Power Figure (Nkisi N'Kondi: Mangaaka), 19th century, inventoried 1912. Kongo peoples; Yombe group. Democratic Republic of the Congo, Chiloango River region; Republic of the Congo; Angola, Cabinda. Wood (Vitex thonneri De Wild.), iron, resin, cowrie shell, animal hide and hair, ceramic, plant fiber, textile, pigment; H. 52 in. (132 cm), W. 19 1/4 in. (49 cm), D. 13 3/4 in. (35 cm). Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium

During the early stages of preparing for the exhibition Kongo: Power and Majesty, a team of conservators and scientists began a technical investigation of the large power figures known as Mangaaka, which were created in the Chiloango River Region on the Loango Coast during the second half of the nineteenth century. The initial focus of the investigation was the materials and methods of construction of our own Mangaaka, but shortly thereafter—through collaboration with a number of American and European museums and individuals whose collections house these figures—the study expanded to include a majority of the other fourteen Mangaaka power figures now on view in the exhibition.

Bearing the attributes of a Kongo chief, these works are known as power figures because they served as containers for bilongo, or spiritually charged medicinal matter. Bilongo was prepared by the ritual priest, or nganga, who placed it at several key sites: behind the eyes, in the stomach, attached around the jawline as a resin compound on an iron armature, and wrapped around the waist in raffia bundles. In this way, both the figure itself and the external attributes acted as containers for bilongo; the whole complex, when combined with ritual action, evoked the ultimate spiritual force of law and order: Mangaaka.

So what materials make up a Mangaaka power figure?

Wood

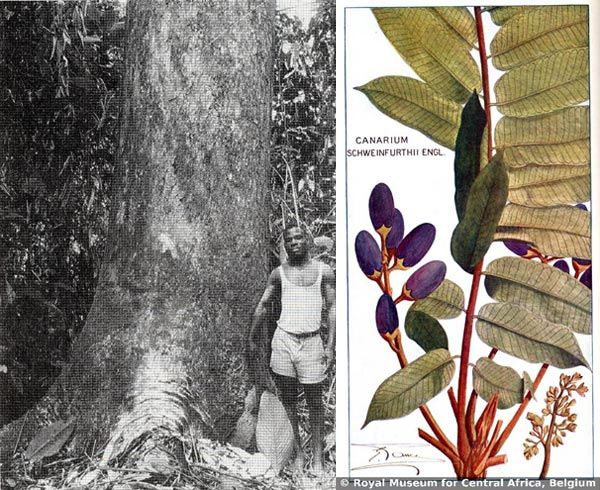

Previous technical studies have indicated that the wood used for carving Mangaaka and other types of nailed power figures is commonly the large tropical tree known as Canarium schweinfurthii Engl. Several Mangaaka figures in the exhibition were found to be carved from this dense sacred wood, including those from the Detroit Institute of Arts and the Dallas Museum of Art.

Left: Photograph of Canarium schweinfurthii Engl. (Source: Y. Tailfer, La foret dense d'Afrique centrale: identification pratique des principaux arbres (1989), p. 952. Right: Canarium schweinfurthii Engl. fruit and leaves. (Source: C. Vermoesen, Manuel des essences forestières de la région équatoriale et du Mayombe. Bruxelles: Imprimerie Industrielle & Financière: 1931).

Another anatomically similar wood, also from the Burseraceae family but of the Dacroydes genus, has been suggested as an alternative for the Metropolitan and Pigorini figures. Both trees have straight boles suitable for carving large-scale sculptures, and both have traditionally been exploited for their timber and aromatic resins. Some species have also been exploited for their edible fruits.

Resin

Medicines were packed into and concealed within Mangaaka figures in resin-lined internal cavities. The major cavities were located at the eyes and stomach. Bilongo was also concealed within the resinous mass of the beard.

Chemical analysis of several samples taken from the beard, eye-inlay sealant, and stomach power pack of different Mangaaka figures shows remarkable consistency in formulation. A highly specific combination of ingredients, consisting of an oleo-resin (such as a tree exudate or sap-like material) mixed with kaolin, quartz, vegetable matter, and oil, was used. The oleo-resin derived from scoring the bark of C. schweinfurthii itself was initially considered a likely ingredient on the basis of some chemical components. Comparison with a wider range of resins, including aged and heated samples from this tree species, suggests that a combination of plant sources was likely used.

On a research trip to the Yombe region of the Republic of the Congo, we were able to take a sample of the wood and the oleo-resin from a small C. schweinfurthii tree. It was known locally as nsafu and was well known as a tree exploited for its timber. The sap resin of C. schweinfurthii was traditionally used for bush candles and varnish coatings; other parts of the tree itself have known medicinal and practical purposes.

Left: Conservator Ellen Howe holds a sample of bark up against a small C. schweinfurthii tree near Lake Cavo, Republic of the Congo. Right: Ellen Howe and her research team with a branch from the C. schweinfurthii tree, collected near Lake Cayo. Photographs by James Green

Animal Hair and Hide

Emerging from the sides of a Mangaaka figure's beard would have originally been long strips of animal hide and hair. Analysis of the hair on the figure from the Royal Museum of Central Africa, Tervuren, has identified it as Chimpanzee, according to Marieke van Es, a conservator at that museum. The hair on both the example from the Wereldmuseum in Rotterdam and that from the Pigorini is possibly from the Angolan colobus monkey (Colobus angolensis), which was common in this region in the nineteenth century.

Left: Angolan colobus monkey (Colobus angolensis). Photograph © Tony Northrup 2015. Right: Power Figure (Nkisi N’Kondi: Mangaaka), 19th century, inventoried 1906. Kongo peoples; Yombe group. Democratic Republic of the Congo, Chiloango River region; Republic of the Congo; Cabinda, Angola. Wood, iron, resin, cowrie shell, animal hide and hair (tail of Angolan colobus monkey?), ceramic, plant fiber, pigment; H. 41 3/4 in. (106 cm), W. 17 3/4 in. (45 cm), D. 17 3/8 in. (44 cm). Wereldmuseum, Rotterdam (10633)

Shell

A large cowrie shell, Cypraea stercoraria, with its aperture facing the viewer, was impressed into the still-plastic resin at the front of the stomach protuberance in the majority of Mangaaka power figures. A form of currency, these would have been imported into the region from the Indian Ocean.

Detail of the Dallas Museum Mangaaka's stomach protuberance with inserted cowrie shell (Cypraea stercoraria). Photograph by Ellen Howe

In the Grand Marché in Pointe Noire, in the Republic of the Congo, it is still possible to buy cowrie shells, which continue to be used by traditional healers.

A market seller in the Grand Marché in Pointe Noire lifts a basket containing small cowrie shells. Note in the foreground balls of white kaolin clay, which was also used as surface decoration on these nineteenth-century figures. Photograph by James Green

Ceramic Tile

Brilliant white semicircular or oval-shaped inlays, found to be cut from flat ceramic tiles, are positioned over the eye cavities and held in place by the same resin discussed above, which can be seen covering the inlay edges. Chemical analysis of a micro-sample of the tile indicates the white color is produced by lead-tin glaze typical of nineteenth-century European manufacture.

Power Figure (Nkisi N'Kondi: Mangaaka) (detail of eyes), 19th century, inventoried 1909. Kongo peoples; Yombe group. Cabinda, Angola, Chiloango River region. Wood, iron, resin, cowrie shell, ceramic, plant fiber, textile, pigment; H. 43 1/4 in. (110 cm), W. 17 3/8 in. (44 cm), D. 16 1/2 in. (42 cm). GRASSI Museum für Völkerkunde zu Leipzig, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Photograph by Ellen Howe

Black Pigments

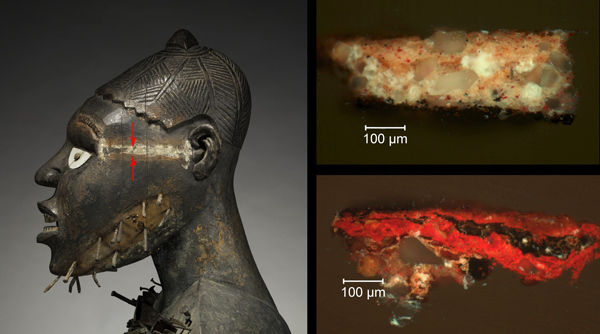

The black overall coating applied to the figures is a vegetable substance in a proteinaceous binder, probably a tannic dye similar to those used to blacken African materials such as textiles, basketry, and ceramics. The head of a Mangaaka figure often has more than one layer, suggesting this pigment was reapplied during ritual use.

Left: Right side view of the head of the Metropolitan's Mangaaka. The red arrow shows where a black flake was sampled. Top right: Image of the cross section showing the wood and the black coating. Image taken under conditions of reflected visible light. Bottom right: The same cross section under ultraviolet illumination, showing a greyish fluorescent proteinaceous layer on the wood followed by the black coating. Image courtesy of Adriana Rizzo

White and Red Pigments

White and red clays were applied to the cheeks, temples, and eyes and to the figures' attributes—the hat, anklets, and armlets, as well as the block below the feet.

Left: White and red pigment on the face of the Dallas Museum's Mangaaka. Right: Pigment added to the block of the Manchester Museum's Mangaaka. Photograph by Ellen Howe

White kaolin clay, a sacred substance collected from streambeds, was associated with the land of the ancestors. It contains relatively large quartz fragments, possibly added for grinding purposes. Similarly large quartz crystals and kaolin in the resin sealant attest to this clay's important role in spiritual matter—and the figure's command over both the material and spiritual world.

Left: Left side view of the head of the Metropolitan's Mangaaka. The red arrows show where white and red flakes were sampled. Top right: Image of the cross section of the white kaolin clay, including some red iron oxides, and large transparent quartz particles. Residues from the underlying black paint are visible at the bottom. Bottom right: Image of the cross section of the red clay paint on top of the white kaolin clay, described above. Taken under conditions of reflected visible light. Image courtesy of Adriana Rizzo

The red pigment consists of an iron oxide-rich clay, probably the so-called lateritic residual soil that is widespread in the region and results from extensive weathering.

A redwood pigment called tukula was sparingly applied on the stomach mound, beard, and chest. This fibrous pigment was obtained by rubbing heartwood blocks of redwood together, and was further ground on a wooden slab with quartz. Often it was compacted into a shape with palm oil to be used in rituals but also as a medicine and type of body paint. Chemical analysis has indicated that in most of the objects tested the tukula derives from the locally available Pterocarpus soyauxii Taub. (commercially known as African Padauk).

Due to fading from light exposure, the tukula has often lost its vibrant red color and now appears as tan-brown, sometimes mistaken for dried mud. Its original color is evoked in a sample of redwood powder kept in a lidded raffia box in the Royal Museum for Central Africa.

Sample of tukula from Kongo basket (inv. EO.0.035194). Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren. Photograph by Ellen Howe. With special thanks to Julien Volper, Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren

Bilongo

Bilongo is made up of a variety of animal, vegetable, and mineral materials, such as those still found today in the Grand Marché in Pointe Noire. In the image below you can see a number of different materials including nineteenth-century glass beads, parrot skulls, nuts, dried seeds, fruit, stone, old currency, bones, and pieces of mica described as "fragments of rainbow." Seeds of Canarium schweinfurthii and Arecaceae (a kind of palm) are also available for sale.

Produce available from a healer's stall in the Grand Marché in Pointe Noire, in the Republic of the Congo. Photograph by James Green

Seeds of the climbing legume Dioclea sp., also known as the sea bean, are used for a variety of illnesses including the treatment of neurological diseases.The nganga was responsible for selecting and combining these materials; knowledge of the exact mixtures was restricted to him alone.

If we had access to the bilongo in each of the power receptacles, we would be able to learn more about the materials used to invoke Mangaaka's force. However, because the bilongo is either still hidden within its receptacles or because it was emptied out by the nganga before the works left the region, we can only speculate as to the type and nature of the contents by comparing medicinal matter found in other types of minkisi. We'll address this topic in an upcoming post about another power figure in the Metropolitan's collection.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge James Green, research associate in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, and Chika Mori, 2014–15 Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in the Department of Scientific Research, for their invaluable contributions to the blog post and research project.