Pair-case watch

The invention of the spiral balance spring by Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) revolutionized the timekeeping properties of a watch in the same way that his application of the pendulum to a clock revolutionized the accuracy of the clock. It was the invention that dismayed the Englishman Robert Hooke (1635–1703) in early 1675,[1] as news of the spiral balance spring undoubtedly helped doom any hope of success of the experimental balance spring in a watch that he and Thomas Tompion (1639–1713) had presented to King Charles II (1630– 1685) of England in May of that same year.[2] Three months earlier, Hooke had begun an extended battle for recognition of the priority of the invention,[3] a battle that was intensified by Huygens’s attempt to register an English patent for the device.[4] Tompion, however, like many of his fellow watchmakers, seemed to have quickly grasped the advantage of Huygens’s balance spring. Jeremy L. Evans, who deciphered Tompion’s earliest efforts at serially numbering his watches, records the existence of only one pre–balance spring watch by Tompion, now missing its dial and cases.[5] The serial number 175 of the Metropolitan Museum’s watch does not appear in the place that would later become usual on the back plate of a watch. Instead, it appears inside, on the pillar plate, leading Evans to propose a date of 1682 or 1683 for this watch.[6] By 1683, Tompion was using the spiral balance spring to make watches that were capable of registering hours, minutes, and seconds, but it was by no means new: on May 17, 1679, Hooke recorded that he had paid Tompion for a “Watch with seconds” destined for Christopher Wren (1632–1723).[7]

The movement is astounding for yet another reason. It contains a remarkably early stop mechanism that can be activated by pushing a lever that projects from under the dial at the forty-three-minute position, to measure short intervals of time. This particular movement consists of two circular plates, held apart by four exquisite tulip pillars, and the movement contains a three-wheel train that is driven by a mainspring and fusee and regulated by a verge escapement and three-armed balance with a balance spring. A large openwork cock with a table of delicate foliate scrolls dominates the back plate, leaving only a small area for the foot of the cock through which the cock is screwed onto the back plate. A quatrefoil, or flower, within a square serves as ornament at the neck of the cock, recalling the ornament of the cock in the Tompion traveling clock watch, also in the Museum’s collection (see entry 23 in this volume). A silver figure plate for adjusting the balance spring and the watchmaker’s signature, “Tho Tompion London” (engraved in script), fill the remaining space on the back plate.[8]

The inner case of plain gold is stamped on the interior with the letters “ND” conjoined, the “D” mostly effaced. Below is the number 175, apparently in keeping with Tompion’s practice of using matching serial numbers for components of his production. Although there is evidence that the finishing of Delander’s cases was sometimes done by specialist craftsmen,[9] the exquisite finish of the matte-gold ground and the finely engraved numerals filled with black wax on the dial of this watch are of a quality reached only by Delander’s establishment, giving credence to the supposition that the “N” of the maker’s mark does indeed stand for Nathaniel. More remarkable still is the design of the dial that records hours in roman numerals and minutes in Arabic numbers on its chapter ring, with separate concentrically mounted and easy-to-read hands for the hours and minutes, while incorporating a large chapter ring for seconds at the six o’clock position of the dial. The seconds chapter would have been necessary for the timing of short periods, perhaps for astronomical events such as an eclipse, or even a sporting event such as a horse race, but its prominence also suggests the watchmaker’s pride in the new level of precision achieved by the movement.

How much of the design of the dial may be attributed to Tompion and how much to Delander is not known, but the evidence provided here and in the case of Tompion’s traveling clock watch suggests that Delander had a special gift. Nothing certain is known of his early life and training, apart from the fact that he was admitted as a Free Brother into the Clockmakers’ Company in London in January 1669, and as a Freeman by payment of a fee in March 1675.[10] There is no agreement about the probable date of his death, but his punched (incuse) “ND” conjoined mark is recorded on the Goldsmiths’ Company’s copperplate that registered maker’s marks in 1682.[11] A second form of mark, which consists of a coronet above the “ND” conjoined and accompanied by a full set of London hallmarks for silver in 1683, appears on a Tompion watch in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, England.[12] It seems likely that Delander had an unusual talent for design as well as for craftsmanship.

The visual logic of the design of this dial seems self-evident; however, in the period following the adoption of Huygens’s balance spring, English watchmakers did not invariably make watches with two hands to indicate hours and minutes on concentric chapter rings. The dial of a pair-case watch of the early 1680s in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection by the London clock- and watchmaker Richard Colston (active 1682–1702)[13] is a good example of an alternative display (17.190.1508). The minutes on Colston’s watch are prominently indicated by a single hand on a chapter ring at the edge of the dial, while the hours appear singly and less easily read through an aperture near the top of the dial, leaving space for decorative cartouches that frame the maker’s name and the place. Yet another aperture for a calendar appears at the bottom of the dial. A number of other alternatives were tried before most eighteenth-century English watchmakers adopted the familiar dial with concentric chapter rings and two hands: one for hours and one for minutes.

The outer case of the Museum’s Tompion watch, with its design in gold nailheads, may also be the work of Delander, although little study has been devoted to the degree of specialization among casemakers during this period, and it may have been the work of another craftsman. The cipher and coronet have long remained unidentified. The precociousness of the design and technical details of this watch so misled George C. Williamson, the author of the catalogue of J. Pierpont Morgan’s watch collection, that he declared it to be a product of the eighteenth century.[14] Subsequent discoveries have proved him mistaken. Williamson asserted that Morgan bought it from Frederick George Hilton Price, who probably bought it from the sale of the collection of Claude Ashley Charles Ponsonby.[15]

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] See Hooke 1968, p. 148, entry of Feb. 18, 1674/75, and p. 153, entry of Mar. 18, 1674/75.

[2] Ibid., p. 161, entry of May 17, 1675. See also entry 23 in this volume.

[3] Ibid., p. 148, entry of Feb. 18, 1674/75. See also Howse and Finch 1976.

[4] Hall 1951; Inwood 2002, pp. 200–215.

[5] J. L. Evans 1984; J. L. Evans 2006, p. 87. See also Thompson 2008, p. 50.

[6] J. L. Evans 2006, p. 87.

[7] Hooke 1968, p. 412. The authors are indebted to Jeremy L. Evans, formerly of the British Museum, London, for bringing this fact to our attention.

[8] For a more detailed description of the movement, see J. L. Evans, Carter, and Wright 2013, pp. 267, 568.

[9] See Thompson 2007, pp. 42–43, no. 19, for a watch with a movement by Thomas Tompion in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (inv. no. WA1974.191.86).

[10] Loomes 1981, p. 190.

[11] Priestley 2000, p. 66, no. 40a.

[12] Ibid., p. 6, fig. 8.

[13] Acc. no. 17.190.1508. See Loomes 1981, p. 160. See also Thompson 2007, pp. 44–45, no. 20, for a Colston watch with a so-called sun and moon dial in the Ashmolean Museum (inv. no. WA1974.116).

[14] Williamson 1912, p. 146, no. 157, and pl. lxx.

[15] Christie’s 1908, p. 3, no. 1. See also J. L. Evans, Carter, and Wright 2013, p. 568. The authors are indebted to Jeremy L. Evans for the latter information.

The movement is astounding for yet another reason. It contains a remarkably early stop mechanism that can be activated by pushing a lever that projects from under the dial at the forty-three-minute position, to measure short intervals of time. This particular movement consists of two circular plates, held apart by four exquisite tulip pillars, and the movement contains a three-wheel train that is driven by a mainspring and fusee and regulated by a verge escapement and three-armed balance with a balance spring. A large openwork cock with a table of delicate foliate scrolls dominates the back plate, leaving only a small area for the foot of the cock through which the cock is screwed onto the back plate. A quatrefoil, or flower, within a square serves as ornament at the neck of the cock, recalling the ornament of the cock in the Tompion traveling clock watch, also in the Museum’s collection (see entry 23 in this volume). A silver figure plate for adjusting the balance spring and the watchmaker’s signature, “Tho Tompion London” (engraved in script), fill the remaining space on the back plate.[8]

The inner case of plain gold is stamped on the interior with the letters “ND” conjoined, the “D” mostly effaced. Below is the number 175, apparently in keeping with Tompion’s practice of using matching serial numbers for components of his production. Although there is evidence that the finishing of Delander’s cases was sometimes done by specialist craftsmen,[9] the exquisite finish of the matte-gold ground and the finely engraved numerals filled with black wax on the dial of this watch are of a quality reached only by Delander’s establishment, giving credence to the supposition that the “N” of the maker’s mark does indeed stand for Nathaniel. More remarkable still is the design of the dial that records hours in roman numerals and minutes in Arabic numbers on its chapter ring, with separate concentrically mounted and easy-to-read hands for the hours and minutes, while incorporating a large chapter ring for seconds at the six o’clock position of the dial. The seconds chapter would have been necessary for the timing of short periods, perhaps for astronomical events such as an eclipse, or even a sporting event such as a horse race, but its prominence also suggests the watchmaker’s pride in the new level of precision achieved by the movement.

How much of the design of the dial may be attributed to Tompion and how much to Delander is not known, but the evidence provided here and in the case of Tompion’s traveling clock watch suggests that Delander had a special gift. Nothing certain is known of his early life and training, apart from the fact that he was admitted as a Free Brother into the Clockmakers’ Company in London in January 1669, and as a Freeman by payment of a fee in March 1675.[10] There is no agreement about the probable date of his death, but his punched (incuse) “ND” conjoined mark is recorded on the Goldsmiths’ Company’s copperplate that registered maker’s marks in 1682.[11] A second form of mark, which consists of a coronet above the “ND” conjoined and accompanied by a full set of London hallmarks for silver in 1683, appears on a Tompion watch in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, England.[12] It seems likely that Delander had an unusual talent for design as well as for craftsmanship.

The visual logic of the design of this dial seems self-evident; however, in the period following the adoption of Huygens’s balance spring, English watchmakers did not invariably make watches with two hands to indicate hours and minutes on concentric chapter rings. The dial of a pair-case watch of the early 1680s in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection by the London clock- and watchmaker Richard Colston (active 1682–1702)[13] is a good example of an alternative display (17.190.1508). The minutes on Colston’s watch are prominently indicated by a single hand on a chapter ring at the edge of the dial, while the hours appear singly and less easily read through an aperture near the top of the dial, leaving space for decorative cartouches that frame the maker’s name and the place. Yet another aperture for a calendar appears at the bottom of the dial. A number of other alternatives were tried before most eighteenth-century English watchmakers adopted the familiar dial with concentric chapter rings and two hands: one for hours and one for minutes.

The outer case of the Museum’s Tompion watch, with its design in gold nailheads, may also be the work of Delander, although little study has been devoted to the degree of specialization among casemakers during this period, and it may have been the work of another craftsman. The cipher and coronet have long remained unidentified. The precociousness of the design and technical details of this watch so misled George C. Williamson, the author of the catalogue of J. Pierpont Morgan’s watch collection, that he declared it to be a product of the eighteenth century.[14] Subsequent discoveries have proved him mistaken. Williamson asserted that Morgan bought it from Frederick George Hilton Price, who probably bought it from the sale of the collection of Claude Ashley Charles Ponsonby.[15]

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] See Hooke 1968, p. 148, entry of Feb. 18, 1674/75, and p. 153, entry of Mar. 18, 1674/75.

[2] Ibid., p. 161, entry of May 17, 1675. See also entry 23 in this volume.

[3] Ibid., p. 148, entry of Feb. 18, 1674/75. See also Howse and Finch 1976.

[4] Hall 1951; Inwood 2002, pp. 200–215.

[5] J. L. Evans 1984; J. L. Evans 2006, p. 87. See also Thompson 2008, p. 50.

[6] J. L. Evans 2006, p. 87.

[7] Hooke 1968, p. 412. The authors are indebted to Jeremy L. Evans, formerly of the British Museum, London, for bringing this fact to our attention.

[8] For a more detailed description of the movement, see J. L. Evans, Carter, and Wright 2013, pp. 267, 568.

[9] See Thompson 2007, pp. 42–43, no. 19, for a watch with a movement by Thomas Tompion in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (inv. no. WA1974.191.86).

[10] Loomes 1981, p. 190.

[11] Priestley 2000, p. 66, no. 40a.

[12] Ibid., p. 6, fig. 8.

[13] Acc. no. 17.190.1508. See Loomes 1981, p. 160. See also Thompson 2007, pp. 44–45, no. 20, for a Colston watch with a so-called sun and moon dial in the Ashmolean Museum (inv. no. WA1974.116).

[14] Williamson 1912, p. 146, no. 157, and pl. lxx.

[15] Christie’s 1908, p. 3, no. 1. See also J. L. Evans, Carter, and Wright 2013, p. 568. The authors are indebted to Jeremy L. Evans for the latter information.

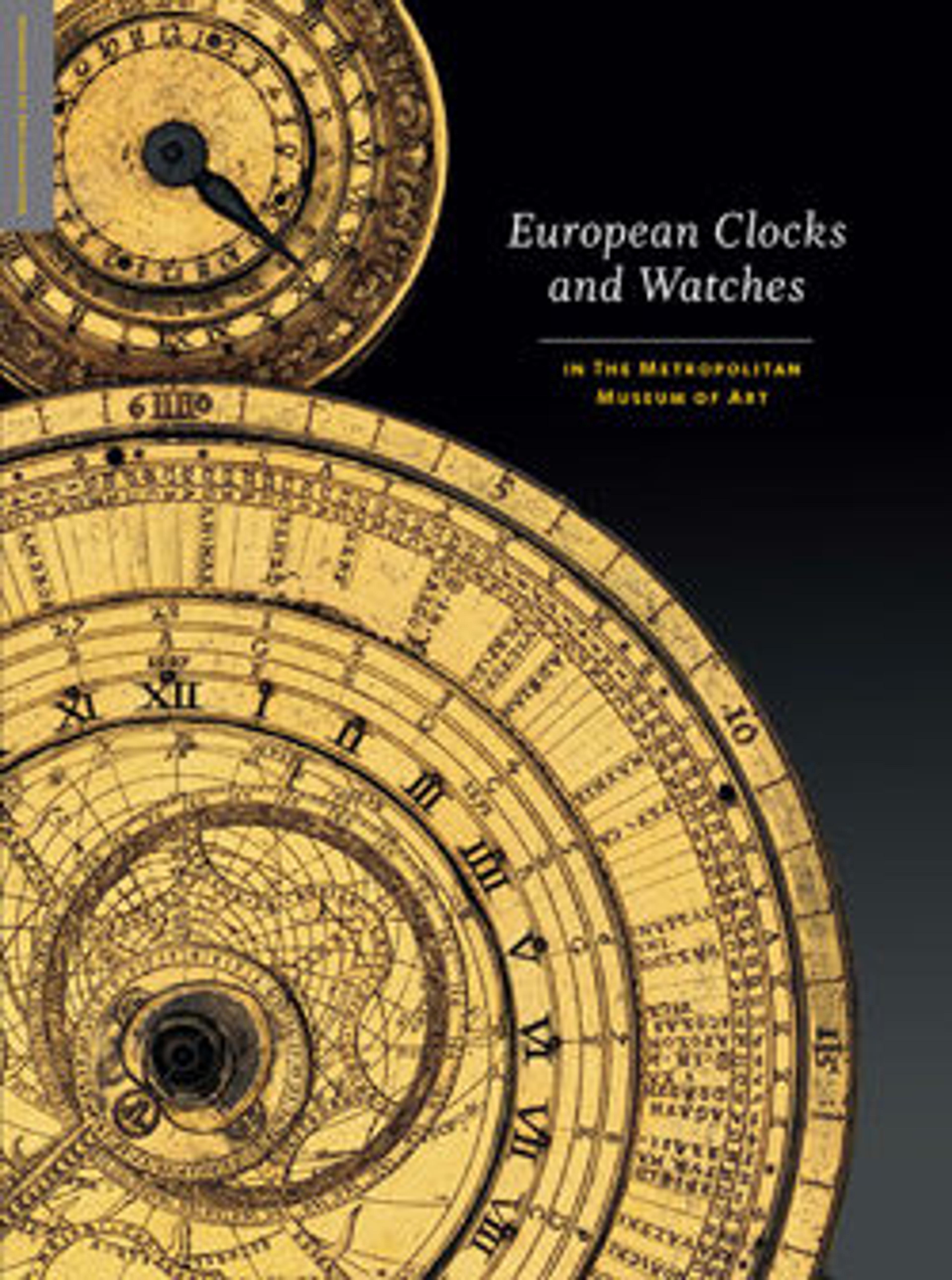

Artwork Details

- Title: Pair-case watch

- Maker: Watchmaker: Thomas Tompion (British, 1639–1713)

- Maker: Case maker: Nathanial Delander I (British, 1648–ca. 1691)

- Date: 1682–83

- Culture: British, London

- Medium: Outer case: leather with gold studs; inner case and dial: gold with blued-steel hands; movement: gilded brass, partly blued steel, silver

- Dimensions: Diameter (outer case): 2 1/16 in. (5.2 cm)

Diameter (inner case): 1 3/4 in. (4.4 cm)

Diameter (back plate): 1 7/16 in. (3.7 cm) - Classification: Horology

- Credit Line: Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917

- Object Number: 17.190.1489a, b

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.