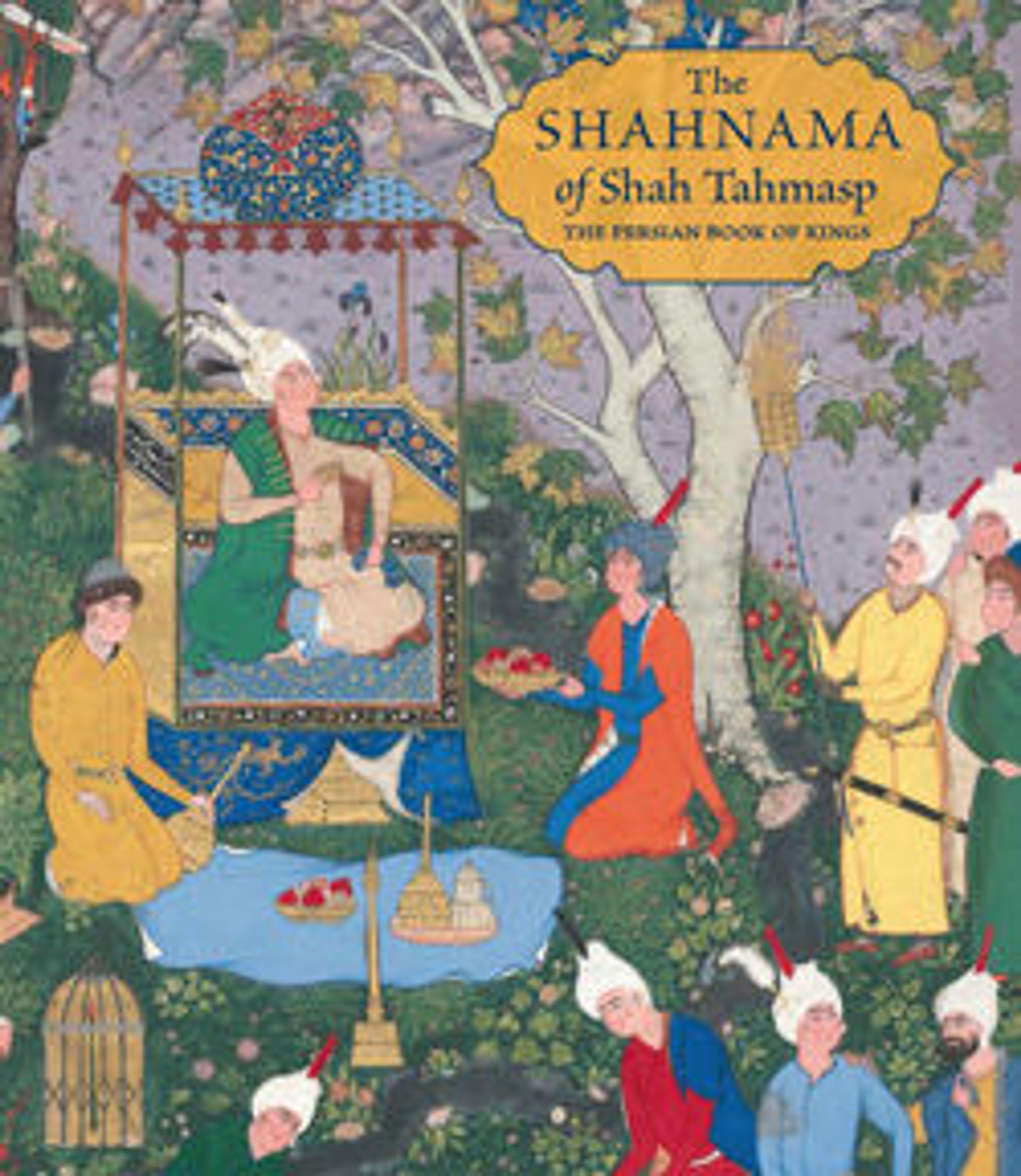

"The Besotted Iranian Camp Attacked by Night", Folio 241r from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp

Following a rout at the hands of the Iranians, the army of Turan regrouped and planned its attack. Before the battle could begin, the Turanians learned that the whole Iranian army was in its cups, drunkenly celebrating its victory. Taking the Iranians by surprise, the Turanians attacked their encampment, slaughtering the besotted soldiers as the few survivors fled in disarray. The artist Qadimi has captured the chaos of the melee with Iranians trapped amidst tents and terrified horses as the Turanians attack them with swords, daggers, and spears.

Artwork Details

- Title: "The Besotted Iranian Camp Attacked by Night", Folio 241r from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp

- Author: Abu'l Qasim Firdausi (Iranian, Paj ca. 940/41–1020 Tus)

- Artist: Painting attributed to Qadimi (Iranian, active ca. 1525–1565)

- Date: ca. 1525–30

- Geography: Made in Iran, Tabriz

- Medium: Opaque watercolor, ink, silver, and gold on paper

- Dimensions: Painting:

H. 11 1/8 in. (28.2 cm)

W. 9 1/8 in. (23.2 cm)

Entire Page:

H. 18 11/16 in. (47.5 cm)

W. 12 5/8 in. (32.1 cm) - Classification: Codices

- Credit Line: Gift of Arthur A. Houghton Jr., 1970

- Object Number: 1970.301.36

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.