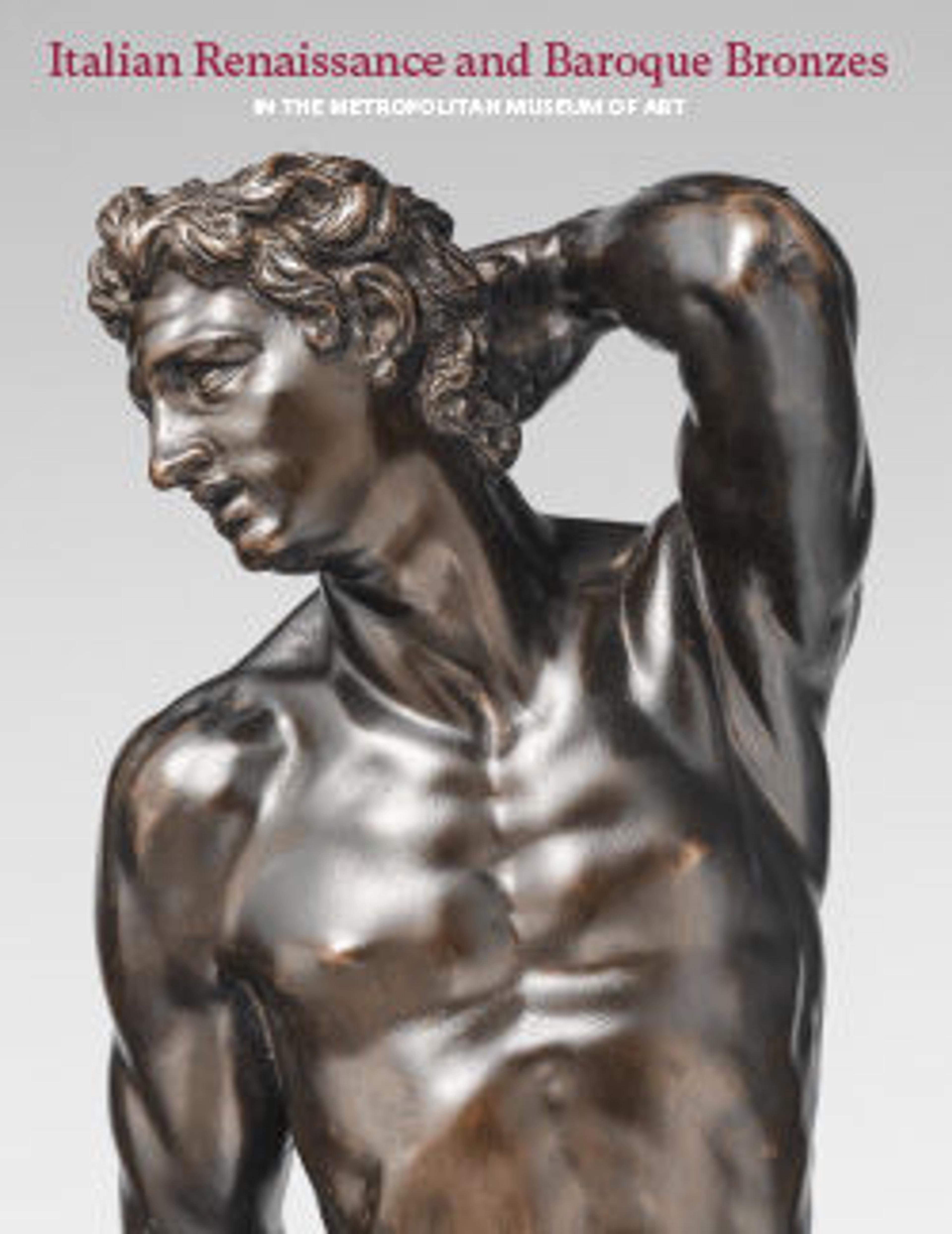

Head of a Child with Hair

Ogden Mills acquired these two small busts at the sale of the Henri Lehmann collection in 1925, along with nearly twenty other bronzes, all given to The Met that same year. As Mills explained to curator Joseph Breck, “During the past season in Paris there were two very good collections of 16th Century Italian Bronzes sold. This is the first time for a considerable number of years since any such objects came upon the market. I have purchased the more important bronzes in both collections, especially the Lehmen [sic] collection.”[1]

The Head of an Infant is a low-quality cast likely dating to the nineteenth century with several features intended to evoke similar ancient busts of children. The artificial lacquering mimics a natural burial patina, with a thin black layer resting on a thick layer of purplish red opaque paint meant to imitate cuprite.[2] A square indentation on the proper left cheek has been cast into the head, a self-conscious fashioning on the sculptor’s part to simulate antique damage. Scraping around the eyes represents a feeble attempt to replicate traces of gilding. The head bears a superficial similarity to other Renaissance statuettes, but its material characteristics support a much later dating.[3]

Paired with the Head of an Infant even before entering Mills’s collection, the Head of a Child with Hair may be an after-cast of an unknown Renaissance model. The hairstyle and facial features are related to the physiognomies of children by Andrea Mantegna, placing the prototype in northern Italy around 1500.[4] Our bronze, however, displays many casting defects, blurriness in the articulation of the curls, and an overall worn surface with a thin black patina. Indications of a mold seam on the left side of the head and neck point to its origin as an after-cast. The eyes were scraped clean of patina, as in the other bust, giving an impoverished idea of gilding. The right shoulder is somewhat misshapen, perhaps the result of a heavy blow. Emerging from a distinguished French private collection, this pair of busts epitomizes the challenges faced by early collectors of bronzes in navigating issues of quality, origin, and dating.

-JF

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Letter from Mills to Breck, dated July 23, 1925, MMA Archives.

2. R. Stone/TR April 10, 2008.

3. See, for example, the bust of a child in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, KK 5591; Planiscig 1930, no. 208. A similar head was once in the Dreyfus collection and had a hole in the top.

4. Another example, superior to ours in casting, is in the Wallace Collection, S63. Both are related to the analogous marble head of a child in the Estensische Kunstsammlung, Vienna; see Planiscig 1921, p. 343, figs. 355, 356.

The Head of an Infant is a low-quality cast likely dating to the nineteenth century with several features intended to evoke similar ancient busts of children. The artificial lacquering mimics a natural burial patina, with a thin black layer resting on a thick layer of purplish red opaque paint meant to imitate cuprite.[2] A square indentation on the proper left cheek has been cast into the head, a self-conscious fashioning on the sculptor’s part to simulate antique damage. Scraping around the eyes represents a feeble attempt to replicate traces of gilding. The head bears a superficial similarity to other Renaissance statuettes, but its material characteristics support a much later dating.[3]

Paired with the Head of an Infant even before entering Mills’s collection, the Head of a Child with Hair may be an after-cast of an unknown Renaissance model. The hairstyle and facial features are related to the physiognomies of children by Andrea Mantegna, placing the prototype in northern Italy around 1500.[4] Our bronze, however, displays many casting defects, blurriness in the articulation of the curls, and an overall worn surface with a thin black patina. Indications of a mold seam on the left side of the head and neck point to its origin as an after-cast. The eyes were scraped clean of patina, as in the other bust, giving an impoverished idea of gilding. The right shoulder is somewhat misshapen, perhaps the result of a heavy blow. Emerging from a distinguished French private collection, this pair of busts epitomizes the challenges faced by early collectors of bronzes in navigating issues of quality, origin, and dating.

-JF

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Letter from Mills to Breck, dated July 23, 1925, MMA Archives.

2. R. Stone/TR April 10, 2008.

3. See, for example, the bust of a child in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, KK 5591; Planiscig 1930, no. 208. A similar head was once in the Dreyfus collection and had a hole in the top.

4. Another example, superior to ours in casting, is in the Wallace Collection, S63. Both are related to the analogous marble head of a child in the Estensische Kunstsammlung, Vienna; see Planiscig 1921, p. 343, figs. 355, 356.

Artwork Details

- Title: Head of a Child with Hair

- Date: after an early 16th-century model

- Culture: Northern Italian

- Medium: Bronze, eyes polished

- Dimensions: Overall with bolt: 4 1/2 × 3 × 3 1/2 in. (11.4 × 7.6 × 8.9 cm)

- Classification: Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line: Gift of Ogden Mills, 1925

- Object Number: 25.142.17

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.