Phrase about the female deity Mazu

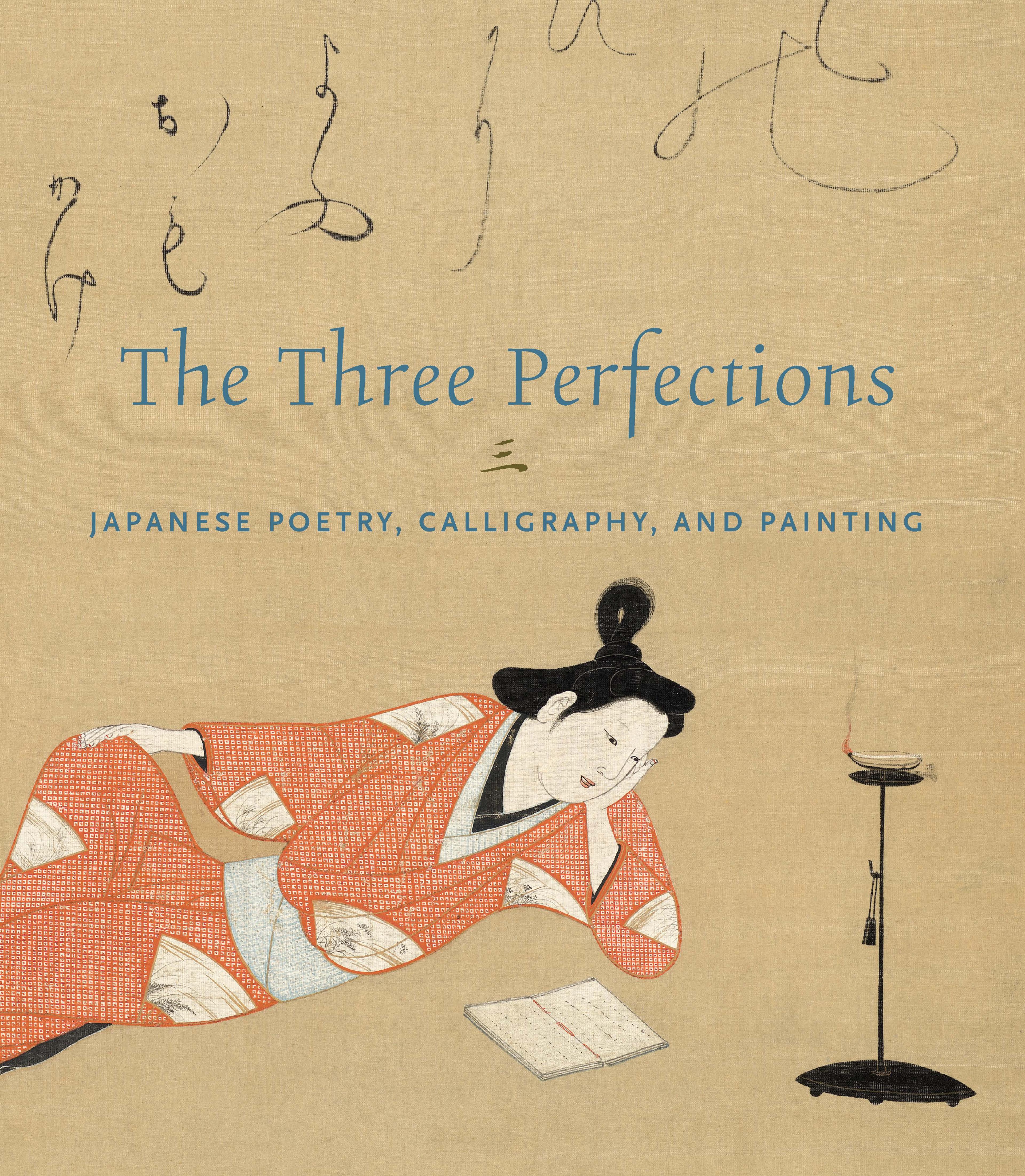

This exuberantly brushed calligraphy embodies the energy of the cursive script of Jifei Ruyi, one of the three celebrated Ōbaku masters of calligraphy (Ōbaku no sanpitsu). It represents a combination of firm control and swift execution, as evidenced by the lingering presence of “flying white,” where a somewhat dry brush splits so the strokes show individual hairs. Even with the brisk motion of the brush, the characters maintain legibility in a well-structured layout, achieving a uniform and bold thickness throughout the composition. The result is a written phrase with a strong visual presence.

慈愛見婆心

The nurturing love of the heart

of an elderly woman [Mazu] is revealed.

Trans. by Tim T. Zhang

This calligraphy describes the compassion of a specific deity: Mazu is a maritime goddess whose cult originated in Fujian during the Song dynasty. She has been revered as a manifestation of Kannon, the bodhisattva of infinite compassion, as well as a guardian of sailors and fishermen. Her worship later spread along China’s coasts and communities in East and Southeast Asia, reaching Japan during the Edo period. It also appears on the left panel of a pair of carved wooden plaques that adorn the entrance of a hall dedicated to the worship of Mazu in Sōfukuji, one of the first temples established through the patronage of Chinese maritime merchants in Nagasaki. Further research is required to determine whether this scroll served as the model for the carved panel or whether it is a subsequent version.

慈愛見婆心

The nurturing love of the heart

of an elderly woman [Mazu] is revealed.

Trans. by Tim T. Zhang

This calligraphy describes the compassion of a specific deity: Mazu is a maritime goddess whose cult originated in Fujian during the Song dynasty. She has been revered as a manifestation of Kannon, the bodhisattva of infinite compassion, as well as a guardian of sailors and fishermen. Her worship later spread along China’s coasts and communities in East and Southeast Asia, reaching Japan during the Edo period. It also appears on the left panel of a pair of carved wooden plaques that adorn the entrance of a hall dedicated to the worship of Mazu in Sōfukuji, one of the first temples established through the patronage of Chinese maritime merchants in Nagasaki. Further research is required to determine whether this scroll served as the model for the carved panel or whether it is a subsequent version.

Artwork Details

- 即非如一筆 一行書「慈愛見婆心」

- Title: Phrase about the female deity Mazu

- Artist: Jifei Ruyi (Sokuhi Nyoitsu) (Chinese, 1616–1671)

- Date: ca. 1665–71

- Culture: Japan

- Medium: Hanging scroll; ink on paper

- Dimensions: Image: 47 13/16 × 13 7/8 in. (121.4 × 35.3 cm)

Overall with mounting: 77 9/16 × 23 3/8 in. (197 × 59.3 cm) - Classification: Calligraphy

- Credit Line: Mary and Cheney Cowles Collection, Gift of Mary and Cheney Cowles, 2024

- Object Number: 2024.412.10

- Curatorial Department: Asian Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.