Around 1748, the young British furniture maker Thomas Chippendale (1718–1779) moved from his home in Yorkshire to London, a cosmopolitan city full of opportunity but also stiff competition in the luxury trades. Although there was no guarantee that his business would succeed, within a decade "Chippendale" had become a household name and a hallmark of quality British furniture.

One of the crucial factors in Chippendale's astonishingly quick rise was the book he published in 1754, The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director. Filled with 160 pages of furniture designs, the Director presents Chippendale as a versatile, skilled designer in tune with the lifestyles of modern society, from the country nobleman and urban gentleman to the newly affluent merchants of the middle classes.

Chippendale's designs soon spread throughout the British Empire, following the routes of the nation's expanding maritime trade and colonization of North America and the Caribbean. As talented craftsmen and consumers adopted his designs and aesthetic, blending them with their own local traditions, the name Chippendale came to refer not just to a prominent London cabinetmaker but also to an enduring style, one that has played a central role in British and American furniture design for more than 250 years.

To celebrate Chippendale's three hundredth birthday, this exhibition explores how he came to create the Director during his early years in London, and how the book's widespread influence afforded him the iconic status he enjoys to the present day.

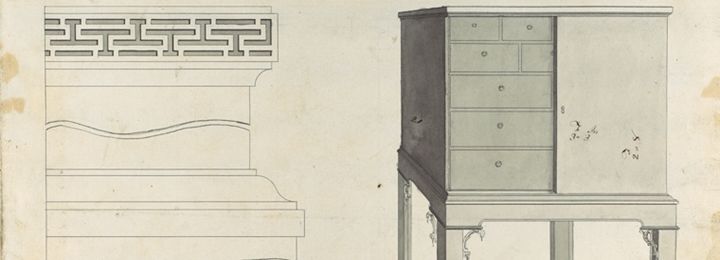

Chippendale published his Director in 1754, about six years after he arrived in London. The handsome volume included designs for almost every type of moveable furniture a modern household might need and in a range of styles and levels of luxury, from a simple undecorated clothes press to a library cabinet with rocaille ornaments or Chinese fretwork. In terms of its size and scope, the Director was unparalleled in the English-speaking world. It is chiefly through the eager reception of this remarkable book that "Chippendale" quickly became a household name. How Chippendale first conceived of the idea for the Director is not known, but the concept of the book resonated with developments in the British art world of the period, especially the emergence of drawing education. In the 1747 London Tradesman, for example, young cabinetmakers were advised to learn how to draw, since the key to a successful business lay in the ability to design new things. It is tempting to think that Chippendale read this advice before moving to London to establish himself as a furniture maker, for he would soon become the living example of its efficacy.

After decades of religious and political instability in Great Britain, the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 signaled the nation's rise to a position of economic strength rivaling that of its neighbors on the European Continent. With this success came a new sense of cultural self-awareness and desire for artistic independence. As British architect John Gwynn (1713–1786) wrote in his influential Essay on Design (1749), "England's art should reflect her triumphs on the sea, in trade, and elsewhere. . . . [so that] men of taste [will] visit England as Englishmen now visit Italy." The search for a British artistic and cultural identity was expressed foremost in the celebration of national heroes through luxurious publications, many of which included anthologies of their works. Colen Campbell's Vitruvius Britannicus (1715–25), for example, made a bold statement about the exemplary quality of British architecture. By publishing his own designs alongside those of masters such as Inigo Jones and Sir Christopher Wren, Campbell provided his work with an immaculate pedigree, but he also created for Britain a genealogy of domestic architecture comparable to that of Italy and France.

In the late seventeenth century, tradesmen of all kinds began to adopt the medium of print for promotional purposes. In addition to advertisements in newspapers and magazines, trade cards were an important tool through which they could reach a large body of customers. The format was likely invented by seventeenth-century booksellers, who pasted small labels into the books they sold in order to advertise their business. These labels and trade cards consisted of a short text detailing the name and specialty of the tradesman and an image of either the shop's sign or other attributes related to the wares and services offered. In the eighteenth century, trade cards became more elaborate, and numerous London engravers came to specialize in the genre. In many cases billing information was written on the back, allowing us to date these highly imaginative prints and providing insights into the consumer patterns of the period.

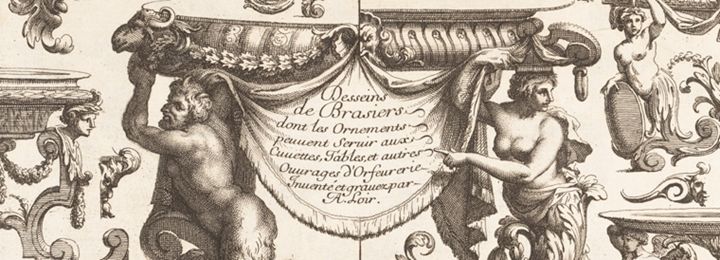

In the second half of the sixteenth century, designs for furniture and other decorative art objects began to be reproduced and sold in print form on the European Continent. These early furniture prints were often made by the cabinetmakers themselves in order to advertise their artistic virtuosity. Initially they differed greatly in style, quality, and number, but during the seventeenth century, following the standardization of the print market, a new format arose known as the livre or cahier: typically a set of six prints focused on a specific subject. A number of professional designers emerged whose principal occupation was the output of these prints. French artists such as Jean Lepautre (1618–1682), Jean Bérain (1640–1711), and Daniel Marot (1661–1752) published numerous designs for furniture and the interior, influencing other artists across Europe. During the eighteenth century, their works were collated and reissued in luxurious publications, a comprehensive archive of design that fed the interests of both craftsmen and an emerging group of print collectors. Chippendale modeled his Director after this type of publication.

The establishment of a mature printing trade in England during the first decades of the eighteenth century was an essential part of British efforts to create a national artistic identity. Following Continental precedents, British artists either learned how to etch and engrave or hired professional printmakers to create print series after their designs. Particularly after the adoption of the Engraver's Copyright Act of 1735, which prevented unauthorized copies of original designs, the number of British publications grew exponentially. Of great importance to the furniture trade were the print series by the successful designer and carver Matthias Lock and his colleague Henry Copland featuring their signature Rococo designs. Following the model of the Continental cahier, Lock's first print series, Six Sconces (1744) and Six Tables (1746), were modest but skillful attempts at a British response to France's still-dominant Louis XV style. Although such prints had already established a model for publishing furniture designs by the time Chippendale moved to London, these relatively simple publications did little to anticipate the scope and ambition of the Director.

In the decades following the Great Fire of 1666, which devastated the medieval center of London, the city was rebuilt, rising to become not only the most modern city in Europe but also a thriving hub of commercial activity. Trade and labor were key to that success, and by the eighteenth century London could boast no fewer than 360 trade groups. Artists, artisans, and laborers of all kinds were attracted to the capital to cater to its growing population and to the new wealth of the merchant and middle classes. Covent Garden, the neighborhood of Chippendale's first-known London address, lay at the heart of London's modernization and established a model for the revitalized city. He moved twice within the same district, living first at Northumberland Court near the Strand, where he worked on the Director, before settling at 60-62 St. Martin's Lane in 1754. The street was a nexus of artistic activity and home to a concentrated population of cabinetmakers and carvers as well as St. Martin's Lane Academy, the famous drawing school founded by William Hogarth in 1735.

Drawing appears to have played a limited role in British artistic training before the eighteenth century, possibly owing to a limited supply of fine-quality paper. In an effort to improve this state of affairs and to compete with artistic education on the Continent, drawing schools were established across Britain. One of the first was Sir Godfrey Kneller's Academy of Painting and Drawing, founded in 1711. Following Kneller's example, British drawing schools were often private initiatives organized by local artist circles rather than national academies, as was the norm in France. The most famous was the St. Martin's Lane Academy at Slaughter's Coffee House in London, founded by the painter William Hogarth in 1735. British schools were also more egalitarian than their French counterparts, with classes taught and attended by practitioners of both the fine and applied arts. The general consensus in Britain was that everyone should learn to draw. "How absurd would it be," wondered Robert Campbell in his London Tradesman of 1747, "if the Workman could not give a sketch upon paper of the Design of the work?"

We do not know when and where Chippendale trained as a draftsman, but drawing clearly played an important role in his London workshop and was integral to the creation of the Director. In 1753 Chippendale joined forces with the printmaker Matthew Darly (ca. 1720–1780), who taught evening classes in drawing to tradesmen and young students. They selected from Chippendale's designs those to be included in the book and formatted the pages in meticulously drafted preparatory drawings, which were engraved by Darly and the brothers Johann Sebastian and Tobias Müller.

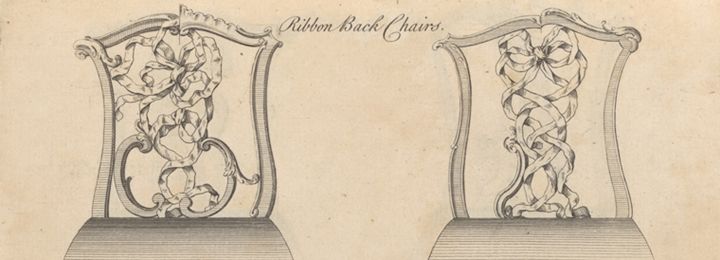

Remarkably, the majority of these superb preparatory drawings have survived, providing insight into the working process of Chippendale and his collaborators. The earliest, made about 1752–53, reflect the cabinetmaker's core business, from chairs, sofas, and beds to cabinets, tables, and bureaus. Designs for smaller objects and those with detailed carving, such as brackets, clock cases, and frames, were executed closer to the publishing date in 1754. Multiple designs are frequently offered on one sheet or even in a single design. The right side of a cabinet is sometimes depicted with elaborate carving, for example, while the left is shown unworked. Elsewhere, additional details convey how to execute small or otherwise hidden elements. Among the drawings connected to the third, expanded edition of the Director (1762), several are notable for their high level of finish and colorful washes, possibly made in response to those of Chippendale's young competitor John Linnell (1737–1796).

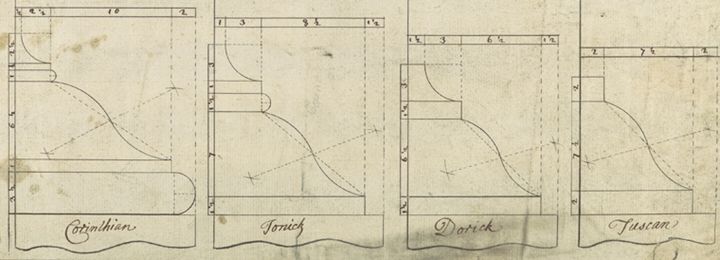

The furniture designs in the Director are preceded by plates detailing the proportions of the five classical architectural orders. With this introduction, Chippendale may have been responding to the contemporary concern for creating unity between a building and its interior rather than furnishing it with loose pieces in the latest fashions, as had been customary. He may also have been familiar with garden designer Batty Langley's book The City and Country Builders and Workman's Treasury of Designs (London, 1740), in which the author launched an assault against cabinetmakers in particular. Langley asserted that "Workmen of all Kinds (those called Cabinet Makers, only excepted) have in recent times greatly enjoyed the study of architecture," and warned cabinetmakers that they would soon be out of business if they chose to persist in their "stupid Manner."

Many cabinetmakers ordered Langley's book, either ignorant of the fact that they would be condemned in this manner or scared into following his instruction. By including the architectural plates in his Director, Chippendale cleverly thwarted accusations of this kind. Beyond being a defense of his craft, his designs reflect a thorough understanding of architectural proportion, particularly in the drawings and diagrams detailing silhouettes, measurements, and the curvature of domes.

Chippendale chose to self-publish the Director rather than sell his work to a publisher, which would have left him with little to no profit. To make sure his costs would be covered, he sold the book in advance through subscriptions. Beginning in the spring of 1753, he advertised his ambitious project, hoping to attract 400 subscribers at 1 pound 10 shillings for an unbound copy or 1 pound 14 shillings for a folio bound in calf leather. Although Chippendale had sold only 334 copies at the time of publication, interest must have exceeded expectations, as he issued the book in April 1754, four months ahead of schedule. Sales continued to accumulate, prompting the release of a second edition in 1755.

The Director owed its success in part to the formula Chippendale developed, which offered a range of designs to satisfy not just prospective clients and colleagues but, more broadly, the aspirations of the British nation. Chippendale's folio-size, encyclopedic publication was the first to elevate British furniture to the same level as Continental furniture, volumes of which already adorned the shelves of any well-appointed library. By adding quotations from Homer and Ovid to his title page and an explanation of the classic architectural orders, Chippendale sought to distinguish himself—and by association his peers in the merchant classes—as the equals of any "learned gentlemen." To own a copy of Chippendale's Director was thus to make a statement about one's ambitions in life.

Chippendale's own ambition comes to the fore most clearly in his decision to offer the third and expanded edition of the Director, published in full in 1762, in a French-language version. For the sake of expediency and cost-effectiveness, the title page and introduction were translated, but the inscriptions on the individual plates were left in English. More than providing an alternative to French design to his British clientele, Chippendale no doubt was also setting his sights on the Continental market. While the book was acquired by several important libraries, such as the French Royal Library and that of the Russian Empress Catherine the Great, Chippendale's furniture and designs remained most pervasive in the English-speaking world.

One of the great strengths of Chippendale's Director was that it offered a choice of furniture designs in three popular styles of the period: Modern, Chinese, and Gothic. Each had its own aesthetic and connotations, but all harmonized in their use of elaborate and imaginative carved decoration. Chippendale allowed readers to decide for themselves whether to choose a specific style for their furniture or mix and match at leisure.

During the reign of Louis XV of France, a taste developed for decorative forms based on natural motifs such as rocks, plants, and shells. The style became known as the genre pittoresque, or Rococo, and its ornamental vocabulary was quickly dispersed through French print series, aided by the emigration of Huguenot (French Protestant) artists and craftsmen to Britain. Chippendale would certainly have encountered the style in London, not least because many drawing teachers in Britain were of French descent and had enormous influence on young artists. While "French design" still represented sophistication to Chippendale's eighteenth-century audience, the British soon developed their own interpretation of the Rococo style, focused on detailed surface treatments of finely wrought leaves and exotic creatures.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, trade with the Far East supplied Europe and the American Colonies with exotic ceramics, textiles, and tea. These and other imports inspired local interpretations, often referred to as "Chinese" even though they incorporated traditions from several regions in Asia. Chippendale was not the first to create designs in the Chinese taste, but he wisely capitalized on the popularity of chinoiserie by hiring as his engraver Matthew Darly, who had just finished the comprehensive A New Book of Chinese Designs (1754). Chippendale's inclusion of the style in the Director led many to label any Asian-inspired furniture of the period "Chinese Chippendale."

British efforts in the eighteenth century to establish a national canon of art and architecture led to a rediscovery of English medieval treasures and a new appreciation for cathedrals, with their imposing spires and buttresses and complex drama of stained glass, grotesque stonework, and ecclesiastical altarpieces. The first edition of the Director (1754) contained twenty-four plates for "Gothick" furniture with fantastical interpretations of medieval architecture and design. In the third edition (1762), Chippendale added forty plates for Gothic beds, library furniture, and bookcases. The inclusion of Gothic tracery and architectonic details in Chippendale's furniture imparted a sense of authority and romantic fancy to domestic spaces such as libraries and bedchambers.

As the British Empire expanded in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries through maritime trade and colonization, the nation's material wealth increased exponentially, as did the size of the mercantile class, with its high social aspirations. Keenly aware of the lifestyle improvements taking place among his readership, Chippendale included in the Director designs for specialized forms to accommodate more lavish entertaining, dining, and dressing habits. He also provided designs for secretary bookcases, desks, and library furniture that would evoke a sense of professional respectability.

The success of Chippendale's Director inspired many other British cabinetmakers to publish their own series of prints and books with furniture designs. Some followed Chippendale's format closely. Ince and Mayhew, a competing London firm, went as far as to hire Matthew Darly, Chippendale's primary engraver, to execute the plates for their General System of Useful and Ornamental Furniture. Rather than publishing a complete book all at once, as Chippendale had done, they chose to market their designs in smaller editions called cahiers, which were delivered at regular intervals between 1759 and 1763. Other, more modest initiatives included Robert Sayer's Household Furniture in the Genteel Taste (1760), which brought together in one publication designs by various cabinetmakers, including Chippendale. The popularity of furniture books lasted only about two decades, however, as cabinetmakers soon realized that publishing their original but unpatented designs was not a sustainable business model.

For more than 250 years Chippendale's Director has played a leading role in British and American design, inspiring the longest-surviving furniture tradition in the Western world. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, nostalgic representations of Chippendale-style furniture transformed his work into a sacred relic of America's founding families and Britain's golden age. Prominent antiques experts and popular lifestyle magazines such as House Beautiful and Vogue fueled the acquisition of Chippendale-style furniture. Among designers, Chippendale's iconic status inspired tributes but also prompted ridicule from reformers and modernists trying to break from tradition.

Signature image: Attributed to Benjamin Randolph (American, 1737–1792). Side chair (detail), ca. 1769. Mahogany, northern white cedar, modern upholstery, 37 x 22 1/2 x 23 in. (94 x 57.2 x 58.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Sansbury-Mills and Rogers Funds, Emily Crane Chadbourne Gift, Virginia Groomes Gift, in memory of Mary W. Groomes, Mr. and Mrs. Marshall P. Blankarn, John Bierwirth and Robert G. Goelet Gifts, The Sylmaris Collection, Gift of George Coe Graves, by exchange, Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, by exchange, and funds from various donors, 1974 (1974.325). Related Content images: Thomas Chippendale (British, 1718–1779). Gothick [Gothic] Chairs (detail), in Chippendale Drawings, Vol. I, 1753. Black ink, gray ink, and gray wash, 7 13/16 x 13 1/2 in. (19.8 x 34.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1920 (20.40.1[22]) | Statue of Thomas Chippendale Sr. (detail) in Otley, England | View of the exhibition in gallery 752