Over the past year, Peter Hristoff’s Görgü Kuralları (Bahname) (2007) featured in Dialogues: Modern Artists and the Ottoman Past, an installation of modern and contemporary works in the Koç Family galleries devoted to the arts of the Ottoman world of The Met’s Islamic wing. Highlighting the creative approaches to the Ottoman past pursued by three generations of artists from Turkey and elsewhere, the intervention brought the modern and contemporary works into conversation with their Ottoman forebears, raising questions on past and modern social mores, art, history, and traditions. The dialogues between these modern and historical works bridge gaps of time and space to join a greater, global dialogue of modernity.

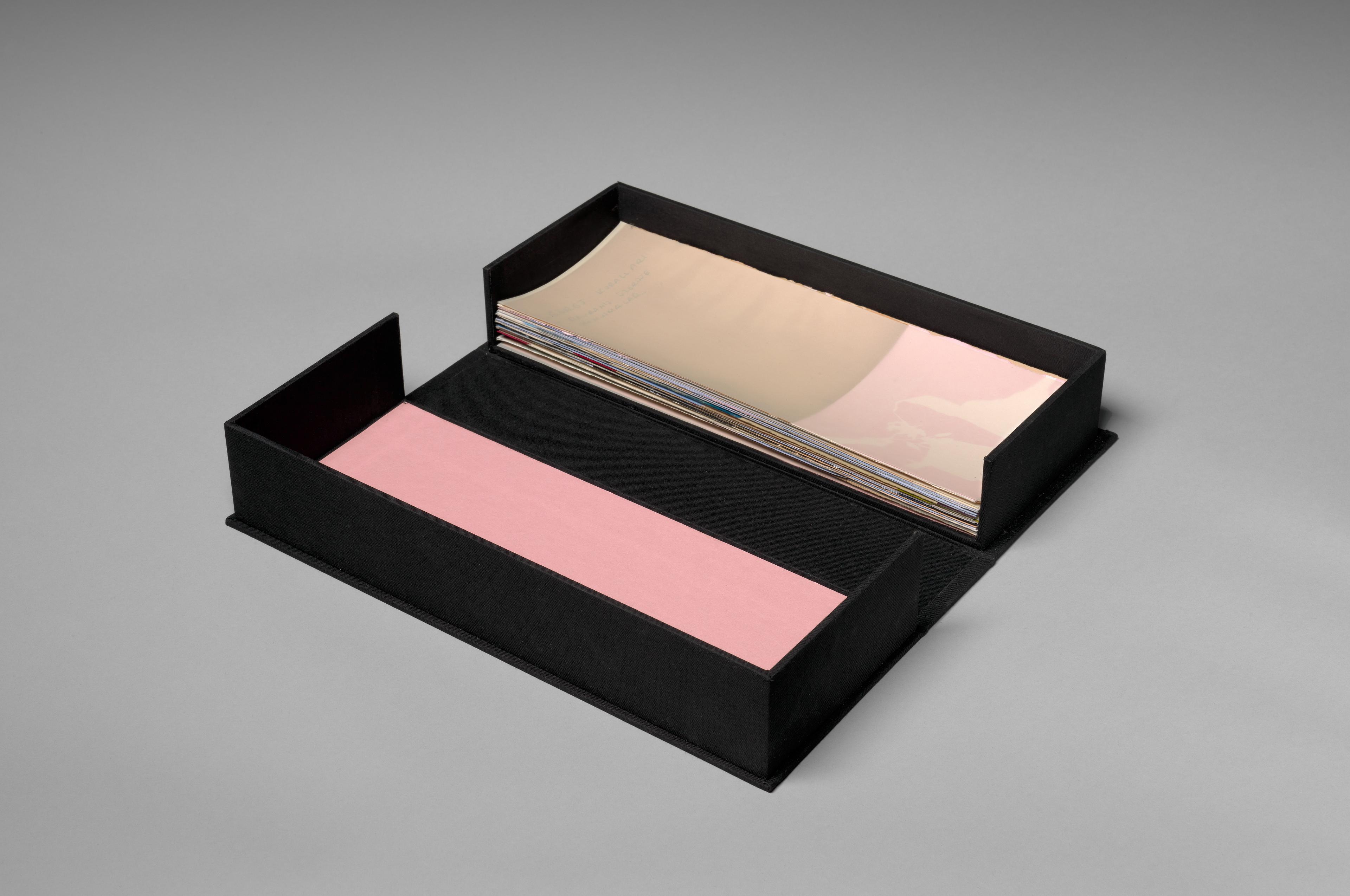

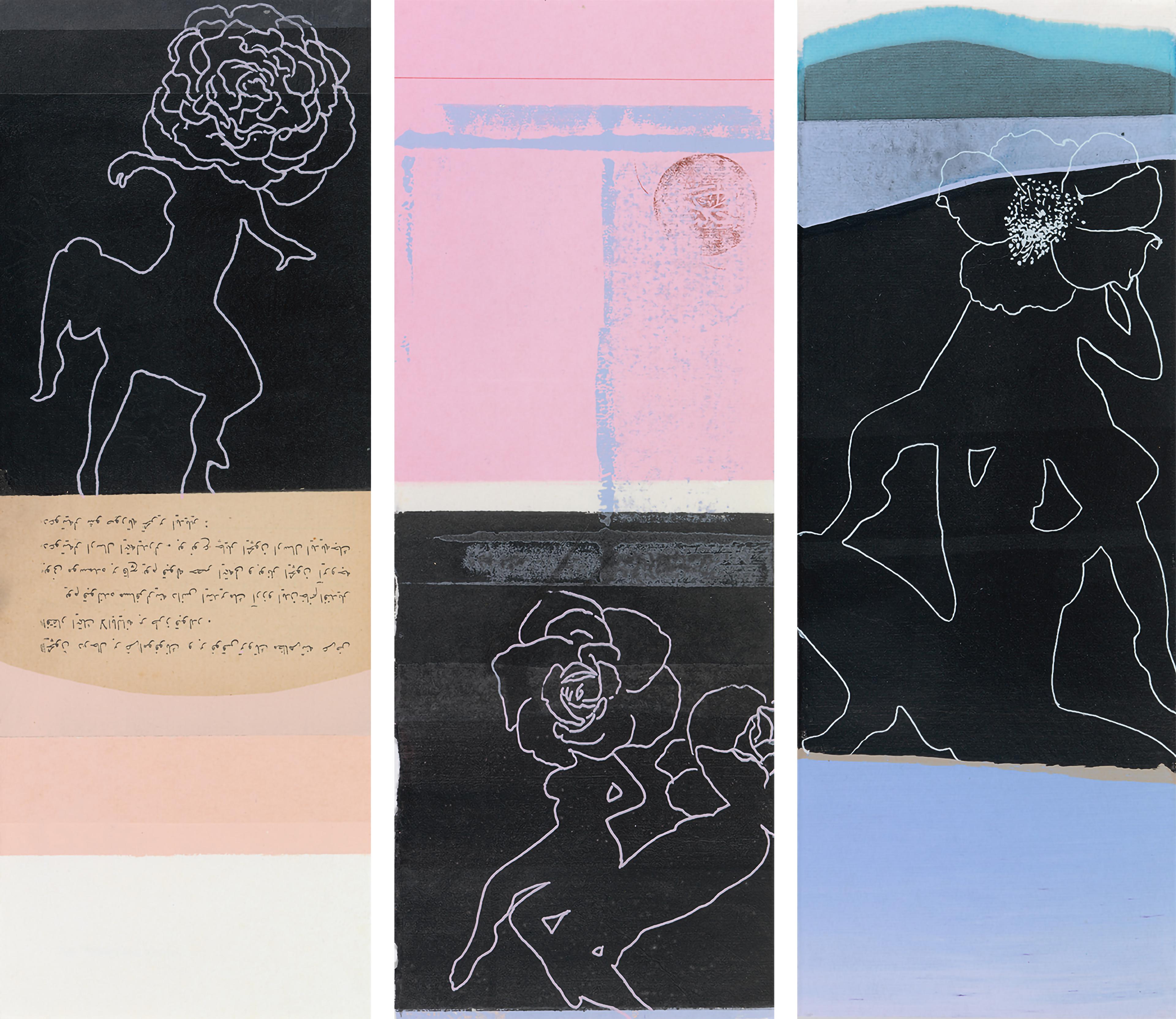

Hristoff’s work, contained within a small black box, consists of twenty-five mixed-media folios, layering Chinese rice paper with pages from a “görgü kuralları,” or Ottoman book of etiquette, and symbols inspired by bahname, Ottoman erotic manuals. The result is a fascinating composition of free-flowing arabesques and floral motifs that transform into genitalia and human body parts, a work the artist describes as sensual both in content and form.

Peter Hristoff (Bulgarian [born Turkey], b. 1958). Görgü Kuralları (Bahname), (2007). Mixed media (ink, watercolor, vinyl, silkscreen) on paper; twenty-five folios in an embossed box, box: 13 1/2 x 5 1/2 x 2 3/4 in. (34.3 x 14 x 7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the artist, in honor of Nur and Selçuk Altun, 2014 (2014.12a–z) © Peter Hristoff

Born to Bulgarian parents in Istanbul and currently working in both Turkey and the United States, Hristoff embraces the duality of his Turkish past and American present. His diverse body of work spans media—paintings, prints, works on paper, textiles—and draws on Ottoman history as well as his own queer identity.

Hristoff spoke with Deniz Beyazit, curator in the Department of Islamic Art at The Met, about his influences and techniques, as well as the role of history, Orientalism, and sexuality in his artistic practice. Their conversation has been edited and condensed for publication.

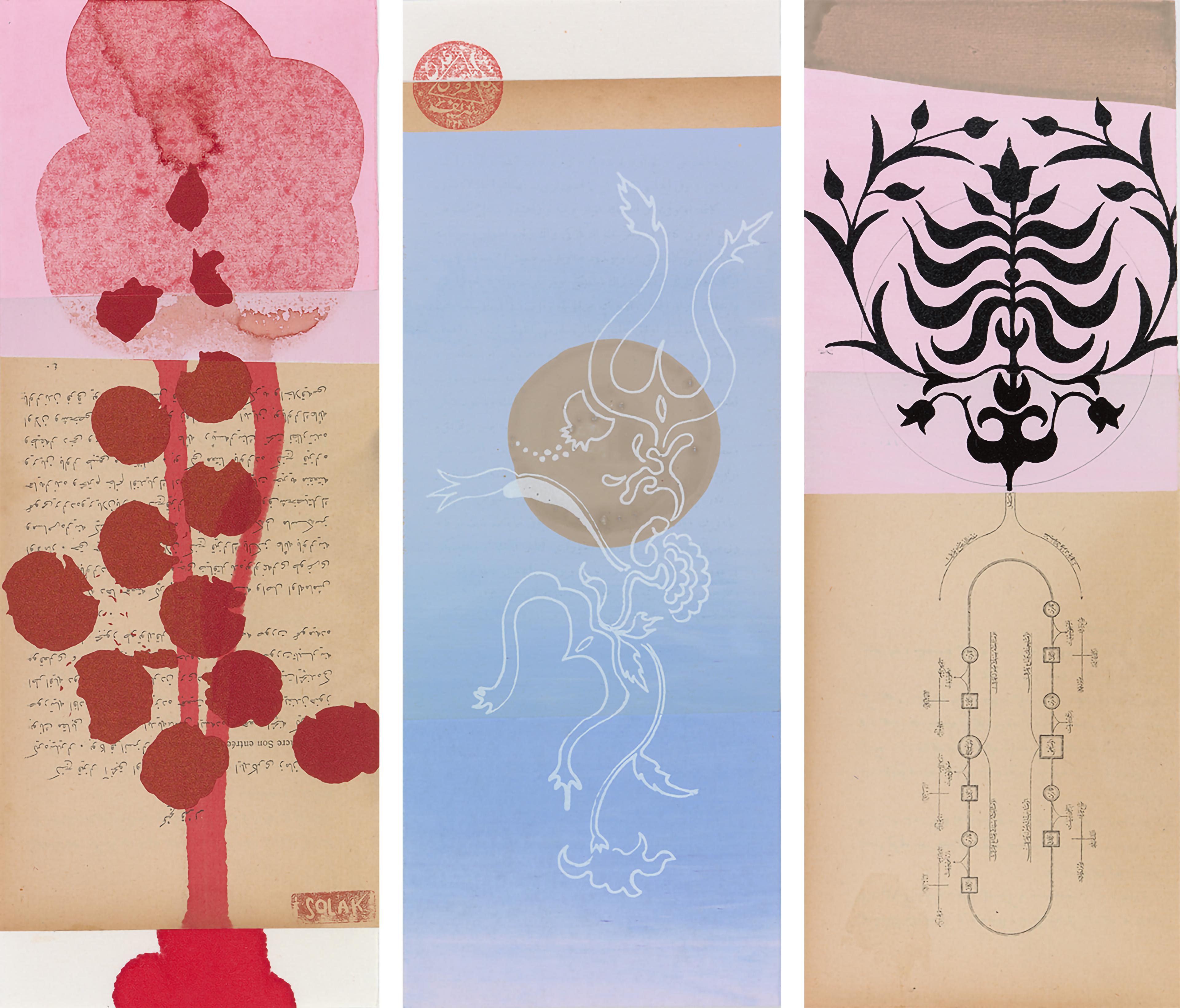

Peter Hristoff (Bulgarian [born Turkey], b. 1958). Görgü Kuralları (Bahname) (detail), (2007). Mixed media (ink, watercolor, vinyl, silkscreen) on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the artist, in honor of Nur and Selçuk Altun, 2014 (2014.12a–z) © Peter Hristoff

Deniz Beyazit:

You’re known to be an artist who is also a scholar because you conduct a lot of research for all your works. You’re also particularly interested in the cultural history of the Ottoman Empire, which is interesting because Turkish artists, especially in the post-Republic decades, often tend to reject their own heritage. There was a prevailing sense that “tradition” was contradictory to the ideals of the Modern Republic. You faced criticism early in your career for your own engagement with that history. Can you tell us more about your family roots and your personal relationship with the Ottoman past?

Peter Hristoff:

My grandparents came to Istanbul right after the Balkan Wars, which displaced many Bulgarian and Macedonian communities. We left Istanbul as a family in the early 1960s; my grandparents moved to France, and my immediate family moved to the United States. I came from a highly cultured family, a family of artists. My father and my grandfather were both artists and collectors.

In terms of my relationship with Turkey—with Ottoman art, Byzantine art, the subsequent art of the Modern Republic—as an immigrant, there’s a kind of both romanticizing and a longing for the motherland, and by motherland I really mean Istanbul and Turkey, because that’s where my parents were born, or where they were raised. Because I was born there and not here, and I moved at an age where I was conscious of that rupture, I was always intrigued by where I came from. Even prior to my adult life, I’ve always felt like I’ve had one foot there and one foot here. I am as much a Turkish artist as I am an American artist. I want both of these qualities, this duality, to exist in my work.

Beyazit:

I’m curious about your relationship to your father’s and grandfather’s art. How did they connect to their own personal and family history? Do you feel like you were inspired by that environment growing up?

Hristoff:

I’ve been drawing and painting since I was a kid. And when we were still living in Turkey, my grandfather would allow me to draw on the walls. A creative atmosphere was encouraged. When I started visiting my grandparents in France as a fourteen-year-old, my grandfather would take me to a different museum every day and give me lessons on Western and French art history. But in the mornings, I would work with him in the studio. He would be on his easel working, and he set up a work table for me in his studio, and we would paint together.

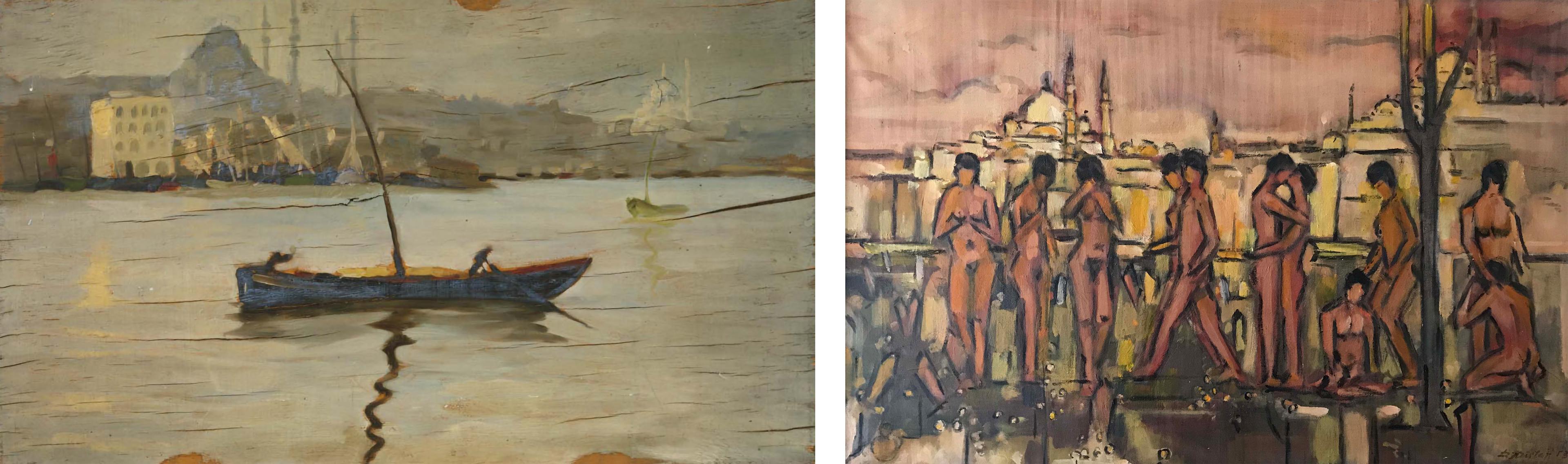

Left: Peter Dimiter Hristoff. Untitled (Istanbul), 1923. Oil on board, 10 7/8 x 18 7/8 in. (27.6 x 47.8 cm). Hristoff Family Archive. Right: Dimiter Hristoff. Unititled, 1953. Oil on canvas, 20 x 30 in. (50.8 x 76.2 cm). Hristoff Family Archive. Both photos courtesy of Jean Vong

My father would always say, “Oh, you’re much more of the type of artist that your grandfather is.” My grandfather was incredibly meticulous, very detail oriented; he loved academic art. And my father was a much looser painter. He was of that generation that was rejecting a certain academic way of working. Not only were they rejecting the traditional crafts and arts of Turkey, but they were embracing the kind of modernism that also rejected strict academic work. I was much more involved in the narrative quality that my grandfather was interested in. When I was studying back in the late 1970s, early ’80s, it was almost taboo to be a narrative artist. But that’s what I was attracted to. I was always attracted to telling stories.

Beyazit:

Let’s look at your work Görgü Kuralları (Bahname) (2007), which we were thrilled to include in our installation Dialogues: Modern Artists and the Ottoman Past. How does this work in particular relate to the Ottoman past, perhaps focusing first on the material aspects—the conscious selections of paper and ink?

Hristoff:

With this piece, I knew that I wanted to create a work that very directly referenced not only a type of book that existed in the Ottoman past, but also to use supplies that referenced work like manuscripts, like books that existed in the Ottoman court. For example, I was very conscious of the type of paper I wanted to use. In my research, I found that throughout early Ottoman history, the paper used came from China.

The second major element is the collage pages from a book of manners that was published in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, in Ottoman Turkish, not in the Republic’s Romanized Turkish; I wanted to use it as one of the layers. In terms of the materials, I wanted to use water-based paints, gouaches, watercolor, some acrylic paint that mimics the quality of gouache, goldleaf, a ruling pen and a reed pen and colors, a palette, that I felt was connected to or mimicked the type of colors that I would often find in Ottoman manuscripts and illustrations.

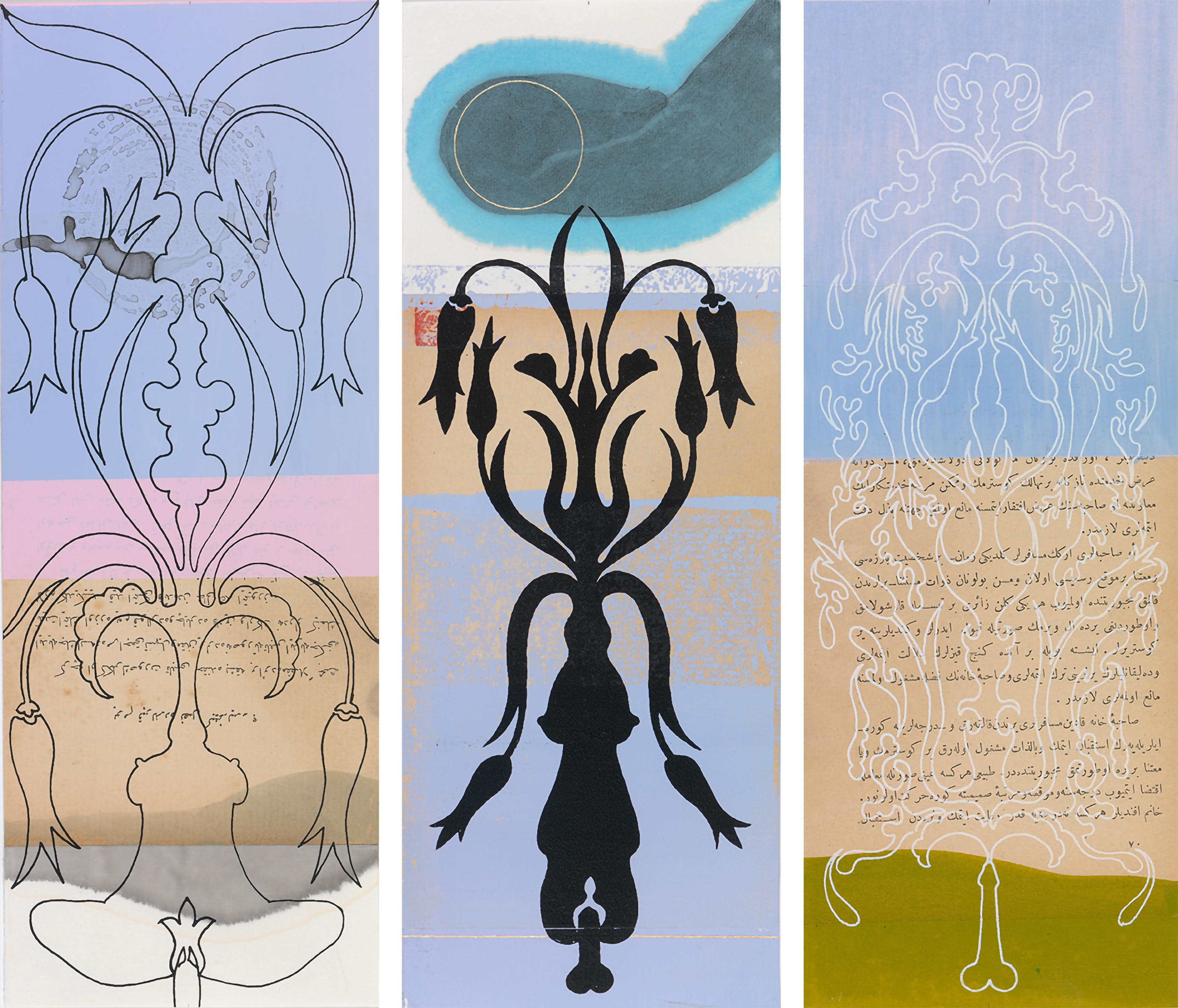

Peter Hristoff (Bulgarian [born Turkey], b. 1958). Görgü Kuralları (Bahname) (detail), (2007). Mixed media (ink, watercolor, vinyl, silkscreen) on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the artist, in honor of Nur and Selçuk Altun, 2014 (2014.12a–z) © Peter Hristoff

Beyazit:

What fascinates me about your work is this idea of layering—it’s almost your signature style. How do you create a physical collage through the selection of papers, but also how do you incorporate screens, creating different visual layers? Can you speak about how this artistic process relates to your creative practice?

Hristoff:

When I was going to school, here in the United States, the idea of narrative was not looked upon favorably. The conversation was, “Is realism dead?” In that environment, where the argument was still about realistic art versus abstract art, students were encouraged to paint simply by making a mark, and then reacting to that mark with another mark. The painting was sort of understood as a culmination of the process of its making, of one reaction after another.

I still start my paintings this way. For me, every painting, every work of art, is a journey. And I almost always start with any kind of loose mark or a field of color, and then decide, okay, what am I putting on top of this, how am I reacting to that, until I get to a point where I feel that this object is complete. Which is not to say that I don’t have a loose idea of what I’m doing with this work. I knew I wanted to create a Bahname. But I certainly didn’t have sketches or a plan of what the images would look like. It’s a matter of allowing the work to unfold, which is exactly what layering does. It unfolds to me and then subsequently the meaning of the work unfolds to a viewer who carefully examines those layers.

Beyazit:

I’m also interested in the layering of meanings and symbols. The title of your work pairs two terms with two different meanings. Görgü Kuralları is an Ottoman book of etiquette and the Bahname is an erotic manual. The work obviously brings to mind modern society, the taboo of talking about sexuality, which at times was also taboo in the past. How does your work address past and present in Turkish society?

Hristoff:

Both of these books are, in a certain sense, books of manners. One is a book of etiquette, and the other one is kind of a book of sexual manners. They both function as instructional manuals. What I found very interesting in the combination of the two, because this also ties into my study of Orientalism, is that the book of manners, the Görgü Kuralları, is pretty directly referencing European manners. So, there’s this book that’s telling you how to behave socially, but also implying a certain hierarchy.

Peter Hristoff (Bulgarian [born Turkey], b. 1958). Görgü Kuralları (Bahname) (detail), (2007). Mixed media (ink, watercolor, vinyl, silkscreen) on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the artist, in honor of Nur and Selçuk Altun, 2014 (2014.12a–z) © Peter Hristoff

The erotic manual is humorous, but it also feeds into a certain kind of fantasy. The word “bah” means sexual desire, and in Farsi, “name” means book. The original Ottoman Bahname that we know of, from the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century, is actually a medical document divided into two parts: the first deals with male sexuality and male sexual health, and the second deals with female sexuality and female sexual health. There are chapters on contraception, on the appropriate time to try to conceive, sort of strict medical information. And in researching this, the commentary has been how accurate they were. They really had a good understanding of this science. With later editions, they became much more about sexual stories. It was more about pleasure, or some type of a funny erotic story that ends with a lesson. The later editions were kind of like very high-end pornography—highly prized, beautifully done, often original works. They would either be given as gifts or, one can imagine, commissioned, and something that obviously only the elite would have access to because only the elite were able to read.

When you’re dealing with any type of an instructional manual, it’s telling you how to behave and how not to behave. And I feel that in life, anything that's telling you what to do or not to do is usually also omitting a lot of what is true to our nature. For me, this goes even deeper in that so much of my work deals with my gay identity. In this particular work, I am referencing heterosexual relations from a gay, non-heteronormative perspective. I wanted to reference the idea of birth, of children, maybe also because that was at a point in my life when I came to terms with the fact that I probably was never going to have a child.

Approximately half the works have what we call the single-source image. In Islamic art, we often see various types of flowers and plants coming out of one vase, or from under one rock. You see this in cut paper art of the Ottoman period, in tapestries and rugs, and probably most of all in Iznik tiles. The implication is that all life, no matter how different in appearance, comes from one place—God.

Left: Textile Fragment, mid-16th century. Turkey, probably Istanbul. Silk, metal wrapped thread; lampas (kemha), 24 x 26 1/2 in. (61 x 67.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1952 (52.20.22). Right: Dish Depicting Two Birds among Flowering Plants, ca. 1575–90. Turkey, Iznik. Stonepaste; polychrome painted under transparent glaze, 2 3/8 x 11 1/4 in. (6 x 28.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of James J. Rorimer in appreciation of Maurice S. Dimand's curatorship, 1933–1959, 1959 (59.69.1)

I wanted to use that idea, but in this work, I wanted to refer to the female body, to the uterus, as the source of life. So in many of the pages, where we see these stylized flowers and leaves, they’re directly commenting on this idea of the single source, but they’re emerging from what appear to be the uterus or the vagina of the female figure. In some, there’s also a stylized penis that rests just under the vagina. It all becomes very arabesque and curlicue. Surprisingly, many viewers don’t see the genitals; they just see the floral motif.

Beyazit:

The way you bring to surface certain stereotypes is fascinating, and I’d love to talk more about how this piece is also a response to Orientalism. Since the exoticized female body is often at the center of Orientalist painting, seen from the Western gaze through a lens of fantasy.

Hristoff:

I think the male body is also eroticized in Orientalist work, but it just hasn’t been talked about as much. It’s a really complex issue. It’s difficult because there are Orientalist works that I really love, that I could very easily be seduced by—not only the skill of many of those artists, but it also goes back to what I said about my grandfather, that very skilled type of realistic painting—I really admire that. I love Jean-Léon Gérome, but at the same time, as someone who has lived in Turkey and spent so much time there, I also see how ridiculous and cliché so much of it is. It’s based on Western fantasies. Simultaneously, the East has fantasies about the West. You have books of Western etiquette that are embraced, or, in Turkish we use the French expression, “comme il faut,” as it should be, in terms of behavior. The fact that the term for how to behave is a French word in Turkish, I find particularly funny.

I made this work in 2007. It was the first time I addressed this idea of the Bahname. I started to do some research about erotic art and literature in the Ottoman period. Initially, everything seemed to originate from the male perspective. I’m not a woman, I’m a gay man, but in this particular work, I wanted it to be about a female perspective. In my research, though, I realized that the female perspective is actually very strong. So much storytelling in Turkey comes from the women of the village who tell many of the stories. So I, too, harbored certain Orientalist fantasies. I thought, “Oh, I really want to address female sexuality”—and then learned that it’s been addressed for quite a while. The stories are maybe a little harder to find than those told from a male perspective, but they exist.

Beyazit:

How were you able to access female perspectives on sexuality within the Turkish tradition?

Hristoff:

The frustration with so much in my research, in my life, in my experience of Turkey, is that the culture is still very male, even though the matriarchy is so powerful. My mother and her sisters never talked about this kind of stuff openly, they never talked about sex. So I’ve always imagined that the conversation between women must be so fascinating. There’s a wonderful book called Regards from the Dead Princess (1987) by the French writer Kenizé Mourad. She writes in the perspective of I think her great-grandmother, who’s part of the Ottoman aristocracy. She was going to be married off to an Indian prince. She went through this whole process prior to her wedding of sexual education by the female members of her family. Then her husband refused to believe that she was a virgin because she was so good in bed and he sent her back to her family.

For a long time, I was really interested in the embroidered flowers that are on the edges of Anatolian headscarves. The Anatolian headscarf is very different from a veil. It’s used as a way for the women to protect their hair when they’re out in the sun, when they’re working in the field. It’s a way to show their modesty. But surprisingly, because the headscarf also has all of these embroidered flowers, it’s a way of framing their beautiful faces. The flowers, depending on the village, all have a symbol. So if you have a son, and you’re looking for a bride for your son, you will wear a headscarf with a certain type of flower. And the other women in the village will know: “Oh, so and so has a son, he’s of marrying age, and they’re looking for a girl.” The language between women in Anatolian culture is incredibly fascinating. For many years I would collect these headscarves, which are called oyas, and they would be the first layer in my paintings. I have many paintings where oyas come out of mouths. That’s the language that’s used.

Left: Peter Hristoff (Bulgarian [born Turkey], b. 1958). Untitled (detail), 2022. Embroidered cotton and silk headscarves, 12 ft. 8 in. x 15 ft. 10 in. (386.1 x 482.6 cm). Collection of the artist, Photographed at Yapi Kredi Cultural Center, Istanbul © Peter Hristoff. Right: Peter Hristoff (Bulgarian [born Turkey], b. 1958). Breath, 2000. Mixed media on canvas over panel, 45 1/4 x 18 1/2 in. (115 x 47 cm). Private collection, Istanbul © Peter Hristoff. Photo courtesy of Jean Vong

Beyazit:

Your work often connects with homosexuality. Can you tell us a little bit about your artistic past and trajectory? Even if in this case the source is about the female body, is there still a connection to your sexual orientation?

Hristoff:

I emerged as an artist out of school right at the beginning of the AIDS crisis. My teachers, my friends, my first art dealer, were all affected by this. Many of them died in the period between the early 1980s and the early ’90s, before there was really ground made in developing treatment. In 1986, when I went to Turkey for my first extended stay there to work, I made a suite of paintings that were all inspired by Ottoman türbes. A türbe is a kind of symbolic mausoleum. The bodies are actually buried in the ground, beneath the mausoleum, and the displayed and draped caskets, often luxurious and highly decorated, are empty. I somehow felt that the experience of visiting the türbes, seeing them, seeing people conversing and relating and praying to these mausoleums, when the bodies actually were not there, I felt like that was what was happening in my life. That I was conversing, I was involved with people that were no longer there. They were taken away in such a quick and strange way that I had never experienced before. I can’t begin to describe to you what those years were like. It was really, really horrible. People were dying so quickly.

Peter Hristoff (Bulgarian [born Turkey], b. 1958). Türbe Paintings, 1987–1990. Oil on panel, each 12 x 12 in. (30.5 x 30.5 cm). Private collection, New York © Peter Hristoff. Photo courtesy of Jean Vong

Up until then, I was an abstract painter. At that point, I thought, I can’t be an artist and not talk about this, and that’s approximately when I also started to use the silhouette. Because the silhouette was not only my body, my male body in the world, but it was every male body. And as a gay man, I was particularly interested in referencing the gay male body in the world, both with its strength and its vulnerability. Somehow I was able to find symbols and ideas in Ottoman art that I could use, probably because so much of the Islamic art that I admire is about the idea of the afterlife. On the other hand, as a young man, all of that still does not deny your sexuality and ideas of sensuality.

Beyazit:

I’m interested in the shifting perception, historically and contemporarily, of conservative Victorian ideas of sexuality rooted in reproduction and conception which were often contrasted with an Orientalist view of the East as a more sexually promiscuous space. And today, when modern ideas of sexuality have become more focused on pleasure, there’s sort of a reverse Orientalism of these cultures as sexually conservative. How are these social contrasts at play in this work?

Hristoff:

It’s incredibly complicated. The whole sort of connection of Orientalism and homosexual desire is really strong. There’s tons written about it, but you have to dig for it. It’s this idea that the male is somewhat more open to experimentation until they get married, you know, because of the value placed on female virginity. And that’s also a bit of a joke in a lot of these stories in the Bahname. Like, we can’t do anything with our girlfriends, so you know, we can have fun together. This goes back for centuries. Also, a lot of the stories are gay. They’re about bathhouse culture.

With this work, I was interested in talking about sensuality in general. If the figures and the images are viewed carefully, there are references to the idea of touch, of body, of penetration, but penetration not only of the flesh, but of ideas. I wanted to create as sensual a work as possible with this book, that could be received as being sensual by the viewer, independent of their sexual orientation. That applied to the materials as well. The French have a word called la touche, the touch—it’s used for paper, for paint, for strokes. I wanted la touche in these works to be very sensual. I used paint, either gouache, or a paint called flashe, which is incredibly powdery. It really has a touch, it asks to be touched, but it also picks up fingerprints really easily. The images of fingers in the work, of hands, the arabesque—which, being curvilinear, is a sensual form by its very nature. Beyond everything, I just wanted to make something that was really sexy. Obviously with lots of ideas behind it, but I just wanted to make something that was sexy.

Peter Hristoff (Bulgarian [born Turkey], b. 1958). Görgü Kuralları (Bahname) (detail), (2007). Mixed media (ink, watercolor, vinyl, silkscreen) on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the artist, in honor of Nur and Selçuk Altun, 2014 (2014.12a–z) © Peter Hristoff

In addition to the single-source motif and the commentary on the female body as the source of life, there are also images that are hidden, very faint, done with a very fine line. There are all of these figures, but they don’t have human heads—the head is a completely open rose. The open rose, as far as I have studied, is a symbol of submission to a greater force. So if you have a body, a beautiful naked body, with its head being an open rose, what is the implication? That you are allowing yourself to experience physical pleasure. You know, it just hit me like a ton of bricks right now. I think after years of dealing with the danger of the repercussions of physical pleasure, it’s asking, what does it mean to be able to celebrate it, without fear, without hesitation?