focus on stabilizing the structure of garments to withstand the stresses thereby incurred and are actively engaged in dressing display mannequins and managing storage. Currently five conservators work in close collaboration with a large team of collections specialists in laboratories and a study/storage facility that opened in 2014 in the Anna Wintour Costume Center.

Left: Only the gentleman, a Mr. Mayer, is mentioned in the Photo Studio logbook entry for this 1941 photograph showing a mannequin being prepared for display in a temporary exhibition. Right: Polaire Weissman Fellow Kaelyn Garcia (left) and conservator Elizabeth Schaeffer check the condition of an ensemble by Tomo Koizumi after it was displayed in the 2019 exhibition Camp: Notes on Fashion.

Using specialized metalworking tools originally owned by Daniel Tachaux that were accessioned in 1912 at the urging of Bashford Dean, the traditional art of making armor was kept alive at the Museum until the early 1970s, by which time Leonard Heinrich and Harvey Murton had retired. Robert Carroll (1946–2000), a skilled restorer and the Museum's first gunsmith, was hired in 1969 and received the honorary title of Armorer in 1976. Conservation professionals joined the department in the early 2000s, completing the transition from armory to workshop to conservation facility with academically trained objects conservators specialized in the treatment of arms and armor. The title of Armorer continues to be held by the ranking conservator.

Armorer Robert Carroll and restorer Joshua Lee in 1996 cleaning a bronze memorial tablet for Bashford Dean before it was installed next to the main entrance to the arms and armor galleries. The tablet, which was unveiled in a private ceremony in the Bashford Dean Memorial Gallery in 1930, was a gift to the Museum from the American sculptor Daniel Chester French, who was also a Trustee. One of French's last works, it was completed by his daughter, the sculptor Margaret French Cresson.

Hermes Knauer, in 2015, cleaning a dagger handle. Knauer was named armorer in 2002. In this position, he deployed his nearly thirty years of experience gained while treating archaeological and historic metalwork in the Department of Objects Conservation.

The Museum began to collect musical instruments during the 1880s and the collection soon grew with gifts from devoted collectors such as Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown (1842–1918). Initially, the instruments were restored by non-specialists, and subsequently, paralleling the arc of development in conservation practices seen elsewhere in the Museum, by skilled and knowledgeable musical instrument makers; since 2008, the collection is cared for by objects conservators with advanced training in the treatment and technical study of musical instruments.

After the departure in 1929 of Frances Morris (1866–1955), who had curated the musical instruments collection for decades, responsibility for their care fell to Joseph Breck (1885–1933), the curator of the Department of Decorative Arts. He had little interest—in his opinion they were "scientific rather than artistic"—and he recommended deaccessioning all but fifteen "artistically important" Western instruments. With this in mind, the renowned musicologist Curt Sachs (1881–1959) was hired in 1939 to "take care" of the collection. His sometimes-radical interventions were carried out in the workshops by woodworkers, painters, and piano technicians.

The instruments did, however, remain in the Museum and the Department of Musical Instruments was established in 1947. Demonstrating to the public how the instruments sounded and were used was important to Emanuel Winternitz (1898–1983), the first curator, who started working with the collection in 1941. Winternitz was a musician in his own right, loved performance, and viewed the collection as part of an aural art form; the focus of restoration carried out at that time was to return the instruments to playable condition. Over the years, this attitude has shifted, and they are now judged to be documents of historic musical instrument making and musical practice of the past as well as devices for making music. Currently, less than two percent of the more than five thousand instruments are occasionally played in concerts at the Museum. Alongside their curatorial counterparts, conservators continue to explore the preservation of sound, which remains an intangible but essential quality of these works.

Left: Emanuel Winternitz in the musical instrument galleries demonstrating a hurdy-gurdy to the Fife and Drum Corps of the Children's Aid Society of Greenwich Village, 1947. Right: Susana Caldeira, the first conservator specialized in the treatment and study of musical instruments to join Objects Conservation, varnishing a replacement batten for a harpsichord in a space devoted to conservation in the Department of Musical Instruments, ca. 2009.

In the early 1970s, the newly established Curatorial Forum, an in-house professional organization, initially voted resoundingly to bar conservators from membership. They were, however, admitted soon afterward, and in concurrence with their expanded professional profile following the reorganization and expansion of the conservation departments a few years later, conservators and conservation scientists became increasingly active in the management of collections, particularly in matters relating to exhibitions, acquisitions and deaccessions, publications, display materials, art-in-transit, emergency preparedness, vibration mitigation, educational programs, and public outreach. They have long taken leadership roles in all activities and initiatives of the Forum for Curators, Conservators, and Scientists, as the organization is now known.

Many of the academically trained conservators who joined the Department of Objects Conservation after 1976 worked at archaeological sites in various locales, and since the early 1990s they have played an important role at the Museum's excavations in Egypt. Both conservators and conservation scientists have increasingly engaged in scholarly collaborations with curators, research associates, fellows, and graduate interns at The Met and elsewhere, and contribute their expertise and skills to conservation and cultural heritage projects around the world.

Left: The Museum resumed field work in Egypt in 1984. By then, partage, the complex arrangement that granted sponsoring institutions a portion of their finds, had been abolished. Since the early 1990s, conservators are essential members of the Museum's team at Dahshur and Lisht. Working with Egyptian colleagues to whom they also provide training, they stabilize standing monuments and other finds that remain on site or are transferred to Egyptian museums for display. Textile conservator Emilia Cortes is seen here in 2007 with team members Ali Hassan Ibrahim and Mohammed Ali Hassan (top). Right: Participants of the second Global Museum Leaders Colloquium, in 2015, while visiting the Department of Photograph Conservation with Nora Kennedy, Sherman Fairchild Conservator in Charge (far right), are shown custom-made housings for different types of three-dimensional photographs in the collection.

V. 2020 and Beyond

In late 2019, the Museum’s first conservator for time-based media joined the Department of Photograph Conservation, reflecting a growing need to preserve vulnerable collections of videos, films, audio tapes, and slide- and software-based artworks. In fact, specialists for modern and contemporary art have joined all of the conservation departments in recent years. Contemporary works of art can offer conservators singular opportunities to engage with living artists as they address problems stemming from the use of unconventional materials, many with unknown aging properties, and the restaging of complex installations of large-scale works comprising hundreds of individual components. Conversely, they sometimes must balance the wishes of these artists or their estates with conventional Museum practices and standards. When installing conceptual art, conservators may find themselves attempting to honor a deceased artist's intentions through written instructions that provide little guidance on materials and structure, just as many living conceptual artists decline to participate in the restaging of their work.

Conservators and conservation scientists working with more traditional materials must continually acquire new skills as new technologies are developed and adapted to conservation practice. The ongoing acquisition of new or updated non- or minimally invasive instrumentation and the skill to operate them and interpret the data augment exponentially our understanding of the Museum's collections. In collaboration with The Met's Imaging Department, Met conservators are experimenting with and implementing a range of new two- and three-dimensional imaging techniques to document, study, and virtually reconstruct works of art. The latter is increasingly important with our growing acknowledgement that reversibility, which is given primacy in modern conservation practice, is often difficult or impossible to attain in practice. New imaging technologies, coupled with 3-D printing techniques, are also beginning to transform mount making for display and travel.

Left: Plaster Cast Shop. L. Schlesinger, in 1937, using a mechanical device to replicate in mirror image the uppermost block of a name panel from Senwosret I’s mortuary temple at Lisht. The plaster replica was used to restore one of the three other fragmentary panels excavated by the Museum over a period of thirty years and later reconstructed in the Egyptian galleries. Right: Working in close collaboration, conservators, conservation preparators, and members of the Imaging Department at The Met used state-of-the-art 3D scanning and milling technologies to safeguard this Chinese dry lacquer image of the Buddha while in transit and on display in a temporary exhibition. Here, seen in 2017, conservation preparator Fred Sager (left) and conservator Daniel Hausdorf are test-fitting newly fabricated elements of a carbon fiber internal support.

The business of running an active museum makes huge demands on the physical environment. One important development in conservation practice over the last several decades is the institution of preventive measures, including climate control. Maintaining appropriate environmental conditions in a building that hosts tens of thousands of visitors each day, however, requires a vast amount of energy. Developing more environmentally sustainable means of regulating interior climates is essential, and conservators and conservation scientists must systematically evaluate current standards, so that any move toward relaxing them is based on sound principles. Conservators are also working to substitute toxic and carcinogenic compounds used in their work with those less damaging to the environment and themselves, and to find practical substitutes for frequently used non-recyclable disposables, such as nitrile gloves, which are used to protect works of art from dirt and damaging oils on human hands and to protect human hands from toxic or caustic substances.

Despite advances over the course of the Museum’s history in the professionalization of conservation practice, conservators and conservation scientists still sometimes struggle with institutional hierarchies that make it difficult for them to promote and maintain established standards for best practice. Working with seventeen curatorial departments, each with unique collections, only adds to the challenge. Along with their unparalleled knowledge of the materials, manufacture, physical history, and artistic intent that have shaped works of art in the Museum's encyclopedic collection, conservation specialists have the expertise to advocate on behalf of their physical well-being. Their input into all activities that can impact these works—which includes planning for Museum construction, gallery installations, temporary exhibitions, in- and outgoing loans, storage environments, and their presentation to the public and professional audiences in print and online publications—is essential. Although the practice of drawing upon this conservation expertise at early stages of every project is sometimes overlooked, conservator specialists at The Met continue to strive to bring their scholarship and collaborative spirit to the forefront for the sake of the collection.

Engagement with indigenous communities that have continuing cultural affiliations with works of art preserved in cultural institutions is increasingly recognized as an essential component of their care. Dialogues with community members can offer valuable knowledge about artworks in the collection, including cultural perspectives and specialized knowledge of traditional media and manufacture. These conversations may also inform preservation and restoration measures and the display and storage of culturally sensitive materials. Conservators are currently surveying the most sensitive of these, human remains, which are represented in virtually every curatorial collection. A working group tasked with drafting a publicly accessible human remains policy for the Museum is considering some of the following issues: how human remains are defined and catalogued, methodologies for appropriate display and storage, best practices for engaging in dialogue with source communities, and protocols for undertaking scientific analysis and conservation treatment. This group includes representation from curatorial and conservation departments and the Counsel’s Office.

Increasing diversity among conservation professionals is a stated priority of the American Institute of Conservation. The traditional racial, ethnic, and class uniformity among their professional staff is inseparable from the challenge faced by museums to make their programs relevant and welcoming to more diverse communities. In recent years, conservators and conservation scientists have participated more actively in Museum educational programs and other outreach initiatives for students in all stages of their education that aim to promote inclusion by fostering broad interest in conservation as a career. The Museum’s conservation departments, working with Education, are exploring opportunities to partner with organizations with existing programs supporting diversity in museums as well as developing their own initiatives. Financial considerations often limit participation in museum internship and fellowship programs and employment to students and professionals with greater monetary resources; in a recent initiative supporting greater diversity among museum professionals, The Met secured a gift that funds a fully paid internship program for undergraduate and graduate students, the largest of its kind in the United States.

Over the course of the Museum's first 150 years, conservation and science research have become established, active sources of specialized expertise, recognized internationally, and a critical component of the Museum's lifeblood. Moving into the future, The Met’s conservation and conservation science staff will continue to work toward achieving ever higher standards for preserving and studying the collection. They will contribute to the advancement of conservation practice around the world through education, outreach, and advocacy, while working with their colleagues in every phase of The Met’s activities to create a more diverse, more inclusive, more sustainable, and more engaged institution, for the benefit of all.