«Michelangelo's love for aristocratic young men, his poetry, and his gift drawings are among the many topics explored in the exhibition Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through February 12, 2018. As discussed in the catalogue by the exhibition's curator, Carmen C. Bambach, the artist's homosexuality was an open secret among his contemporaries and integral to understanding much of his artistic production, despite frequent efforts to ignore or censor the topic beginning soon after the artist's death in 1564.»

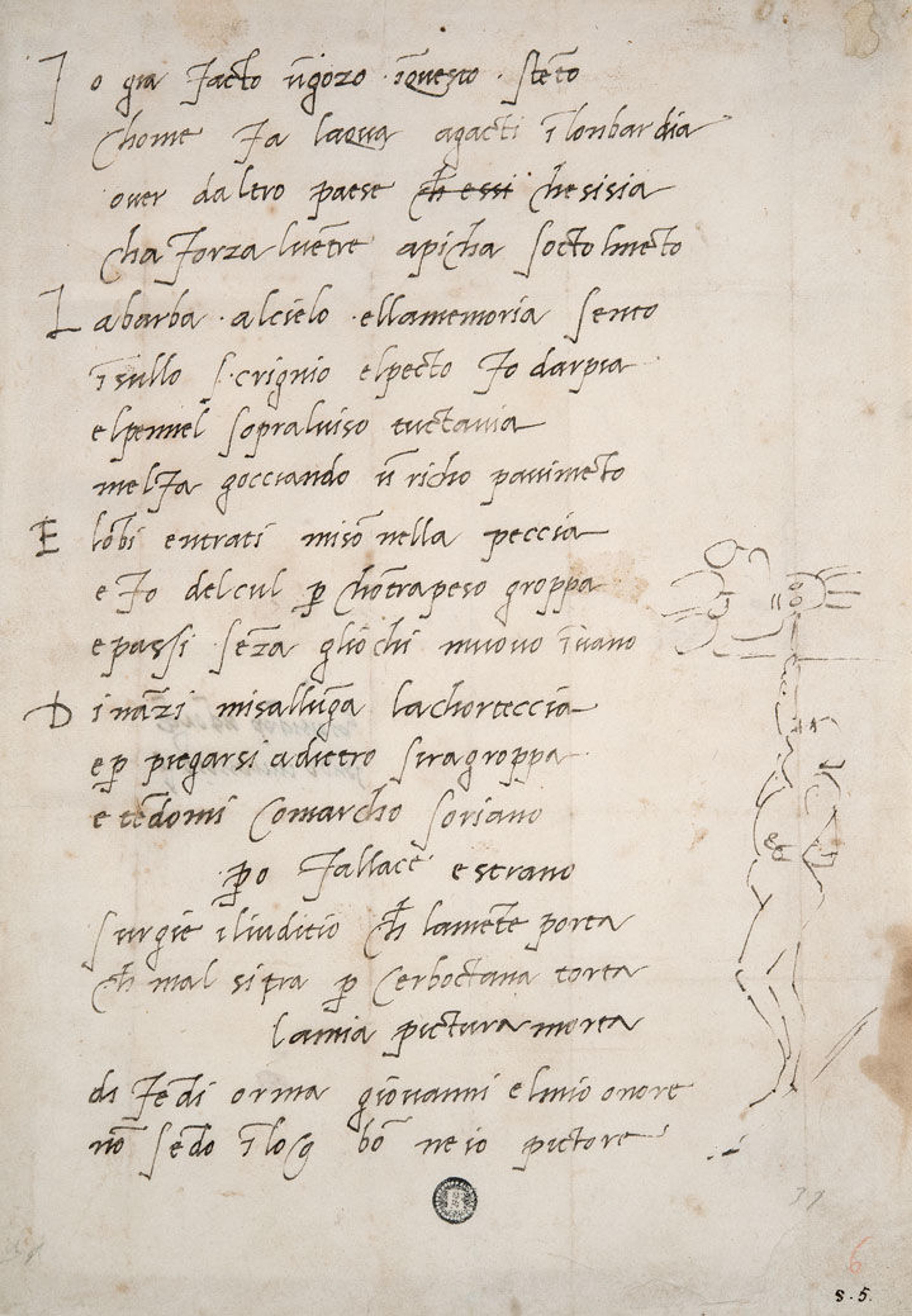

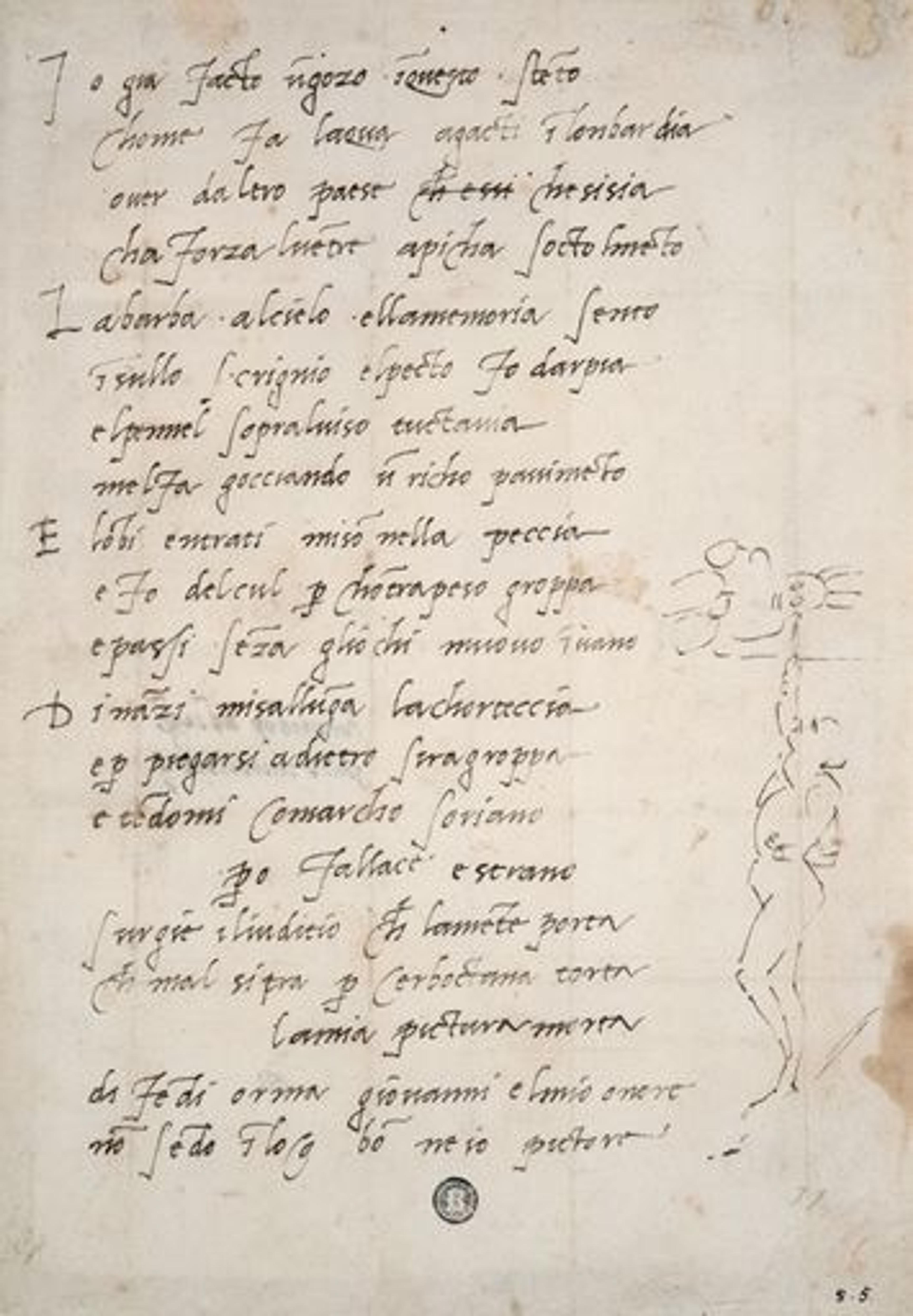

Left: Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475–1564). Sonnet "To Giovanni da Pistoia" and Caricature on His Painting of the Sistine Ceiling. Pen and brown ink, sheet: 11 1/8 x 7 7/8 in. (28.3 x 20 cm). Casa Buonarroti, Florence Archivio Buonarroti (XIII, fol. 111)

On the occasion of the exhibition, I interviewed James M. Saslow, emeritus professor of art history, theater, and Renaissance studies at Queens College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (as well as my former graduate advisor). A pioneer in the study of homosexuality and the visual arts during the Italian Renaissance, Saslow began his work on Michelangelo with his first book, Ganymede in the Renaissance: Homosexuality in Art and Society (1986), which led to his second, The Poetry of Michelangelo: An Annotated Translation (1991), the authoritative English translation of the artist's poetry.

Ahead of the Sunday at The Met program on January 7, which will feature Professor Saslow as one of the speakers, we discussed topics explored in the exhibition—including Michelangelo's decades-long practice as a poet, his relationships with Tommaso de' Cavalieri and Vittoria Colonna, the meaning of his gift drawings, and the study of Michelangelo's homoeroticism throughout the centuries since his death.

Jeffrey Fraiman: Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer includes 133 works on paper by Michelangelo, including quick sketches, figure drawings after the model, cartoons, finished demonstration drawings, gift drawings, as well as poems and letters, both in draft and finished form. How should a visitor consider his writings and drawings together?

James Saslow: Drawings are an index of the creative process, a thought committed to paper. We love looking inside the minds of creative people because presumably there is more going on in there emotionally and aesthetically than in the average person. One of the many fascinating parts of this exhibition and its catalogue is getting inside Michelangelo's mind.

Poetry is very much the same. A poem can explicitly state a feeling in a way visual arts cannot, and therefore poems are even more of a mirror into the mind than a drawing or painting. That's the old classical line: paintings are mute poetry. Michelangelo's interested in both drawing and writing, text and image, much more than any other artist in his time, and more than any artist until William Blake. This has something to do with an intense need to express himself and get his ideas and feelings on paper and out into the world. He's the most personal of artists. He says in several poems that when you make a work of art, you put yourself into it. It becomes you.

Jeffrey Fraiman: Michelangelo wrote hundreds of poems over many decades. How did he view his own writing?

James Saslow: He was ambivalent about it. On one hand he took it seriously, and it was an outlet for important ideas that were too complex to put into an artwork. On the other hand he said, "Writing is not my profession" (non è mia arte). Often when Michelangelo sent a poem to somebody, he accompanied it with a letter that made fun of it. He's aware that he's not a genius poet. But it matters to him much more than other artists. I think it's because poetry can express ideas more overtly than visual art.

Jeffrey Fraiman: The exhibition celebrates Michelangelo as Il Divino, the divine one. At a certain point, drawings by his hand were seen as divine, sacred objects, akin to relics. How was his poetry received?

James Saslow: There was an expectation around this time—if an artist was going to claim the status of a liberal artist, rather than a mere craftsman—that you had to show ability to think abstractly. Writing is how you do that. So a lot of artists wrote, whether it was poetry or prose or art theory, to show that they had intellectual as well as manual skill. Many other artists at the time wrote poetry, but most did it casually. Michelangelo wrote regularly until a few years before his death.

Michelangelo did receive serious praise for the poetry late in life from Benedetto Varchi during a prestigious public lecture in 1547. Michelangelo was thrilled, of course. However, I don't think he was ever treated as a literary lion in the modern sense.

Left: Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475–1564). Studies for Night in the New Sacristy of San Lorenzo and Other Anatomical Motifs. Grayish black chalk, 11 x 13 1/2 in. (28 x 34.3 cm). Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, Florence, (18719 F). Right: Detail of Michelangelo's Night sculpture in the Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici in the New Sacristy, Church of San Lorenzo, Florence. Public-domain image

Jeffrey Fraiman: The exhibition contains several of Michelangelo's studies for his allegorical marble figures for the tombs of the Medici in the New Sacristy, which seem to confirm the idea many visitors have that Michelangelo used male models for his female figures. A study from the Uffizi, for example, shows that the model had male genitalia, while the finished marble sculpture of Night is female.

James Saslow: You have to be careful not to make too much of the fact that he always used male models. Most people did at the time, since there were limitations on the availability of female models. If you disrobed in front of man who wasn't your husband, you were no better than a prostitute. So it was common in workshops to simply use other boys and men in the workshop as models.

That said, Michelangelo went further than anyone in imbuing his female characters with a male physique and facial features, because to him, ideal beauty is male. That was the official art theory of the time, going back to the Bible and Aristotle, the belief that men are better than women, and that female bodies are some imperfect version of the male. There is a whole cultural heritage of patriarchal values there that is not unique to him. But he's also fascinated by gender ambiguity because he's experiencing it in his love for men and for Vittoria.

Jeffrey Fraiman: Michelangelo met Tommaso de' Cavalieri, of an ancient Roman noble family, in 1532. Tommaso was around 39 years younger than Michelangelo, who developed intense, passionate feelings for the youth that he expressed in letters, poems, and gift drawings. The nature of their relationship is discussed in some depth in the catalogue. Questions about the relationship between Tommaso and Michelangelo are some of the most frequently asked by visitors to the exhibition.

James Saslow: Clearly Michelangelo felt a sexual attraction. Whether the two of them actually ever consummated that desire, nobody knows, and that was very unlikely, because Tommaso was an aristocrat, and Michelangelo of a much lower status. But it's immaterial whether they ever actually kissed, let alone anything further. In modern understanding, homosexuality is a psychological attraction, and you can feel the attraction whether you satisfy it or not.

The exhibition provides a case study for the emergence of homoerotic self-expression in modern times. Michelangelo's poetry and drawings for Tommaso are the first example we have in high art of one man declaring his passion for another in such a confessional manner. A few other poets wrote some homoerotic verse before Michelangelo—like Poliziano, who was his teacher—but with Michelangelo it's the first time you have a significant body of work meant to express passionate feelings between men. We get to know both parties, and how it played out in real time.

Giorgio Giulio Clovio (Julije Klović) (Croatian, 1498–1578), after a lost drawing by Michelangelo. Rape of Ganymede. Black chalk, 7 5/8 x 10 7/8 in. (19.5 x 27.5 cm). The Royal Collection / HM Queen Elizabeth II (RCIN 913036)

Jeffrey Fraiman: Michelangelo's Rape of Ganymede was one of his most famous drawings for Tommaso, which survives only through copies, probably as a result of censorship, as Carmen Bambach proposes. It is best recorded in the famous copy by Giorgio Giulio Clovio. In the myth, the shepherd boy is kidnapped by Jupiter in the guise of an eagle to serve as cup-bearer to the gods. What can the choice of that theme tell us about the relationship between Michelangelo and Tommaso?

James Saslow: The Ganymede is about the rapturous feeling that comes when you are embraced by someone, and Michelangelo is imagining himself to be Ganymede wrapped in the embrace of the eagle and swept up to heaven. We have the same ambiguity in English, in the expression "carried away," which refers to either being literally physically dragged somewhere or being emotionally overwhelmed. In the drawing Michelangelo is clearly confessing that, "When I am with you, I am carried away by this rapturous admiration or desire."

It's definite that the gift drawings were known to other people and were much admired. In a revealing episode, Cardinal Ippolito de' Medici came to visit and asked to borrow the drawings so he could have them copied, and Tommaso tried to prevent that, but failed. He wrote to Michelangelo, "I did my best to save the Ganymede," which suggests that of all the drawings, they're aware that the Ganymede most expresses sensitive or scandalous relations between them.

Jeffrey Fraiman: Michelangelo was devoutly religious, more and more so as he got older. How do we reconcile the two sides of him, his intense spirituality and his love for these young men?

James Saslow: Michelangelo had two passions: one was men, and the other was God. He was an intensely religious person and that became more prominent in his later life. He lived through a period of religious reform and knew a lot of church reformers in this era of a return to piety and orthodoxy. The problem was that he felt these officially taboo desires for various men; Tommaso de' Cavalieri was the most important, but there were several others we know by name, like Febo di Poggio, who also received a poem addressed to him.

Michelangelo was always torn between the desire for passionate union with another human being, preferably male, and the belief that such desire could lead to sin. He wrestled with that in the poems for Tommaso. Later in life, he came to the conclusion in the last poems that nothing mattered except attaining the love of God, so he renounced any intimate human relationship.

Jeffrey Fraiman: How was Michelangelo's friendship with Tommaso viewed by others, whether Tommaso himself or Michelangelo's contemporaries?

James Saslow: I think Tommaso de' Cavalieri was flattered, but he was also somewhat alarmed, because there were rumors circulating that their relationship was not entirely proper. Pietro Aretino's letter to Michelangelo alludes to general gossip, and says, "You should give me the drawings I'm asking for, because that would help get rid of the rumors that only certain 'Gerardos' and 'Tommasos' can get drawings from you." He was basically saying, "Everybody knows you're giving drawings to these young men, and that sounds suspect." Michelangelo and Tommaso were both nervous about people talking; the artist said in one poem to Tommaso, "Don't listen to the evil, cruel, and stupid rabble who impute things to me that they do themselves."

As far as we know, Tommaso was not homoerotically inclined, so he probably was a little dismayed by this. Things probably cooled down after the initial intensity when they first met, but there remained meaningful sympathies between the two, and they stayed close for the rest of Michelangelo's life. Tommaso was at his deathbed, and was charged with finishing Michelangelo's architectural plans on the Capitoline Hill, so clearly he was a trusted, lifelong friend.

Jeffrey Fraiman: In the exhibition, soon after the gift drawings for Tommaso, viewers see Michelangelo's later devotional drawings, including a section devoted to his friendship with the marchesa Vittoria Colonna (1490–1547). How does Michelangelo's relationship with Vittoria compare to his relationship with Tommaso, and how does his poetry change?

James Saslow: He met Vittoria Colonna not long after Tommaso, probably when the most intense phase of his relationship with Tommaso was receding. Vittoria was writing religious verse, and it's another case of him recognizing a kindred spirit. In this case it's about religion primarily, although Vittoria is also aware of the arts and was a bit of a connoisseur. He sends her poems and drawings as well, like the Pietà featured in the exhibition from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

Right: Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475–1564). Pietà for Vittoria Colonna. Black chalk on paper, 11 3/8 x 7 7/16 in. (28.9 x 18.9 cm). Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (1.2.0.16)

He was very smitten by her. I don't think it was a passionate lust, because he didn't meet her until he was 60 and she was a homely widow, rather devout and austere. I am sure she never encouraged any romantic connection.

Michelangelo wrote poetry to her that reverts to the traditional, accepted Petrarchan mode for a man addressing his adored woman. What's unconventional is that he treats her more like a man than a woman. He refers to her as "a man within a woman" (un uomo in una donna), and uses metaphors to describe her that assign Vittoria the traditionally masculine, active role in their relationship and cast him in the passive, feminine role.

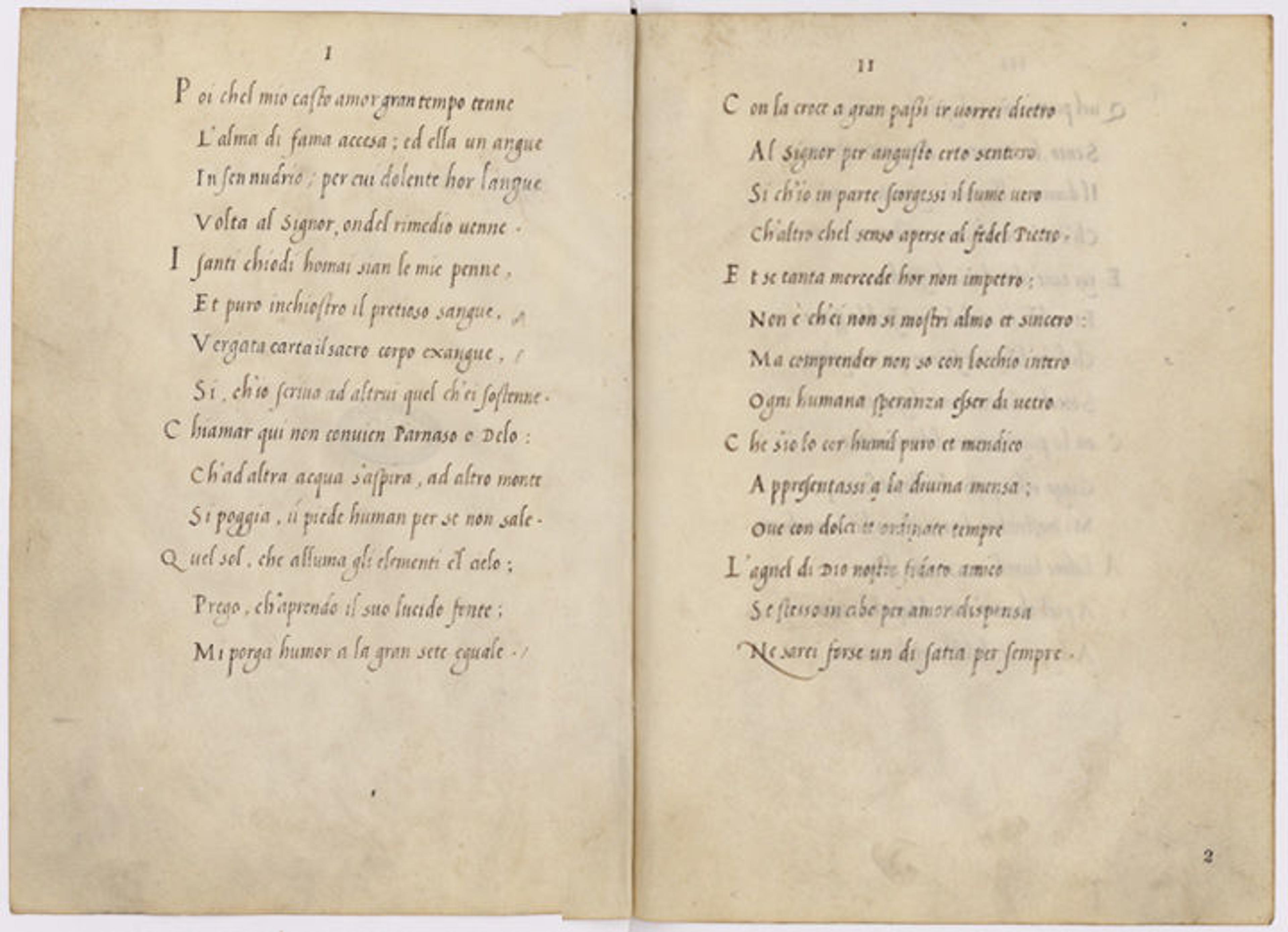

Vittoria Colonna (Italian, 1492–1547). Rime Spirituali (sonetti spirituali / della sig.ra Vittoria). Bound manuscript, opened to folios 1v-2r. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City (Cod. Vat. Lat. 11539)

Jeffrey Fraiman: As explored in the catalogue, around 1540 or so, Vittoria gave Michelangelo a small manuscript containing her poems, the Rime Spirituali—103 religious sonnets beautifully written in cursive by a professional scribe and bound within parchment covers. Viewers can see this object in the exhibition, on loan from the Vatican Library.

James Saslow: There was a good reason Michelangelo was so attracted to Vittoria, because she was a remarkable personality for that historical moment. The 16th century was the first time any significant number of female writers appear in Western Europe. Vittoria was the leading female poet of her time. No wonder Michelangelo admired her: She was doing something that had not been done by many women, and she was having considerable success.

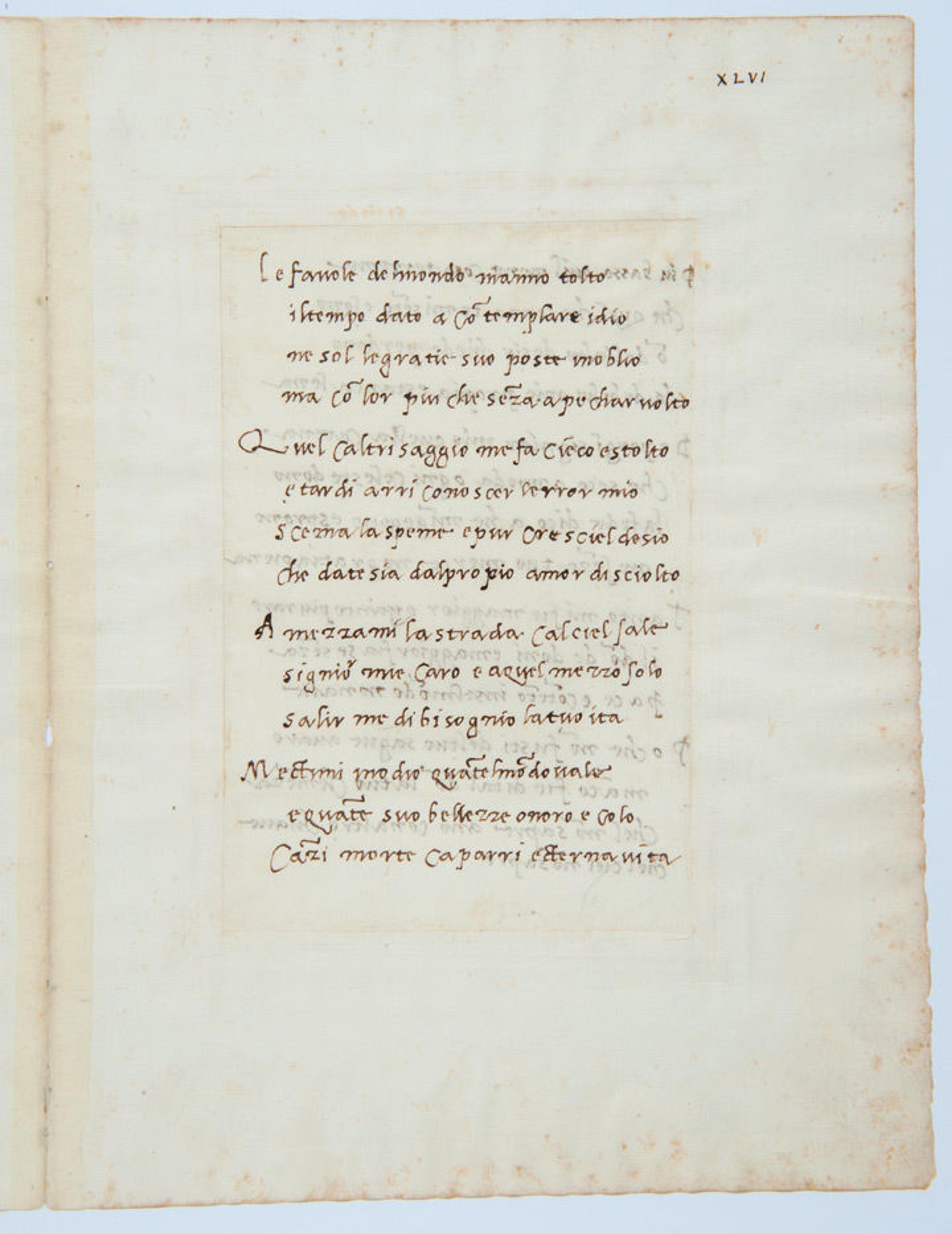

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475–1564). Sonnet, "Le favole del mondo," folio XLVI (recto). Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City (Cod. Vat. Lat. 3211). Read translation.

Jeffrey Fraiman: Next to the manuscript of Vittoria Colonna's poems, visitors can see one of Michelangelo's most famous poems, "Le favole del mondo," written some eight years after Vittoria passed away.

James Saslow: "Le favole del mondo" is one of the group of late poems where he renounces everything that was meaningful in his life up to that time. He is feeling the imminence of dying and being judged. These poems are all on this theme that everything that once was important to him now seems tempting and misleading, particularly love and art. He writes "the fables of the world," but he means all the false, alluring beauties of earthly existence—all that has robbed from him the time for contemplating God, which is the only thing he should be doing. "What makes others wise makes me blind and foolish" is a very sad line, because saying that everything he thought he was doing that was good turned out not to be, and his whole past life is a lie, or a mistake that he doesn't have enough time left to overcome.

Jeffrey Fraiman: In the catalogue, exhibition curator Carmen C. Bambach discusses in detail how the homoerotic, or homosexual, aspects of Michelangelo's art and biography have been either suppressed, censored, or played down through the centuries, and alternatively, the scholars who have brought these issues into the discussion, including you. Can you walk us through some of this history?

James Saslow: Everyone agrees that there is some element of homoerotic self-expression in both the poetry and the visual art, but attitudes about that have been ambivalent from the beginning. Some people in his day must have thought that his drawings of beautiful men indicated actual homosexual behavior, because he went out of his way to deny it. In Ascanio Condivi's biography, Michelangelo makes Condivi say that although some base-minded smutty people have accused him of sexual desire, he is only interested in beauty for its own sake.

Overt discussion of homoerotic elements in his work faded out after the 16th century because of censorship. His nephew Michelangelo the Younger published many of his poems in 1623. He knew that people would read the poems as homoerotic, so he changed many pronouns to make the verses heterosexual. He also changed phrases, omitted words, and, where he couldn't fully bowdlerize the poem, he would add brief annotations that provided a preferred allegorical reading that suggested the text was merely philosophical and not personal. So throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, there was not much awareness of that aspect of his work because it had been whitewashed.

Jeffrey Fraiman: When did scholars begin to acknowledge these homoerotic elements again?

James Saslow: Things began to change in the mid-19th century, when Victorian British historians became interested in resurrecting elements of homosexuality in Renaissance culture. Walter Pater (1839–1894) was one, the other was the critic John Addington Symonds (1840–1893). Symonds translated Michelangelo's poems into English, the first complete translation. What he did, which was radically important at the time, was to look at the original manuscripts and not to base his translations on Michelangelo the Younger's published versions. Symonds found the discrepancies and was determined to let people know what was really said.

Symonds's translations are really flowery, really Victorian. Even they gloss over passions that would have shocked his public too much, but he did introduce the body of evidence about Michelangelo's feelings for other men. A lot of people still didn't want to talk about it; they thought it was insulting to the memory of the great genius. More gay-friendly interpretations in modern terms didn't develop seriously until after the Stonewall Riots, when a significant number of art and literature historians were willing to deal with the subject frankly. It took that social revolution after Stonewall for scholars to say there was nothing inherently shameful about Michelangelo's passion; it was simply who he was.

Jeffrey Fraiman: What do you say to the naysayers who ask why we should care about Michelangelo's sexuality?

James Saslow: There are 60 poems out of 300 that are addressed to a man. It's the first significant modern corpus of love poetry from one man to another. Twenty percent is a significant portion of his work, which should have been dispassionately acknowledged long ago. It's true: Michelangelo didn't think of himself as a homosexual, mainly because he didn't have sex. Looking backward from our vantage point, though, he was a homosexual in the sense of someone whose primary physical and emotional desires were directed at somebody of the same sex.

So not only is it legitimate to think of Michelangelo as someone who felt homosexual passion, it's necessary to do that, because it's a significant part of his expression, and it sheds light on many of his works.

Sonnet, "Le favole del mondo"

Fables of the world

The fables of the world have robbed me of

the time allotted for contemplating God,

and not only have I disregarded his graces,

but have turned to sin more with them than without them.

What makes others wise makes me blind and foolish

and slow to recognize my own errors;

though hope is dimming, yet my desire increases

to be set free by you from my self-love.

Shorten by half the road that ascends to heaven,

my dear Lord, and I still will need your help

even to ascend just the remaining half.

Make me despise whatever the world treasures,

and all its beauties I honor and adore,

that I may, before death, secure eternal life.

(Translation by James M. Saslow)

Related Links

Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through February 12, 2018

Read more blog posts in this exhibition's Now at The Met series.

Purchase a copy of the catalogue in The Met Store.