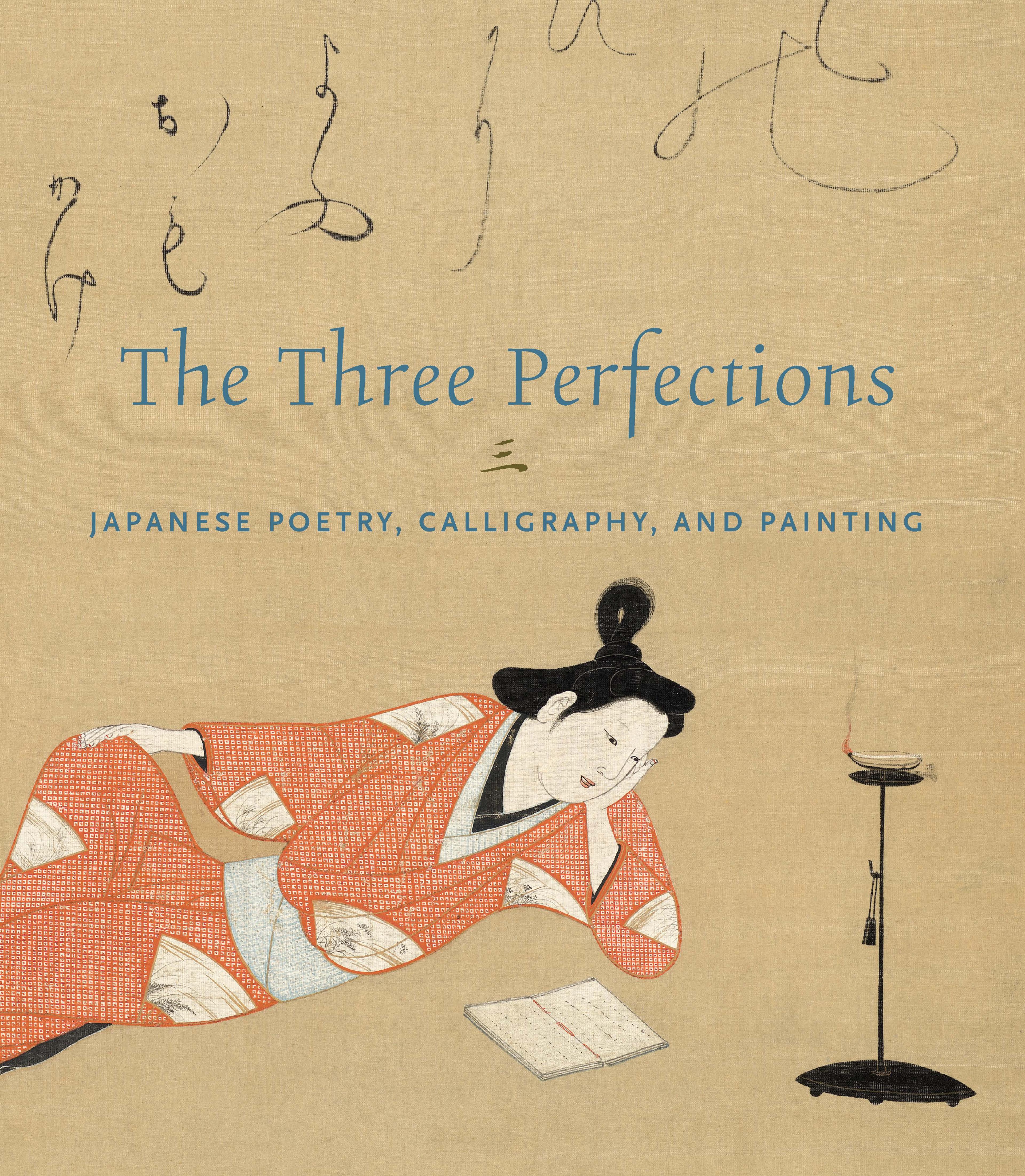

Two Sample Letters on the Chinese Lantern Festival and a Poem about Plum Blossoms

This handscroll by the Kyoto calligrapher Kojima Sōshin begins with passages from letter templates ushering in the Lantern Festival, which marked the end of the New Year’s celebrations on the fifteenth day of the first month. The scroll concludes with a Chinese poem about plum blossoms. Sōshin’s blending of bold and thin characters, on lavishly decorated paper, creates a sense of festivity.

Artwork Details

- 小島宗貞筆 「元宵」尺牘二首・「梅」七言絶句一首

- Title: Two Sample Letters on the Chinese Lantern Festival and a Poem about Plum Blossoms

- Artist: Calligraphy by Kojima Sōshin (Japanese, 1580–ca. 1656)

- Period: Edo period (1615–1868)

- Date: 1657

- Culture: Japan

- Medium: Handscroll: ink on decorated paper

- Dimensions: Image: 10 7/8 in. × 13 ft. 5/16 in. (27.6 × 397 cm)

Overall with mounting: 10 7/8 in. × 13 ft. 11 11/16 in. (27.6 × 426 cm)

Overall with knobs: 11 1/2 in. × 13 ft. 11 11/16 in. (29.2 × 426 cm) - Classification: Calligraphy

- Credit Line: Mary and Cheney Cowles Collection, Gift of Mary and Cheney Cowles, 2020

- Object Number: 2020.396.21

- Curatorial Department: Asian Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.