Unidentified artist (after Yan Wengui [Chinese, 970–1030]). Buddhist Temples amid Autumn Mountains (detail), 14th century. Chinese, Yuan (1271–1368)–Ming (1368–1644) dynasty. Handscroll; ink and pale color on silk, overall with mounting, 13 1/8 in. x 37 ft. 2 1/8 in. (33.3 x 1133.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Dillon Fund Gift, 1983 (1983.12)

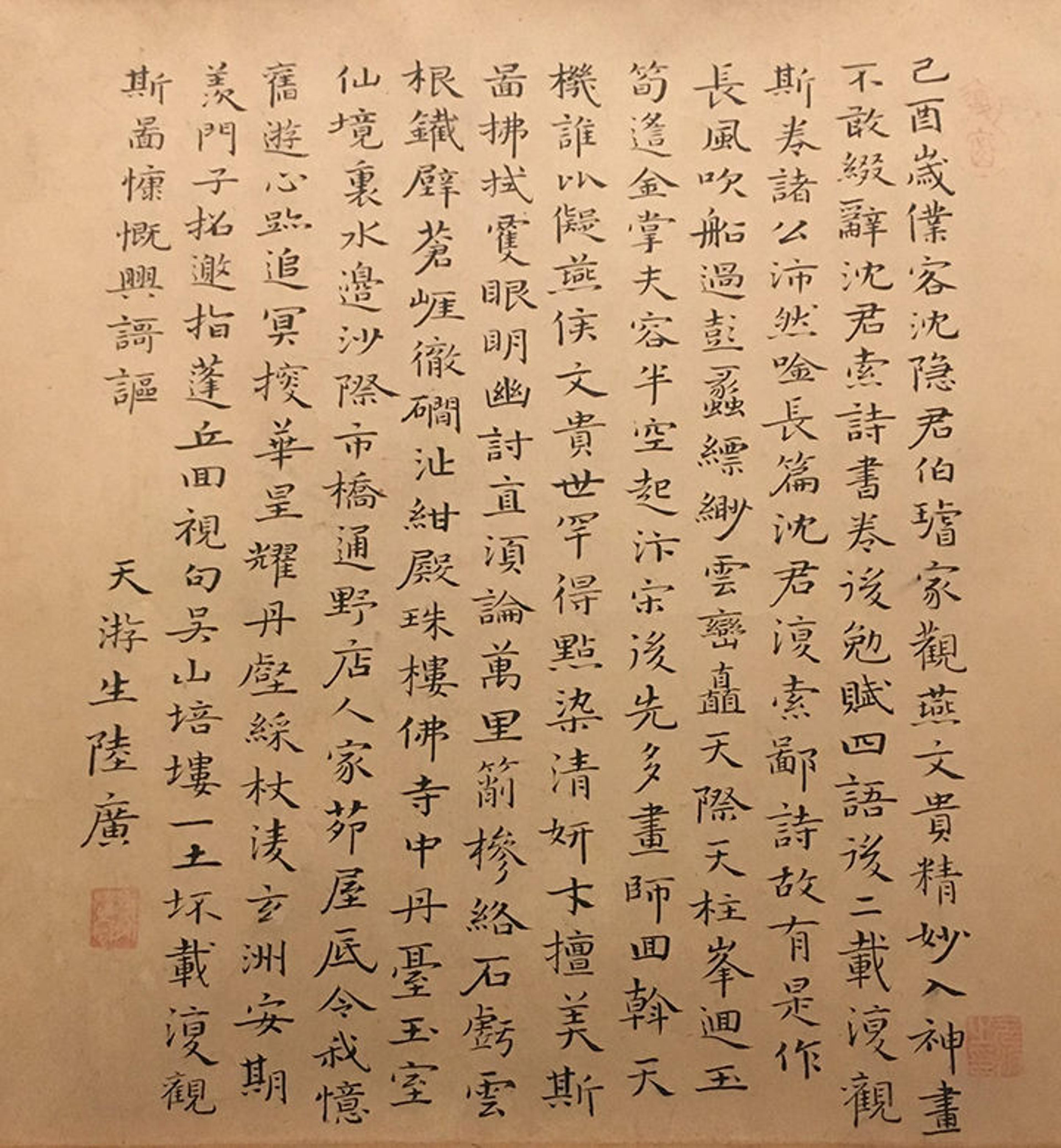

«Sometime in the fourteenth century, the Chinese poet and painter Lu Guang visited the home of Shen Boxuan, a "retired gentleman" (as Lu described him) and the owner of the handscroll pictured above, titled Buddhist Temples amid Autumn Mountains. When Shen presented the painting to Lu, the poet found himself "at a loss for words." Here was "a rare masterpiece," Lu later wrote, admitting that it took him "great effort" to compose the brief reflective poem on the painting that appends the work (called a colophon), which Shen urged him to write. Two years later, upon seeing the picture in Shen's home again, Lu found firmer footing. Inspired in part by the colophons written by other poets in the interim, he wrote a twelve-column meditation on the painting in a state of self-described "exhilaration." (All of Lu's remarks, like those of the other poets, are attached to the painting.)»

"Writing colophons is stressful for these guys," says Joseph Scheier-Dolberg, the Oscar Tang and Agnes Hsu-Tang Associate Curator of Asian art at The Met and the curator of the exhibition Streams and Mountains without End: Landscape Traditions of China, which features this painting in gallery 210. "They have to make up poetry on the spot and there are no re-dos." Some poets, such as Ni Zan, tried to make time for reflection before writing. When Ni visited Shen Boxuan and saw this painting in 1369, he wrote his poem after admiring the work "for a long time," as he wrote in his colophon.

Most of the time, Lu's and Ni's poems and the nine others that accompany this painting—all written in the fourteenth century—are not visible. This is because handscrolls such as these were not originally intended to be unfurled all at once. Instead, they were to be opened "one wingspan" at a time, Scheier-Dolberg says. "We are going on a journey" with paintings like these, he says, which is especially appropriate given this work's subject matter. As it opens, it reveals mountains, streams and waterfalls, a rocky landscape of trees, small clusters of travelers in boats, villagers outside their thatched-roof homes, isolated temples in the distance, and long expanses of untouched nature.

While certain areas of the painting are dense and layered, others, like this one, open into seeming infinity. Buddhist Temples amid Autumn Mountains (detail)

For Streams and Mountains without End, the handscroll has been opened almost fully, allowing visitors to see the entire painting and most of its colophons. Stylistically, the most striking aspect of the painting may be its curious spatial perspective. At points, the picture is densely packed with looming mountains and twisting waterfalls that truncate the space and bring everything directly to the foreground. At other places not too far away, large areas of water seem to open into infinity, beyond which the artist hints at mountains with faint atmospheric outlines.

Who made this work is an open question. For many years, it was believed to have been painted by Yan Wengui (Chinese, 970–1030), a Song-dynasty artist referred to in many of the colophons that accompany this picture. Yet modern scholars consider Yan's signature to be fake. The work is now described as a copy of a work by Yan and attributed to an unknown follower. The dating of the handscroll has also recently been altered. Once thought to be from the late twelfth to mid-thirteenth century, the Museum now considers it to be a fourteenth century work, and some of the colophons may have been written about other paintings, but later attached to this one as a way to increase its value. This practice was not uncommon in the premodern Chinese painting market.

Lu Guang's second colophon, from 1371, on Buddhist Temples amid Autumn Mountains

Questions of dating aside, the work has long been admired for its ability to quietly instill a sense of wonder. In 1771, more than three hundred years after the last fourteenth-century colophon was written, the Qing-dynasty Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1796) came into possession of this handscroll and offered his own reflection, written directly on the surface of the painting: "Hermit monks are elegantly unhurried / While travelers on their way are anxiously busy." This painting was a call to soothe those anxious travelers, the Emperor felt, adding that the artist behind this work "was revealing a truth to worldly people."