The Tudors and their courtiers surrounded themselves with art—from the furniture they used, the books they collected, and the jewelry they wore. While these works span dramatic differences in scale and medium, one aspect they all share is that they were meant to be moved and to be handled. This fitted the fast pace of their owners’ lifestyles, which were filled with flurries of activity like readying palace interiors for entertaining. Conversely, these objects also offered moments of calm, contemplation, study, and introspection.

Dismantling the Sea-Dog Table

This banqueting table exemplifies the spectacular European design Tudor courtiers enjoyed. It was made in France at the request of English Countess Bess of Hardwick and her husband, Lord Shrewsbury. After their marriage floundered, Bess took the table with her, subsequently moving it to the magnificent new home she built at Hardwick Hall. The table’s most astonishing feature is the way it can be quickly and smoothly taken apart into seventeen separate elements making for easy movement around and between its wealthy owners’ different properties. Tudor England entertained at a demanding pace, with feasts and festivities taking place throughout the year to honor religious holidays, as well as the expectation that every good host should welcome guests and visitors with multi-course banquets. Spreads of rich pies, whole fishes, and spit-roasted beast and fowl, were succeeded by colorful arrays of marzipan, pastries and sweetmeats, flavored and colored by spices and dried fruits imported from across the globe.

Hanging the Troy Tapestry

The Tudors loved how tapestries could tell stories at a monumental scale within their palaces. Pliable and portable, these massive textiles woven in the Southern Netherlands clothed bare walls, bringing insulation, texture, and color to royal and noble homes. Keeping up with the movement of the court, the staff of the Great Wardrobe—a royal department responsible for furnishings—continuously installed and deinstalled tapestries. These great wool and silk images shifted between different palaces, rolled up and transported by horse and cart. Watch The Met’s Textile Conservators install a tapestry depicting the Trojans preparing for war, from the Story of Troy series, likely originally owned by Henry VII.

Using the Astronomicum Caesareum Book

With its hand-colored illustrations, this splendid book is a feast for the eyes just to leaf through. But it was designed and marketed to meet a specific function: detailed instructions explained to privileged owners—amongst them Tudor King Henry VIII—on how to turn the paper dials according to dates and star signs, to create their own astrological charts and forecasts. Sixteenth-century royalty and scholars alike combined the desire to expand scientific knowledge with long-held superstitions that it was possible to predict anything from one’s health, to the weather and ideal moments of susceptibility—or conversely, obtuseness—according to the movement of the stars.

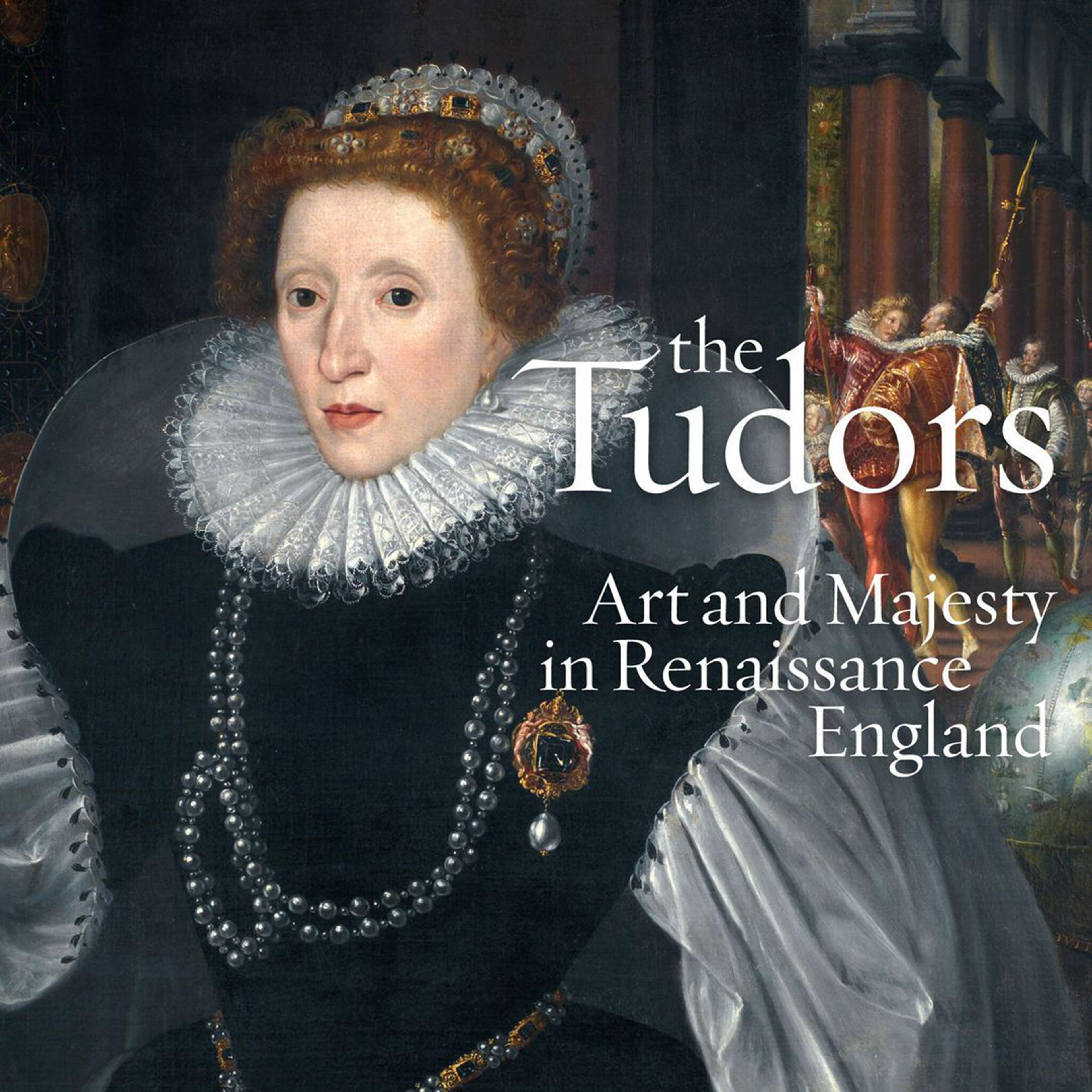

Opening the Heneage Jewel

The innovative painting of miniature portraits flourished under the Tudors—sharing a beloved’s facial features on a significantly exclusive and intimate scale. Designed to be worn on the body and examined in hand, this locket capitalized on the precious reveal of Queen Elizabeth I’s features, nestled within an enameled, jewel-encrusted golden case. Celebrating and pledging fidelity between monarch and loyal subject, the Heneage Jewel was likely made as a gift either to Elizabeth or to her favored courtier, Sir Thomas Heneage. As such, it doubled as both a private art work, destined for a limited and elite audience, and as a public declaration of loyalty and favor.