For more than six decades, Iranian-born Siah Armajani (born 1939), who immigrated to the United States in 1960, has been captivated by the power of text and images to transform individuals' deepest held beliefs and understanding of their place in the world. The artist's practice can be explored in relation to what might be called an aesthetic of exile, one that makes space—real and conceptual—for the dislocated figure who is central to so much of the work. This exhibition traces the development of Armajani's art from his early days as a political activist in Tehran in the 1950s to his most recent work, a series of sculptures that directly confronts the refugee crisis unfolding around the world today.

The works on view combine a wide range of references: political propaganda, religious sermons, handwritten letters, magic spells, recited poems, songs broadcast on the radio, and architectural elements. As hybrid objects, they invite new readings and offer multiple perspectives. At the same time, they resist interpretation by blocking access, obscuring legibility, and frustrating conventions of use. These two apparently contradictory gestures are central to the experience of exile.

Created in Tehran in the 1950s, Armajani's collages on paper and cloth include references to pedagogical exercises that rely on the practice of copying. The artist describes his classes in penmanship: "The first line was done by a master and usually was: 'Father has this. Mother has that.' But mostly father. And we just follow." In addition to text, his collages contain details of works that he found reproduced in books on Islamic art. Similarly, the internal borders that define and divide many of the collages recall the conventions of the traditional Persian miniature. Elsewhere, pears and apples stand in for the still-life painting of the fruit bowl as a staple of a Western academic arts education.

These works are intentionally difficult to decipher even as they invite close study. Many incorporate wax seals or stamps from signet rings, as if to seal closed parts of the collage like a letter or talisman. Often, Armajani traces over lines of poetry or dictionary definitions, obscuring what was once legible. Likewise, calls for political change scattered throughout the works are partially hidden or disguised.

The artist borrows the phrase "follow this line," which appears in a number of the works, directly from a casual act of public vandalism. Children walking home from school, he recounts, would drag their pencils along the walls, claiming the public space as theirs and enjoining others to follow. At the same time, the phrase might be read as a critique of the status quo in Iran and the persistence of social and political inequalities through the approaches to thinking, speaking, and seeing taught in the classroom.

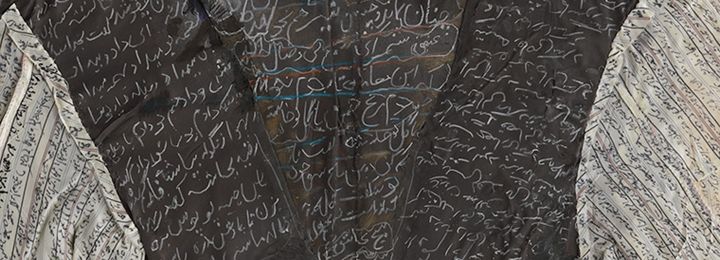

Siah Armajani (Iranian, born. 1939). Shirt #1 (detail), 1958. Cloth, pencil, ink, wood, 31 3/4 x 29 7/8 in. (80.6 cm x 75.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 2011 NoRuz at The Met Benefit, 2012 (2012.109). © 2017 Siah Armajani / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Beginning in the late 1960s, the motifs of the house and the bridge became central to Armajani's practice. In this period, the artist was familiarizing himself with nineteenth-century American farmhouses, bridges, and barns—structures built by artisans, carpenters, and joiners, rather than architects—which he described as "common-sense buildings." Armajani's treatment of these structures, and the common sense he ascribes to them, makes them appear both familiar and unfamiliar, that is—unheimlich (unhomely, or uncanny).

While the house represents a stable space for living, and the bridge is an archetype of movement and transition, the artist presents them as interchangeable. His houses block habitation and his bridges prevent crossings. In addition, their designs draw attention to the ways in which each structure defines a series of shifting spatial and temporal relationships: for example, above and below, or before and after. Both Armajani's homes and bridges create sites where none existed previously. Together, they form a "neighborhood" of relations.

Armajani associates letter writing with the figure of the scribe, whom he often observed stationed in front of the post office in southern Tehran. The scribe served the essential role of transcribing correspondence for a once largely illiterate population, while also selling talismans and spells. Writing and prayer tend to converge in these works, both representing forms of address or appeal.

Armajani identified his early collages as issues of a political broadsheet titled Rah-e Mossadegh (Mosaddegh's Way), in reference to the Iranian prime minister who was responsible for nationalizing the country's oil industry in 1952 and then ousted in a coup the following year. In pre-revolutionary Iran, the so-called night letter (shabnameh) was used to disseminate anti-establishment sentiments and news under the cover of darkness.

After Armajani moved to the United States, his writing migrated to the surface of the stretched canvas. He adapted techniques borrowed from the influential American avant-garde composer and artist John Cage to empty the works of subject matter. Instead of serving to transmit information, letter writing survived in Armajani's work of the period purely as gesture and form, or an address without a message.

Siah Armajani (Iranian, b. 1939). Written Iran (detail), 2015–16. Marker ink, colored pencil and graphite on Mylar, 42 1/16. x 223 3/8 in. (106.7 x 567.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 2017 (2017.246). © 2017 Siah Armajani / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In the 1960s, Armajani produced a series of works that present practical propositions or mathematical problems. Each relies on complex, often computer-assisted calculations for its resolution. In many, the artist set out to define the distance between two points in space or to model how to render three-dimensional space on the flat screen. He developed this approach in tandem with the construction of the Hybrid Computer Laboratory at the University of Minnesota in 1965 and the establishment, the following year, of Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), which aimed to foster collaborations between artists and their peers in the fields of science and engineering.

Armajani borrows the language of American space-age technology to sculpt, draw, or describe the relative distances between two points, creating pieces that trace in-between spaces. The results include a printout of an absurdly long number, a topographical map published in a design journal, and a series of computer-generated animations from 1970. The artist's hand has vanished entirely from these works.

Siah Armajani (Iranian, b. 1939). Architectural Entity Even Event (2): At One Moment Shadow-ful Area Equals Shadow-less Area (detail), 1970. Felt-tip pen on graph paper, 45 1/2 x 104 1/2 in. (115.6 x 265.4 cm). Walker Art Center, Minneapolis Art Center Acquisition Fund, 1971

Dictionary for Building is composed of approximately 150 small-scale architectural maquettes made with cheap and ephemeral materials; most of the models are on view in this gallery. In this key work, Armajani combines units of domestic architecture—doors, windows, gables, walls, chairs, and so on—to create improbable hybrid structures. These units abut one another in surprising and often nonsensical ways. In this manner, the artist renders the annexed elements useless in a conventional sense, while opening them up to new possibilities for meaning. The syntax of this lexicon of relationships relies on spatial prepositions (between, inside, in, on, under, above, by, next to) and opposing adjectives (front and back, closed and open). A later subset of models explores the typology of the stair or staircase. While empty of occupants, Dictionary for Building is replete with gesture and movement. The artist has returned often to this open-ended "dictionary" as a source for later works.

Armajani's lifesize reading rooms, gardens, gazebos, and bridges are designed to make visitors feel uncomfortable and alienated. What initially appear as inclusive spaces elicit feelings of confinement or exclusion when experienced firsthand. Drawing on a wide range of historical and architectural references, these structures acknowledge specific histories of class- and race-based oppression, as well as power differentials at play in our everyday built world. In these works, Armajani presents a vision of society coursing with antagonism rather than social harmony.

In 1999, Armajani turned away from creating outdoor installations, choosing instead to make sculptures encased in glass. "I have enclosed the sculptures so that people cannot enter," he stated. "Outside of these enclosed spaces, we are out of place, as though banished, estranged, expelled." The adjacent projection documents many works of public art Armajani has produced over the years. The models on view illustrate three archetypes—the bridge, the gazebo, and the Persian garden—that have informed his designs.

View a map of Armajani's public art in New York.

Armajani's deliberately awkward design for Sacco and Vanzetti Reading Room #3 includes references to the histories of violence toward racial and political minorities in the United States and early Soviet designs for popular education and entertainment. These diverse sources combine to produce prison-like structures that are also reminiscent of the modernist belief in the ability of architecture to embody and disseminate new, more just, models of society.

The work's title ties it to the Italian-American anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, whose execution for murder in 1927 was widely condemned as unjust scapegoating. Meanwhile, the diagonal, brass-colored slats attached to the side of one of the structures recall tobacco-drying racks that the artist saw on Southern plantations. Other elements evoke aspects of the Workers' Club designed by Russian Constructivist Alexander Rodchenko in 1925. While Rodchenko's Club conceived of leisure and education as collective activities that encourage participation in cultural and political life, Armajani's reading room tends to isolate and entrap its visitors. Another reference is Constructivist "street furniture" designed by Gustav Klutsis in the early 1920s with the aim of transforming passers-by into model Soviet citizens. Cheap and easy to transport, these objects included antennae and loudspeakers, platforms for orators, and projection screens for films. Likewise, many of Armajani's large-scale sculptures might serve as props or supports for a performance, broadcast, or recitation.

Visitors to this gallery in the exhibition are invited to take a seat, spend time with the reading material, and take home one of the pencils.

Siah Armajani (Iranian-American, born Tehran, 1939). Details from Dictionary for Building, 1974–75. Mixed media. Collection MAMCO, Geneva