Jan van Eyck (Netherlandish, ca. 1390–1441) and Workshop Assistant. The Crucifixion; The Last Judgment, ca. 1440–41. Oil on canvas, transferred from wood, each: 22 1/4 x 7 2/3 in. (56.5 x 19.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1933 (33.92ab)

From Maryan Ainsworth, Curator in the Department of European Paintings:

Having made important discoveries about the originality of the newly uncovered texts on the frames of Jan van Eyck's Crucifixion and Last Judgment, and having come to crucial decisions about their restoration and preservation, it then was time to engage a paleographer to help us decipher these fragments of words and phrases. For this task, we approached an ace in this field: Marc Smith, professor of medieval and early modern paleography at the École Nationale des Chartes, and at the École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris.

Once the inscriptions on the frames of the Crucifixion and Last Judgment had been uncovered, the problem was far from solved. A few words were clearly legible—just enough to show that the text, in a formal Gothic minuscule, was a Middle Dutch translation of the Latin biblical inscriptions presented in pastiglia (the technique in which gesso is built up into three-dimensional forms) on all sides of both frames.

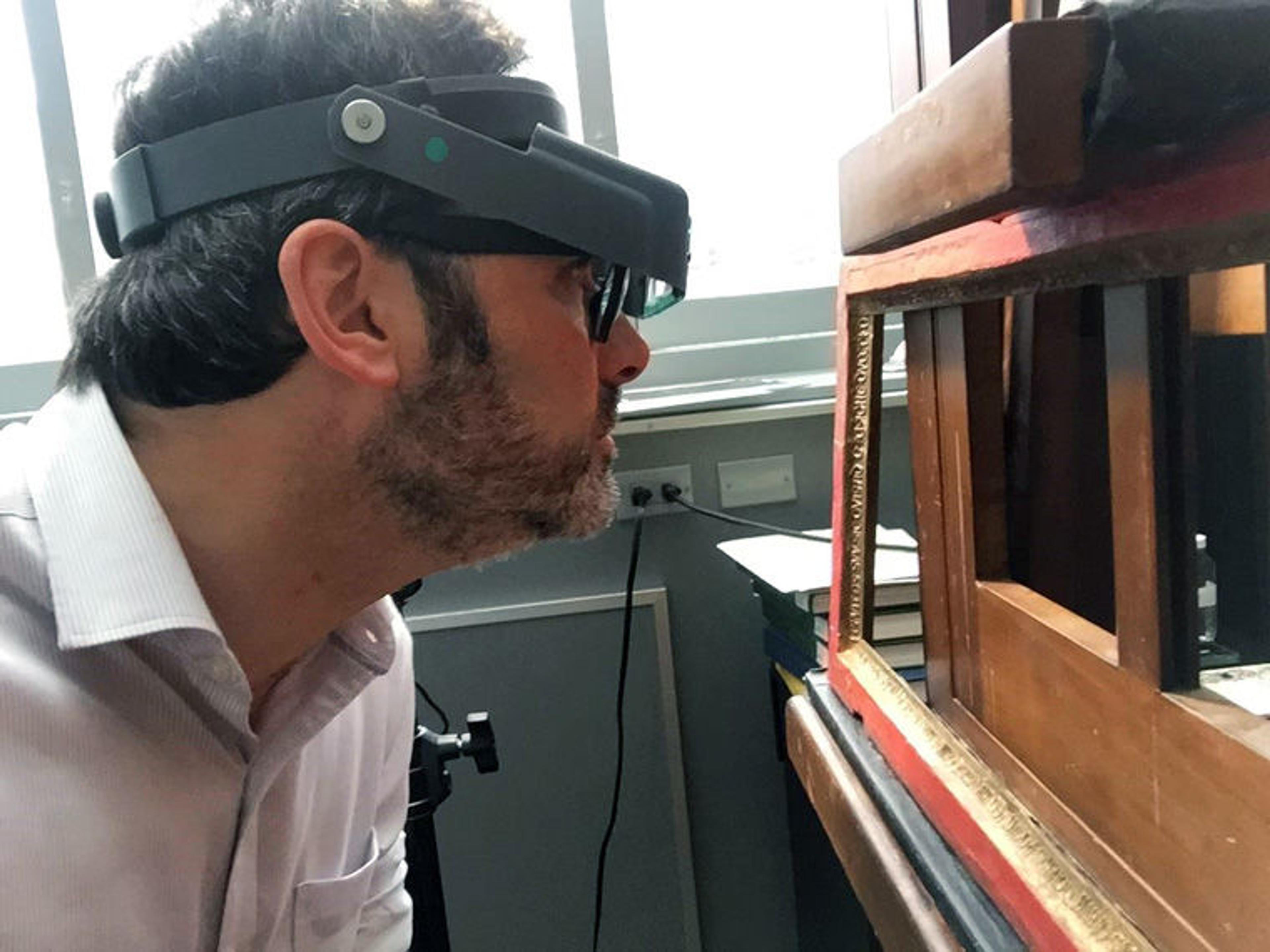

Since scholars of ancient and medieval writing, paleographers and epigraphers, are often confronted with scarcely legible letters but they seldom know what a texts says before reading it, the Van Eyck frames posed an unusual challenge to me. Reading the frames essentially meant establishing the correct wording and spelling as much as possible, in order to determine evidence of potential time and place of authorship. A reconstruction that could be one hundred percent certain was impossible: some parts of the text had been scraped off entirely; and on much of the surface only the tops of letters remained. The latter were often barely visible—specks of white or even ghosts of strokes (suggested by minimal color variations in the red paint underneath) that were visible only in high-resolution photographs or through a microscope.

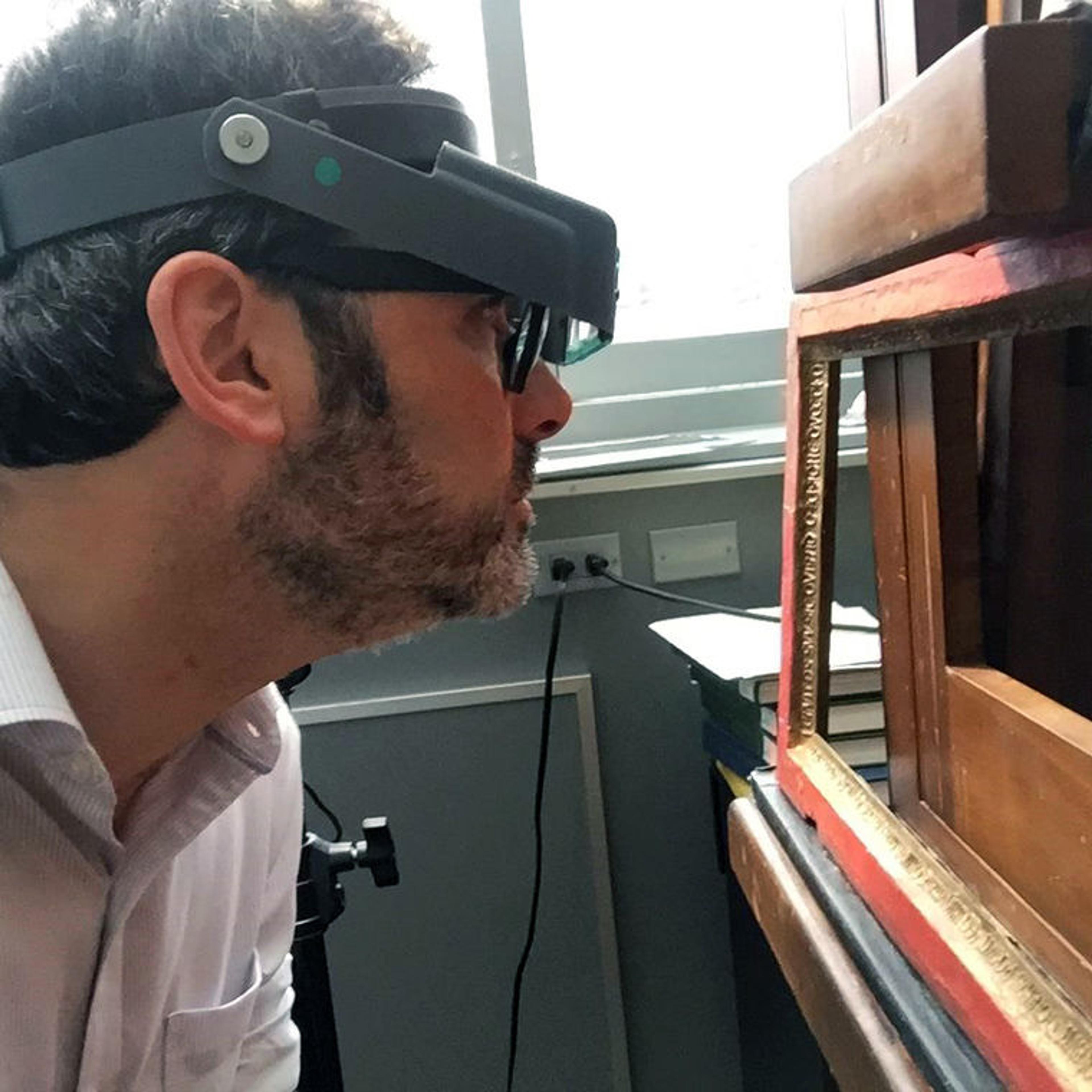

The author inspects the inscriptions on one of the frames. Photo by the author

Deciphering inscriptions—from unambiguous strokes to ambiguous scraps or total blanks—is very much a letter-by-letter, trial-and-error process, something like a crossword puzzle but with a larger meaning to develop. The fact that this was Gothic minuscule lettering helped quite a bit, since that script has a perfectly regular structure based on evenly spaced strokes resembling a garden fence with alternating pickets and spaces of uniform width, and the distinguishing features of each letter are located primarily at the top. This can make Gothic minuscule uncomfortable to read even under normal conditions, but allows for rigorous letter identification and reconstruction, especially if the upper part of the letter is preserved.

In overall appearance and in detail, the script is very similar to writing found not only on the Last Judgment panel, but also on other Van Eyck paintings and frames, just as the pastiglia inscriptions—in an archaizing majuscule script (all-capital letters) echoing Romanesque inscriptions—also resembles other Eyckian examples.

I tested hypothetical readings of every word by digitally overlaying photographs of the frames with text written in a Gothic typeface that was roughly similar to the original, especially in its spacing. Unlike drawing by hand, the constrained proportions of type resist any wishful thinking that would require condensing or extending letterforms. Fitting words into a given space relies on another means, the use of conventional medieval abbreviations, and enough of those are still visible on the frames to make further guesses possible. Any reconstructed letter needed to account for every visible trace of paint.

Detail view of a panel of the Crucifixion frame (top, in its cleaned state) and with the transcription in Gothic type digitally overlaid (bottom)

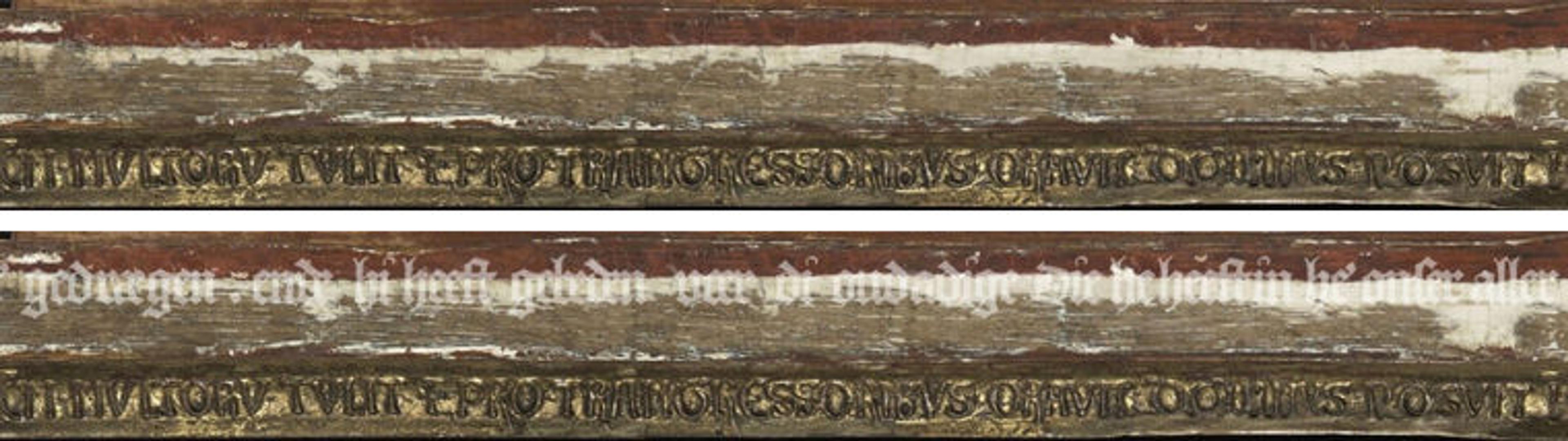

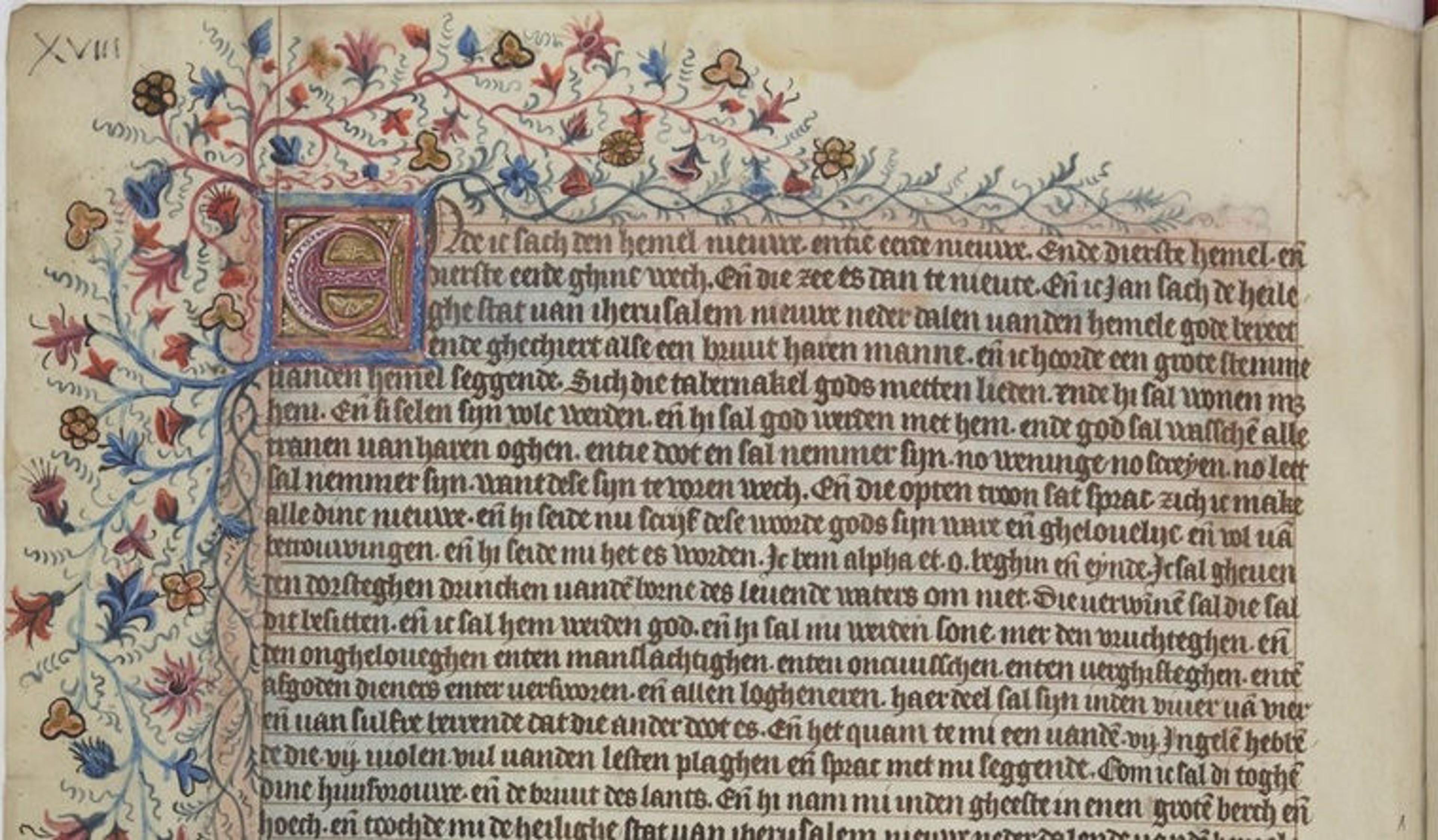

The task would have been easy enough if the quotations had been copied from an identifiable Middle Dutch translation. Unfortunately there was no standard translation of the Bible at the time, but a variety of partial versions that differed from one manuscript to the next—not to mention the biblical quotations that had been digested into other kinds of books, such as lay devotional literature. The spelling of the best-preserved parts of the frames points to a dialect from somewhere between the southern Netherlands and the German Rhineland, an area in which several important biblical translations were produced from the late fourteenth to the early sixteenth century. These suggested various ways in which the relevant passages could have been rendered.

Detail view of a page from the "Netherlandish Apocalypse," ca. 1400. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, ms. néerlandais 3, fol. 18 v°. Photo: BNF (Gallica)

Overall, it has been possible to reliably reconstruct almost three quarters of the total painted inscriptions—approximately five-sixths of the Crucifixion and half of the Last Judgment—with a few question marks remaining where alternative spellings or words are possible. (See below for translations.)

What can we learn from the text as it now stands? The Latin itself was not cleanly lifted from the Bible text (the Vulgate), but rehashed and adapted both to the iconography of the paintings and to the amount of space available, with the inscription of the Crucifixion starting top left, and that of the Last Judgment starting half-way up the left-hand side. It is quite noteworthy that this text begins with the words Ecce tabernaculum Dei, "Behold the tabernacle of God," which adds weight to the possibility that the panels were originally the doors of a tabernacle, as previously suggested by curator Maryan Ainsworth.

The translation fits the Latin so literally that it must have been composed especially for the frames, and both the script and the language confirm that this could have happened in the Van Eyck workshop, or not much later and not too far away. Was the commission switched from a pair of tabernacle doors to a devotional diptych for a layperson who would have wanted the text translated, shortly after or even before the panels were finished? Additional study, especially a comparison of these texts with other short Eyckian inscriptions in the vernacular (and even some notes scribbled in the hand of the artist himself), should tell us whether the dialect can be more accurately attributed to a specific geographic area and more definitively connected to Jan Van Eyck and his workshop.

Text Translation: The Crucifixion

And he gave up his soul in death . . . and he was numbered with the transgressors; and he bare the sin of many, and made intercession for the transgressors. The Lord hath laid on him the iniquity of us all. He was offered in sacrifice because he himself was willing. . . . he opened not his mouth: he is brought as a sheep to the slaughter, and as a lamb before her shearer was dumb, . . . For the transgression of my people have I stricken him. And he shall be given the wicked for his grave, and the rich for his death. [Isaiah 53:6–9, 12]

Text Translation: The Last Judgment

Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and he will dwell with them, and they shall be his people, and God himself shall be with them, and be their God. And he shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow... neither shall there be any more pain [Revelation 21:3, 4]

The sea gave up its dead [Revelation 20:13]

I will heap mischiefs upon them; I will spend mine arrows upon them. They shall be burnt with hunger, and devoured by birds with a most bitter bite . . . I will . . . send the teeth of beasts upon them, with the fury of creatures that trail upon the ground and of serpents [Deuteronomy 32:23, 24]

Death . . . gave up its dead . . . [Revelation 20:13]

The Crucifixion and The Last Judgment are on view at The Met Fifth Avenue in gallery 641.

Related Content

Read a selection of essays on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History that discuss topics related to this article: "Early Netherlandish Painting"; "Jan van Eyck (ca. 1390–1441)"; "Painting in Oil in the Low Countries and Its Spread to Southern Europe."

What's going on in The Met's Old Master galleries? View the web feature Met Masterpieces in a New Light to learn about the European Paintings Skylights Project, in which the skylights that admit natural overhead light into the galleries for optimal viewing of the collection will be replaced, in order to update and improve the quality of light in the galleries and resolve basic maintenance issues.