Cylinder seal and modern impression: hunting scene, ca. 2250–2150 B.C. Mesopotamia. Chert, H. 1 1/8 x Diam. 3/4 in. (2.8 x 1.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of W. Gedney Beatty, 1941 (41.160.192)

Did you know there are seals at The Met? No, not the animals you can visit at the zoo, but objects that are used to make a mark on another object. There are thousands of seals at the Museum from all over the world.

From left to right: Seal ring with inscription, late 15th–early 16th century. Attributed to Iran or Central Asia. Gold, cast and chased; nephrite, carved. H. 1 3/8 x Diam. 1 in. (3.5 x 2.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1912 (12.224.6). Seal, 14th century. French or Italian. Champlevé enamel, copper-gilt. 2 1/8 x 1 1/8 x 1 1/4 in. (5.2 x2.9x3.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.797). Jacob Boelen (ca. 1657–1729). Seal, ca. 1704. American. Silver, wood, 1 3/4 x 1 1/2 x 2 7/8 in. (4.3 x 3.8 x 7.3 cm); 1 oz. 11 dwt. (48.9 g). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of A. T. Clearwater, 1933; in cooperation with the Town of Marbletown, Ulster county, N.Y. (33.120.375)

The seals pictured above come from Central Asia, Europe, and Colonial America. Seals were made at different places and times and could be used to stamp important documents. Have you ever used a rubber ink stamp and an ink pad to make a design on a piece of paper? It's the same idea!

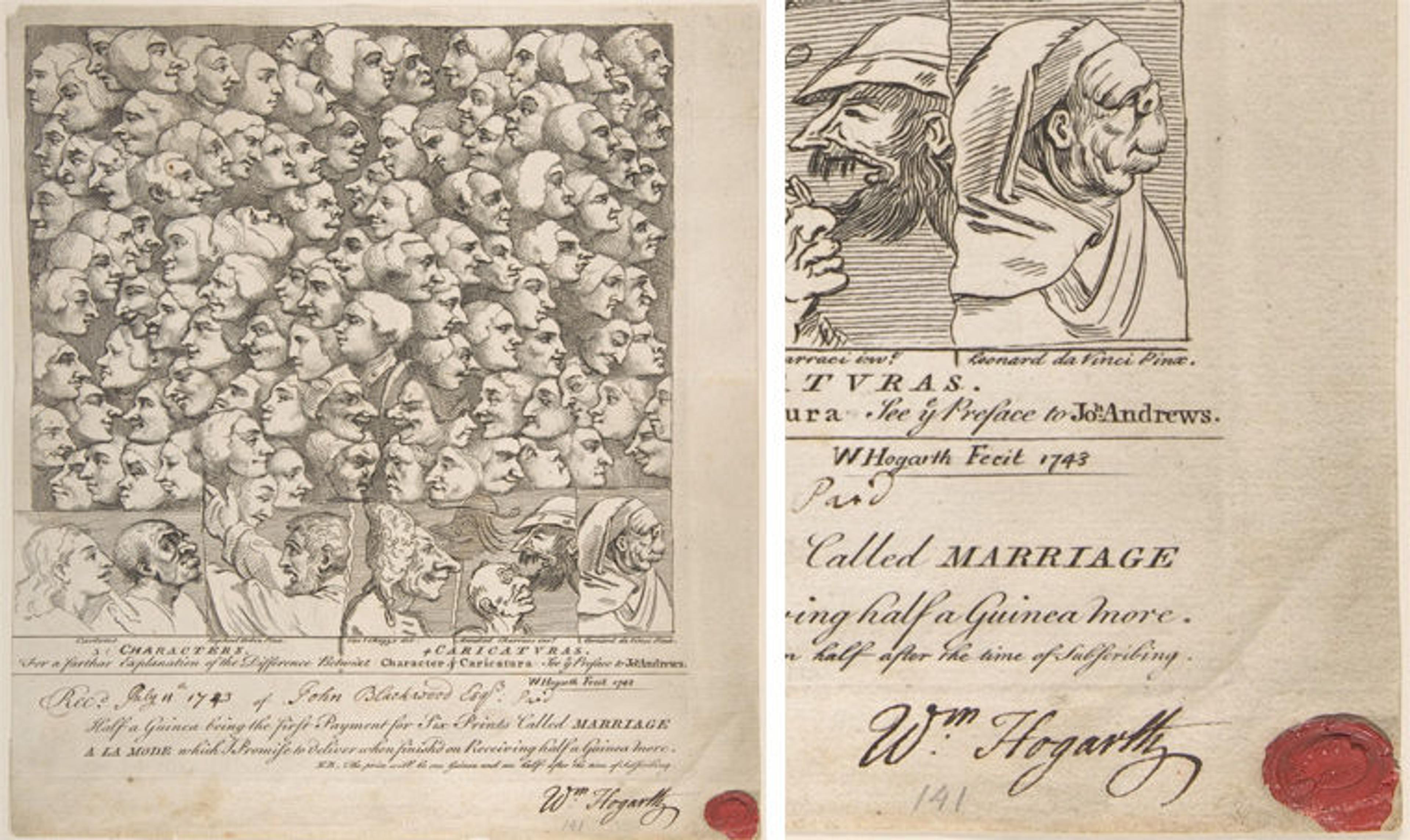

William Hogarth (British, 1697–1764). Characters and Caricaturas, April 1743. Etching, first state of two, sheet: 10 7/8 x 8 3/4 in. (27.7 x 22.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1932 (32.35(152)). Right: close-up of the lower right of the page that shows the signature and impressed wax seal of William Hogarth

A seal could be pressed into wax, leaving the image on the wax. Then the impressed wax could be attached to piece of paper. What do you notice about the impressed red wax on the print above? An image of an artist's palette and brushes is pressed into the wax.

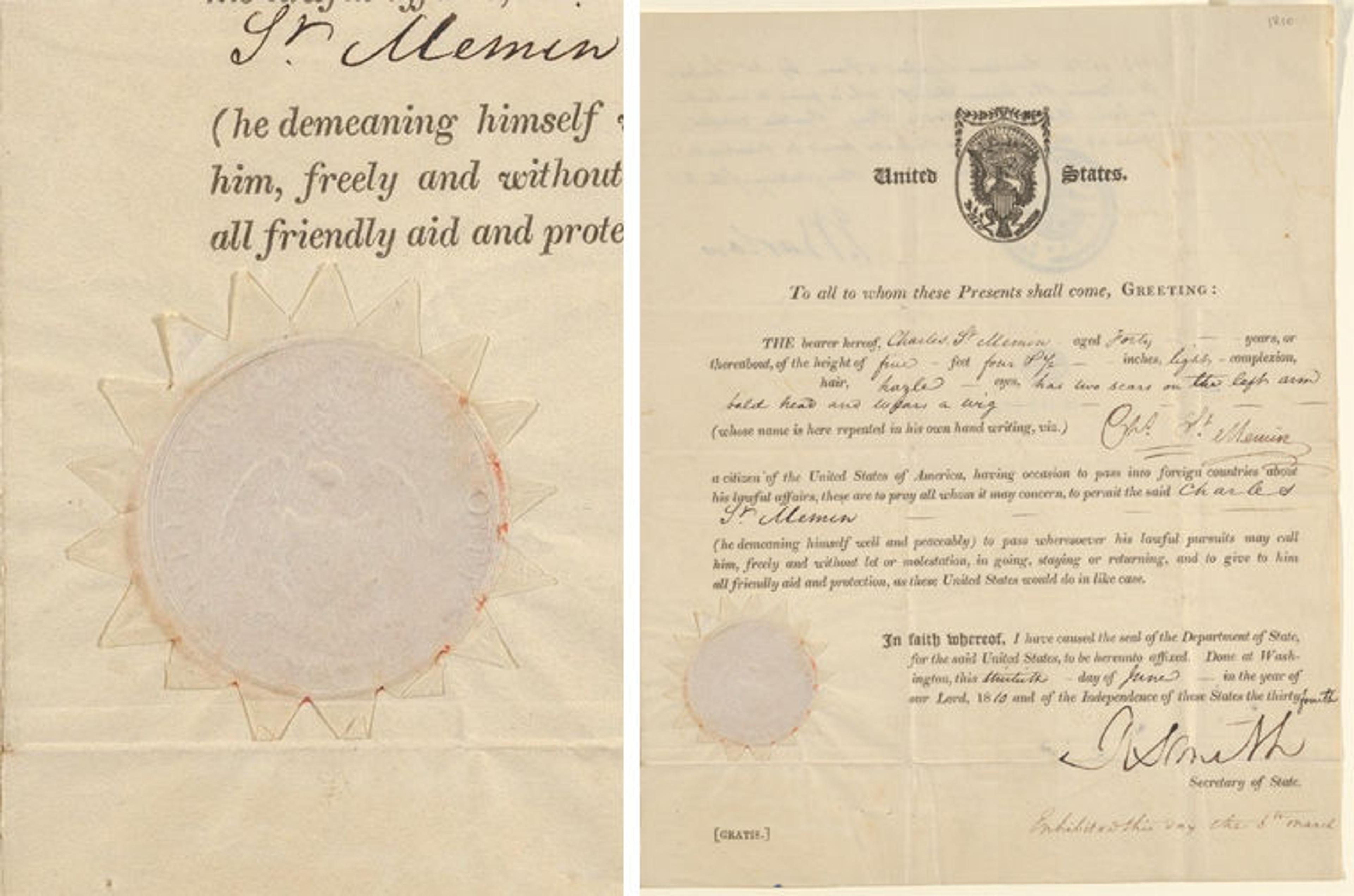

Right: The American passport issued to Charles de Saint-Mémin (French, 1770–1852) on June 30, 1810. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museum Accession (Ref.Saint-Memin.1). Left: Detail of the United States Department of State seal on the passport.

A seal could also be impressed on the paper itself. The page above is from an American passport from 1810. You can see a seal that looks like a sun, with an eagle in the center. It's an official government seal that was impressed on paper on top of wax.

From left to right: Cylinder seal: goddess leading a worshiper to a seated deity; bull god, ca. 20th–19th century B.C. Central Anatolia. Quartzite, H. 7/8 x Diam. 1/2 in. (2.21 x 1.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Raymond and Beverly Sackler Gift, 1991 (1991.368.3). Cylinder seal: male worshiper, dog surmounted by a standard, ca. mid-2nd millennium B.C. Mesopotamia. Carnelian, H. 1 x Diam. 3/8 in. (2.46 x 0.95 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of The Right Reverend Paul Moore Jr., 1985 (1985.357.44). Cylinder seal: Ishtar image and a worshiper below a canopy flanked by winged genies, ca. 8th–7th century B.C. Mesopotamia. Chalcedony, H. 1 1/4 x Diam. 1/2 in. (3.1 x 1.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Martin and Sarah Cherkasky, 1989 (1989.361.1)

Cylinder seals were invented thousands of years ago. The cylinder seal was a special kind of seal that could be rolled instead of stamped. For over 3,000 years, ancient people made and used them in the part of the world today called the Middle East.

Cylinder seal: battle of the gods, ca. 2350–2150 B.C. Iran, Luristan, Surkh Dum. Shell, H. 1 x Diam. 5/8 in. (2.5 x 1.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1943 (43.102.34) Right: View of the cylinder seal from below

So, what is a cylinder seal? As you might guess from the name, it's a cylindrical object. These cylinders were most frequently made of different types of stone. But they were also made from other materials like ivory, bone, and even shell. The cylinder seal above is carved into a piece of shell.

Cylinder seal and modern impression: male worshiper, dog surmounted by a standard, ca. mid-2nd millennium B.C. Mesopotamia. Carnelian, H. 1 x Diam. 3/8 in. (2.46 x 0.95 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of The Right Reverend Paul Moore Jr., 1985 (1985.357.44)

What makes these objects seals is that a design is carved into the surface of the cylinder. When the cylinder seal is pressed into and rolled on clay—as was done in ancient times—the design appears on the clay. The design appears in reverse! It's a bit like writing a note backwards and then reading it in a mirror. Today, experts at The Met create impressions of these ancient seals by rolling them on a modern material called Sculpey. You can buy it in an arts and crafts store. It's a lot like modeling clay.

Cylinder seal: winged horse with claws and horns, ca. 14th–13th century B.C. Northern Mesopotamia. Chalcedony, H. 1 3/8 x Diam. 1/2 in. (3.6 x 1.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Nanette B. Kelekian, in memory of Charles Dikran and Beatrice Kelekian, 1999 (1999.325.89). Right: Cylinder seal: seated "pigtailed ladies" and pots, ca. 3300–2900 B.C. Mesopotamia, Nippur. Limestone, H. 3/4 x Diam. 13/16 in. (1.9 x 2.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1962 (62.70.74)

Cylinder seals are some of the smallest works of art at The Met. They are often less than an inch tall, like the red one above. Some cylinder seals are a bit bigger. As you see here, they can also be thin or squat. There is no one exact size, but they are definitely miniature. When cylinder seals were created in the ancient world, tools for magnification—like microscopes or magnifying glasses—had not yet been invented. Imagine how hard it must have been to carve these tiny objects and into a round surface!

The first cylinder seals were probably made over 5,000 years ago. That's around the time that writing was invented. Cylinder seals had many different uses. They were often rolled on clay tablets and clay envelopes that had writing on them. The writing on these documents shows that different kinds of texts— like letters, receipts, and treaties— could be impressed with cylinder seals. The cylinder seal made a mark that functioned much like a signature.

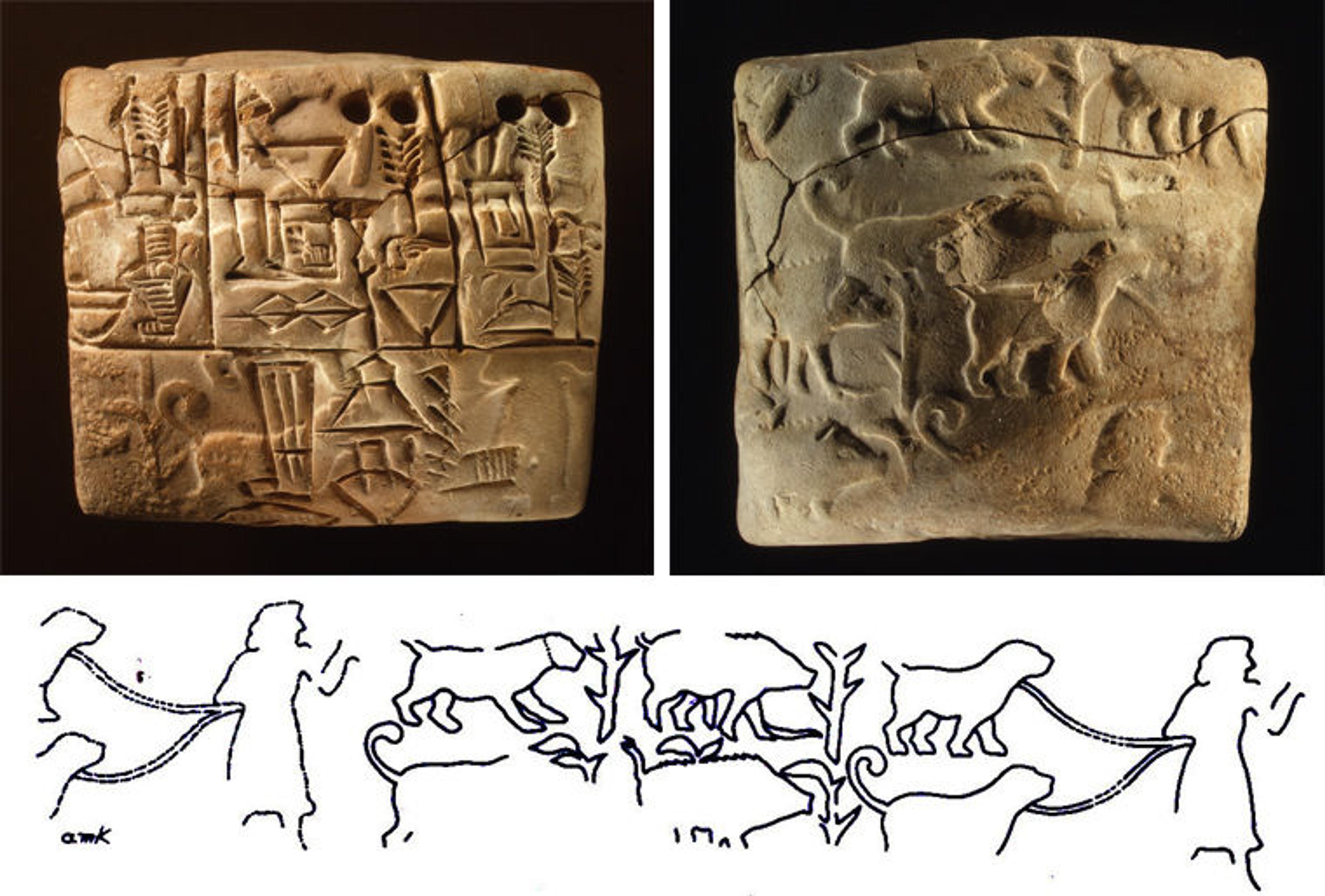

Here are two sides of a clay tablet. The tablet is small enough to hold in your hand.

Two sides of a proto-cuneiform tablet: administrative account of barley distribution with cylinder seal impression of a male figure, hunting dogs and boars, ca. 3100–2900 B.C. Mesopotamia, probably from Uruk (modern Warka). Clay, 2 1/8 x 3 3/8 x 1 5/8 in. (5.5 x 6 x 4.15 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Raymond and Beverly Sackler Gift, 1988 (1988.433.1). Bottom: Line drawing that shows the seal impression on this tablet. Illustration by Abdallah Kahil

The tablet has writing on it. You can see it in the photo on the left. It is an early form of cuneiform (wedge-shaped) script. The writing records amounts of grain. On the right, you can see images of animals made by a seal that was impressed multiple times on the clay tablet. The line drawing shows all the images that wrap around the tablet that were made by the one seal. You can see a male figure with hunting dogs and wild boars.

Not all clay tablets and envelopes were impressed with cylinder seals. But when they are, the design carved on the seal stands out on the clay like a raised relief. You can see how the design is raised on the clay envelope below.

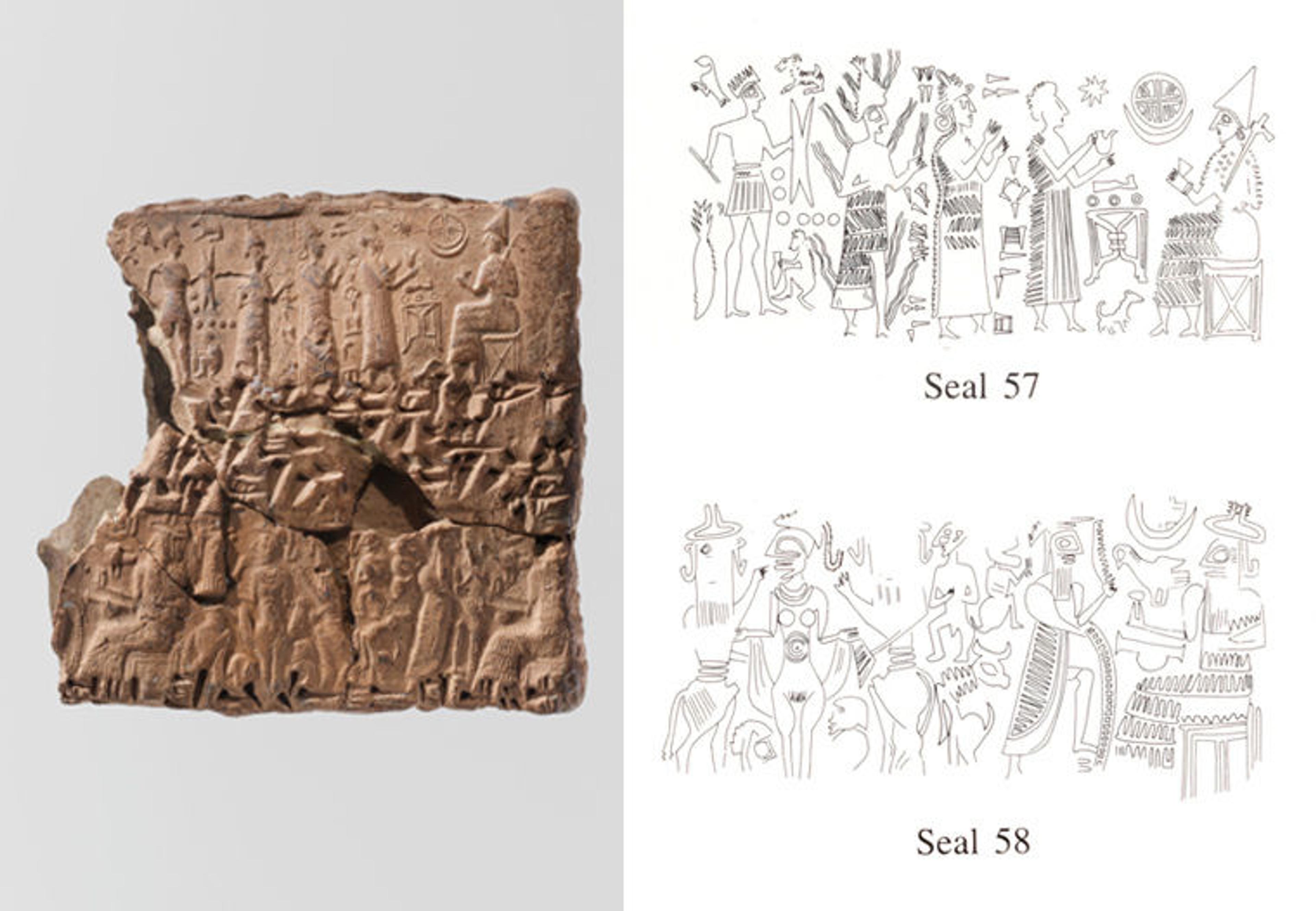

One side of a cuneiform case impressed with cylinder seals, ca. 20th–19th century B.C. Anatolia, probably from Kültepe (Karum Kanesh). Clay, 2 x 2 1/8 x 1 in. ( 5.2 x 5.4 x 2.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. J. Klejman, 1966 (66.245.16b). Upper right: Line drawing of a cylinder seal that shows a seated figure in a tall hat approached by four figures. Lower right: Line drawing of a cylinder seal that shows many figures including a seated god approached by a god holding a saw

This clay envelope once contained a clay tablet. The clay envelope has raised designs from two different cylinder seals that were pressed into the clay. The first line drawing (Seal 57) shows the design at the top of the clay envelope. You can see four figures approaching a seated figure wearing a tall hat. The second line drawing shows the design at the bottom of the clay envelope. You can see one god holding a saw in his hand. He is walking toward another god, who is seated. What other kinds of beings—like humans and animals—do you see in the designs made by the cylinder seals?

Sometimes when I tell people that I work with seals in the Museum, they think I am talking about the American Museum of Natural History. But now you know that The Met has seals and that cylinder seals aren't a separate animal species!

Visit #MetKids, a digital feature made for, with, and by kids! Discover fun facts about works of art, hop in our time machine, watch behind-the-scenes videos, and get ideas for your own creative projects.