The Met's two monographic exhibitions of Eugène Delacroix—Devotion to Drawing: The Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugène Delacroix (on view through November 12) and Delacroix (on view through January 9)—offer a comprehensive view of the artist's work, from large-scale painting to intimate drawings and an array of prints and illustrations. Most of the prints on view in these shows are drawn from the Museum's own collection, which encompasses a broad range of Delacroix's work in lithography, etching, and aquatint. Printmaking formed an integral part of Delacroix's practice from the very beginning of his career: indeed, at the tender age of sixteen he etched a small plate of caricatural sketches, and not long after, his satirical prints were the earliest works by the artist to enter the public sphere.

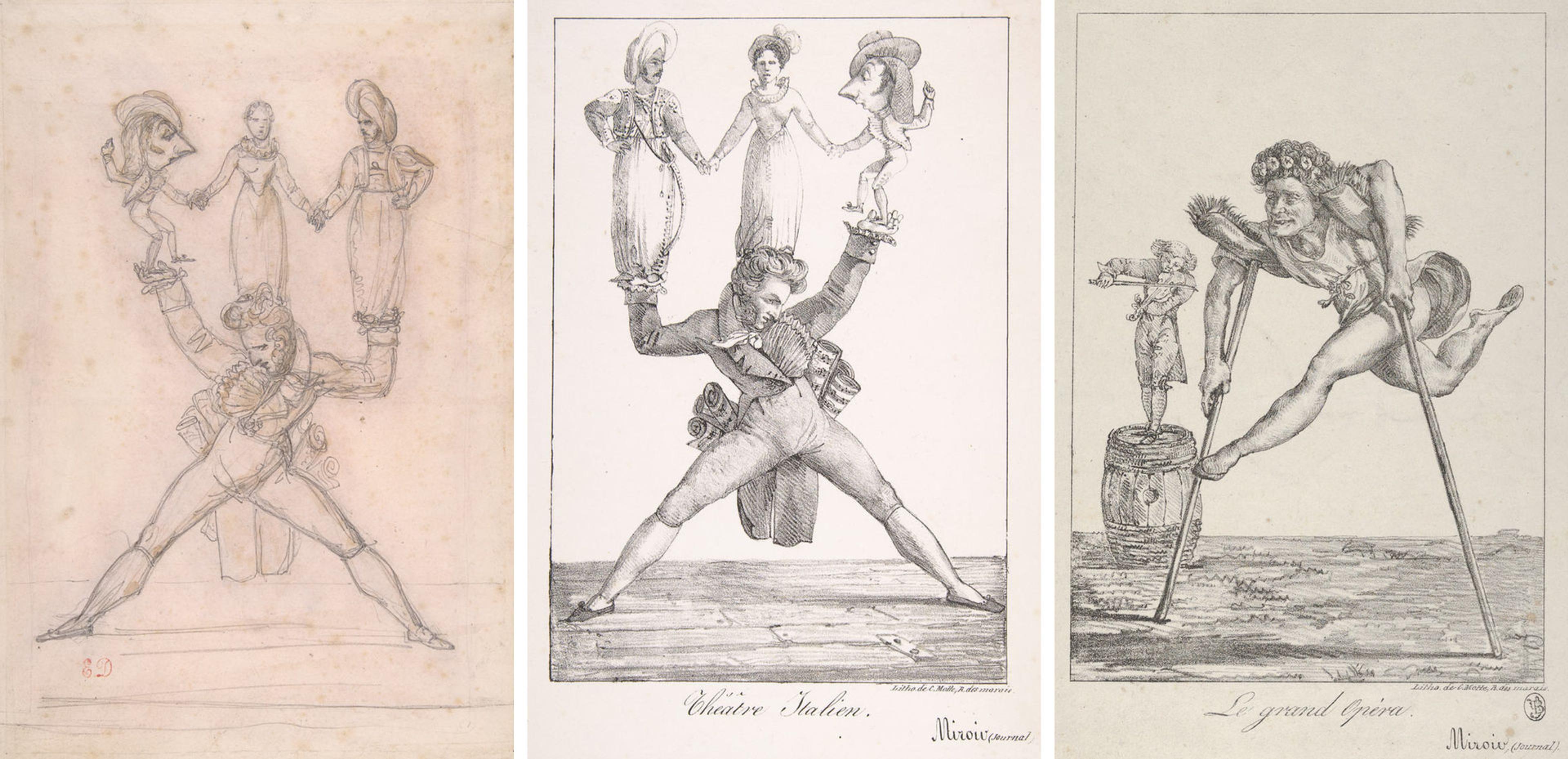

Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863). Left: Théâtre Italien (Gioacchino Rossini, 1792–1868), 1821. Graphite with brush and brown wash; red chalk applied to verso for image transfer, sheet: 10 1/2 x 7 1/2 in. (26.6 x 19 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Karen B. Cohen Gift, 2004 (2004.197). Center: Théâtre Italien, 1821. Printed by Charles Motte (French, 1785–1836). Lithograph; only state, sheet: 10 1/16 x 7 5/16 in. (25.6 x 18.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Karen B. Cohen Gift, 2004 (2004.198). Right: Le Grand Opéra, 1821. Lithograph; second state of two, sheet: 10 13/16 x 8 9/16 in. (27.5 x 21.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1928 (28.80.4)

Devotion to Drawing includes a drawing preparatory to a lithographic caricature of the Théâtre Italien alongside the print and its pendant, which when seen together aid the viewer in understanding the nature of the artist's critique. Published in the new liberal daily Le Miroir as counterparts, the prints pit two Parisian theatrical institutions against one another. Delacroix holds up the Théâtre Italien—embodied here by the famed opera composer Gioacchino Rossini—as an admirable exemplar of the modern. Fashionably dressed, his pockets stuffed with scores, Rossini adopts a robust, wide-legged stance as he balances his three best-known characters: Figaro, Rosina, and Othello. In contrast, Le Grand Opéra portrays an aging former star in a classical tunic, hobbling along on broomstick-crutches; his infirmity suggests the institution's decline. Collectively, these prints demonstrate Delacroix's early and explicit objection to the dominance of the Neoclassical aesthetic across the arts.

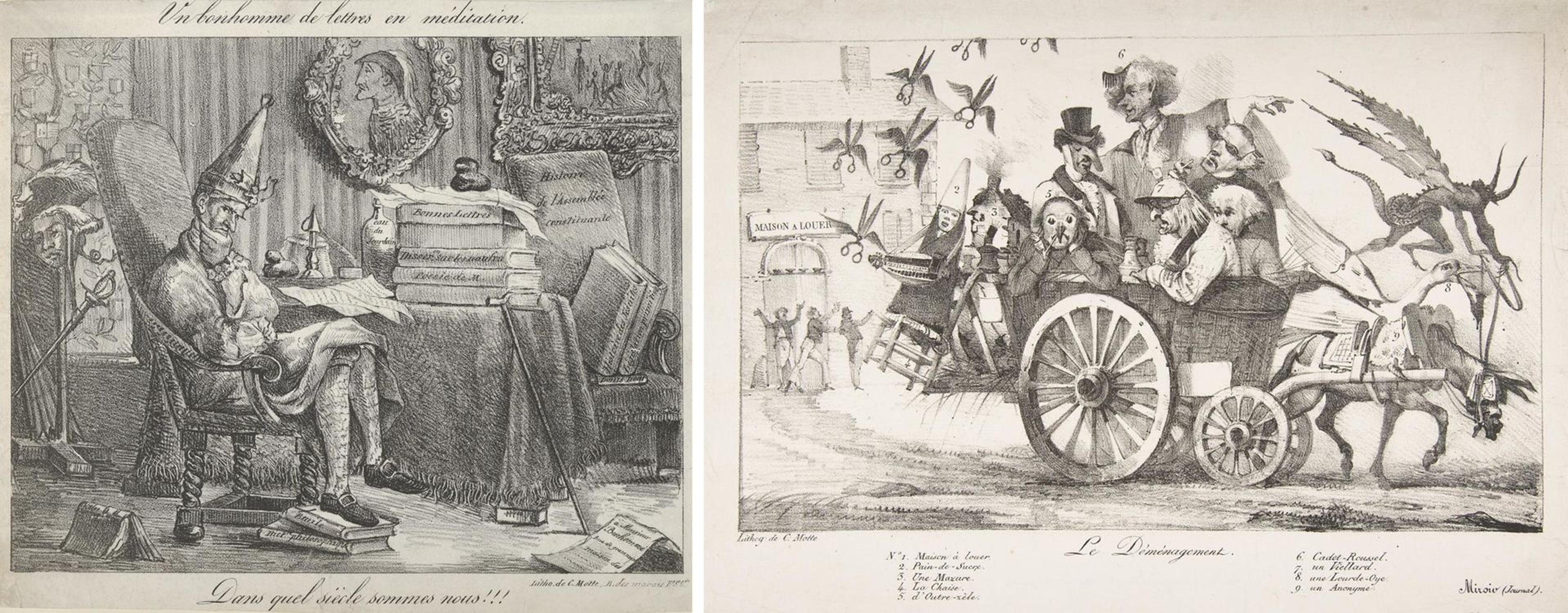

Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863). Left: A Literary Fellow Meditating, 1821. Lithograph; second state of three, sheet: 12 1/8 x 8 7/8 in. (30.8 x 22.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1956 (56.567.50). Right: The Board of Censors Moves Out, 1822. Printed by Charles Motte (French, 1785–1836). Lithograph; only state, sheet: 10 x 13 9/16 in. (25.4 x 34.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1949 (49.21.105)

The Met collection contains seven of the eight lithographs Delacroix contributed to Le Miroir. A Literary Fellow Meditating addresses a similar theme to the previous pair. It mocks the figure of the old Academician, insulated from the outside world in his study with the curtains drawn and surrounded by symbols of his reactionary thinking. The caption below asks: "In what century are we?!!"

The Board of Censors Moves Out reacts to one of the frequent changes to France's censorship laws during this period. Published in February 1822, shortly after censorship was ostensibly abolished, Delacroix depicts a cartload of censors leaving behind their headquarters—their caravan steered by a flying devil, and the instruments of their censorship, the winged scissors, taking flight in their wake. In the French-language edition of the Delacroix catalogue, Segolène Le Men points out that Delacroix's work in caricature introduced him to "conventions of an art more expressive than mimetic."[1] These early prints, from both an ideological and aesthetic point of view, continue to resonate throughout the remainder of his career.

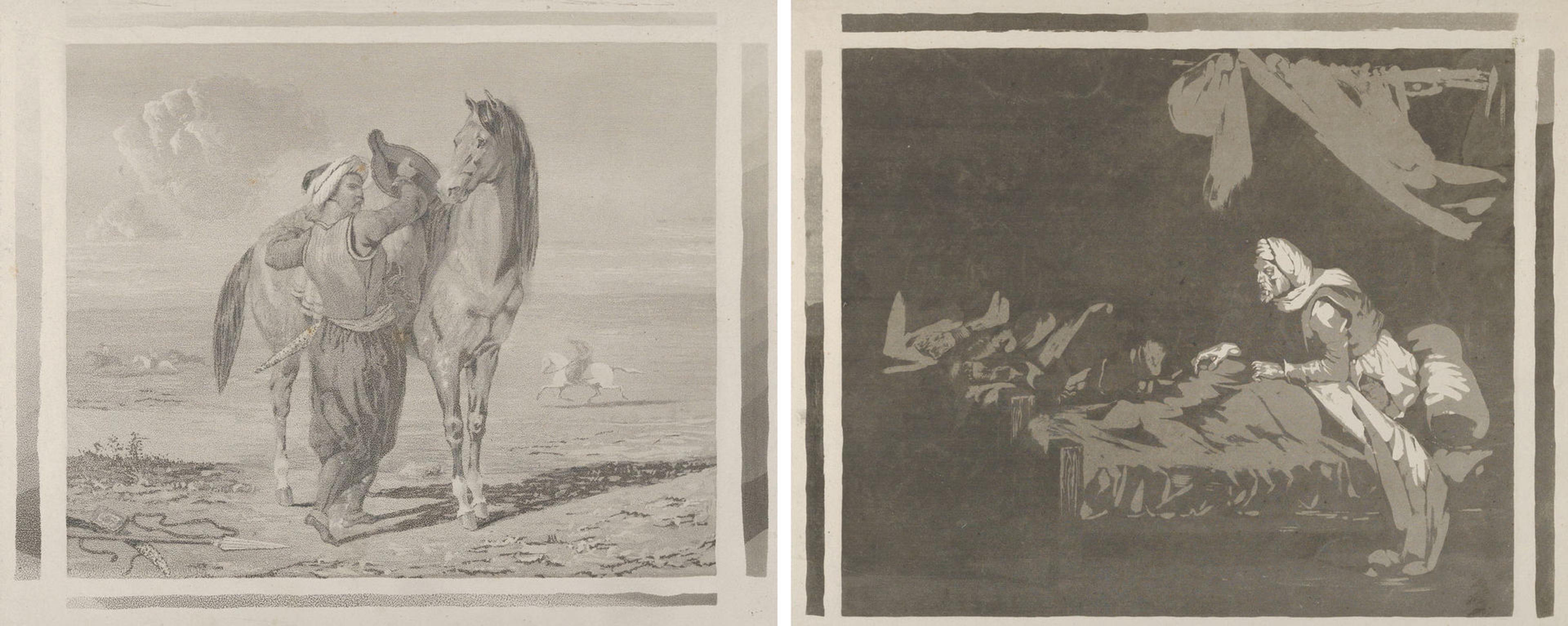

Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863). Left: A Turk Saddling His Horse, 1824. Aquatint with additions in graphite, sheet: 13 3/8 x 9 13/16 in. (33.9 x 25 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Derald H. Ruttenberg Gift, 1998 (1998.529). Right: Interior of a Military Hospital, 1828 or earlier. Aquatint, sheet: 13 5/16 x 10 7/8 in. (33.8 x 27.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1922 (22.63.13)

Delacroix was a true painter-printmaker, one who did not just try his hand at the new medium of lithography, but also worked in etching and aquatint. The Museum's collection holds four out of the five aquatints made by the artist. Two masterful examples of his use of the tonal technique are included in the retrospective: A Blacksmith and Turk Mounting His Horse. The collector's mark on the latter and those on two other aquatints (not currently on view) are a testament to some of the prominent early collectors of Delacroix's prints: A Turk Saddling His Horse was in the collection of Alexis Rouart (1839–1911), an industrialist and member of a collecting family, who assembled a distinguished collection of Romantic art. Interior of a Military Hospital was in the collection of Philippe Burty (1830–1890), the critic and collector who, in the year before Delacroix's death, corresponded with the artist about publishing a catalogue raisonné of his prints.

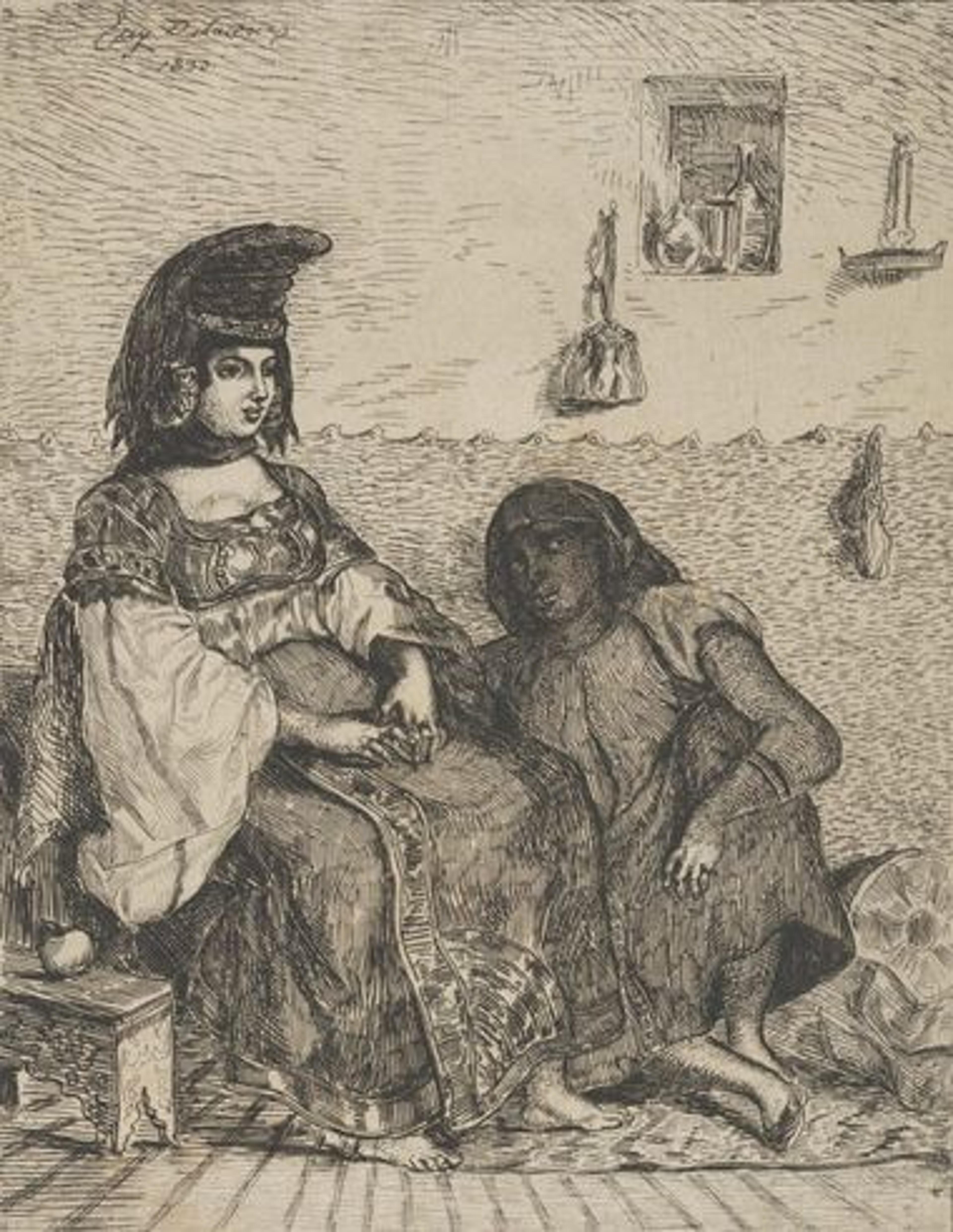

Left: Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863). A Jewish Bride in Tangier, 1833. Etching; first state of four, sheet: 10 1/8 x 7 5/16 in. (25.7 x 18.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Jacob H. Schiff Bequest, 1922 (22.60.14)

Another print from Burty's collection now held at The Met is the etching A Jewish Bride in Tangier. Delacroix took renewed interest in etching thanks to his friendship with Frédéric Villot, a printmaker specialized in interpretive or reproductive etchings. In 1833, Delacroix etched an affectionate portrait of Villot's wife, Pauline. Around this time, he prepared six etchings and a small frontispiece. Villot printed proofs from the plates (The Met's impression of Jewish Bride is one), but the series was not published during the artist's lifetime. Later, the leading publisher for the etching revival, Alfred Cadart, acquired the plates from Villot's 1865 sale and published them in multiple editions. Delacroix made a few later etchings after this 1833 spurt, but it is safe to say his most sustained endeavors in printmaking were in lithography; he made 28 etchings compared to 109 lithographs.

Most of the masterpieces among Delacroix's lithographic oeuvre are on view in Delacroix, including Baron Schwiter, Royal Tiger, Lion of the Atlas Mountains, Wild Horse, and Wild Horse Felled by a Tiger. Though too numerous to discuss all in great detail here, a couple deserve particular note. Macbeth Consulting the Witches is the artist's first print of a Shakespearean subject—in fact, his first of a literary subject. It stands out in Delacroix's oeuvre for being executed almost entirely in a reductive technique, in which the artist used a scraper to create the white lines. Many of his subsequent lithographs incorporate this approach.

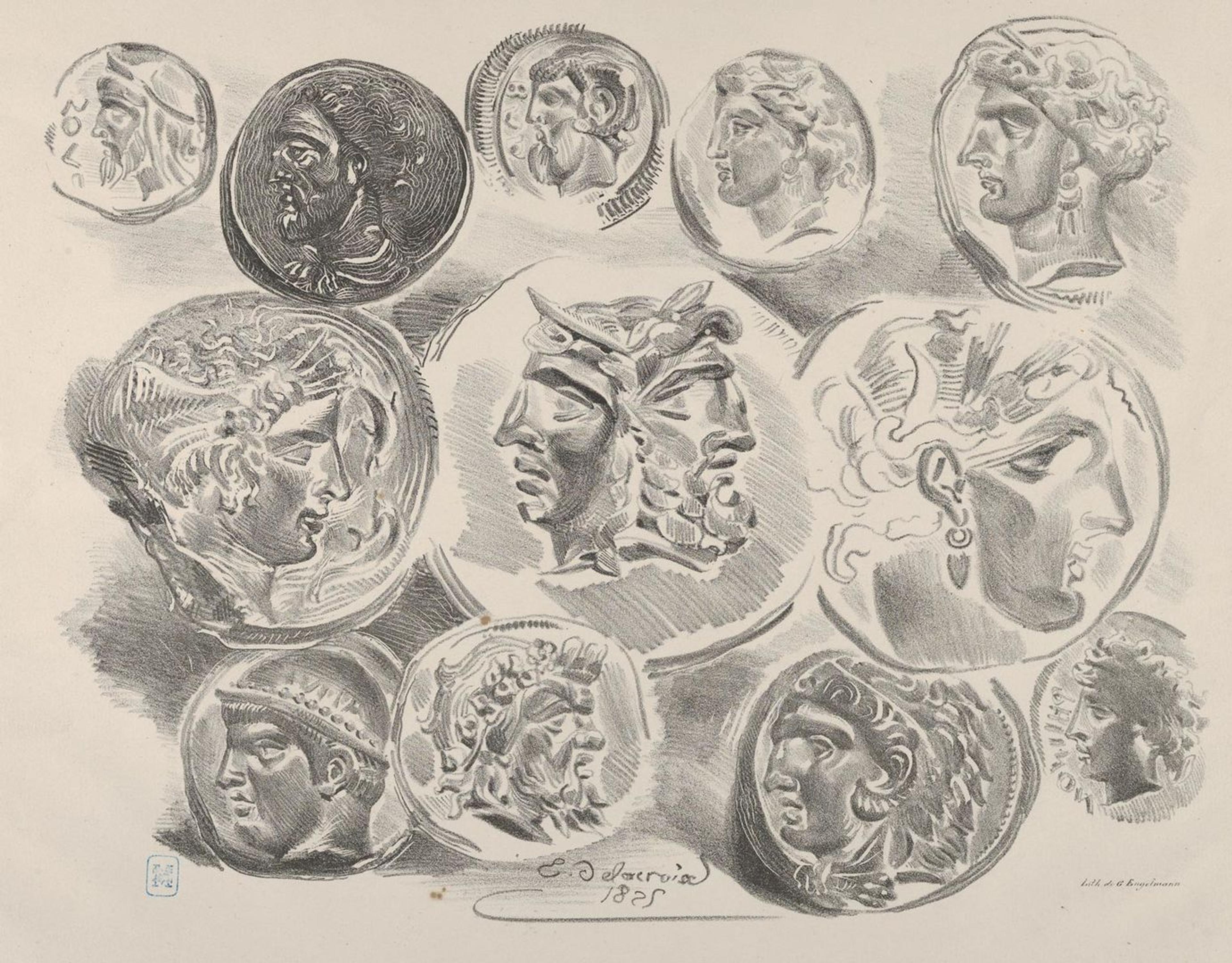

Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863). Studies of Twelve Greek and Roman Coins, 1825. Lithograph; second state of four, sheet: 11 5/8 x 15 7/16 in. (29.6 x 39.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1931 (31.77.24)

Delacroix's five lithographs of antique coins form another seminal set of works; two impressions from this group feature in the retrospective. Printed by Godefroy Engelmann, the prints belonged to Adolphe Moreau, the author of Delacroix's first catalogue raisonné. The lithographic stones were later sold in Delacroix's estate sale and reprinted posthumously in the journal L'Artiste. The other impressions in the Museum's collection come from the later printing. Critic and art historian Théophile Silvestre described these coin studies as "the foundation of [Delacroix's] drawing system." Rather than prescribing a contour, the content "determines the shape and measure of the container," an approach to drawing from the middle that Delacroix believed he had inherited from the ancients.

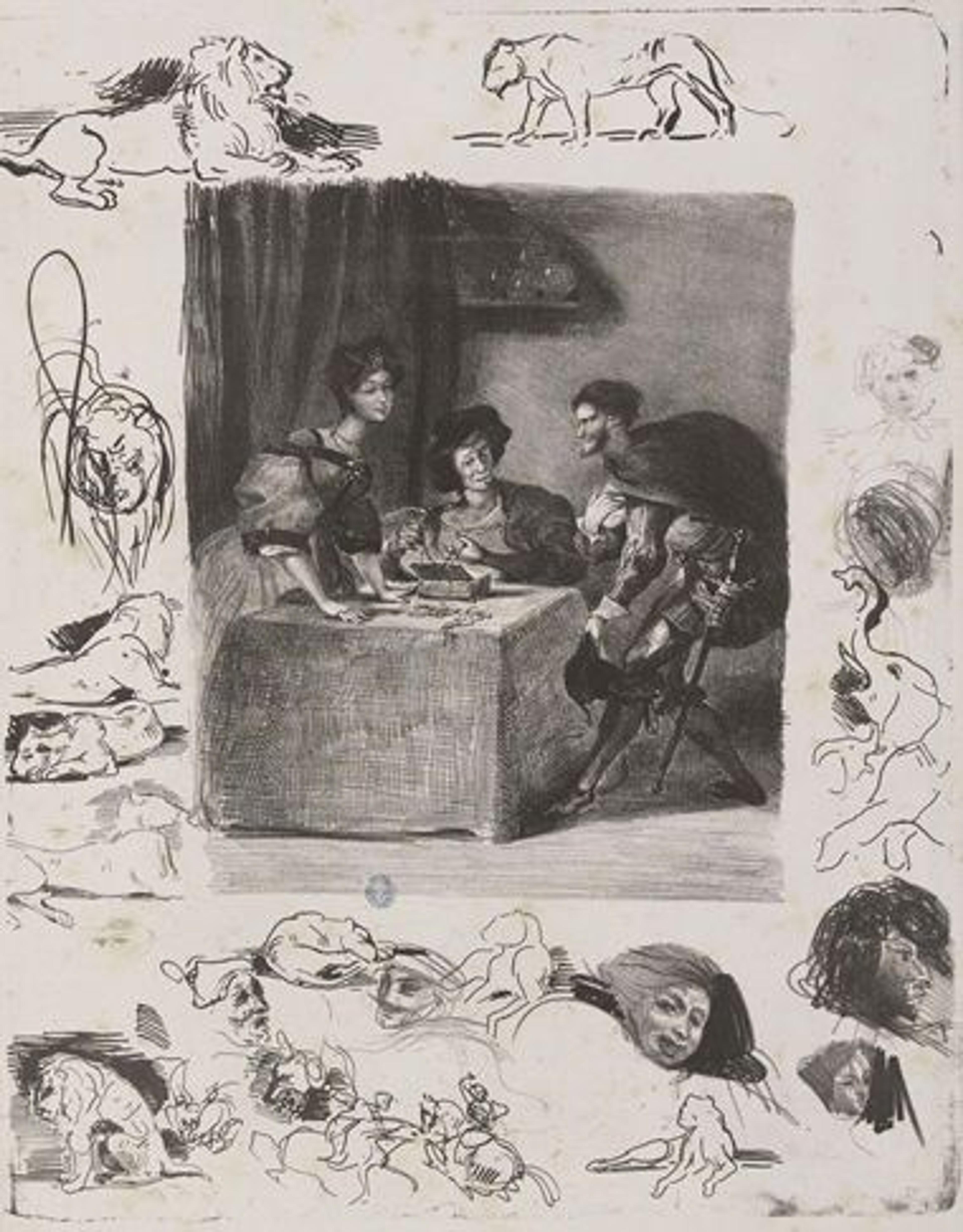

Right: Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863). Faust, plate 9: Mephistopheles Introduces Himself at Martha's House, 1827. Lithograph; first state of seven, with remarques, sheet: 17 x 12 7/8 in. (43.2 x 32.7 cm). Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, Collection Dutuit

The lithographic star of the retrospective is the complete set of first-state proofs of Delacroix's illustrations for Faust, on loan from the Petit Palais. Many of the impressions bear the associative and wandering marginalia, known as remarques, later removed in the published edition. The printer-publisher Charles Motte, who had printed Delacroix's lithographs for Le Miroir in the early 1820s, commissioned Delacroix to illustrate the first French translation of Goethe's celebrated tragedy. (Bound copies of the book are on view in both exhibitions.) Now cited as a landmark of nineteenth-century publishing—as the first significant use of lithography to illustrate contemporary literature—Delacroix's project was a commercial and critical failure at the time. Goethe, at least, appreciated the effort, stating, "M. Delacroix has surpassed the [mental] images that I made for myself from the scenes that I wrote."

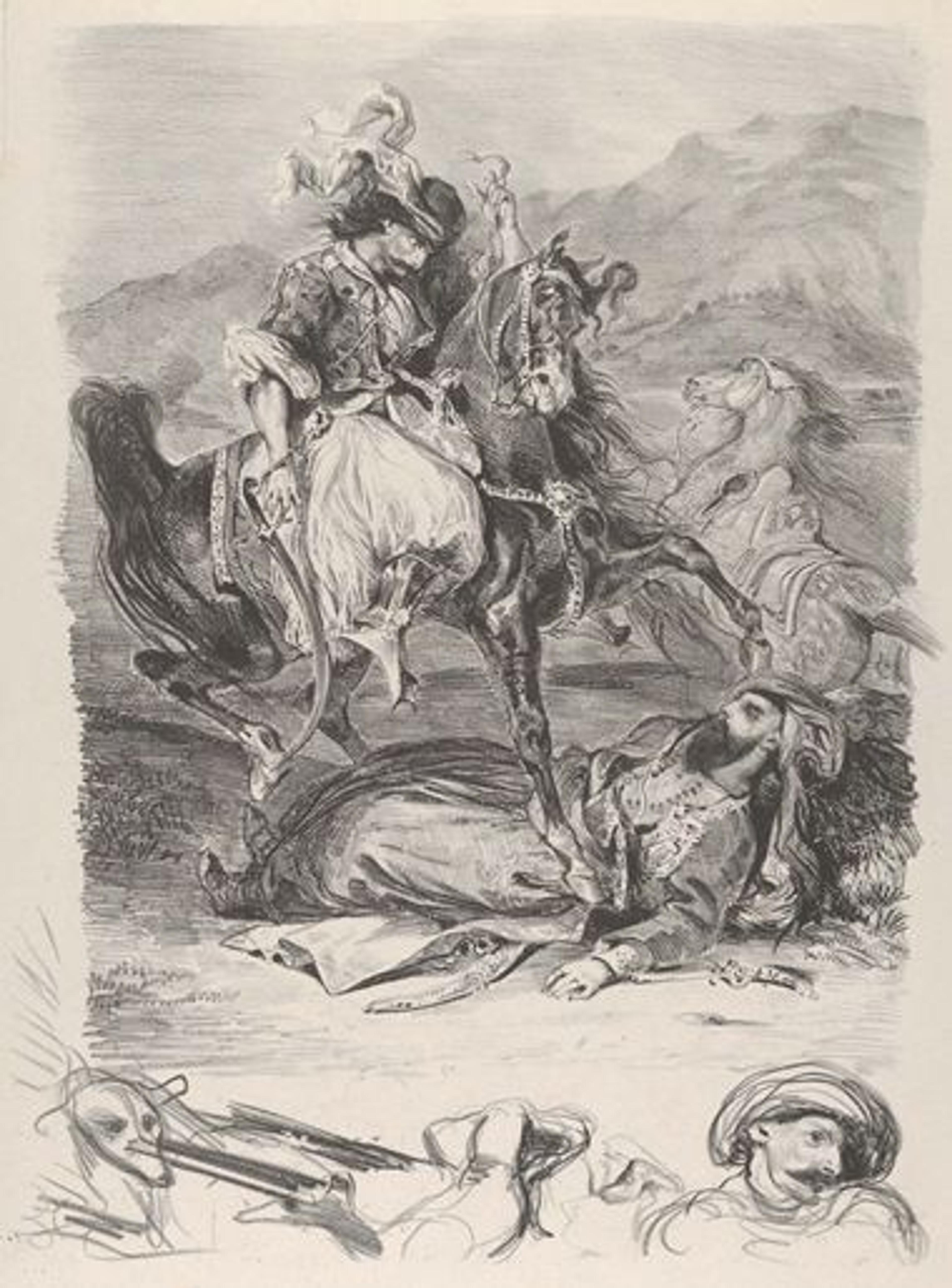

Left: Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863). Combat of the Giaour and the Pasha, 1827. Lithograph; first state of two, sheet: 16 x 11 in. (40.6 x 27.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John J. McKendry Fund, 1996 (1996.424)

The Met has one lithograph featuring remarques in the lower margin executed at around the same time as the Faust series. The subject here is drawn from Byron's poem The Giaour, a Fragment of a Turkish Tale (1813). After reading the French translation, published in 1824, Delacroix noted in his journal the "exchange of two stares, that of the dying man and that of the murderer." The lithograph stages this confrontation between the Venetian giaour (a Turkish term for "infidel") seeking to avenge the death of his lover, and Hassan, who killed her after she fled his harem. The quick and vigorous sketches of the remarques echo the swirling dynamism of the lithograph's composition. It seems Delacroix had planned a suite of illustrations of The Giaour, but undoubtedly due to the poor reception of the Faust series, it remained an isolated artwork in the artist's printmaking oeuvre. He nevertheless continued to explore the theme in his paintings.

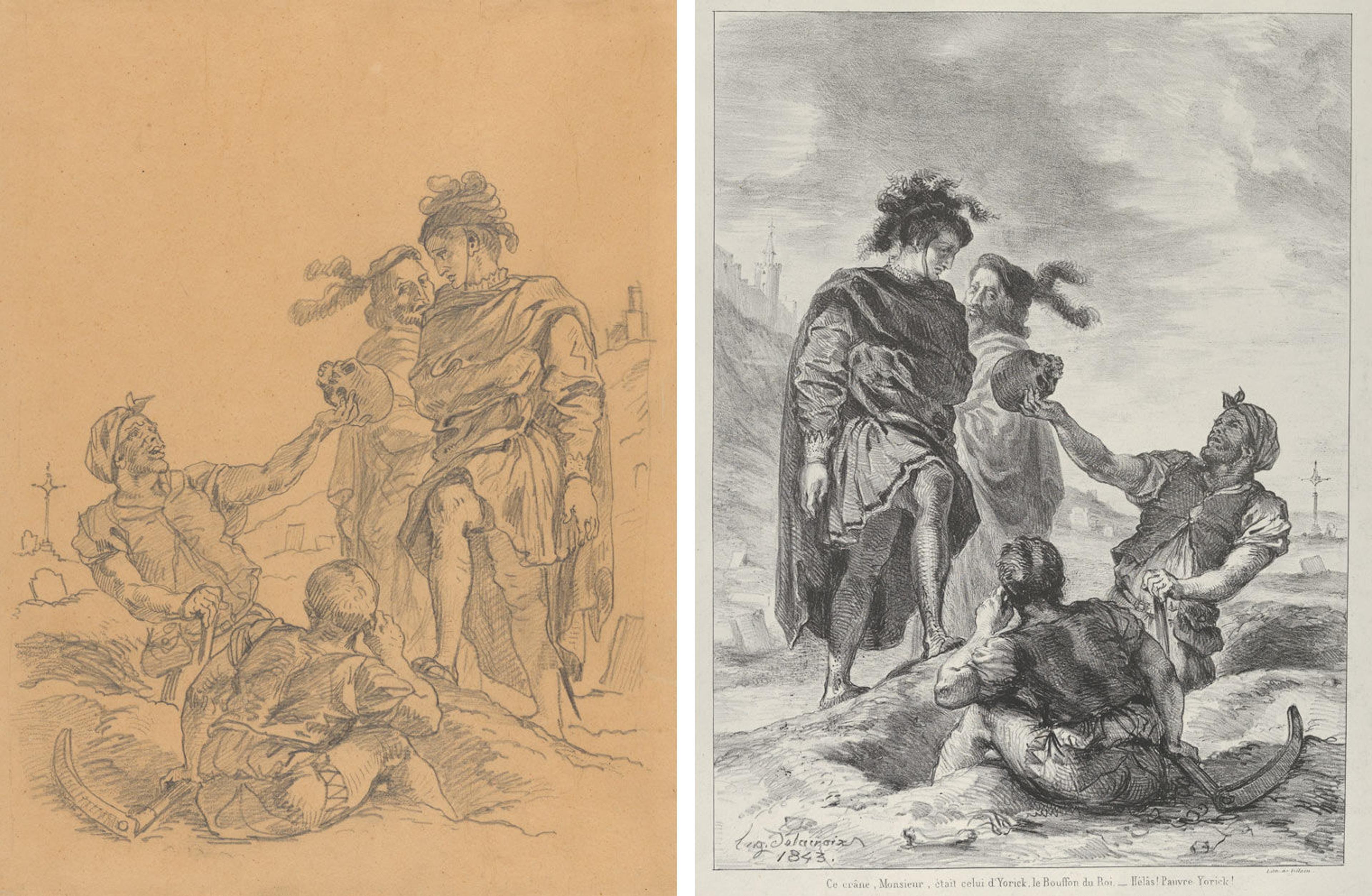

Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863). Left: Alas! Poor Yorick, ca. 1843. Graphite on tracing paper, laid down, 11 1/4 x 8 9/16 in. (28.5 x 21.7 cm). Promised Gift from the Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugène Delacroix, in honor of Debra C. and Jeigh E. Duran. Right: Hamlet and Horatio before the Gravediggers, 1843. Lithograph; second state of four, sheet: 12 1/2 x 9 5/16 in. (31.8 x 23.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1922 (22.56.16)

Delacroix's second major illustration project, his Hamlet suite, features in Devotion to Drawing. Not every plate is on view, but those for which there are related drawings in the Museum's collection are paired together. After completing at least six of the thirteen prints, Delacroix put the project on hold in 1836, likely due to the pressures of state commissions for large-scale public decorations. When he returned to complete it in 1842, his manner of preparing the designs shows the influence of a practice he developed while working on the ceiling for the library of the Palais Bourbon: the use of tracing paper as a means of refining his compositions. The transparent support would also have aided, of course, in the process of reversal required to make the lithographs.

Like Faust, Hamlet was not a commercial success, which may account for why Delacroix made so few prints after 1843. Ultimately only a small circle of insiders collected Delacroix's prints in his lifetime. His printed works were finally discovered and appreciated by a broader public after his estate sale in 1864, much like his drawings.

Note

[1] Segolène Le Men, "Delacroix et l'estampe," in Delacroix, edited by Sébastien Allard and Côme Fabre (Paris: Musée du Louvre and Editions Hazan, 2018), 382.

Devotion to Drawing Related Content

Devotion to Drawing: The Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugène Delacroix is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through November 12, 2018.

View a selection of works presented in the exhibition and take a walkthrough of the galleries.

The exhibition catalogue, by Ashley E. Dunn with contributions by Colta Ives and Marjorie Shelley, is available for purchase at The Met Store.

Delacroix Related Content

Delacroix is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 6, 2019.

View a selection of works presented in the exhibition and take a walkthrough of the galleries.

The exhibition catalogue, by Sébastien Allard and Côme Fabre with contributions by Dominique de Font-Réaulx, Michèle Hannoosh, Mehdi Korchane, and Asher Miller, is available for purchase at The Met Store.