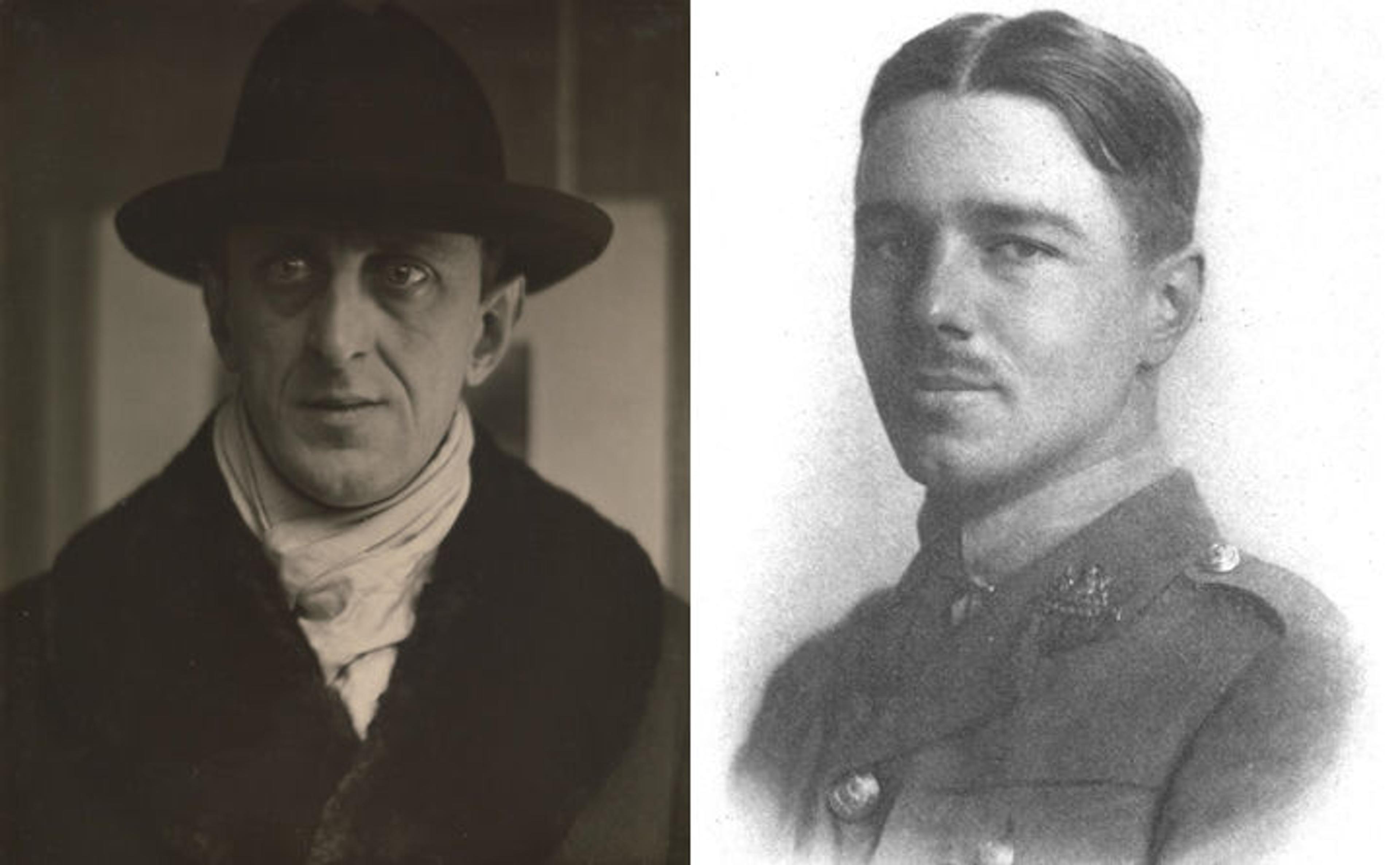

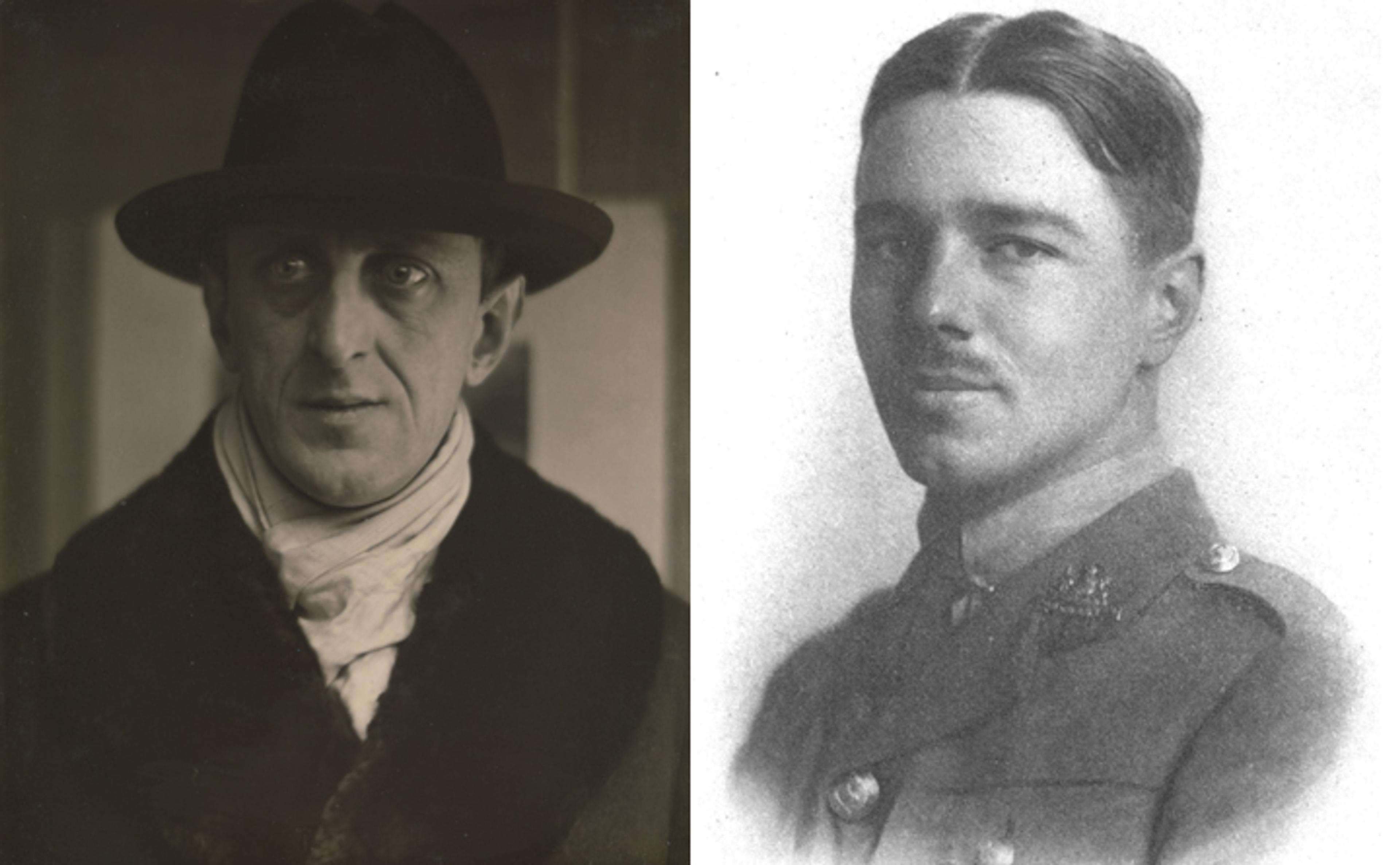

Left: Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864–1946). Marsden Hartley, 1916. Gelatin silver print, 24.8 x 19.8 cm (9 3/4 x 7 13/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Purchase, Gift of Marsden Hartley, by exchange, and Gift of Grace M. Mayer, by exchange, 2005 (2005.100.290). Right: Wilfred Owen, photographed in uniform in 1916. Photographer unknown; public-domain image via Wikimedia Commons

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

—Wilfred Owen

«It's difficult to overestimate the impact World War I had on European culture, as the first modern war prompted artists and writers to find new ways to represent life among the ruins. In addition to taking stock of how artists approached their practices as a result of the war, we can now, through a 21st-century lens, recontextualize and clarify the contributions of those who may not have been able to live their truest identities at the time, including queer artists at work in a time of great intolerance toward minority sexualities.

Two such artists, the American painter Marsden Hartley (1877–1943) and the English poet Wilfred Owen (1893–1918), sought to memorialize the effects of the war in different ways: Hartley—one of the artists featured in the current exhibition World War I and the Visual Arts—communicated his personal grief at losing the man he loved in combat early in the war, while Owen used poetry to rail against society's largest institutions and to mourn the ways humanity had inflicted such damage upon itself.»

Hartley: From Maine to Paris and Berlin

In 1909, after completing what he deemed his first mature paintings, Marsden Hartley gained the attention of the photographer-gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, who was at the forefront of introducing European modernism to the United States. Stieglitz took great interest in Hartley, introducing him to the work of Picasso, Matisse, and Cézanne, and exhibiting Hartley twice at his famed 291 gallery in New York, in 1909 and 1912. Stieglitz helped subsidize Hartley's move to Paris later in 1912, where he connected Hartley with Gertrude Stein and her circle of avant-garde writers and artists. It was also during this time that Hartley saw the liberalism of European sexuality first-hand, with open displays of queerness a part of the city's fabric.

Paris life didn't fulfill Hartley artistically or socially, with the artist noting in letters that he felt out of place as an American among the European titans he had come to know in Stein's circle. In veiled reference to his homosexuality, Hartley wrote to Stieglitz of a pain that "grows stronger instead of less and it leaves one nothing but the role of spectator in life watching life go by." However, during a trip in 1913 to Germany with his friend Arnold Rönnebeck, Hartley became enamored with German culture and especially the modernist metropolis of Berlin. Unlike his fellow artists in Paris, Hartley felt artistically connected with the mysticism of Der Blaue Reiter, particularly the work of Franz Marc and Wasily Kandinsky, both of whom he befriended. Hartley began to incorporate elements of German Expressionism and Cubism into his work during this period, developing a personal pictorial vocabulary that gave life to his depictions of the city and people around him.

Berlin not only brought Hartley a sense of creative belonging, but a society that was more welcoming of his queer identity. Although Paragraph 175 of the German criminal code—which deemed homosexual acts between males a crime—had been in place since 1871, the political authorities and police in Berlin had become knowingly tolerant in their treatment of homosexuality, with records indicating more than 40 gay clubs active during the 1910s.[1] This cosmopolitan approach to sexuality seemed to free Hartley of the isolation he felt, and through Rönnebeck he met Karl von Freyburg, with whom Hartley fell deeply in love.[2]

Owen: Poetry as Warning

Owen, who was 16 years younger than Hartley, was born into a working-class family near the Welsh border in the west of England. As a young adult, he became disillusioned with the Anglican Church and its inactivity in addressing the poverty rampant in his area of the country. Feeling repressed by his provincial, religious upbringing and his family's lack of funds for a college education, Owen spent three years (1912–15) in France as a language tutor—first at the Berlitz School of Languages in Bordeaux, and later in the private employment of a middle-class family. In 1915, with the war intensifying, Owen joined the Artists' Rifles Officers' Training Corps, and spent several months in London, where he was able to frequent the city's Poetry Bookshop and get to know the gay writers of the famed Bloomsbury Circle.

Whether it was due to his new literary connections—which included the poets Robert Graves and Siegfried Sassoon (whose poem "At Carnoy" served as the inspiration for a C.R.W. Nevinson drypoint, That Cursed Wood, included in The Met's exhibition)—or the shock of what awaited him on the front lines, Owen's writing progressed quickly from promising juvenilia to mature poetry that maintained an effortless sense of legato and Keatsian lyricism. In just under two years—from January 1917, when Owen was first deployed to the Western Front, to his death in November 1918 at the age of 25—Owen had a rush of intense creativity, writing bold, passionate poems that expressed great indignation for the institutions that fanned the flames of war. Owen noted: "Above all I am not concerned with poetry. My subject is war, and the pity of war. The poetry is in the pity. . . . All a poet can do today is warn."

For Owen, his warning cries memorialized a sense of loss not at the personal level, but at the larger level of humanity—a generation lost to the slaughter. In "Anthem for Doomed Youth," Owen comments on the futility of combat and the lack of respect afforded the fallen soldiers:

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles' rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

In elegant sonnet form, Owen composes a fiery judgment. The juxtaposition of military symbols—guns, rifles—and religious iconography—passing bells, prayers (orisons)—speaks to Owen's belief that religion is futile in confronting the horrors of war. Religion is not the provider of consolation here, but an institutional body that helped provoke the war in the first place, laying waste to the beauty that is humankind, an idea Owen deals with again in "Futility," one of only five poems published during his lifetime:

Was it for this the clay grew tall?

—O what made fatuous sunbeams toil

To break earth's sleep at all?

In just two simple questions of existential grandeur, Owen interrogates heaven and earth as to how man could reach such heights of intellectual thought and creativity, only to waste it all on vengeful arrogance, empty nationalism, and the machinations of death. As with many of his countrymen active in the visual arts who initially embraced—even fetishized—the modern technology of war through Vorticist and Futurist styles, but later came to reject it, Owen too condemned modern technology. This comes through most searingly in his "Sonnet on Seeing a Piece of Our Artillery Brought into Action," in which he confronts the irony of warfare being the only mechanism that can stop mankind's hubris:

Be slowly lifted up, thou long black arm,

Great gun towering towards heaven, about to curse;

Sway steep against them, and for years rehearse

Huge imprecations like a blasting charm!

Reach at that arrogance which needs thy harm,

And beat it down before its sins grow worse.

Initially, the poem seems to extol military might. But Owen makes his feelings about warfare quite clear in the poem's seething final lines:

But when thy spell be cast complete and whole,

May God curse thee, and cut thee from our soul!

Hartley's Brush with Nationalism

Marsden Hartley (American, 1877–1943). The Warriors, 1913. Oil on copper, 121.29 x 120.65 cm (47.75 x 47.5 in.). Private collection

Hartley, on the other hand, was at first taken with the pageantry of the German military. During the period before the war, Kaiser Wilhelm II orchestrated grand parades of martial units in full regalia as a display of his country's military might. In works like The Warriors of 1913, Hartley's enthusiasm for the ardent nationalism of the German people is clear, with majestic white steeds leading bands of soldiers upon delicate tufts of clouds. Absent from the work are the crowds of people taking part in the jubilant celebration; rather, the focus is on the soldiers in their dramatic white uniforms and their perfectly choreographed cortège. Here Hartley sexualizes the militarism of the German people, visualizing the connections between the cult of masculinity prevalent in the military and homosexual cultures of Wilhelmine Germany.[3]

Yet the devastation that spread across Europe after the outbreak of World War I quickly dampened the fires of nationalism and military hubris for many. Hartley's deepest personal loss occurred during the initial outbreak, when von Freyburg was killed in battle just three months after the conflict began. Grief-stricken, the artist did not retreat from Germany but instead focused his work on memorializing this loss—albeit in a very encoded way.

Marsden Hartley (American, 1877–1943). (Left to right): Military Symbols 1; Military Symbols 2; Military Symbols 3, 1914. Charcoal on paper, each: 24 1/4 x 18 1/4 in. (61.6 x 46.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1962 (62.15.1; 62.15.2; 62.15.3)

The three drawings of military symbols from The Met collection on view in World War I and the Visual Arts are considered preparatory studies for Hartley's War Motif series, a collection of 12 paintings that he completed between 1914 and 1915. In these works, the artist grappled with his love of von Freyburg and his romanticized view of the German military, transforming the icons he had triumphantly emblazoned in works like The Warriors into symbols of loss.

Left: Marsden Hartley (American, 1877–1943). Portrait of a German Officer, 1914. Oil on canvas, 68 1/4 x 41 3/8 in. (173.4 x 105.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949 (49.70.42)

Also in The Met collection, Portrait of a German Officer is the magnum opus of the War Motif series—a life-size memorial to von Freyburg painted in Hartley's unique mix of Cubist and German Expressionist styles. Present within the painting are numerous coded references to von Freyburg: the soldier's initials, "KvF"; "4," the military regiment in which he served; "24," the age at which he died; an Iron Cross, which he had been honored with shortly before his death; and a chessboard in reference to von Freyburg's favorite game. Also woven throughout the work are elements of the Bavarian flag, as well as the flags of England and Belgium, on which Germany had declared war months earlier.

Just as Portrait of a German Officer is coded with layers of meaning that Hartley could not otherwise communicate at a time of intolerance toward homosexuals, so too did he need to mask the intention of his German paintings upon his return to the United States in 1915. After being held up at the border for nearly a year, Hartley was finally able in 1916 to retrieve his War Motif series, which Stieglitz had agreed to exhibit at 291. Unfortunately for Hartley, paintings depicting Iron Crosses and other German military insignia were met with a chilling reception by New York audiences. In a statement prepared for the exhibition, Hartley placated audiences by saying: "There is no hidden symbolism whatsoever in them . . . Things under observation, just pictures any day, any hour. I have expressed only what I have seen. They are merely consultations of the eye . . . my notion of the purely pictorial."

Owen's Tragic End

Owen, unlike Hartley, had no place to retreat. After hospitalization in 1917 for shell shock and several months in 1918 spent in England performing limited service, Owen returned to the front lines of France in September 1918, hoping to transmit more of the war experience into poetry. Tragically, Owen was killed during a German attack while his regiment crossed the Sambre–Oise Canal on November 4—exactly one week before the signing of the armistice. His mother, Harriet, received the telegram notifying her of her son's death on Armistice Day, as the celebratory church bells pealed in Owen's hometown of Shrewsbury.

Mention of Owen's sexuality was removed from all of his personal papers and correspondence by his brother, Harold, who converted all instances of same-sex pronouns into those of the opposite sex (similar to what Michelangelo's grand-nephew did after the Renaissance artist's death). Yet the homosexual writers of his day who knew Owen and who survived the war confirmed his true identity. Not only is Owen now regarded as the finest war poet of the English language, his poetry also inspired generations of queer English artists to come.

In 1961, the composer Benjamin Britten was commissioned to write a memorial work to consecrate the new Coventry Cathedral, built to replace the original 14th-century structure bombed during World War II. Britten—who spent the majority of his life in a public relationship with the tenor Peter Pears—chose to interlace eight of Owen's poems with the traditional text of the Latin Requiem mass in his intensely moving War Requiem.[4] One generation later, the director Derek Jarman—an activist in the artistic community who railed against the conservatism of Margaret Thatcher's government and the horrors of the AIDS epidemic, to which he would ultimately succumb in 1994—made a silent film scored only by the War Requiem that included visual cues to the futility of war, the arrogant greed of governmental and religious organizations—and Owen's homosexuality.

Notes

[1] The role of Germany, and especially Berlin, in the gay-rights movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries is surprising to contemporary readers. This is due in large part to the Third Reich's expansion of Paragraph 175 in 1935, at which point tens of thousands of gay men were imprisoned and sent to concentration camps wearing the mark of the pink triangle. Throughout the Wilhelmine period and the Weimar Republic, though, Germany had become a bastion of sexual liberation, even coming close to decriminalizing homosexuality in fall 1929. The measure faltered largely due to a final vote that did not take place in the Reichstag because of the recent stock-market crash and ensuing financial collapse.

[2] Although there is much debate as to the extent that von Freyburg returned Hartley's affection, there is no doubting the desire and admiration the artist felt for the Prussian officer.

[3] The presence of homosexual activity in the German military was brought to the international stage by the Eulenburg Affair, in which two close allies of Kaiser Wilhelm II were court-martialed and put on trial for homosexual indecency from 1907 to 1909. The trials became a judicial circus, and no one was charged in the end. Although there is no evidence that Hartley knew the particulars of the affair, this scandal's legacy would have been prevalent during the artist's years in Berlin, as it contributed greatly to the shaping of the modern homosexual identity in Germany.

[4] In a display of the power of music to heal even the deepest of wounds, Britten chose the War Requiem's three vocal soloists to be representative of the countries most devastated by the Second World War: the English tenor Pears, the German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, and the Russian soprano Galina Vishnevskaya. The Soviet regime refused to grant Vishnevskaya a travel visa to participate in the premiere, so her part was performed by the English soprano Heather Harper; Vishnevskaya appears on the original recording of the work produced in 1963.

Resources

Kornhauser, Elizabeth Mankin. Marsden Hartley. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

Lewis, C. Day, ed. The Collected Poems of Wilfred Owen. New York: New Directions, 1963.

McDonnell, Patricia. "'Essentially Masculine': Marsden Hartley, Gay Identity, and the Wilhelmine German Military." Art Journal 56, no. 2 (Summer 1997): 62–68.

Voorhies, James Timothy, ed. My Dear Stieglitz: Letters of Marsden Hartley and Alfred Stieglitz, 1912–1915. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2002.

Weinberg, Jonathan. Speaking for Vice: Homosexuality in the Art of Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and the First American Avant-Garde. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

Related Links

World War I and the Visual Arts, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 7, 2018

Read more blog posts in this exhibition's Now at The Met series.