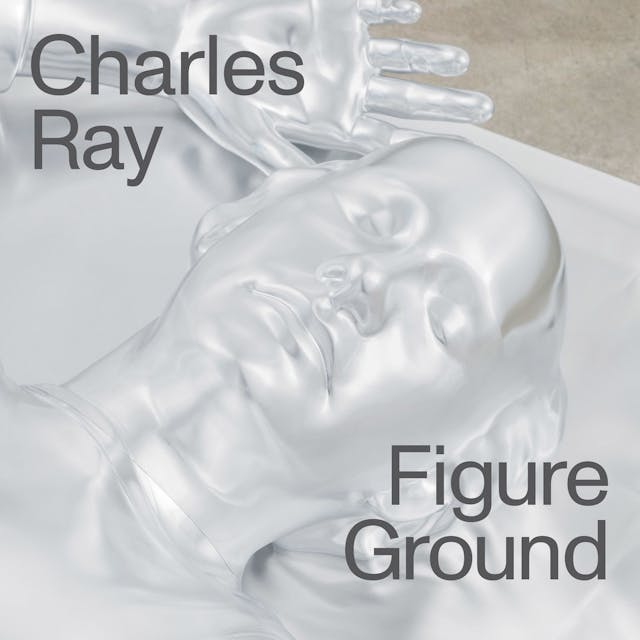

Charles Ray: Figure Ground

Charles Ray: Figure Ground

Introduction

For over five decades, Charles Ray (born Chicago, 1953) has experimented with a wide range of methods, including performance, photography, and sculpture, the medium for which he is recognized today. In the process, he has mined the tradition of Western art, mobilized the power of materials, and pioneered major advances in sculptural production, combining the analogue and the digital. Ray’s intriguing and occasionally bracing work addresses not only art history, popular culture, and mass media but also identity, mortality, race, and gender in sometimes provocative, often irreverent ways. Throughout, he has remained deeply invested in exploring the fundamental relationships between form and space, figure and ground.

Ray studied at the University of Iowa and Rutgers University, where he was exposed to a variety of artistic approaches, including modernist sculpture, intermedia arts, and process-based performance. In 1981 he moved to Los Angeles, where he continues to work today. Situated at The Met, whose collection the artist has long studied, Charles Ray: Figure Ground unites sculptures from every period of his career with key photographs from the 1970s to explore central aspects of his oeuvre. The works have been intentionally arranged in order to forge subtle connections between objects as well as between objects and viewers. Similar to a scholar’s stone, which is meant to facilitate and prolong thoughtful contemplation, Ray’s sculpture poses many trenchant questions but answers none directly.

The following Visiting Guide offers four points of entry for exploring the sculptures and photographs in Charles Ray: Figure Ground. Each one revolves around a different idea, approach, or technique animating Ray’s work across time and media. Any one piece might relate to multiple points of entry. We invite you to make connections by considering the material below.

“The pattern is where the sculptor’s work occurs.”

— Charles Ray, 2021

At the levels of both conception and production, much of Ray’s work relies on patterns and patterning. “Pattern” is a long-standing term in both sculpture and industrial production. In Ray’s case it refers to the clay, plaster, and fiberglass models that serve as the foundation for sculptures he later casts, carves, and machines. Many of the artist’s sculptures are also patterned on preexisting models, some concrete, others abstract, from novels, mannequins, and works of art to ideological formations like childhood and masculinity. When it comes to source material, Ray looks for patterns that embody the irreducible, “absolute manifestations of a culture,” Western and Euro-American culture especially. The readymades he draws upon are always subjected to reinvention, adulteration, recombination, and metamorphosis. The same holds true for his physical templates, which are part of a laborious process involving refinement over multiple steps, iterations, and materials.

Selected Artworks

View all“I needed to embrace not just what I could make, but what America could make and what America was. I returned to the river and to Twain.”

— Charles Ray, 2022, on making Huck and Jim for the Whitney Museum of American Art

Ray often revisits Mark Twain’s 1885 novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, considered an American classic. He references it directly in Huck and Jim (2014) and Sarah Williams (2021) as well as obliquely in Boy with Frog (2009). The sublimity of the natural world and the violence of racism play central roles in Huckleberry Finn. Set in antebellum Missouri and written during the waning years of Reconstruction, the book revolves around a fraternal but asymmetrical relationship between Huck, a poor White boy escaping an abusive father, and Jim, an enslaved Black man en route to the free states. Linked by their respective experiences of cruelty and their common desire for independence, Huck and Jim are friends, but by no means equals.

The novel’s many ambiguities and complexities, especially its unresolved position on slavery and prejudice, have prompted debate well into the twenty-first century. Author Toni Morrison once declared it both “troubling” and “amazing.” For his part, Ray translates the quintessentially American entanglements of Jim and Huck’s relationship into monumental sculptures. In both Huck and Jim and Sarah Williams, the paired figures are formally and optically entwined, just as they are ethically, politically, and structurally interconnected in Twain’s book. Each unit—each character—serves as figure to the other’s ground, as image to the other’s backdrop.

Selected Artworks

View all“Intentionality was the hand that fashioned this work from beginning until the end.”

— Charles Ray, 2015

Time and form intertwine in Ray’s sculptures, all of which emerged gradually, after long gestation periods and painstaking rounds of drafting, testing, and experimentation with differently scaled patterns in various materials. Every aspect of his sculptures, whether made in fiberglass, steel, or wood, is precisely articulated through the work of human and robotic hands. The artist often combines deep study of the philosophical and material conditions that have informed the making of art—from classical statuary to modernist sculpture—with an interest in the technical use and cultural significance of contemporary production methods. In the 1990s he incorporated commercial mannequin-making techniques, while in more recent years he has deployed industrial fabrication processes, such as the machining of aluminum and stainless steel.

Selected Artworks

View all“Space is the sculptor’s primary medium.”

— Charles Ray, 2006

Touch is central to Ray’s conceptual and material approaches to sculpture, especially the way he shapes space inside and around his works. “I see sculpture as using space, bending it, modeling it, manipulating it,” he has said. Whether in his small-scale pieces or his monumental works for civic sites, touch manifests through carefully calibrated points of contact between figures, objects, and the ground as well as through pointed gaps—rifts, hollows, and other voids. Ray is also sensitive to the tactile qualities of his material, be it machined steel, carved cypress, fired porcelain, or cast aluminum. The sculptures bear the trace of the many hands that work on them, from the human ones that chisel wood, model clay, or manipulate digital scans to the robotic ones that hew metal.