There are many ghosts in the machine.

Let us start with the two larger-than-life Beings atop pedestals in the inner niches, guarding the entrance to The Metropolitan Museum of Art on Fifth Avenue. Lee Bul’s sculptural giants seem to herald a super- (or post-) human future, but they also carry multiple histories of human pasts. Long Tail Halo: CTCS #1 and Long Tail Halo: CTCS #2 (both 2024) invoke well-known figures from the history of art: think the Winged Victory of Samothrace, classical Greco-Roman sculptures, Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) (1912), and Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913).

Left: Marble statue of a wounded Amazon, 1st–2nd century CE. Roman. Marble, H. 203.84 cm (80 1/4 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1932 (32.11.4). Right: Umberto Boccioni (Italian, 1882–1916). Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913, cast 1950. Bronze; 47 3/4 x 35 x 15 3/4 in. (121.3 x 88.9 x 40 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Lydia Winston Malbin, 1989 (1990.38.3)

Lee’s sculptures also recall, even as they reimagine, a history of representation of the female form—from ancient, silent caryatids who carried the weight of the world on their heads to Botticelli’s famed goddess on the half shell (“shell” being an etymological root for the word “niche”) and Manet’s boldly corporeal Olympia (1863).

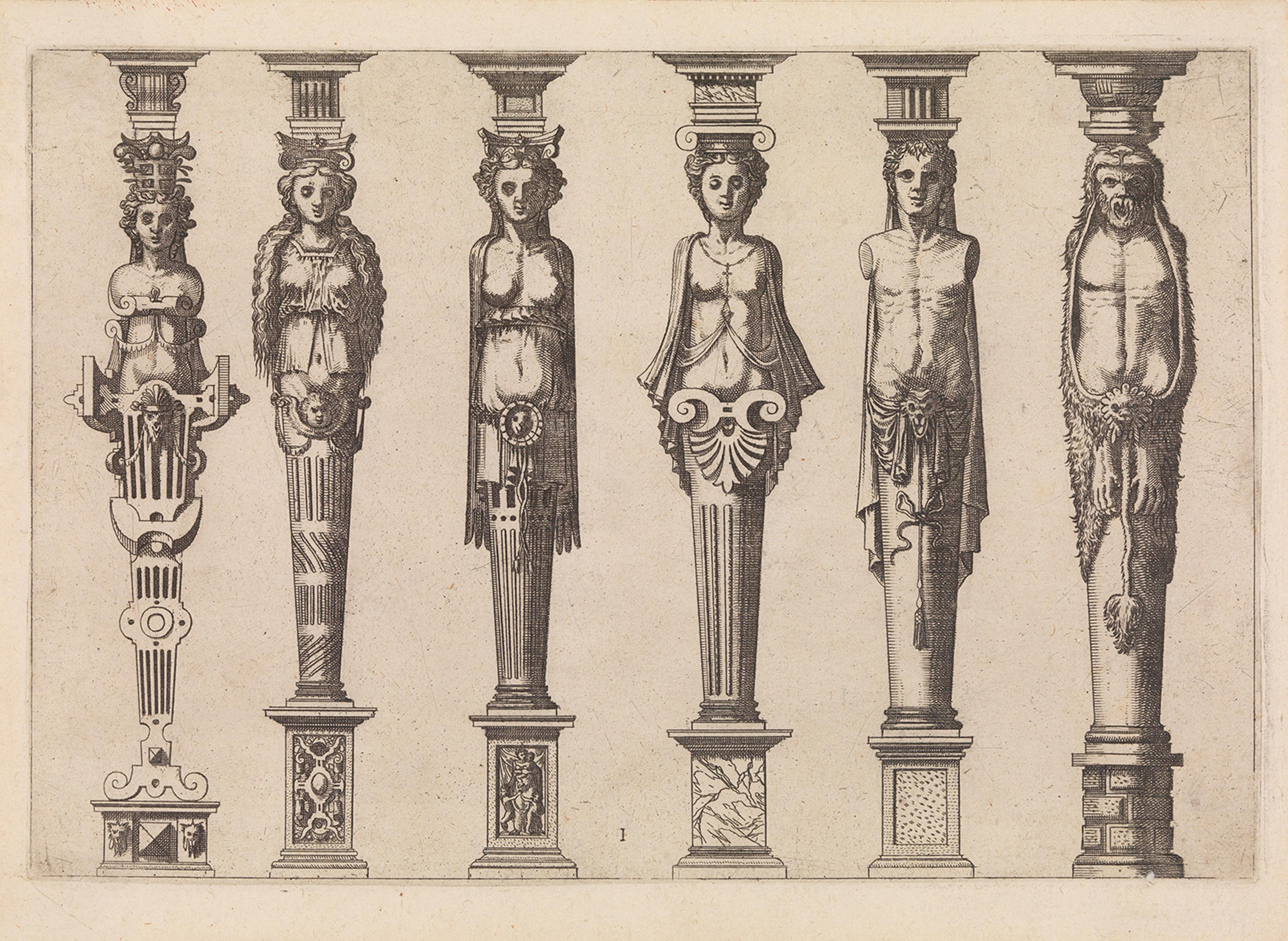

Various artists. Six terms, four female and two male, with Hercules at far right, ca. 1565. Etching 7 1/8 x 9 3/4 in. (18.1 x 24.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1966 (66.545.4[2])

But with CTCS #1 and 2, the traditionally exposed, naked, decorative, atavistic female body has grown structural, genderless, monumental, and heavy with ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) cladding. Instead of organic skin, we get the unfurling skein of polycarbonate surfaces. Instead of decoration, we get architecture. Instead of woman or man, we get an (in)human hybrid. Both figures appear to be on the verge of striding forward, yet they are firmly rooted in the present and the past. Indeed, they insist on the continuity, rather than separation, between ancient myth and modern science fiction, reminding us that our fantasies of the future are always rooted in our fictions of the past.

Left: Lee Bul (South Korean, b. 1964). Long Tail Halo: CTCS #1, 2024. Stainless steel, ethylene-vinyl acetate, carbon fiber, paint, polyurethane, 275(h) x 127(w) x 162(d) cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © Lee Bul. Courtesy of the Artist Right: Lee Bul (South Korean, b. 1964). Long Tail Halo: CTCS #2, 2024. Stainless steel, ethylene-vinyl acetate, carbon fiber, paint, polyurethane, 268(h) x 127(w) x 111(d) cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © Lee Bul. Courtesy of the Artist

If the museum has been increasingly criticized as a repository of imperial and colonial rapaciousness, then Lee’s sentinels remind us that the museum is also a space for critical remembrance, a crucial holder of the past and how that past continues to shape our present. This is one reason why The Met’s decision to fill these pedestals with commissions designed to speak to contemporary issues feels radical and bold, especially given the willful forgetfulness of our current moment.[1] The ghostly animations invoked by CTCS #1 and 2 remind us that well before the advent of twentieth-century cybernetic ideas about human alterity, there have been many less or other-than human persons in the history of Western imperialism and colonialism, the precarious (un)lives of those who have been instrumental to, yet excluded from, civilizational values.

Before the posthuman, there was the cyborg, that creature of organic and inorganic interface. Before the cyborg, there were the enslaved and the “coolies” meant to replace them, the latter having been literally called “a race of machines” that represented ideal, disposable labor because they were thought to be insensate to pain and capable of enduring mindless tedium.[2] And before the “coolie,” there was also the enduring figure of the objectified Asian Woman, whom Marco Polo in the thirteenth century confused with the ornaments that adorned her and whose fleshly presence has, in the centuries since, grown synonymous with—indeed, to have been replaced by—thingliness: a conflation with luxury goods and commodified objects, from porcelain to silk.

Left: James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903). Purple and Rose: The Lange Leizen of the Six Marks, 1864. Oil on canvas, 36 3/4 x 24 1/8 in. (93.3 x 61.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Johnson G. Johnson Collection, 1917, cat. 1112.

The Asiatic woman continues to be conflated with artificial life to this day. In science-fiction cinema from Blade Runner (1982) to Cloud Atlas (2012), she is the cyborg. But there are other gendered, racialized, and interstitial beings that predate and anticipate the dream of the cyborg. Consider the mermaid, another “in-between” creature who enmeshes the human and the inhuman. The fear of and fascination with the mermaid in many cultures since antiquity has much to do with deep-seated anxieties about interspecies encounters, worries that survive in modern-day eugenics and anti-miscegenation sentiments.

An etching of A mermaid, situated on a rock, 1814 by James Godby

There are many ghosts in the machine.

Who or what is considered human—and who or what is not—constitutes a dominant, ongoing project in Western civilization from the Age of Exploration to the present, a long durée that has produced a great deal of beauty, profit, and violence. The meeting of beauty and monstrosity, and the human stakes of that convergence, has preoccupied Lee through most of her career. In the 1990s, she was already thinking about the stakes of human-made-things and things-made-flesh.

Installation view of Lee Bul at Art Sonje Center, Seoul, 1998. © Lee Bul. Courtesy of the artist

Lee’s Anagram and Cyborg series dramatize the complicity between the organic and the inorganic. Crafted from materials often used for women’s ornaments—including metal, silicone, resin, chains, crystal beads, and organic matter—both meditate on the convergence between art and waste, beauty and monstrosity. We might think of these works as representing the two teleological endpoints of Asiatic femininity in the Western racial imaginary: the Anagram series, reminiscent of morphed monsters, represents perverse, organic excess, and the Cyborg series represents the distillation of synthetic and utilitarian beauty.

Like her current work, Lee’s earlier Anagrams and Cyborgs carry both history and an internal critique of that history. Smaller, partial-body sculptures from the Cyborg series, such as Untitled (cyborg leg) (2000), are visions of a future reality made of porcelain, a very old material harking back to the history of that precious “white gold,” one of the first objects of global trade and avarice, a history of beauty but also violence. Wars were waged in the name of that desire.

Lee Bul (South Korean, b. 1964). Untitled (cyborg leg), 2000. Porcelain, H. 21 in. (53.3 cm); W. 9 in. (22.9 cm); D. 14 in. (25.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Thaddaeus Ropac, 2023 (2023.285.1). © Lee Bul. Courtesy of the artist

The insistent bulkiness of this truncated, stranded, oversized foot also refutes the exotic fetishization of Asiatic women, a clichéd fantasy about feminine daintiness predicated on the reality of brutal deformity. Although Lee’s white Cyborgs look very different from the “Pink” and “Black” Anagrams at first glance—the former so immaculate while the latter oozes and undulates—we can detect how they might share an intimate genealogy.

Left: Lee Bul (South Korean, b. 1964). Cyborg W1, 1998. Cast silicone, polyurethane filling, paint pigment, 185 x 56 x 58 cm. © Lee Bul. Photo: Yoon Hyung-moon. Courtesy of the artist. Right: Lee Bul (South Korean, b. 1964). Monster: Pink, 2011 (reconstruction of 1998 work). Fabric, fiberfill, stainless-steel frame, acrylic paint, 210 x 210 x 180 cm. © Lee Bul. Photo: Jeon Byung-cheol. Courtesy of the artist

When it comes to the Cyborgs, one cannot help but note that these idealized figures are a mixture of precision and fragmentation, of power and fragility, of femininity and the inorganic. These android bodies are always presented as amputated, hung like meat on a hook; they are insistently un-useful. Embedded within their geometric beauty is both wreckage and refusal. The Anagrams, too, embody life and death: they appear grotesque, blobby, petrified, but they also exude a certain restlessness and vibrancy. Cyborg and monster are sisters in the history of human forms and their deformations.

Lee’s facade commission presents the next generation of the artist’s meditation on alternative life. If ornament has historically been considered a category of minor, feminine, and superfluous things, and nakedness considered primitive, female, and all-too-fleshly, then CTCS references and implodes both sets of assumptions. Art history has long insisted on an unassailable difference between the nude and the naked: the former consecrates ideal humanism, invoking the mind and the intellect, while the latter is seen as tied to the abject body and carries a host of related connotations about animality, femininity, and racial difference.

This segregation of the nude from the naked, codified by Kenneth Clark in 1956, has remained largely in place in art-historical studies.[3] Lee renders this distinction moot since the calm, inorganic surfaces of her guardians seem to be multiplying and unfolding, revealing not a “true” or single interiority but a series of form-generating surfaces. Interiority and exteriority challenge one another, just as structure and surface converge. If the distinction between the nude and the naked upholds philosophical stakes about value—enabling the contrast between the intellectual versus the merely decorative, the aesthetic versus the raw, parergon versus ergon—then Lee’s sculptures unsettle all of these differences. Such disruption can provoke thought and unease, because our apprehension in the face of that conflation says a lot about our discomfort with hybrid bodies and the ease with which we can be made to be strangers to others, as well as to ourselves.

Lee’s more-than-human and more-than-ornament creations integrate and expand the artist’s lifelong exploration of feminine themes into a profound reckoning with a history of representation about the human form, compelling us to rethink what constitutes the human in the first place.

Lee’s more-than-human and more-than-ornament creations integrate and expand the artist’s lifelong exploration of feminine themes into a profound reckoning with a history of representation about the human form, compelling us to rethink what constitutes the human in the first place. CTCS #1 and 2 (themselves handcrafted rather than machine-made) thus redraw the lost connection between modern technology and a much older notion of techne, from the Ancient Greek τέχνη, meaning art, craft, skill, or technique. They suggest that contemporary technology is profoundly indebted and tied to human labor, and to the making and unmaking of persons. By virtue of being both containers of vast historic memories and critiques of those pasts, CTCS #1 and 2 are alternately persons, monsters, cyborgs, shells, and gods. They insist on the grief of inhuman degradations and our need for the possibilities of transcendence.

Perhaps this is why it feels so uncanny to look at Lee’s monumental (in)human ornaments. Perhaps the sentinels invoke both the utopic (the post-gendered, the post-racial, the post-human) and the melancholic (their sensuality fragmented, multiplied, partial). There’s recognition and there’s refusal: CTCS # 1 and 2 look like they might be us, or some idealized form of us, but they also remain insistently other. They encase many ghosts, as crypts that we must surmise but cannot fully own. They register our ever-increasing entanglement with machinery, even as they seem not to need us at all. As Donna Haraway puts it, machines are uncanny because they can remind us of our own inertness. Walking under these giant sentinels—for we cannot approach them any other way given the scale—we are reminded of their secrets, their inaccessibility, even as they inspire our longing for something transcendent. Who or what counts—or does not count—as a person? What is the status of the human in the “Family of Man” when we face its inhumanity?

Left: Lee Bul (South Korean, b. 1964). Long Tail Halo: The Secret Sharer II, 2024. Stainless steel, polycarbonate, acrylic, polyurethane, dimensions variable Part A (top): 154(h) x 80(w) x 163(d) cm - Upper Part B (bottom): 217(h) x 95(w) x 245(d) cm - Lower. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © Lee Bul. Courtesy of the Artist Right: Lee Bul (South Korean, b. 1964). Long Tail Halo: The Secret Sharer III, 2024. Stainless steel, polycarbonate, acrylic, polyurethane, dimensions variable Part A (top): 154(h) x 80(w) x 163(d) cm - Upper Part B (bottom): 217(h) x 95(w) x 245(d) cm - Lower. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © Lee Bul. Courtesy of the Artist

As if to answer these searching questions, Lee offers the possibility of consolation in the face of our de-transcendence and loneliness: two companions for the guardians. In the outer niches, there are two dog-like creatures who are also larger than life, mythic, like some reimagined, divine Cerberi, named Secret Sharer II and III (both 2024).[4] Like their guardians, Secret Sharer II and III also hold the mystery and the silence of history. They, too, challenge us to rethink kinship and to question the connections among human, machine, and animal, between the material and the ineffable. Modeled after the artist’s own beloved pets, these companions stand hunched, flanking their wards, purging rains of glittering shards toward the steps of The Met. Again, waste and beauty, loss and birth. The distressing, gorgeous froth of crystalline fragments pours over the steps in an endless process of forming and deforming, a different order of life.

Notes

[1] The Met’s Fifth Avenue facade and building, designed by Richard Morris Hunt in 1902, originally featured four niches with pedestals that remained empty for 112 years, until 2019, when the museum initiated The Facade Commission for contemporary artists to fill these spaces. Lee Bul’s four sculptures for the Genesis Commission are the fifth installment in this series.

[2] In 1870, William M. Lawton, chair of the Committee on Chinese Immigrants for the South Carolina Agricultural and Mechanical Society, wrote: “I look upon the introduction of Chinese on our rice lands, and especially on the unhealthy cotton lands, as new and essential machine in the room of others that have been destroyed [or are] wearing out” (emphasis added), quoted by Gary Okihiro, Margins and Mainstreams: Asians in American History and Culture (1994).

[3] Kenneth Clark, The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form (1972). The holding power of this theoretical distinction is quite extraordinary, not only given the set of class, racial, and gender ideologies underlying Clark’s original formulation, but also because the nude has never been as easily disentangled from the naked as this overly efficient classification suggests.

[4] The two sculptures share their names with Joseph Conrad’s 1910 short story, a profound meditation on human loneliness.