"The Inca . . . acquired innumerable riches of gold and silver and other valuable things, such as precious stones and red shells, which these natives then esteemed more than silver or gold."

—Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa, cosmographer, 1572

Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas explores the development of luxury arts from 1200 B.C. to the beginnings of European colonization in the sixteenth century. Made of precious metals and other substances esteemed for their color and luminescence, these works are distinguished by the value of their materials, their symbolically charged iconography, and their role in expressing social status, political power, and religious beliefs.

In the ancient Americas, metals were employed primarily for ritual objects and regalia, rather than tools, weapons, or currency. These items were considered to be imbued with sacred power by those who created and those who used them. Gold, transformed into objects made for gods and rulers, provides the central narrative and trajectory of the exhibition, from Peru in the south to Mexico in the north. Other materials were often deemed far more valuable, however. Jade, for example, was the most precious substance to the Olmecs and the Maya; and the Incas and their predecessors prized feathers and textiles above all.

These works were often transported across great distances and handed down over generations, making them a primary means for the exchange of ideas across regions and time. Crucial bearers of meaning, luxury arts were especially susceptible to destruction and transformation in the sixteenth century. The works in this exhibition are therefore rare testaments to the brilliance of ancient American artists.

The earliest gold objects in the Americas, found in the Andes, are primarily ornaments that accompanied the burials of powerful rulers. Even in later periods, when knowledge of copper-working enabled the manufacture of tools and weapons, metal objects remained first and foremost expressions of social and political power. Gold was closely associated with the supernatural realm, as were certain shells and stones. Across the ancient Americas the use of such materials--believed to have been emitted, inhabited, or consumed by the gods--linked the wearer to the gods’ powers.

The imagery of these early works speaks to a rich supernatural world of snarling, fantastic beasts and other divine beings. Because luxury arts were relatively lightweight and easily transported, such imagery may have spread quickly across the Andean region, promoting an exchange of ideas.

Kuntur Wasi

Some of the earliest works in gold from the ancient Americas were found high in the Peruvian Andes, most notably at the archaeological site of Kuntur Wasi. Located on a hilltop with commanding views of the surrounding landscape, Kuntur Wasi and its neighbor Pacopampa flourished in the first half of the first millennium B.C., erecting architectural complexes featuring monumental platforms with grand staircases, sunken courts, and carved monuments. Part of a larger religious tradition linked to Chavín de Huántar, an important archaeological site in Peru’s central highlands, Kuntur Wasi also had ties to a coastal culture known as Cupisnique.

Between 1998 and 2003, archaeologists uncovered a series of tombs under a platform at Kuntur Wasi. Some contained gold ornaments made of hammered sheet gold. Ancient Andeans preferred working sheet metal to casting, even for small-scale figures, and treated the material in ways analogous to textiles, perhaps the earliest and most esteemed art form of all.

The hilltop site of Kuntur Wasi in San Pablo, Peru. Photo by Yoshio Onuki

The years between A.D. 200 and 850, once known to scholars as the Mastercraftsman period, witnessed striking developments in ceramic, textile, and, especially, metal arts. Several cultures thrived on Peru's desert coast during this time, including the Nasca to the south and the Moche to the north. The Moche civilization, composed of independent polities that shared a religious and artistic tradition, built monumental structures in rich agricultural valleys and benefitted from the abundant resources of the Pacific Ocean. At times, these separate communities unified; at other times, an intense rivalry existed, fueling an extraordinary florescence in the arts.

Moche artists used gold, silver, and copper to create ritual implements and ornaments. They were particularly inventive in combining metals and forging innovative techniques, including some that were more sophisticated than any known elsewhere in the world at the time. Scientific excavations over the past thirty years have revealed the remarkable achievements of these artists and the role they played in creating an ideology of power through the regalia of the Moche lords.

Sipán

Sipán, in the Lambayeque Valley on Peru's North Coast, is considered to be the richest intact burial site uncovered in the ancient Americas. The objects in the fourteen tombs discovered there manifested intriguing connections with imagery painted on ceramics and yielded important insights into Moche practices and beliefs.

A male between thirty-five and forty-five years old, dubbed the Lord of Sipán, was buried in Tomb 1's elaborate chamber, the most complex found at the site. He was accompanied by two adult males, one adult female, three adolescent females, and one child. The lord's coffin contained extraordinarily fine regalia, including sets of nose ornaments, pectorals, headdresses, rattles, and ear ornaments, similar to those worn by a personage known as a "warrior priest" seen in Moche ceramics.

The partially reconstructed Tomb 1 of the Lord of Sipán. Photo by Sue Cunningham

Dos Cabezas

In the Jequetepeque Valley on Peru's North Coast, excavations at the Moche site of Dos Cabezas have revealed impressive grave goods as well as a wealth of information about Moche burial practices and the culture's broader beliefs.

Tomb 2, one of the richest burials at the site, contained finely modeled ceramics and a funerary bundle with multiple headdresses and nose ornaments, among other objects. Inside the bundle, archaeologists discovered a metal burial mask over the face of an adult male, perhaps eighteen to twenty years old, who was strikingly tall by Moche standards (nearly six feet). A miniature version of the funerary bundle was found in a compartment adjacent to the tomb.

Dos Cabezas, looking south to the Pacific Ocean. The monumental platform was damaged by looters during the colonial period, creating a deep V. Photo by Kenneth Garrett

Huaca Cao Viejo

Located at the edge of the Pacific Ocean, at the mouth of the Chicama River on Peru's North Coast, Huaca Cao Viejo was an important Moche ritual center. Before the late twentieth century, high-status Moche burials were thought to belong to men; however, recent excavations in northern Peru have revealed a number of such tombs built for women. A female ruler now known as the Lady of Cao—named for the site where she reigned, around A.D. 400—was buried with numerous textiles and three double-pronged headdresses made of gilded copper, as well as implements usually associated with men, including twenty-three spear throwers and wooden war clubs covered in gilded copper sheet. Her funerary bundle also included a large number of nose ornaments—forty-four—all of similar size but each with a different design, examples of which are on view here. Two nose ornaments had been intentionally placed in the mouth of the deceased; the rest were found near her head.

View of the tombs of the Lady of Cao and her companions. Photo courtesy of Ira Block/National Geographic Creative

The first Andean empires—states that ruled over extensive and diverse territories—arose in the second half of the first millennium A.D. The Wari Empire, based in Ayacucho, in what is today the central Peruvian highlands, established a trade network that extended some eight hundred miles, south to north, over which llama caravans facilitated the exchange of valued materials such as tropical feathers, marine shells, and camelid wool. On the North Coast, the Lambayeque (also known as Sicán) and later Chimú cultures built upon earlier Moche artistic traditions and expanded production to almost an industrial level.

The Inca civilization, in turn, built on the achievements of these earlier cultures, transforming itself from a small polity with localized influence in the Cusco region into the largest premodern empire in the Southern Hemisphere. With remarkable speed, the Incas conquered much of western South America, some twenty-six hundred miles, from Santiago, the present-day capital of Chile, to what is now the border between Ecuador and Colombia. The Inca state exerted rigid control over its domain, imposing a bold new geometric imperial visual style that it disseminated through ritual and economic practices.

Atahualpa, one of the last Inca emperors, was embroiled in a bitter civil war in the years prior to 1532, fatally weakening the empire at the time Francisco Pizarro and his small band of soldiers from Spain—an even larger and more global empire—arrived in Cajamarca, in present-day Peru.

Chan Chan

At its height, the Chimú Empire (A.D. 1000–1470) had influence over some eight hundred miles of Peru's North Coast, from south of the present-day border with Ecuador to north of Lima. Its capital, Chan Chan, located at the edge of the Pacific Ocean in the Moche Valley. The city center is still dominated by the remains of palaces of the Chimú kings: monumental adobe compounds with massive perimeter walls. The city was famed for its artists, as perhaps a quarter of the population of forty thousand was engaged in craft production. Most artists, if not all, served the king and his court, and the works they created included objects for the ritual gift exchange that lay at the heart of Chimú political economy.

Chan Chan was a rich prize for the Inca Empire when it conquered the North Coast around 1470. The Incas captured the city's gold- and silversmiths and brought them to Cusco, the Inca capital high in the Andes. Chan Chan was heavily looted in the wake of the Spanish Conquest in the sixteenth century, and the palaces were stripped of their contents, including finely wrought vessels in silver and gold, examples of which are on view here.

Chan Chan. Photo © Overflightstock Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

Lands that are now part of Colombia, Panama, and Costa Rica were home to thriving polities that fostered extensive and inventive metalworking traditions. In ancient Colombia and Central America, gold was part of a complex symbolic system associated with divine power. Already considered generative, gold was made more so through its transformation into votive figures or the regalia of political and religious leaders worn in both life and death.

A dynamic trade network existed between these regions and those farther north in Mesoamerica, a cultural area extending from northern Central America to northern Mexico. Ritual axes made of jade—the most esteemed material in Mesoamerica—were traded south to Costa Rica, where artists transformed them into pendants. They would split the axes into halves, fourths, or even sixths, so that their sacred power could be extended.

Malagana

In 1992, an ancient cemetery was discovered below the sugarcane fields of Hacienda Malagana in Colombia's Cauca Valley, leading to the identification of a previously unknown style of metalwork dating to 100 B.C.–A.D. 300. Tombs at the Malagana site held opulent funerary assemblages, including emeralds from the Eastern Cordillera of the Colombian Andes, Spondylus shells from the Pacific Ocean, and extraordinary ornaments made of sheet gold. Although most had been looted prior to scientific excavations, archaeologists were nonetheless able to piece together information about the high-status burials. One tomb was approximately ten feet deep, with a floor laid with slabs of imported white granite. Among other objects, it contained four large gold masks—three over the face of a man, with another at his feet. The masks and probably the unusually large pectorals, some of which are almost twenty inches wide, were made exclusively for burials, while some of the ornaments may have been used during the owner's life.

Sitio Conte

Powerful leaders of the Coclé culture (A.D. 400–1000) were buried in necropolises in the Río Grande valley, near the Gulf of Parita, in Panama. Dozens of rulers, warriors, and attendants were interred with a staggering number of objects, and the bodies were sometimes covered from head to toe with ornaments made from sheet gold, shells, bone, and gemstones. Sitio Conte and nearby El Caño were clearly important burial sites, but no evidence has yet been found to suggest that people lived at these locations.

Excavations at Sitio Conte in the 1930s and 1940s, and more recently at El Caño, have revealed much about Coclé funerary practices and the scale and creativity of the culture's metalworking tradition. Grave 5 at Sitio Conte, one of the largest in the region, contained several interments, including that of an elderly man seated on a wooden stool in a small roofed structure. Among his grave goods were a carved sperm-whale tooth pendant and regalia of sheet gold, such as greaves (shin armor), cuffs, and a helmet. He was accompanied by fourteen attendants, possibly sacrificed in the funerary rite.

El Caño, with the Río Grande Valley in the background. Photo by David Coventry

Mesoamerican rulers valued jade and other greenstones above all other luxury materials. Jade's green color and shiny polish evoked agricultural fertility, particularly young sprouts of maize, the region's staple crop. In the first millennium B.C., the Olmecs buried large quantities of the stone as offerings in the sacred spaces of their monumental centers. Claiming divine status, later Maya kings and queens adorned their bodies with prized materials including jade jewels. Lapidary artists incorporated complex mythological motifs, hieroglyphic scripts, and images of deities into this elite regalia. Because the raw material was difficult to obtain and considered very precious, the Maya reused and recarved objects, including ancient Olmec jades, often passing down valuable and venerated heirlooms over many generations.

The splendor of Maya jade regalia is captured not only by the ornaments but also in their depictions on carved stone monuments, in mural paintings, and in detailed narratives painted on pottery. These images bring the ancient courts to life, providing vivid records of nobles who wore elaborate costumes of jade and other materials such as feather, shell, bone, and textile. Maya rulers received goods as tribute and gave them to their peers as part of diplomatic strategies. Ultimately, the most prized possessions were interred with their owners as funerary offerings.

La Venta

For the Olmecs, jade was important as a ritual material, buried in offerings to gods and ancestors, and, in the form of regalia, an expression of royal status. Olmec rulers likely derived their political power from their control over maize agriculture and expressed this power through the use and display of jade. The Olmecs imported the stone via long-distance trade from the Motagua River valley, in what is today southern Guatemala.

At the ceremonial center of La Venta, near the southern Gulf coast of Mexico, rulers buried massive greenstone offerings including hundreds of serpentine blocks in multiple superimposed layers. Archaeological explorations during the 1940s and 1950s revealed numerous smaller offerings, more than three thousand sculptures and body adornments in various types of greenstone. Some such works were also found in tombs and may have belonged to Mesoamerica's earliest rulers. Bordered on the north by a row of three colossal stone heads and on the south by a monumental pyramid platform, the ceremonial center created a prescribed space for elite rituals.

La Venta, with the pyramid platform in the background and replicas of monumental sculptures. Photo by Rebecca B. González Lauck

Palenque

The rulers of Palenque, a Maya site nestled in the misty hills of Chiapas, cultivated generations of innovative architects, engineers, artists, and scribes. Recent archaeological work and epigraphic decipherments have opened a window into the lives of Palenque's kings and queens.

K'inich Janaab Pakal I, the greatest ruler of Palenque, took the throne in A.D. 615, at age twelve. He subsequently renovated the royal palace, which features arched rooms with wider and airier interiors than those found in any other Maya city, as well as a rare multistory tower. His descendants buried him in the Temple of the Inscriptions and covered his body in imported imperial jade: a beaded collar, bracelets, and a mosaic mask. His wife, the queen Lady Tz'akbu Ajaw (called the Red Queen by archaeologists), was buried in the adjacent funerary temple, with a malachite mask.

K'inich Ahkal Mo' Naab III, who took power in A.D. 721, commissioned extensive programs of relief sculptures and other works, including the platform panels of Temples XIX and XXI. Through these sculptures, one of the last rulers of the Palenque channeled the power of the founding deities and his illustrious ancestors.

Palenque, with the palace at left and the Temple of the Inscriptions and Temple XIII at right. Photo by Danny Lehman/Corbis/VCG

Chichén Itzá, on Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula, was a large Maya urban and ritual center that drew pilgrims from across Mesoamerica and Central America. The groundwater there had eroded the limestone bedrock, creating a cenote—a large sinkhole filled with water—that became the focus of devotional practices for many centuries. In Maya cosmology, cenotes were vital portals between the earthly realm and the watery underworld, and they were often depicted as the gaping, bony jaws of a great centipede. Over centuries, visitors made offerings at the site.

In the twentieth century, dredging and archaeological projects at the Sacred Cenote recovered human remains and hundreds of objects, ranging from simple wood figures to royal regalia. These offerings, made by the local Maya and by artists from more distant regions, include a striking number of objects from remote lands: gold bells and figurines from Panama and Costa Rica, as well as jade ornaments from Maya kingdoms deep in the tropical forests, such as Piedras Negras (Guatemala) and Palenque (Chiapas, Mexico). Many of the works had been intentionally broken, crumpled, or burned as part of their ritual sacrifice.

The Sacred Cenote at Chichén Itzá. Photo by Kim N. Richter

After the decline of the Classic period civilizations in the ninth century A.D., new Postclassic kingdoms and city-states emerged, some of which rivaled the splendor of earlier times. Long-distance trade routes opened up regions that had been less accessible, expanding access to exotic goods, and precious materials and luxury works circulated as gifts and tribute via elite exchange networks. The influx of new types of raw materials, such as turquoise from what is now the southwestern United States, as well as specialized technical knowledge, such as new metalworking techniques from South and Central America, spurred artistic innovation throughout the centuries that followed.

During the fourteenth century, the Mexicas, an ethnic group from the north, migrated to central Mexico and established themselves on an island in Lake Texcoco. From humble origins, they quickly rose to power through military acumen and strategic marriages. Based in Tenochtitlan (now buried under Mexico City), the Mexicas formed a political alliance with two neighboring cities, and together established the Aztec Empire (also known as the Triple Alliance) that controlled large parts of Mesoamerica. The empire came to an abrupt end with the arrival of the Spaniards, who conquered Tenochtitlan in 1521.

Monte Albán

The Mixtecs (or Ñudzavui, meaning "people of the rain place"), who flourished in southwestern Mexico during the Late Postclassic period (A.D. 1200–1521), produced exceptional, innovative artworks in various media, notably screenfold manuscripts (or codices) painted in vibrant colors on animal hide, delicate mosaics that combine turquoise with other precious stones and shells, and distinctively wrought gold adornments. They adapted and perfected metallurgical practices introduced from Central and South America, such as lost-wax casting and the false-filigree technique.

Monte Albán, perched upon an artificially leveled mountaintop, strategically overlooks the three central valleys of Oaxaca. A Mixtec tomb excavated at the site in 1932 revealed a rich funerary offering, including 121 works made of gold, 24 pieces of silver, and 2 gold-and-silver works, alongside objects made of other rare, valued materials. These offerings highlight a shift in artistic practice and an increasing preference for gold as the preeminent luxury material.

The Zapotecs (or Bènizàa, meaning "people of the clouds") originally created the tomb during the Classic period (A.D. 200–900), and it was later occupied in the Postclassic period by the Mixtecs, who revered the ancient site

Monte Albán. Photo by Ovidiu Hrubaru/Alamy Stock Photo

The Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan

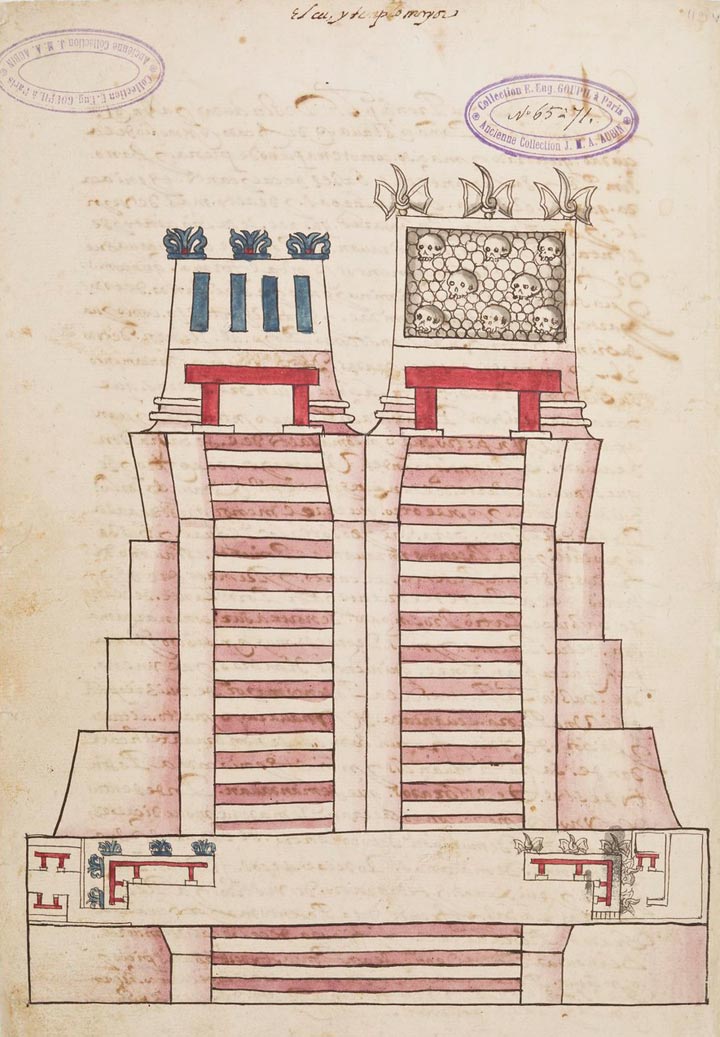

Between A.D. 1428 and 1521, the vast Aztec Empire dominated large parts of Mexico and was ruled by an alliance of three city-states: Tenochtitlan, Tetzcoco, and Tlacopan. The Templo Mayor (Great Temple) was the urban and religious center of Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Mexica people. Its double-pyramid platform topped by twin temples was built in successive stages, each new phase replicating and covering the former. The Templo Mayor's southern half was dedicated to Huitzilopochtli, the Mexica patron god associated with war and the sun, while the northern half was devoted to Tlaloc, the rain god with ancient Mesoamerican origins.

Razed and eventually buried following the Spanish Conquest, the temple was rediscovered in 1978 next to Mexico City's main square. Excavations have uncovered many offerings deposited during ritual ceremonies. As Tenochtitlan rose from a tribute-paying city to the imperial capital, offerings at the Templo Mayor reflect increasing access to foreign materials such as jade, turquoise, and mother-of-pearl, symbolizing Mexica domination over its own far-flung, tribute-paying provinces.

Left: Double pyramid platform with twin temples at Tetzcoco, thought to closely resemble the Templo Mayor. Codex Ixtlilxochitl, Folio 112. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms. Mex. 65-71

During the sixteenth century, the Spanish Conquest brought destruction to the indigenous cultures of the Americas. Local rulers were assassinated, temples were razed, and native populations were devastated by diseases introduced by Europeans. Once Spanish rule was established, the wealth of the Aztec and Inca Empires and a multitude of other kingdoms was appropriated and diverted to Europe, particularly to Spain. Christian clerics soon arrived in the Americas, with the fervent mission to spread God's word and extinguish pagan religions.

Indigenous peoples, especially in Mexico, were perplexed by the Spanish obsession with gold, as they considered jade, turquoise, shells, feathers, and textiles to be far more valuable. In contrast, the Spaniards happily traded green glass beads for gold objects, which they melted down for easy storage and shipment. Despite this cultural rupture, indigenous artists adapted to the new colonial context and continued to practice traditional arts. This melding of customs and beliefs was especially evident in missionary schools, where native artists created Christian images and artworks in media such as feather mosaic. The Americas quickly became the center of a global mercantile crossroads, in which exotic goods and artistic knowledge from Europe and Asia circulated and blended with ancient indigenous traditions.

Banner image: Pendant (detail), 1 B.C.–A.D. 700. Tolima, Colombia. Gold, 12 5/8 x 6 3/8 in. (32 x 16.2 cm). Museo de Oro, Banco de la República, Bogotá (O06061). Blog series image: Nose ornament, A.D. 525–550. Peru. Moche. Gold, H. 1 15/16 in. (5 cm). Museo de Sitio de Chan Chan, Huanchaco, Peru. Ministerio de Cultura del Perú