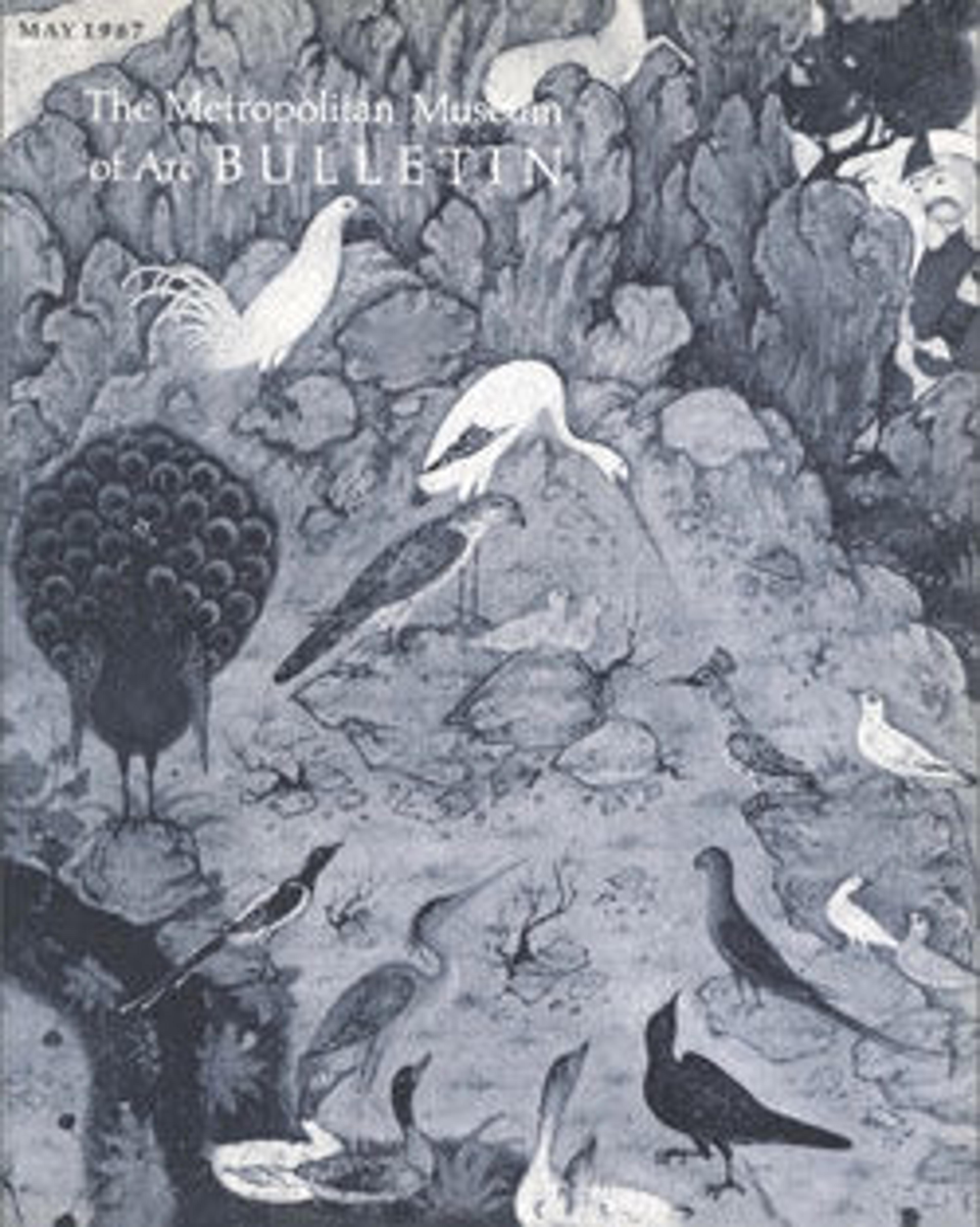

"A Ruffian Spares the Life of a Poor Man", Folio 4v from a Mantiq al-Tayr (Language of the Birds)

This painting once formed part of a rare surviving illustrated copy of Farid al-Din 'Attar’s mystical poem, the Mantiq al-tair (Language of the Birds). Originally commissioned in the late fifteenth century, the manuscript was left unfinished, completed over a century later during the reign of the Safavid ruler Shah 'Abbas I (r. 1587–1629). Four new paintings were added at that time, including this seventeenth century illustration for the story of a ruffian who spares the life of a poor man.

Artwork Details

- Title: "A Ruffian Spares the Life of a Poor Man", Folio 4v from a Mantiq al-Tayr (Language of the Birds)

- Author: Farid al-Din `Attar (Iranian, Nishapur ca. 1142–ca. 1220 Nishapur)

- Date: ca. 1600

- Geography: Made in Iran, Isfahan

- Medium: Ink, opaque watercolor, silver, and gold on paper

- Dimensions: Painting: H. 7 3/4 in. (19.7 cm)

W. 4 1/2 in. (11.4 cm)

Page: H. 12 7/8 in. (32.7 cm)

W. 8 5/16 in. (21.1 cm)

Mat: H. 19 1/4 in. (48.9 cm)

W. 14 1/4 in. (36.2 cm) - Classification: Codices

- Credit Line: Fletcher Fund, 1963

- Object Number: 63.210.4

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.