Introduction

"I laid out above eight pounds of my money for a suit of superfine clothes to dance with at my freedom."

—Olaudah Equiano, 1789

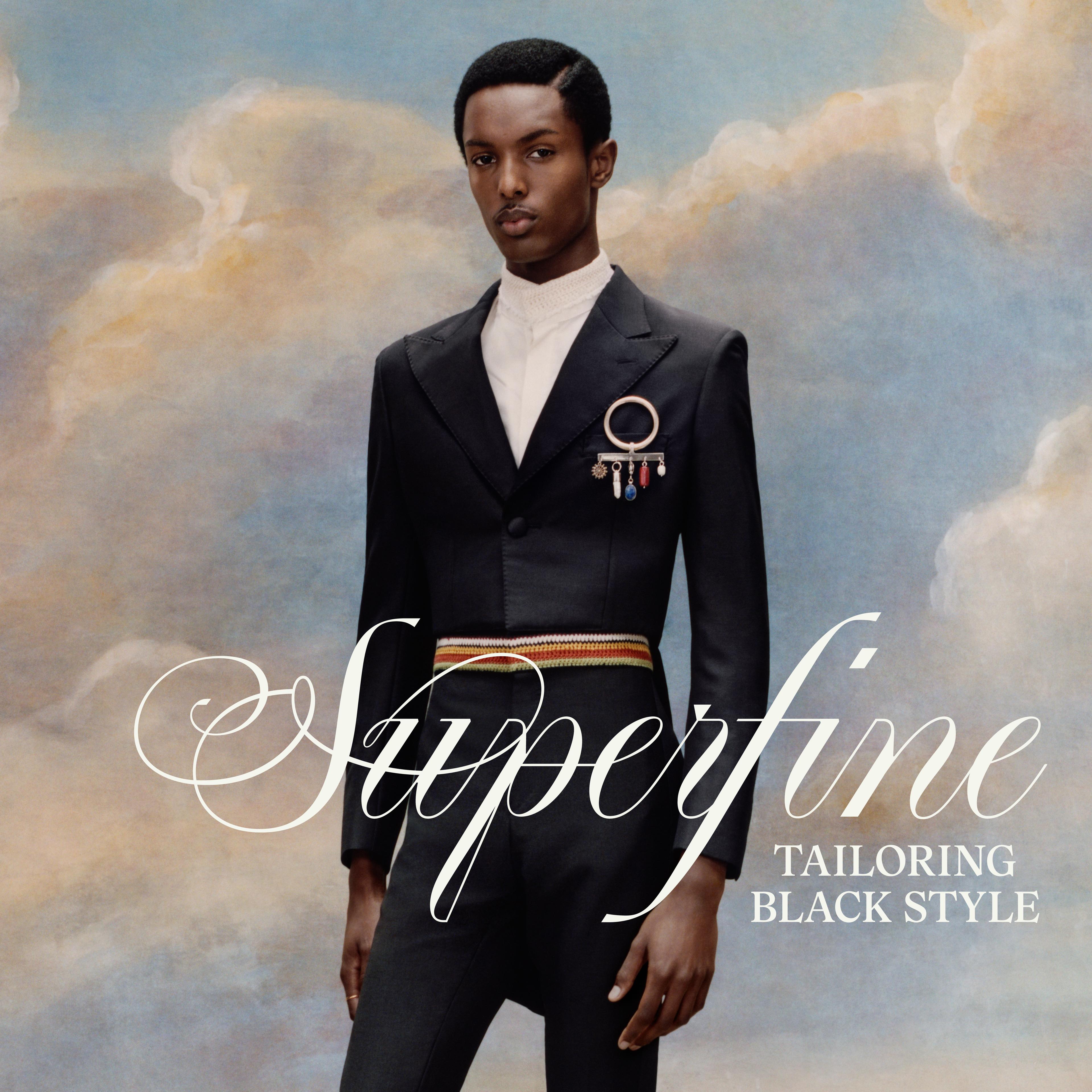

A dandy is defined as someone who “studies above everything else to dress elegantly and fashionably.” This impetus can be expressed in a range of ways, from absolute precision in dress and tailoring to flamboyance and fabulousness in self-presentation. Superfine: Tailoring Black Style presents a history of Black style through the lens of dandyism, emphasizing the importance of sartorial style to Black identity formation in the Atlantic diaspora and the ways Black designers have interpreted and reimagined this history.

Black dandyism, by and large engaged with by men, sprung from the intersection of African and European traditions of dress and adornment. Its history—from Enlightenment England to the contemporary art and fashion worlds of Paris, London, and New York—reflects the ways in which Black people have used dress and fashion to transform their identities, proposing new ways of embodying political and social possibilities.

The exhibition is organized into twelve conceptual and chronological groupings that build a specific, but not definitive, vocabulary of Black dandyism, exploring its complex history while also centering its playful experimentation and hopeful resistance. It features historical objects in a variety of media as well as garments by contemporary Black designers that tell stories about self and society inflected by race, gender, class, and sexuality. Throughout, dandyism is visualized as a vehicle of productive tension between being fashioned and fashioning the self.

Ownership

"Disembodiment. The dragon that compelled boys I knew, way back, into extravagant theater of ownership."

—Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me, 2015

“Ownership” explores dandyism’s relationship to currency and conspicuous consumption through the material signifiers of gold and silver, and through garments and accessories trimmed with or seemingly made from these precious metals. It highlights how clothing can dehumanize but also grant agency and self-possession.

In the eighteenth-century Atlantic world, a new culture of consumption, fueled by the slave trade, colonialism, and imperialism, enabled access to clothing and other goods that marked wealth, distinction, and refinement. Enslaved Africans were sometimes used as “luxury” servants by royalty, the aristocracy, and upstart merchants. As such, they were dandified, dressed in ornate garments that emphasized their objectification. Dandyism in turn became a mode for Black people to subvert this degradation by claiming and visualizing their own value and worth.

Histories of competing European and African valuation are represented here by the silver coin from sixteenth-century England known as the dandiprat, perhaps the origin of the term dandy, whose small size and value came to be associated with insignificance more generally. The dandiprat is juxtaposed with the “Kalinago Royal Coin #8” pendant by L’Enchanteur, a reimagined Indigenous currency from the Caribbean cast with the profile of an ancestor. By recontextualizing the material expressions of wealth and luxury, Black people today can “own” this history, using gold, silver, and other currencies to express self-esteem.

Presence

"She must have loved the idea of my presence, the combination of my looks, tall and honey colored; my impeccable manners and grooming; and my blossoming unorthodox style. Plus my master’s degree!"

—André Leon Talley on Diana Vreeland, The Chiffon Trenches: A Memoir, 2020

(In)famous in eighteenth-century London, Julius Soubise challenged society’s norms and expectations through his style and behavior. Born enslaved in the Caribbean, he was transported to England and lived with the duchess of Queensbury, where he was educated in the art of being a gentleman. Once emancipated, he became known for his pointed reworking of dandiacal style elements—outré fashion, fine accessories, and conspicuous grooming. His contemporaries recorded his antics in both text and caricature, emphasizing his love of expensive hothouse flowers and perfume.

At a time when Black people individually and collectively were negotiating their status as enslaved and emancipated, dandified men could convert their social invisibility to presence using their (sometimes outrageous) personal style. Soubise’s “flowering” as an individual, expressed through his comportment and association with the floral, is reflected in contemporary fashions and accessories that utilize floral motifs as signifiers of unabashed beauty and self-possession.

The bold, colorful, affirmative styling of modern dandies—an undeniable insistence on presence—is visualized by artist and aesthete Iké Udé, who lives and works in the tradition of dandyism. In both his art and life, Udé is an elegant man of fashion, using verbal and visual wit to make and leave a mark.

Distinction

"War gives numerous opportunities for distinction, and especially to those who in peace have demonstrated that they would be available in war; and soldiers can win distinction in both peace and war if they will but seize their opportunities."

—Henry O. Flipper, The Colored Cadet at West Point, 1878

Military dress symbolizes fastidiousness as well as political and cultural authority. Inspired by Enlightenment philosophy and the French Revolution’s emphasis on the “rights of man,” Toussaint L’Ouverture led a revolt by the formerly enslaved that resulted in the establishment of Haiti in 1804 as the first independent Black republic in the Western Hemisphere. Portraits of L’Ouverture (all imaginative, as none are known to have been made from life) in addition to those of fellow leaders and later Haitian presidents and emperors exude dignity, elegance, and distinction through their display of military dress.

The inheritance of masculine swagger and personal pride in revolutionary times is exemplified by celebrated French novelist and dandy Alexandre Dumas and his father, Thomas-Alexandre, the son of an enslaved Haitian woman and a French general of noble birth. Thomas-Alexandre fought in the French Revolution and was the first person of color to attain the rank of general in the French army. Portraits of father and son depict their stylish confidence, passed down as a proud legacy.

Similarly, Black nationalist movements across the diaspora, including Marcus Garvey’s Back to Africa movement, Ethiopian independence, and the Black Power movement in the United States, all had distinct sartorial expressions. These styles have been highlighted, exaggerated, and sometimes deconstructed by contemporary designers who visualize and question the association of power, militarism, and masculine elegance.

Disguise

"Just before the time arrived, in the morning, for us to leave, I cut off my wife’s hair square at the back of the head, and got her to dress in the disguise and stand out on the floor. I found that she made a most respectable looking gentleman."

—William Craft, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom; or, The Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery, 1860

Dress can disguise or reveal, especially for those negotiating the fraught line between subjugation and liberation. Dandyism enabled the enslaved and emancipated to convey the ways that identity is dependent on—and manipulated by—sartorial conventions.

As seen in “runaway” advertisements, people escaping enslavement understood that clothes communicate social hierarchies and denote people both as individuals and as members of undifferentiated groups. Some absconding people escaped with wardrobes of clothing that they used to disguise themselves and to fund their journeys to freedom. When enslaved couple Ellen and William Craft ran “a thousand miles for freedom,” Ellen passed as white, male, and upper class, while William pretended to be her loyal Black male servant with the aid of a dandiacal disguise.

Just as dress can be a form of concealment, it can also reveal a true self. In the early and mid-twentieth century, Ralph Kerwineo and Stormé DeLarverie donned typical male attire as a manifestation of their gender-nonconforming identities and sexualities, a gesture that was as much a means of survival as self-expression. The contemporary garments featured here all convey the transformative role of fashion in dressing across the boundaries of race, gender, sexuality, and class.

Enslavers placed classified advertisements for absconding enslaved people in local newspapers from colonial times to the end of the Civil War, sometimes offering generous rewards for their return. Some of these ads are remarkably detailed, including precise descriptions of the clothing, grooming, and comportment of Black self-emancipators. Some runaways were described as “excessively fond of dress”; taking fine clothes with them, they endeavored to pass as white, free, and/or of a higher class. In 1850 the Fugitive Slave Act demanded the return of runaways, even if they had reached a free state, increasing the danger of escape and precariousness of self-liberation.

Freedom

"I’ll tell you what freedom is to me: no fear. I mean really, no fear . . . like a new way of seeing something."

—Nina Simone, Nina: A Historical Perspective, 1970

“Freedom” explores the anxieties about Black social mobility that coalesced around issues of dress and comportment in the decades before the Civil War. From the 1820s, successful Black men, some of whom had been free for generations, adopted bourgeois dress and manners to express their social and political ambitions. They sat for commissioned portraits that communicated their wealth, power, and self-assurance via their stylish, refined clothing and impeccable grooming.

The moment these men gained prominence, they were satirized and stereotyped. A new representational regime, the blackface minstrel show and related caricatures, emerged to mock and vilify this striving for equality and citizenship. Together, they attempted to assert a fundamental incongruity between being Black and being fashionable, with fashion as a stand-in for freedom.

Several works here, however, defy these new forms of white racism. The stylish Black couple in the Philadelphia Fashions portrait, accustomed to societal judgment, turn their critical gaze on those that would denigrate them. The cakewalk, a high-energy dance that was a feature of the minstrel show, seemingly mocked Black pretensions to fashionable society. However, the dance was actually appropriated from a satire of white slaveholders by the enslaved. When Black folks danced the cakewalk, they critiqued the blackface caricature, creating a liberating and joyous celebration of the power of Black expressive culture.

Champion

"Have pride in the way you dress, the way you talk, the way you walk, the way you carry yourself. Discipline is the thing that makes you a champion."

—Walt Frazier, “Walt ‘Clyde’ Frazier Is Still the NBA’s Greatest Style God—and He Knows It,” GQ, October 6, 2016

For Black men, athletic success has often been a route to both physical and fashionable distinction. Today, elegant and conspicuously colored, patterned, or accessorized clothing worn by athletes has become an indelible part of the entertainment value of sports. This form of Black dandyism distinguishes athletes as astute and visible tastemakers, often positioned at the nexus of sports and capitalism.

In the field of horse racing, Black jockeys found success until they were forced out of the sport in the early twentieth century. Enslaved Black jockeys often wore uniforms, or “silks,” that matched the livery of their enslavers, and both enslaved and emancipated jockeys frequently celebrated their success sartorially, dressing up in the highest fashions of the day. Boxers such as Jack Johnson and Muhammad Ali also lived extraordinary lives that challenged the boundaries of race, affording them avenues to fashionability not readily available to others. Likewise, from the time of legendary New York Knick Walt Frazier’s heyday in the early 1970s to now, basketball players have been sharp dressers and shrewd entrepreneurs, more recently using the NBA tunnel as a fashion runway.

As seen here, contemporary designers have elevated sports and athletic wear through historical references and experiments with form, resulting in garments that cover the body as well as some that reveal and revel in its musculature.

Heavyweight Champions

The fame and notoriety of legendary boxers are often reinforced by their fashionability. Jack Johnson and Muhammad Ali were both known for their physicality and appearance in and out of the ring. In 1910 Johnson, the “Galveston Giant” and first Black Heavyweight Champion of the World, famously knocked out boxer James Jeffries, known as “The Great White Hope,” which led to riots across the country. Johnson broadcast his success through his connoisseurship of clothing, cars, and controversy, living a life of luxury and extravagant style that provoked public ire for, among other things, his marriages to white women.

Muhammad Ali, known as “The Greatest,” similarly challenged racial regimes and social hierarchies. His career as a boxer and his efforts as a civil rights activist are unparalleled, and he conducted both with style. In their satiny texture and black-and-white color scheme, Ali’s signature Everlast shorts were a nod to the formalism of a tuxedo, while outside the ring he enjoyed wearing bespoke suits.

Respectability

"True enough, we think a man is wanting in the upper story, who invites attention to his fine clothes; but a man is wanting, both in the upper and lower story, when he pays no attention to his dress. . . . The respectability and dignity of colored Americans must be upheld."

—Frederick Douglass, “There Is Something in Dress,” Frederick Douglass’ Paper, May 25, 1855

Black political and cultural leaders have long understood the power of dress to communicate pride and command respect. Wearing a bespoke suit asserts a particular form of arrival and ambition. The freeborn, self-taught scientist Benjamin Banneker defended both his almanac (below) and his reputation in the 1790s through impeccable research and self-presentation. Frederick Douglass exuded dignity with a sartorial elegance that was as impactful as his rhetoric in defense of Black humanity during the Civil War and Reconstruction. One of the best-educated Black men in the early twentieth century, W. E. B. Du Bois wore tailored suits while expounding Black pride and progress.

Tailoring traditions were often passed down within families in the African diaspora. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, students could also learn these techniques at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs)—centers of leadership, culture, and fashion. Master tailors such as Andrew Ramroop, designers like Jeffrey Banks, and style icons such as André Leon Talley have continued to demonstrate that the impeccable, well-made suit endures as a form of pride and protection.

Jook

"All night now the jooks clanged and clamored. Pianos living three lifetimes in one. Blues made and used right on the spot. Dancing, fighting, singing, crying, laughing, winning and losing love every hour. Work all day for money, fight all night for love."

—Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God, 1937

From the time of emancipation to the Harlem Renaissance, jook (or juke) joints, speakeasies, and cabarets were places where exuberance was expressed and embodied sartorially. Entertainers and patrons alike dressed in refined and racy ways, “lookin’ good” for themselves and each other. Avant-garde fashion often aligned with a desire to push the boundaries of race, gender, class, and sexuality through fine and flashy clothing.

The zoot suit required a surplus of fabric to create its sharp-shouldered, oversize shape, which amplified the wearer’s svelte silhouette. Worn by “hepcats” like jazz musician Cab Calloway, the zoot suit was a symbol of transgression, joy, and youth in its rejection of traditional tailoring. It became the symbolic instigator of “riots” in the 1940s when Black, Chicano, and Filipino youth clashed with servicemen critical of their attire. The zoot has more recently been refashioned by Latine designers interested in recontextualizing its provocative, “outsize” power for the twenty-first century.

Like the zoot, the tuxedo is provocative and multifaceted. Worn by both service workers and the well-heeled at formal functions, it is at once a uniform and a garment of distinction. When donned by blues singers and cabaret performers, the tuxedo has been used to communicate an unapologetic sex appeal, a sharp-edged androgyny, and a playful yet assertive queerness.

Heritage

"Heritage is so complex that we have to be simple. And we have to consider ourselves global. It takes a lot of courage to do that."

—Maya Angelou, “A Way Out of No Way,” African American Lives 2, February 6, 2008

Fashion can bridge gaps in diasporic history, as clothes are able to relay personal stories and explore familial histories essential to building self-confidence and a sense of belonging. On the African continent and in the diaspora, Black dandyism has a long history of hybridizing regional and national forms of African dress with Western tailoring traditions.

Cultural exchange and negotiations of political and social hierarchies during the time of enslavement, colonialism, and imperialism could be seen in outfits that remixed dress conventions in creative and unpredictable ways. Decolonization also encouraged people of the African diaspora to sartorially signal their political support of and cultural resonance with Black and African liberation movements. Since the 1960s, people in the African diaspora have worn clothing with African motifs and themes as a point of pride and connection.

Designers of African descent often reference their diverse heritages and personal journeys in their work, frequently taking inspiration from and amplifying forgotten or overlooked histories of Black people in the process. Virgil Abloh incorporated the draped forms of traditional Ghanaian garments in both suiting and streetwear, while Emeric Tchatchoua, Samuel Boakye, and Jacques Agbobly use color and pattern derived from African textiles to enliven their designs.

Beauty

"Beauty is not a luxury; rather it is a way of creating possibility in the space of enclosure, a radical art of subsistence, an embrace of our terribleness, a transfiguration of the given. It is a will to adorn, a proclivity to the baroque, and the love of too much."

—Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals, 2020

In 1968 Nikki Giovanni wrote a poem in praise of Black male beauty that begins loudly and proudly with the lines “i wanta say just gotta say something / bout those beautiful beautiful / beautiful outasight / black men.” These men were defined by the chic spectacularity of their fashion and grooming, and their “fire red, lime green, / burnt orange / royal blue” clothing intensified their desirability. Touting the “brand new pleasure” that she and others took in their appearance, she praised the confidence they exuded and the fabulousness of their style and stances.

During and after the civil rights and Black Power movements as well as the sexual revolution and gay and lesbian rights movements of the late 1960s, Black men gained social visibility with a form of radiance that relied on pride and panache. This cultural confidence and interest in self-regard allowed for an experimentation with unconventional modes of masculine dress.

“Beauty” transitions from historical and contemporary fashions that radiate light to those that are saturated with color. Featuring drapery, lace, ruffles, and sequins, the garments also emphasize Black dandyism as a mode of dress that approaches and appropriates femininity as part of its transgressive power.

Cool

"Being rebellious and black, a nonconformist, being cool and hip and angry and sophisticated and ultra clean, whatever else you want to call it—I was all those things and more."

—Miles Davis, Miles: The Autobiography, 1989

In the latter half of the twentieth century, Black designers and style leaders were at the center of redefining how men dressed and showed up to work and play. This turn to exquisitely styled casual dress revolutionized menswear. Featuring khaki, denim, tracksuits, and knitted cardigans, this relaxed and easeful form of Black dandyism sartorially communicated “cool”—an undefinable concept produced when fashion and accessories, posture and movement come together, attracting notice and producing desire.

“Cool” takes its inspiration from the Kariba suit, which became popular with politicians in the formerly colonized islands of the Caribbean in the early 1970s as a symbol of their adaptation of and freedom from European traditions. The self-styling of jazz musicians and hip-hop artists—depicted, respectively, in Art Kane’s 1958 photograph Harlem and Gordon Parks’s 1998 remix, A Great Day in Hip Hop—bookend this moment. Jazz musicians adopted styles of casual collegiate elegance, while in the 1980s the luxury-label-inspired and branded apparel of celebrated designer and stylist Dapper Dan came to define hip-hop style. Contemporary designers pay homage to these now-canonical modes with fine materials and couture-like construction techniques.

Cosmopolitanism

"In the world in which I travel, I am endlessly creating myself."

—Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, 1952

In their clothing and manners, those practicing dandyism visualize membership in an interconnected, sophisticated, cosmopolitan world. Migration and movement, whether forced or chosen, imagined or actual, has transformational power. “Cosmopolitanism” focuses on travel and the crossing of geographic and symbolic boundaries between and within Africa and its diaspora.

Travelers carry dreams in their luggage. With a bag and pilot-uniform-inspired ensemble, the artists’ collective Air Afrique, collaborating with Pharrell Williams of Louis Vuitton, pays homage to the airline of the same name that connected African nations. André Leon Talley’s Louis Vuitton luggage reflects his success journeying from the American South to the fashion capitals of Paris, Milan, and London. Liberian American Telfar Clemens’s branded Carry Bags are a more portable and pliable alternative, made in the spirit of accessibility.

Savile Row tailor and fashion designer Ozwald Boateng regularly crosses between cultures and continents as he brings British tailoring to a global audience, emphasizing garments precise in fit and silhouette and rendered in his signature bright colors. Foday Dumbuya of Labrum London follows in Boateng’s footsteps, with his “designed by an immigrant” ensembles embodying the transcendent possibilities of movement across the globalized world.

Outro