If you believe, as Nina Simone believes, that “an artist’s duty is to reflect the times,” then you cannot encounter John Wilson's or Jason Reynolds's work and leave unchanged. Wilson, a renowned visual artist, and Reynolds, a celebrated author, both explore intimate and vulnerable worlds, with a particular investment in children’s and young adult literature. As an educator for The Met’s teen programs, I know the power of representation through imagery and words that Wilson and Reynolds promote for young readers.

On the occasion of the exhibition Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson, I sat down with Jason Reynolds to discuss Wilson’s career as an artist who also illustrated children’s books, the importance of displaying the nuances of Black life in literature and art, and Reynolds’s own career. Wilson and Reynolds share an understanding of the harsh realities of the past and present, but attempt to reconcile that for future generations through our shared humanity.

Jeary Payne:

Could you introduce yourself? What do I need to know to understand you?

Jason Reynolds:

I’m Jason Reynolds, proud son of Isabell and Allen, and to understand me, you need to know that despite my accomplishments as a writer, I’ll always just be Isabell and Allen’s son. That’s important to me. It’s because of them that I understand and value possibility. And grace. And courage. And fortitude. And imagination.

Gallery view of children’s books in Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson

Payne:

Our exhibition on John Wilson features more than one hundred works, many never before shown, spanning six decades. There is a section that focuses on his illustrations for children’s books, which I had never seen or heard of until the show, and it features these stunning images of Black children. Books like Mildred Taylor's Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry (1976) and The Gold Cadillac (1987) had an enormous impact on me as a young person, since I had not seen that kind of representation on the page before. Can you talk about that inciting event or encounter with a piece of Black literature that left a lasting impression on you?

Reynolds:

You know, I always wish I had an answer to this question that could be contextualized around my childhood, as you’ve referenced Mildred Taylor. But the truth is, I didn’t really begin my journey as a reader until I was seventeen. Not because I couldn’t read, but because the stories I needed either didn’t exist or weren’t accessible to me. At seventeen, though, I was handed Richard Wright’s Black Boy (1945) and was hooked, not because the subject matter was any different than the books foisted on me in school before, but because by page three, young Richard had set his grandmother's house on fire. It was the boredom—or what I perceived to be boredom—from the other novels that I was allergic to. Wright showed me that reading could be both edifying and entertaining.

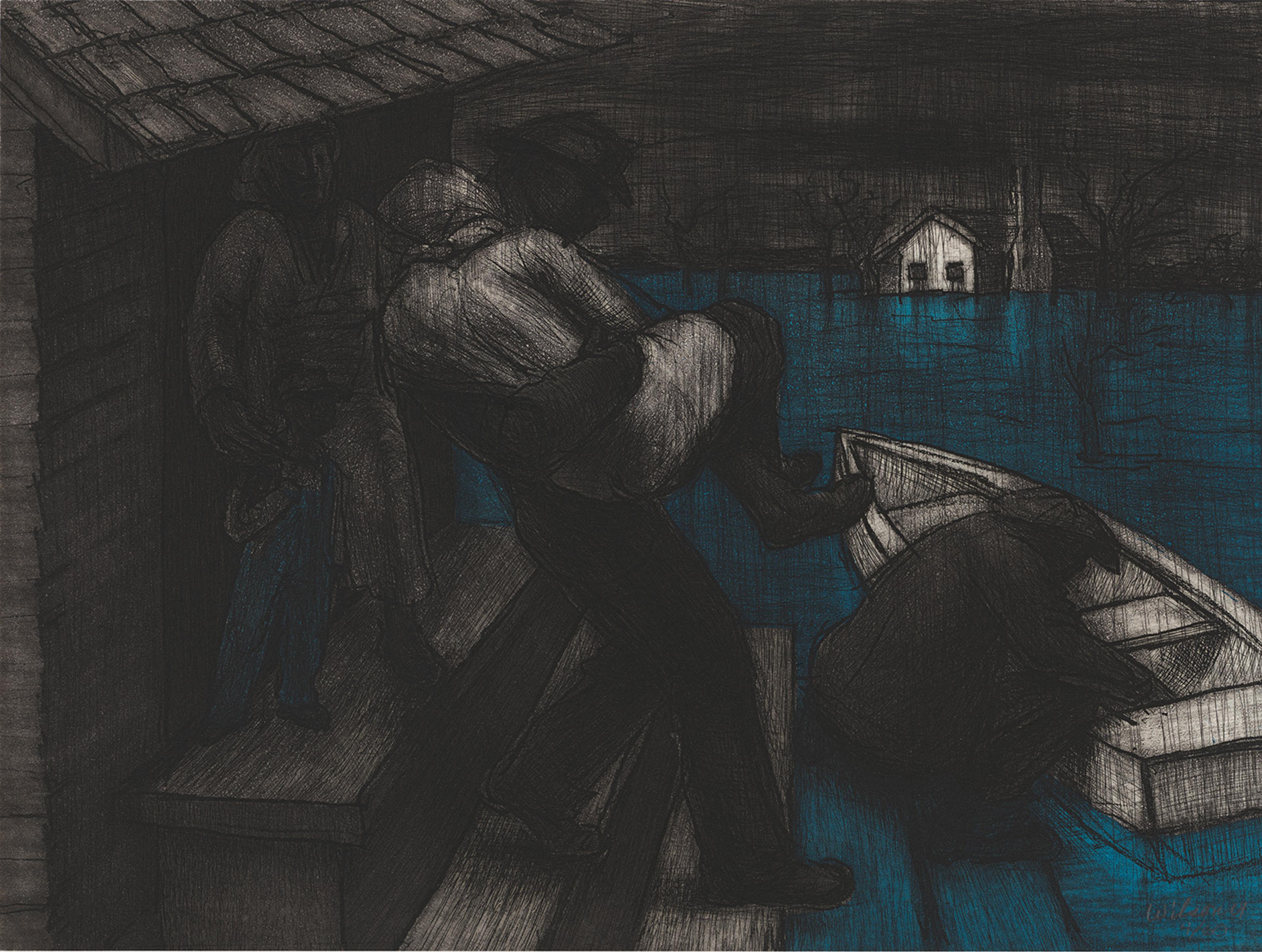

John Wilson (American, 1922–2015). Embarkation, from "The Richard Wright Suite," 2001. Etching with aquatint, 12 × 16 in. (30.5 × 40.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 2023, (2023.264b). Courtesy of the Estate of John Wilson

Payne:

Given your range as a writer—young adult literature, poetry, and more recently children’s literature—what do you think about Wilson’s range as an artist, working with children’s illustrations and perhaps more adult themes in his work?

Reynolds:

I think Wilson is another example of an artist as artist. What I mean is, he proves once more that we can have practices without categories. That we can be categoryless people, besides the category of “people,” at least within ourselves. Did Wilson deal with the secret but perennial conversation about whether there’s a difference between fine art and illustration? Similarly, the “seriousness” of children’s literature is always challenged, as if there is any subject or audience in this world more serious than children. Now we’re seeing all of Wilson’s children’s illustrations, all these years later, which makes me think that perhaps he did feel the echoes of artistic hierarchy bouncing off the walls built to silo him. But he burst through them regardless.

Similarly, the ‘seriousness’ of children’s literature is always challenged, as if there is any subject or audience in this world more serious than children.

Payne:

What aspects of Wilson’s work resonate most with your writing or your life experiences more broadly?

Reynolds:

The use of shadow. There’s darkness that, to me, does a few things. It alludes to the unseen, to the hidden. It also highlights the heaviness that can sometimes exist in Black life. But the best part about shadows is that the darkness is only half the narrative. The other part is that shadows are created by the proximity of light. There is always light. These ideas—characters washed with shadow—make up the backbone of my style.

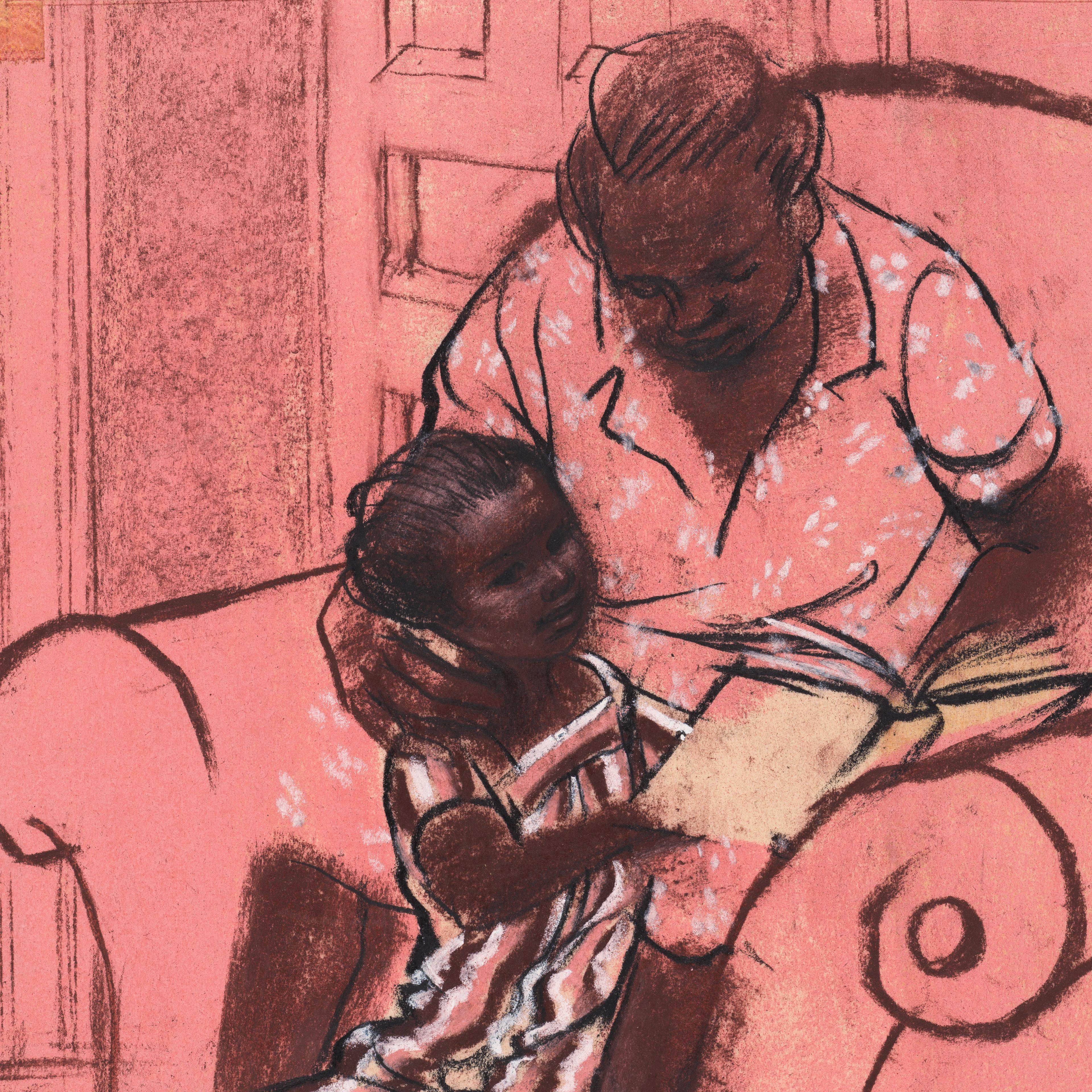

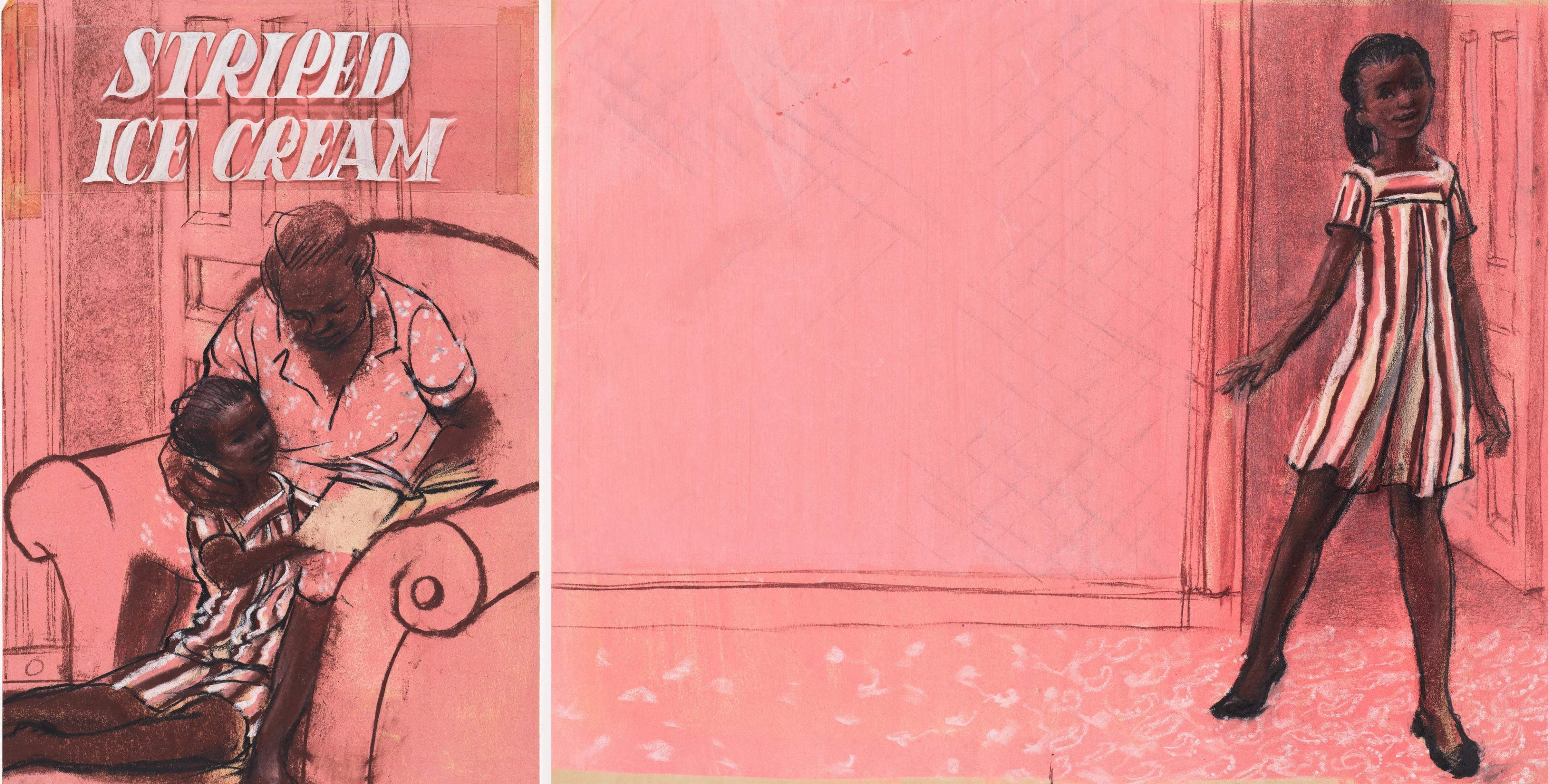

Left: John Wilson (American, 1922–2015). Striped Ice Cream, 1968. Illustrated children's book. Text by Joan M. Lexau (American, 1929–2023). 8¼ × 5½ in. (21 × 14 cm). Collection of Elizabeth and Vivienne Maiden, NY. Right: Study for Striped Ice Cream, 1968. Collection of Julia Wilson, courtesy of Martha Richardson Fine Art, Boston

Payne:

Can you discuss your own experience and trajectory with young adult and children’s literature? How do you think your experience relates to John Wilson’s work on illustrations?

Reynolds:

My story is unconventional, like so many of ours. I started as a poet. Wrote as a child. Then, as a teen, I joined the bourgeoning spoken-word scene of the late nineties, which felt like a resurgence of the jazz poets of the seventies. I also studied poetry in college. I wanted to be Langston Hughes, Amiri Baraka, Gwendolyn Brooks, Lucille Clifton, Mary Oliver, and Walt Whitman. I wanted to be Saul Williams and Jessica Care Moore and Liza Jessie Peterson. I wanted to be Shakespeare of the sonnets. I met another young man named Jason Griffin. He was a visual artist. We lived together in school, and it wasn’t long after meeting that we began collaborating. Poetry and painting mashed into an angsty mush that was honest and interesting at the time. Eventually, we moved to New York, and through a book we self-published in college—which, by the way, has a foreword written by the late, great David Driskell—we ended up landing an agent, who only wanted to meet us because of all the money we'd invested in this independent endeavor.

It cost us thirty thousand to print. Maxed out credit cards, and the ego of youth. This agent would eventually put us in the room with an editor at HarperCollins, Joanna Cotler. The publishers categorized the book as "young adult," which at the time felt like an insult because at twenty-one, I thought I was as grown as I’d ever be. Of course, now I know better, and I also know it was categorized as young adult because my voice was that of a young adult’s. Because… I was a young adult. That’s how it started, but the best part of the story is that our editor, Joanna, told me that I’d move away from poetry as a form, and explore the prose novel. I didn’t believe her, and I told her I had no interest in it, let alone the education for it. And her response was that my intuition would override my lack of education. She was right. But it took a while. When it did, it felt like a fever dream, like I was shooting from the hip but couldn't miss the target.

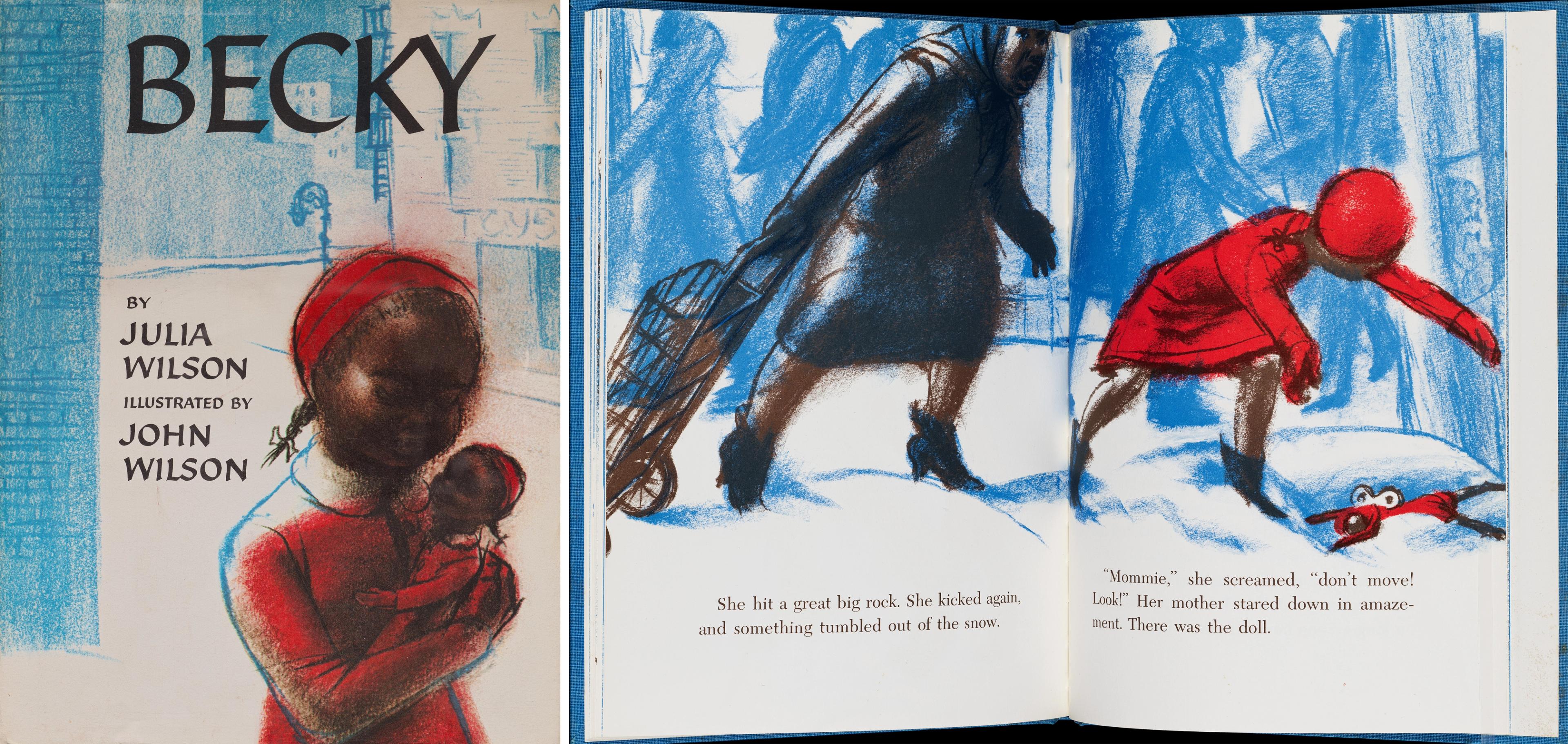

John Wilson (American, 1922–2015). Becky, 1966. Illustrated children's book. Text by Julia Wilson (American, b. 1927) 10⅝ × 6 in. (27 × 15.2 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Ruth M. Campbell Memorial Fund, 2023.620

However, the industry was still resistant to stories about Black children doing nothing but being Black children. Sure, there were (and still are) other brilliant writers working in the space, each of us fighting the same battle—always trying to convince an industry that the stories of everyday Black children not only matter, but are needed. For all children. Especially little me, allergic to the library, not because it wasn’t a sanctuary, but because it felt more like one than a home. And I needed a literary home. A place to kick off my shoes and be myself, where I could see myself.

What I know of John Wilson is that he felt the same way as a young man searching for images of himself, his peers, and family members in museums. A nuanced representation of Black life hanging on the walls, worthy of awe. That’s all I've ever wanted to make as well.

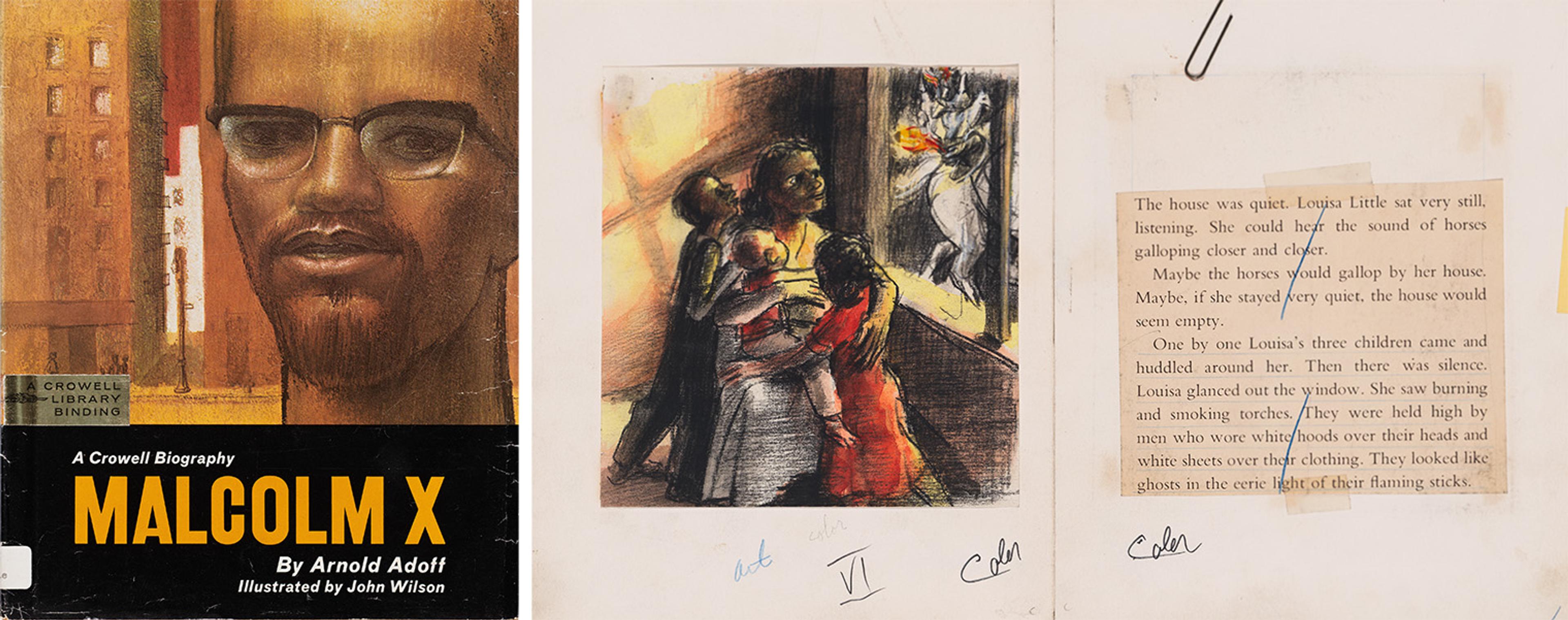

Left: John Wilson (American, 1922–2015). Cover of Malcolm X, 1970. Illustrated children's book. Text by Arnold Adoff (American, 1935-2021). 9¼ × 7¾ in. (23.5 × 19.7 cm). Collection of Elizabeth and Vivienne Maiden, NY. Right: Study for Malcolm X, 1970. Collection of Julia Wilson, courtesy of Martha Richardson Fine Art, Boston

Payne:

In the exhibition, there are a lot of Wilson’s sketches. Repetition and revision are aspects of his practice, and I think of Kiese Laymon and how he talks about revision as a rigorous practice. Can you talk to me about your own process? What do your sketches look like?

Reynolds:

A mess. I’m such an inefficient writer, but that’s only because I believe if it’s not an adventure for me to write it, it won’t be an adventure for you to read it. I figure out what character has been living with me, keeping me up, making me laugh, causing me concern, and what that character wants. And then we go looking for it across hundreds of pages, most of which are unusable. It’s like painting. I start with a wash. Then I add, and add, and add, and sometimes, I have to paint over it all and start again.

Payne:

Could you tell us some of your thoughts on the variety of topics that cross over between your work and Wilson’s? In your book There Was a Party for Langston (2023), there is a clear celebration of Black life and culture, but in All American Boys (2015), there is also the reality of racialized violence that Black individuals face in the United States. How important is it to have this kind of representation for children and teens?

Reynolds:

I want to give a really thoughtful answer here, but the truth is, Black people are alive. And we're living life, not some other thing. It’s life. There are parties. There is pain. There is laughter. There is loss. We are not alien. We are not other. We are awesome and boring and resilient and rest-broken and heartbroken and heavy-handed and sharp-minded and foolish and funny and full of it and full. We are full. And whole. And hallelujah. We are all. That's all.