MetPublications

Showing 1 – 10 results of 15

Sort By:

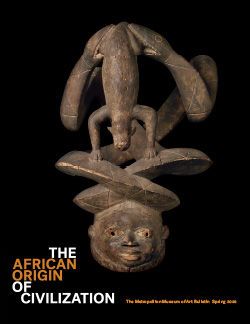

This Bulletin highlights five millennia of extraordinary artistic production on the African continent. Twenty-one pairings unite masterpieces from the Museum’s collections of ancient Egyptian and West and Central African art to reveal unexpected parallels and contrasts across time and cultures. The title pays special homage to Senegalese scholar and humanist Cheikh Anta Diop, whose book The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality (1974) challenged prevailing attitudes and advocated for recentering Africa as the source of humanity’s common ancestors and many widespread cultural practices. Building on Diop’s premise, this volume allows readers to delve into the rich histories and diverse artistic traditions from the cradle of human creativity.Download PDFFree to download

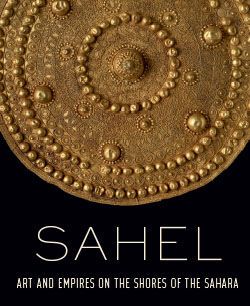

This Bulletin highlights five millennia of extraordinary artistic production on the African continent. Twenty-one pairings unite masterpieces from the Museum’s collections of ancient Egyptian and West and Central African art to reveal unexpected parallels and contrasts across time and cultures. The title pays special homage to Senegalese scholar and humanist Cheikh Anta Diop, whose book The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality (1974) challenged prevailing attitudes and advocated for recentering Africa as the source of humanity’s common ancestors and many widespread cultural practices. Building on Diop’s premise, this volume allows readers to delve into the rich histories and diverse artistic traditions from the cradle of human creativity.Download PDFFree to download This groundbreaking volume examines the extraordinary artistic and cultural traditions of the African region known as the western Sahel, a vast area on the southern edge of the Sahara desert that includes present-day Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, and Niger. This is the first book to present a comprehensive overview of the diverse cultural achievements and traditions of the region, spanning more than 1,300 years from the pre-Islamic period through the nineteenth century. It features some of the earliest extant art from sub-Saharan Africa as well as such iconic works as sculptures by the Dogon and Bamana peoples of Mali. Essays by leading international scholars discuss the art, architecture, archaeology, literature, philosophy, religion, and history of the Sahel, exploring the unique cultural landscape in which these ancient communities flourished. Richly illustrated and brilliantly argued, Sahel brings to life the enduring forms of expression created by the peoples who lived in this diverse crossroads of the world.

This groundbreaking volume examines the extraordinary artistic and cultural traditions of the African region known as the western Sahel, a vast area on the southern edge of the Sahara desert that includes present-day Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, and Niger. This is the first book to present a comprehensive overview of the diverse cultural achievements and traditions of the region, spanning more than 1,300 years from the pre-Islamic period through the nineteenth century. It features some of the earliest extant art from sub-Saharan Africa as well as such iconic works as sculptures by the Dogon and Bamana peoples of Mali. Essays by leading international scholars discuss the art, architecture, archaeology, literature, philosophy, religion, and history of the Sahel, exploring the unique cultural landscape in which these ancient communities flourished. Richly illustrated and brilliantly argued, Sahel brings to life the enduring forms of expression created by the peoples who lived in this diverse crossroads of the world. A fascinating account of the effects of turbulent history on one of Africa’s most storied kingdoms, Kongo: Power and Majesty presents over 170 works of art from the Kingdom of Kongo (an area that includes present-day Republic of Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Angola). The book covers 400 years of Kongolese culture, from the fifteenth century, when Portuguese, Dutch, and Italian merchants and missionaries brought Christianity to the region, to the nineteenth, when engagement with Europe had turned to colonial incursion and the kingdom dissolved under the pressures of displacement, civil war, and the devastation of the slave trade. The works of art—which range from depictions of European iconography rendered in powerful, indigenous forms to fearsome minkondi, or power figures—serve as an assertion of enduring majesty in the face of upheaval, and richly illustrate the book’s powerful thesis.

A fascinating account of the effects of turbulent history on one of Africa’s most storied kingdoms, Kongo: Power and Majesty presents over 170 works of art from the Kingdom of Kongo (an area that includes present-day Republic of Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Angola). The book covers 400 years of Kongolese culture, from the fifteenth century, when Portuguese, Dutch, and Italian merchants and missionaries brought Christianity to the region, to the nineteenth, when engagement with Europe had turned to colonial incursion and the kingdom dissolved under the pressures of displacement, civil war, and the devastation of the slave trade. The works of art—which range from depictions of European iconography rendered in powerful, indigenous forms to fearsome minkondi, or power figures—serve as an assertion of enduring majesty in the face of upheaval, and richly illustrate the book’s powerful thesis. Over the centuries, artists across sub-Saharan Africa have memorialized eminent figures in their societies using an astonishingly diverse repertoire of naturalistic and abstract sculptural idioms. Adopting complex aesthetic formulations, they idealized their subjects but also added specific details—such as emblems of rank, scarification patterns, and elaborate coiffures—in order to evoke the individuals represented. Imbued with the essence of their formidable subjects, these works played an essential role in reifying ties with important ancestors at critical moments of transition. Often their transfer from one generation to the next was a prerequisite for conferring legitimacy upon the leaders who followed. The arrival of Europeans as traders, then as colonizers, led to the dislocation of many of these sculptures from their original sites, as well as from the contexts in which they were conceived; thus, today they are seen primarily as timeless abstractions of generic archetypes. Heroic Africans reexamines the sculptures in terms of the individuals who inspired them and the cultural values that informed them, providing insight into the hidden meanings behind these great artistic achievements. Author Alisa LaGamma considers the landmark sculptural traditions of the kingdoms of Ife and Benin, both in Nigeria, Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire's Akan chiefdoms; the Bangwa and Kom chiefdoms of the Cameroon Grassfields; the Chokwe chiefdoms of Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (D.R.C.); and the D.R.C.'s Luluwa, Kuba, and Hemba chiefdoms. More than 140 masterpieces created between the 12th and the early 20th century—complemented by maps, drawings, and excavation and ceremonial photographs—reveal the religious and artistic conventions that defined these distinct regional genres.Download PDFFree to download

Over the centuries, artists across sub-Saharan Africa have memorialized eminent figures in their societies using an astonishingly diverse repertoire of naturalistic and abstract sculptural idioms. Adopting complex aesthetic formulations, they idealized their subjects but also added specific details—such as emblems of rank, scarification patterns, and elaborate coiffures—in order to evoke the individuals represented. Imbued with the essence of their formidable subjects, these works played an essential role in reifying ties with important ancestors at critical moments of transition. Often their transfer from one generation to the next was a prerequisite for conferring legitimacy upon the leaders who followed. The arrival of Europeans as traders, then as colonizers, led to the dislocation of many of these sculptures from their original sites, as well as from the contexts in which they were conceived; thus, today they are seen primarily as timeless abstractions of generic archetypes. Heroic Africans reexamines the sculptures in terms of the individuals who inspired them and the cultural values that informed them, providing insight into the hidden meanings behind these great artistic achievements. Author Alisa LaGamma considers the landmark sculptural traditions of the kingdoms of Ife and Benin, both in Nigeria, Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire's Akan chiefdoms; the Bangwa and Kom chiefdoms of the Cameroon Grassfields; the Chokwe chiefdoms of Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (D.R.C.); and the D.R.C.'s Luluwa, Kuba, and Hemba chiefdoms. More than 140 masterpieces created between the 12th and the early 20th century—complemented by maps, drawings, and excavation and ceremonial photographs—reveal the religious and artistic conventions that defined these distinct regional genres.Download PDFFree to download Textiles are a major form of aesthetic expression across Africa, and this book examines long-standing traditions together with recent creative developments. A variety of fine and venerable West African cloths are presented and discussed in terms of both artistry and technique. Wrapped around the body, fashioned into garments, or displayed as hangings, these magnificent textiles include bold strip weavings and intricately patterned indigo resist-dyed cloths. Also considered by the authors are striking contemporary works—in media as far-ranging as sculpture, painting, photography, video, and installation art—that draw inspiration from the forms and cultural significance of African textiles. This catalogue accompanies an exhibition held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, September 30, 2008–March 22, 2009.Download PDFFree to download

Textiles are a major form of aesthetic expression across Africa, and this book examines long-standing traditions together with recent creative developments. A variety of fine and venerable West African cloths are presented and discussed in terms of both artistry and technique. Wrapped around the body, fashioned into garments, or displayed as hangings, these magnificent textiles include bold strip weavings and intricately patterned indigo resist-dyed cloths. Also considered by the authors are striking contemporary works—in media as far-ranging as sculpture, painting, photography, video, and installation art—that draw inspiration from the forms and cultural significance of African textiles. This catalogue accompanies an exhibition held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, September 30, 2008–March 22, 2009.Download PDFFree to download Download PDFFree to download

Download PDFFree to download The rich and diverse artistic heritage of sub-Saharan Africa is presented in forty traditional works in the Metropolitan's collection. Included are a brief introduction and history of the continent, an explanation of the role of visual expression in Africa, descriptions of the form and function of the works, lesson plans, class activities, a map, comparisons, a bibliography, and a glossary. These educational materials are made possible by Mr. and Mrs. Marvin H. Schein.Download PDFFree to download

The rich and diverse artistic heritage of sub-Saharan Africa is presented in forty traditional works in the Metropolitan's collection. Included are a brief introduction and history of the continent, an explanation of the role of visual expression in Africa, descriptions of the form and function of the works, lesson plans, class activities, a map, comparisons, a bibliography, and a glossary. These educational materials are made possible by Mr. and Mrs. Marvin H. Schein.Download PDFFree to download Idealized pairings have been an enduring concern of sculptors across the African continent. This universal theme of duality is now examined in a handsome book that presents African sculptural masterpieces created in wood, bronze, terracotta, and beadwork from the twelfth to the twentieth centuries. Drawn from twenty-four sub-Saharan African cultures, including those of the Dogon, Lobi, Baule, Senufo, Yoruba, Chamba, Jukun, Songye, and Sakalava, the sculptures tell much about each culture's beliefs and social ideals. These artistic creations are astonishingly rich and diverse forms of expression. An essay written by Alisa LaGamma discusses thirty works, all of which are illustrated in colour. This book is the catalogue for an exhibition on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.Download PDFFree to download

Idealized pairings have been an enduring concern of sculptors across the African continent. This universal theme of duality is now examined in a handsome book that presents African sculptural masterpieces created in wood, bronze, terracotta, and beadwork from the twelfth to the twentieth centuries. Drawn from twenty-four sub-Saharan African cultures, including those of the Dogon, Lobi, Baule, Senufo, Yoruba, Chamba, Jukun, Songye, and Sakalava, the sculptures tell much about each culture's beliefs and social ideals. These artistic creations are astonishingly rich and diverse forms of expression. An essay written by Alisa LaGamma discusses thirty works, all of which are illustrated in colour. This book is the catalogue for an exhibition on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.Download PDFFree to download Since earliest human history, peoples around the globe have pondered their origins: Where do we come from? How did the world begin? In grappling with these fundamental questions, we developed a myriad of theories concerning our beginnings. "Every community in the world," according to historian Jan Vansina, "has a representation of the origin of the world, the creation of mankind, and the appearance of its own particular society and community." In many African cultures, these exalted ideas of "genesis" have been made tangible through rich expressive traditions interweaving oral history, poetry, and sculpture. This volume, which accompanies an exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, examines the staggering variety of ways in which African sculptors have given expression to social ideas of origin, from the genesis of humanity to the historical sources of families, kingdoms, agriculture, and other essential institutions. The seventy-five masterpieces presented here, drawn from public and private American collections, are among the most celebrated icons of African art, works that are superb artistic creations as well as expressions of a society's most profound conceptions about its beginnings. All are reproduced in color and are accompanied by entries that illuminate the distinctive cultural contexts that inspired their creation and informed their appreciation. Part I surveys a broad spectrum of African sculpture from across the continent and in a range of media. The Senufo peoples of Côte d'lvoire and Mali, for example, commemorate divine creation with large-scale carved wood figural pairs representing the primordial couple, the first man and woman. Among the Yoruba of Nigeria, the notion that humanity was modeled from clay at the beginning of time is evoked by sublime, antique terracotta busts. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a triptych of lavishly appointed, beaded masquerades reenacts a story of original sin and the source of Kuba kingship. The common desire to memorialize and exalt founding ancestors is reflected in numerous works, from boldly abstract zoomorphic masks from Burkina Faso to idealized figurative forms made across central Africa. Part II focuses on Africa's best-known sculptural genre, the ci wara headdresses of the Bamana peoples of Mali. The headdresses take their name from the mythological hero Ci Wara, who introduced the art of agriculture and an understanding of the earth, plants, and animals to the Bamana. To commemorate this vital contribution to human sustenance, the Bamana instituted a tradition of ceremonial dances in which Ci Wara was represented by costumes crowned with intricately carved wood headdresses. These sculptural elements have long been admired in the West for their elegant refinement and inventive abstraction. They often integrate the features of symbolic animals—possibly the antelope, aardvark, and pangolin—into graceful, endlessly dynamic designs. In her introductory essay, Alisa LaGamma considers the ci wara tradition in all its nuanced complexity and reveals some of the less well known regional and individual interpretations of the genre. She also provides an art historical overview of the theme of "genesis" and suggests ways of understanding African artistry from this perspective.Download PDFFree to download

Since earliest human history, peoples around the globe have pondered their origins: Where do we come from? How did the world begin? In grappling with these fundamental questions, we developed a myriad of theories concerning our beginnings. "Every community in the world," according to historian Jan Vansina, "has a representation of the origin of the world, the creation of mankind, and the appearance of its own particular society and community." In many African cultures, these exalted ideas of "genesis" have been made tangible through rich expressive traditions interweaving oral history, poetry, and sculpture. This volume, which accompanies an exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, examines the staggering variety of ways in which African sculptors have given expression to social ideas of origin, from the genesis of humanity to the historical sources of families, kingdoms, agriculture, and other essential institutions. The seventy-five masterpieces presented here, drawn from public and private American collections, are among the most celebrated icons of African art, works that are superb artistic creations as well as expressions of a society's most profound conceptions about its beginnings. All are reproduced in color and are accompanied by entries that illuminate the distinctive cultural contexts that inspired their creation and informed their appreciation. Part I surveys a broad spectrum of African sculpture from across the continent and in a range of media. The Senufo peoples of Côte d'lvoire and Mali, for example, commemorate divine creation with large-scale carved wood figural pairs representing the primordial couple, the first man and woman. Among the Yoruba of Nigeria, the notion that humanity was modeled from clay at the beginning of time is evoked by sublime, antique terracotta busts. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a triptych of lavishly appointed, beaded masquerades reenacts a story of original sin and the source of Kuba kingship. The common desire to memorialize and exalt founding ancestors is reflected in numerous works, from boldly abstract zoomorphic masks from Burkina Faso to idealized figurative forms made across central Africa. Part II focuses on Africa's best-known sculptural genre, the ci wara headdresses of the Bamana peoples of Mali. The headdresses take their name from the mythological hero Ci Wara, who introduced the art of agriculture and an understanding of the earth, plants, and animals to the Bamana. To commemorate this vital contribution to human sustenance, the Bamana instituted a tradition of ceremonial dances in which Ci Wara was represented by costumes crowned with intricately carved wood headdresses. These sculptural elements have long been admired in the West for their elegant refinement and inventive abstraction. They often integrate the features of symbolic animals—possibly the antelope, aardvark, and pangolin—into graceful, endlessly dynamic designs. In her introductory essay, Alisa LaGamma considers the ci wara tradition in all its nuanced complexity and reveals some of the less well known regional and individual interpretations of the genre. She also provides an art historical overview of the theme of "genesis" and suggests ways of understanding African artistry from this perspective.Download PDFFree to download This Closer Look focuses on a single work from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, a sculpture of a seated couple created by the Dogon people of Mali in West Africa. The goal is to inspire young people and adults to look more closely at works of art—to discover that details can be fascinating and often essential to understanding the meaning of a work of art. This packet may be used as an introduction to looking at and interpreting the Dogon couple, or as a springboard for exploring how it reflects the culture in which it was made. Teachers and students can use these materials in the classroom, but we know that study and preparation are best rewarded by a visit to the Museum.Download PDFFree to download

This Closer Look focuses on a single work from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, a sculpture of a seated couple created by the Dogon people of Mali in West Africa. The goal is to inspire young people and adults to look more closely at works of art—to discover that details can be fascinating and often essential to understanding the meaning of a work of art. This packet may be used as an introduction to looking at and interpreting the Dogon couple, or as a springboard for exploring how it reflects the culture in which it was made. Teachers and students can use these materials in the classroom, but we know that study and preparation are best rewarded by a visit to the Museum.Download PDFFree to download