«Tax Day—which falls on April 17 this year—is fast approaching for U.S. residents, who must file paperwork and submit payments to the Internal Revenue Service before this deadline. As another tax season comes to a close, let's take this moment to consider that even those who lived hundreds of years earlier in the ancient Americas paid tributes to governing authorities, much as we pay monetary taxes to our government today. These tributes, however, took many different forms, from iridescent feathers to intricate gold works. The exhibition Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas—on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through May 28—features several works that not only illustrate the various precious materials once collected as tribute, but also shed light on some of the tributary systems of the sixteenth century, including those of the Aztecs and Imperial Spain.»

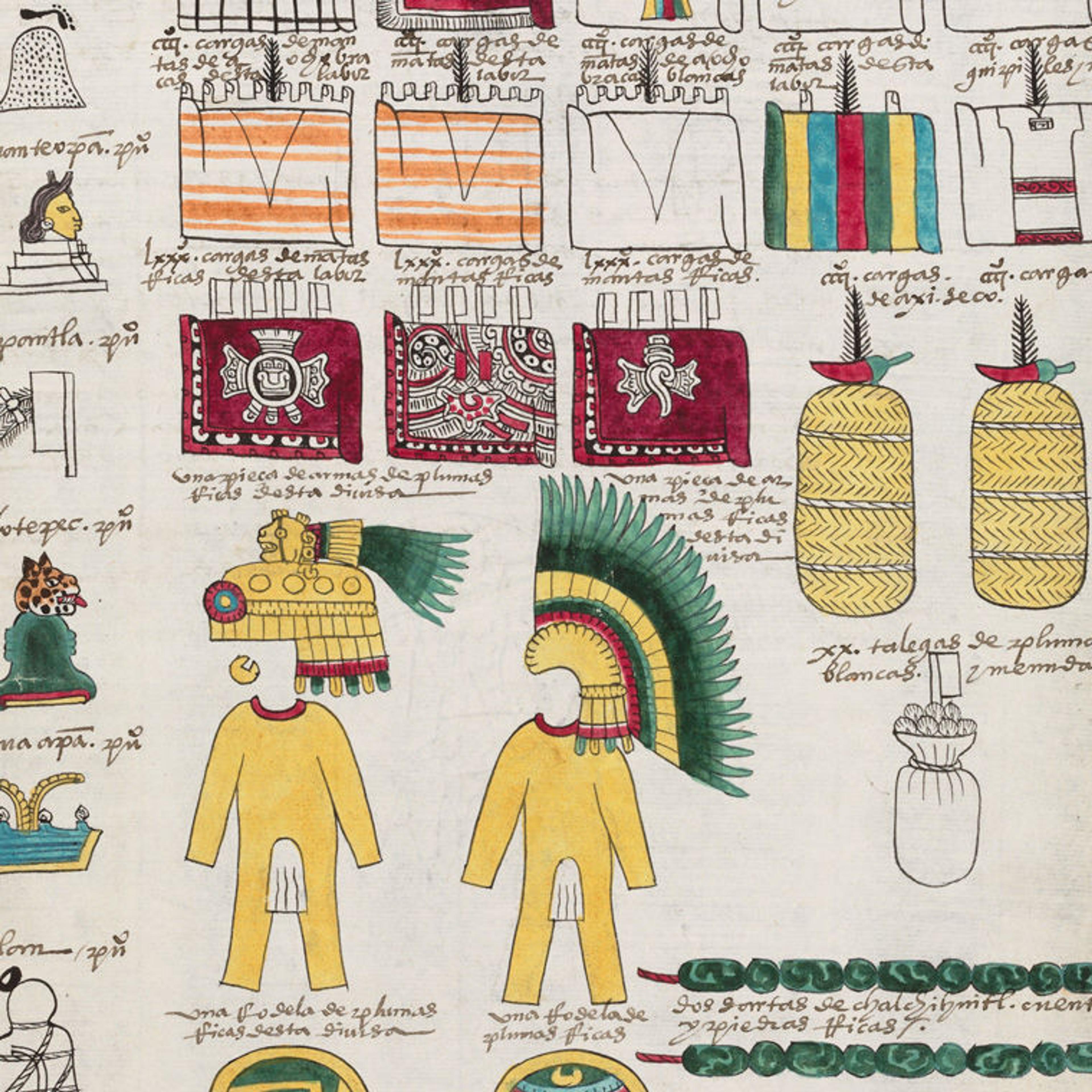

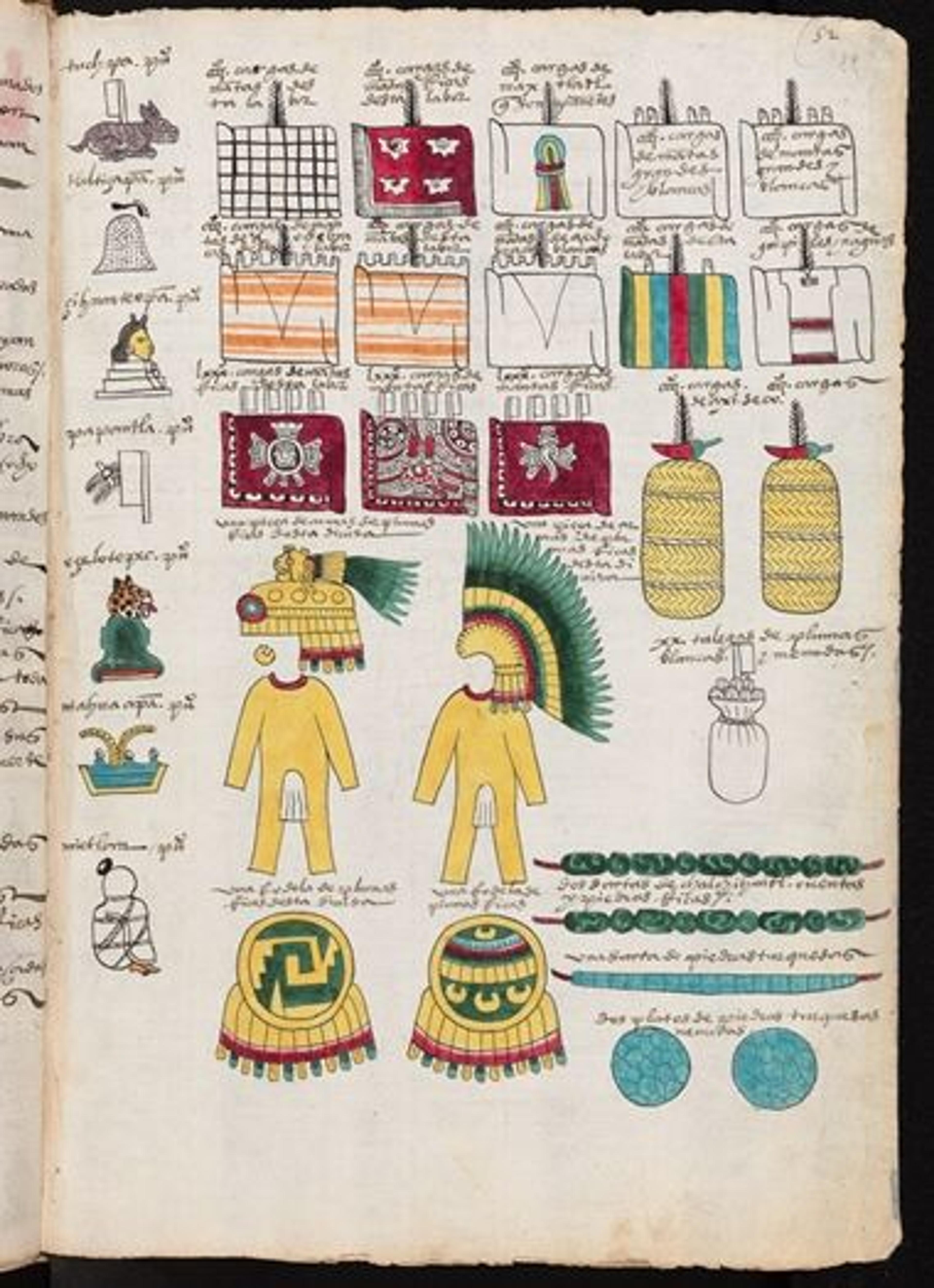

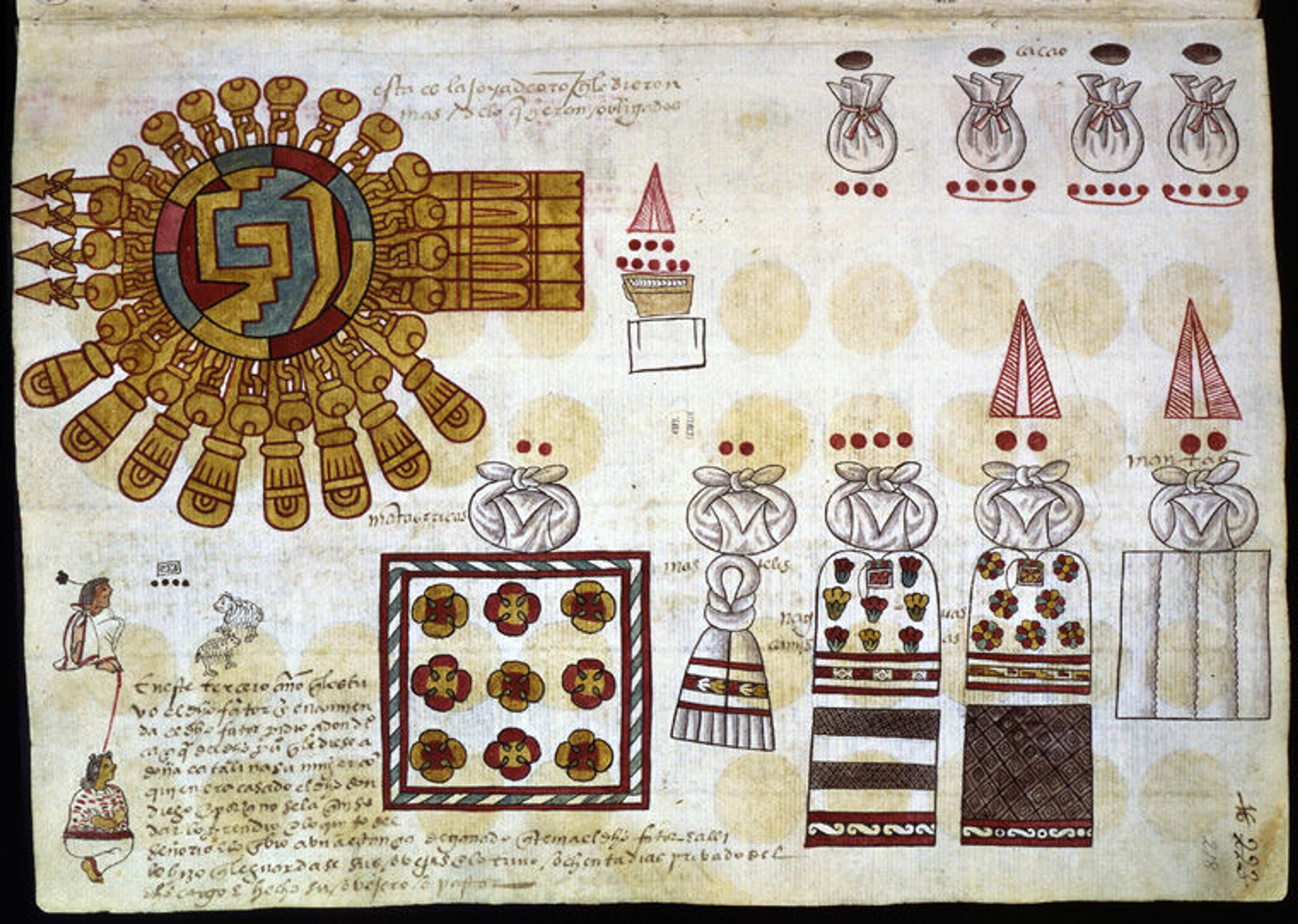

Attributed to Francisco Gualpuyogualcal (Mexican, Nahua, active 16th century) and to Juan González (active 16th century). Codex Mendoza, folio 52 (recto), A.D. 1542. Mexico. Nahua and Spanish. Paper, pigment, closed: H. 12 5/8 in. (32.1 cm). Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford (MS. Arch. Selden A. 1)

Throughout the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, the Aztecs were collecting large quantities of precious materials and luxury items as tribute from thirty-eight provinces spread across present-day Mexico. It was not until 1542, two decades after the Spanish conquered the Aztec Empire in 1521, that tlacuilos (Aztec scribes familiar with the indigenous pictographic system of writing) documented these earlier practices in a manuscript now called the Codex Mendoza. Likely commissioned by Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza for Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor and the King of Spain, this manuscript offers a detailed record of the former Aztec Empire's military conquests, sociocultural traditions, and tribute demands.[1]

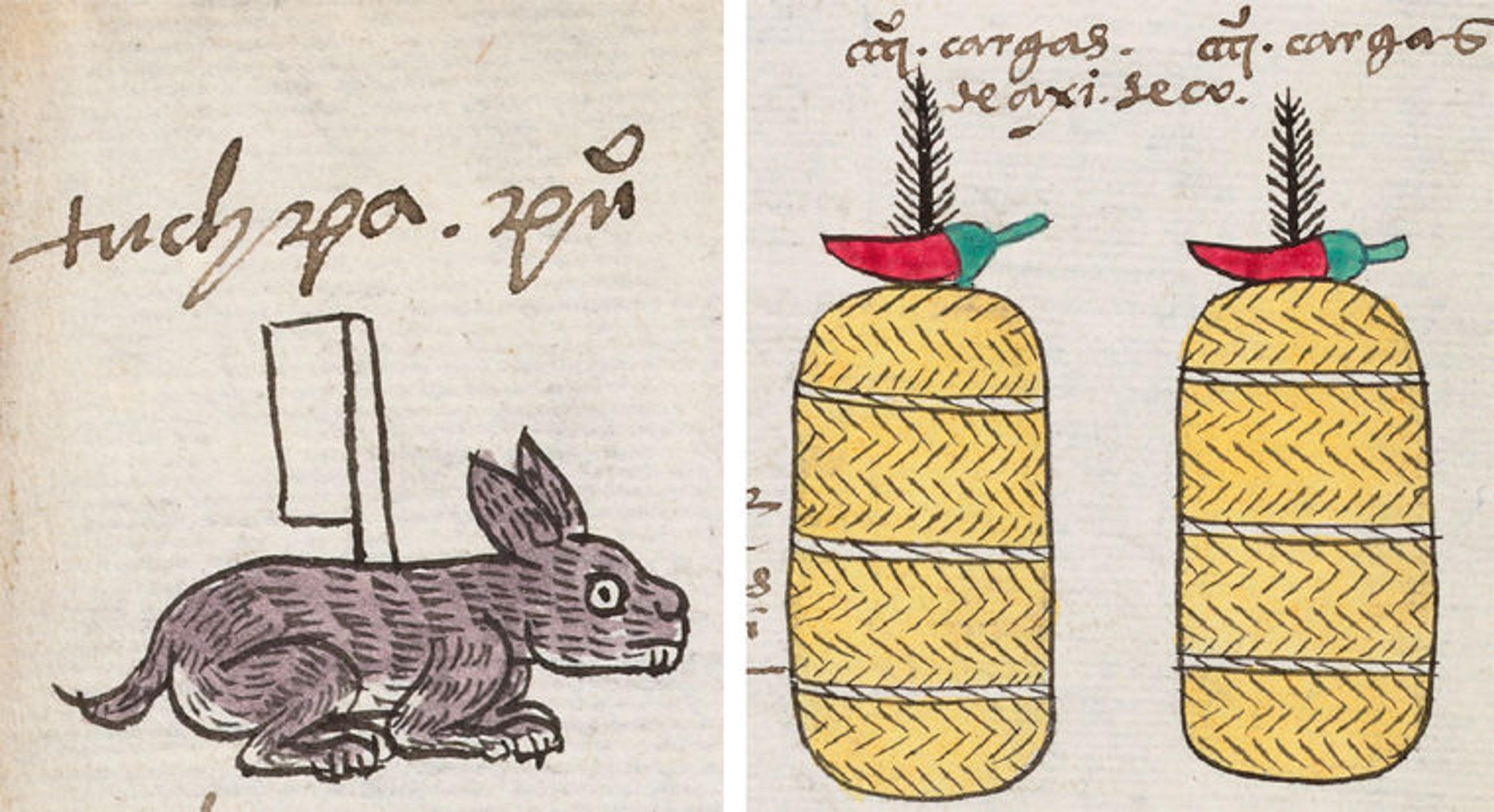

Details from the Codex Mendoza, folio 52 (recto), depicting the glyph for the province of Tochpan, a rabbit with a white banner on its back (left), and pictographic representations of chili peppers collected as tribute (right)

The Codex Mendoza's tribute roll, which lists the goods paid by subject provinces to the Aztec capital, follows a standard format: glyphs naming the tributary towns within each province run down the left-hand margin, while other pictographs identifying materials and items fill the remainder of the page. Folio 52 names seven towns within the province of Tochpan, located near present-day Veracruz on the Gulf Coast of Mexico. As shown in the upper portion of this folio, the bulk of Tochpan's tribute was paid in garments, many with elaborate designs and in brilliant colors. Tochpan also supplied other valuable objects to the empire—including warrior costumes, feather shields, bags of feathers, beads of jadeite and turquoise, and even baskets of dry chili peppers.[2]

Large numbers of textiles, feather works, and precious stones appear throughout the rest of the Codex Mendoza's tribute roll, which suggests that the Aztecs greatly valued these materials. Tributary items were also generally lightweight luxury goods, making them worth transporting across great distances to the Aztec capital.[3] After the Spanish conquest, however, gold quickly usurped other precious materials to become the favored tribute among the conquistadors.

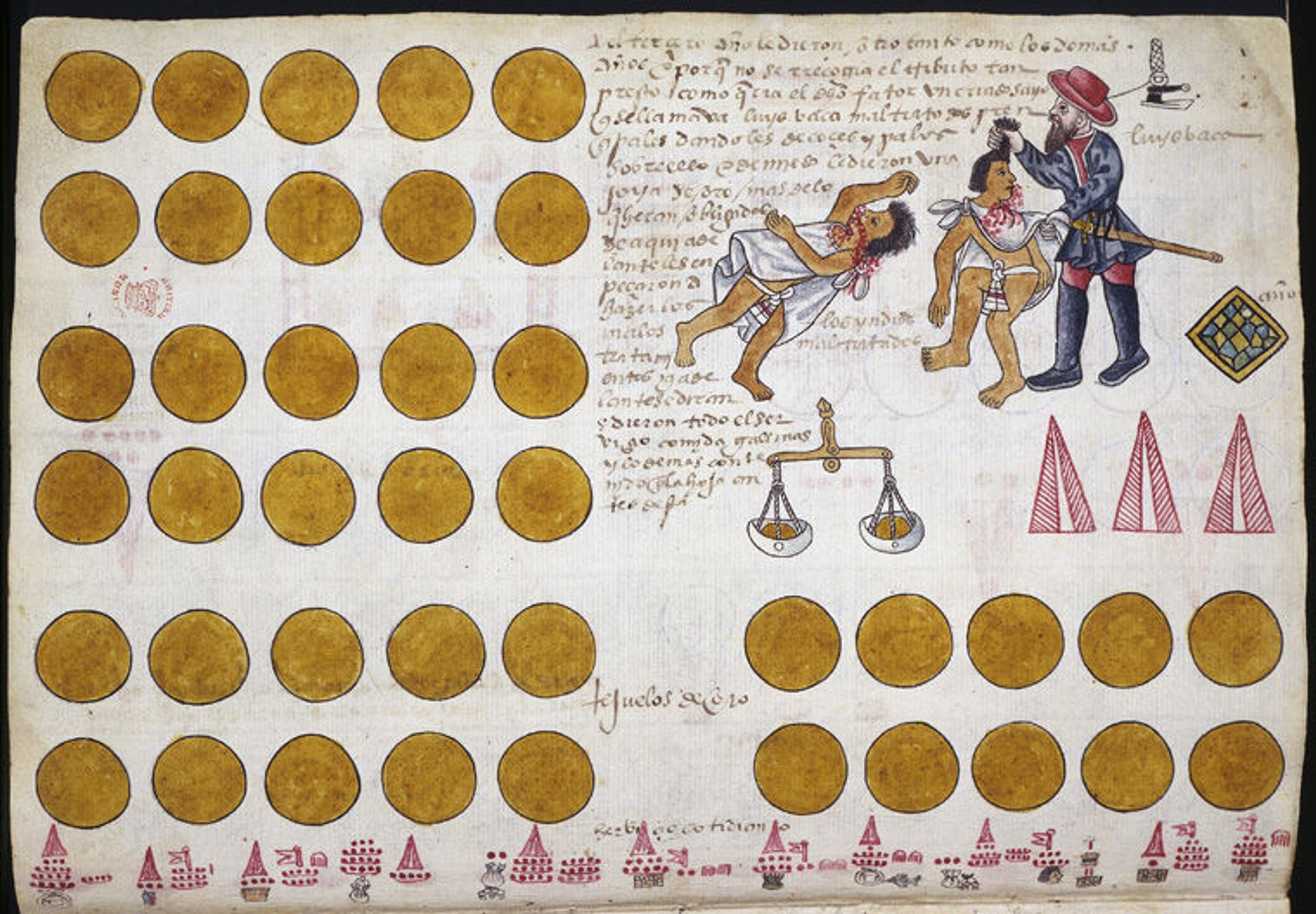

Codex Tepetlaoztoc (Codex Kingsborough), folio 15 (verso), A.D. 1554. Mexico, Tepetlaoztoc. Nahua. Paper, pigment, closed: 11 3/4 x 8 7/16 in. (29.8 x 21.5 cm). British Museum, London (AOA Am 2006 Drg13964). Image © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

Codex Tepetlaoztoc (Codex Kingsborough), folio 16 (verso), A.D. 1554. Mexico, Tepetlaoztoc. Nahua. Paper, pigment, closed: 11 3/4 x 8 7/16 in. (29.8 x 21.5 cm). British Museum, London (AOA Am 2006 Drg13964). Image © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

During the sixteenth century, the Spanish collected vast quantities of gold from newly conquered territories in Mesoamerica. Some of these practices have been chronicled in a manuscript called the Codex Tepetlaoztoc (also known as the Codex Kingsborough). Commissioned in 1554 by the indigenous people of Tepetlaoztoc, once subjects of the Aztec Empire, this manuscript recounts the excessive tribute demands of the encomenderos, conquistadors to whom the Spanish Crown gave control and tribute rights over indigenous communities.[4]

During the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés's three-year reign over Tepetlaoztoc, he required an annual payment of forty pieces of gold, elaborate gold works, numerous textiles, and large quantities of maize. Shortly before control over Tepetlaoztoc passed to another Spaniard, Cortés sent a servant, Luis Vaca, to gather even more items in excess of the normal tribute. Folio 15 from the manuscript depicts a particularly violent episode: on the upper-right corner, Vaca is shown aggressively extracting additional amounts of gold, depicted as disks, from two Tepetlaoztoc noblemen. Folio 16 depicts other valuables Vaca collected, including a gold ornament, cacao, feathers, and textiles.[5]

Right: Depicted here is the Aztec lord Nezahualcoyotl dressed in elaborate feather regalia that likely resembles the precious costumes destroyed by the Spanish conquistadors at Tenochtitlan in 1520. Author: Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl (Nahua-Spanish, ca. 1578–1650). Codex Ixtlilxochitl, folio 106 (recto), A.D. 1582. Mexico, Tetzcoco. Nahua-Spanish. Paper, pigment, closed: H. 12 3/16 x W. 8 1/4 in. (31 x 21 cm). Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France (Ms. Mex. 65-71)

Although the feathers and textiles so valued by the Aztecs remained part of the tribute now paid to the encomenderos, the heavy presence of gold in the Codex Tepetlaoztoc indicates the colonial appetite for precious metals over other materials. Indeed, the Spanish voracity for gold is evidenced even earlier: in 1520, when Spanish conquistadors looted Tenochtitlan—the capital of the Aztec Empire—they seized only the gold and set fire to the rest, destroying greenstone ornaments, feather shields, and finely woven garments that belonged to the Aztec emperor himself.[6]

Through these exploits, the conquistadors amassed great fortunes from expansive regions of the Americas—but even the conquistadors, as powerful as they became, could not escape taxation. Although they were many thousands of miles away from Europe, the Spanish Crown required that conquistadors ship twenty percent of the loot back to Spain as part of the Royal Fifth, an imperial tax levied on all precious materials acquired in the Americas.[7]

Bullion, A.D. 1519–1520. Mexico, Mexico City. Aztec and Spanish. Gold, 9/16 x 10 7/16 x 2 3/16 in. (1.5 x 26.5 x 5.5 cm). Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City, Secretaría de Cultura—INAH (10-220012). Image © Secretaría de Cultura—INAH

Among all of the indigenous objects that were transported to Spain, very few Pre-Columbian gold works were preserved in their original forms. Although some conquistadors acknowledged the craftsmanship of the objects they encountered, gold was indiscriminately melted down into portable bars, such as the roughly cast bullion shown above. Even those gold works that remained unaltered, which were to be sent back as novelties or exotica, were eventually liquidated to finance Spain's military campaigns or to concur with religious ideologies that condemned such non-European objects.[8]

Shield pendant with darts, ca. A.D. 1500. Mexico, Veracruz. Mixtec (Ñudzavui). Gold, H. 4 x W. 3 1/4 x D. 3/8 in. (10.2 x 8.3 x 1 cm). Museo Baluarte de Santiago, Veracruz, Secretaría de Cultura—INAH (10-213084). Image © Secretaría de Cultura—INAH; photo by Michel Zabé / Art Resource, NY

Although exceedingly rare, the works of Pre-Columbian art that survive this colonial period bear testament to the Aztec's mastery in goldworking. The ornament in the shape of a shield pictured above is one such object. Likely looted by Spaniards from a tomb in Oaxaca, Mexico, it features two banners marked with crowned letter C's, which indicate that it was once headed for Spain as part of the Royal Fifth. Fortuitously, the ornament became lost at sea in the sixteenth century when a loaded ship setting sail for Spain sank in the Gulf of Mexico. It was only in the late 1970s that an octopus fisherman discovered dozens of gold objects near present-day Veracruz, including this shield ornament. Had it reached Europe as planned, the ornament would have been melted down like countless other gold works.[9]

Before the Spanish arrived in Mesoamerica, indigenous tributes were composed of shells, greenstone, turquoise, textiles, and feathers, among many other materials. When Spanish conquistadors took control over vast lands in the Americas, extraordinary numbers of luxury items created from these precious materials were destroyed, while unprecedented quantities of gold were extracted from indigenous communities. Although this narrative is most certainly one of drastic change and irrecoverable loss, surviving tributary objects continue to illuminate both the great artistic traditions of the ancient Americas and the fascinating history of tribute systems in the sixteenth century.

Notes

[1] Frances F. Berdan and Patricia Rieff Anawalt, The Codex Mendoza (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1992), 1:xiii.

[2] Ibid., 2:132–33.

[3] Ross Hassig, Trade, Tribute, and Transportation: The Sixteenth-Century Political Economy of the Valley of Mexico (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985), 103–7.

[4] Perla Valle, Códice de Tepetlaoztoc (Códice Kingsborough) Estado de México (Toluca: El Colegio Mexiquense, 1994), 7.

[5] Ibid., 11.

[6] Fray Bernardino de Sahagún (1575–77), Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, trans. and ed. Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble (Santa Fe, NM: The School of American Research and The University of Utah, 1975), 12:48.

[7] Kim M. Richter, "Bright Kingdoms: Trade Networks, Indigenous Aesthetics, and Royal Courts in Postclassic Mesoamerica," in Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas, ed. Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum and The Getty Research Institute, 2017), 108.

[8] Ibid., 108–9.

[9] Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter, eds., Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum and The Getty Research Institute, 2017), 266–67.

Related Content

Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through May 28, 2018

See more digital content related to Golden Kingdoms, including a walkthrough of the recent exhibition in English and in Spanish.

Read more articles in this exhibition's blog series.

Purchase a copy of the exhibition catalogue in The Met Store.