Visiting Guide

Introduction

580. Introduction

NARRATOR:

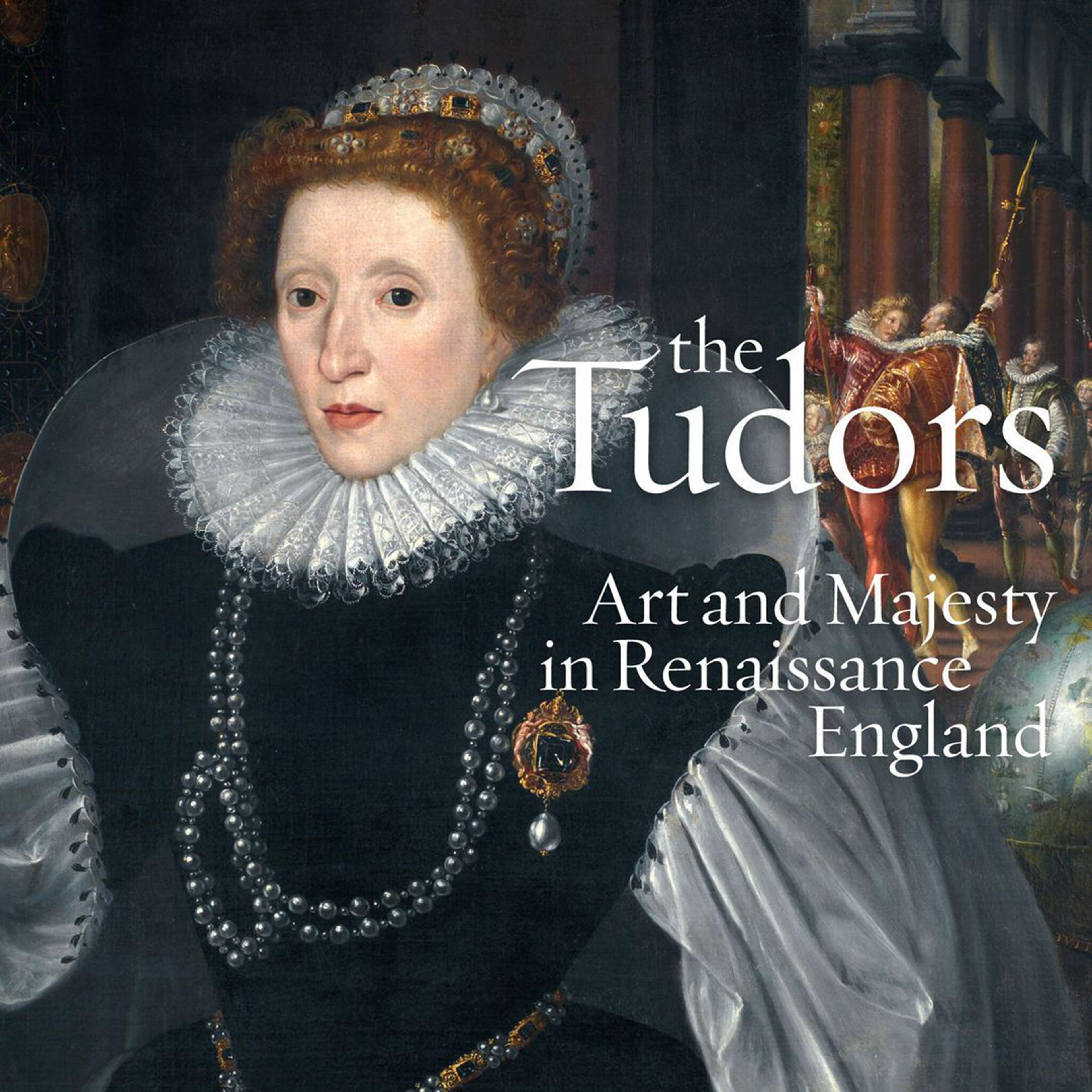

Welcome to The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England.

The year is 1485. Henry Tudor has just seized the throne of England. Henry’s enemies describe him in damning terms:

VOICE 1:

An unknown Welshman whose father I never knew…

NARRATOR: And another referred to Henry Tudor as...

VOICE 2:

Captain of rebels and traitors, descended of bastard blood…

NARRATOR:

But Henry’s new dynasty gained recognition from the world; and it achieved this partly through the magnificence of its art.

ELIZABETH CLELAND:

I'm Elizabeth Cleland and I'm a curator in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

One of the things that's so compelling about the Tudors is that they really knew how to use art to project and craft this incredible impression of majesty.

ADAM EAKER:

Hi, my name is Adam Eaker. I’m an associate curator in the Department of European Paintings.

We want to present the Tudor courts as a center of Renaissance innovation and patronage. And introduce our visitors to the incredibly engaging and colorful personalities of this court.

NARRATOR:

And you’ll hear the voices of some of those personalities, in their own words, from first-hand historic accounts from the Tudor period.

This Audio Guide is sponsored by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

###

Though the Tudor dynasty ruled for only three generations, it oversaw the transformation of England from an impoverished backwater to a major European power operating on a global stage. The dynasty emerged from the devastation of the Wars of the Roses, which ended in 1485 when Henry Tudor seized the throne. The second Tudor monarch, Henry VIII, brought about England’s break with the Roman Catholic church, while his daughters, Mary I and Elizabeth I, were the first two women to rule the country in their own right.

Painfully aware that their claim to the throne was tenuous and that the prospect of a return to civil war loomed around every corner, the Tudor monarchs devoted vast resources to crafting their public image as divinely ordained rulers. At times guilty of religious intolerance and violence themselves, the Tudors benefitted in their pursuit of the finest tapestries, books, paintings, and armor from religious wars on the European continent that periodically drove waves of talented artists to seek safety in England.

This exhibition evokes the richly layered interior of a Tudor palace in order to explore the remarkable art of the English Renaissance. At the same time, it reveals the high political stakes of Tudor patronage and the cosmopolitan world of artists and merchants who served the court.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Inventing a Dynasty

581. Portrait of Henry VII, Unknown Netherlandish Painter, 1505

NARRATOR:

From the day Henry Tudor seized power and became Henry VII, he had a thorn in his side. Related to the English royal family through illegitimate lines of descent, he’d need to secure his place on the throne in order to pass it on to his descendants. This portrait played a part in that plan.

You may be surprised that – for a royal portrait – it’s modest in size. That’s because it was designed to travel. Henry was 48 when it was painted. His wife, Elizabeth of York, had just died. He needed a new bride—one from a European dynasty, and so he sent this portrait to the Habsburgs, a lineage much more prestigious than his own. Curator Adam Eaker.

ADAM EAKER:

It was about recording the facts of physical appearance and physical health, really – when you think about this as a portrait that’s part of a marriage negotiation – showing that Henry is not sickly, he’s not elderly, he really is a viable bridegroom. Because dynasties at this period were obsessed with begetting heirs.

NARRATOR:

But the portrait had to convey more than just a likeness: it had to establish his status and credentials. Notice the red rose he holds – the symbol of his royal Lancastrian ancestors. And the gold chain, with its sheep’s fleece hanging from the center: this symbol proclaims Henry as a member of a highly exclusive European order of chivalry, the Order of the Golden Fleece. So, the portrait served as a way of sending a long-distance message.

ADAM EAKER:

That he’s worthy, that he’s a peer, he’s a European monarch whose claim to the throne is secure, and also in a certain sense that he’s attractive. Maybe not physically the most dashing or prepossessing person, but that he’s wealthy, and that he also has a certain standing.

Playlist

Henry VII spent prodigiously to impress his subjects and assert his right to the throne he had seized by force. With an eye to solidifying international relations, he negotiated royal marriages for his children abroad, hosted foreign diplomats, and did business with Flemish art dealers and Italian bankers.

Surpassing his father’s ambitions, Henry VIII claimed supreme authority over both church and state. Infamously married six times, his decision to divorce Katherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn led directly to England’s departure from the Roman Catholic Church. In the wake of this breach, he continued to use artistic patronage to promote his status as a peer of Europe’s other monarchs, even as some scorned him as a heretic.

The brief reigns of Henry VIII’s son, Edward VI, and of his eldest daughter, Mary I, epitomized the religious strife of the sixteenth century, with Edward a devout Protestant and Mary ardently committed to the Catholic faith. Their Protestant half-sister, Elizabeth I, by contrast, achieved a long reign of peace and prosperity, while still facing constant threats of foreign invasion and depending on a vast surveillance state. Maintaining strict control over her public image, she oversaw the emergence of a distinct Elizabethan style centered on the glorification of the queen herself.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Splendor

584. Sea Dog Table, After Jacques Androuet Du Cerceau, 1570

NARRATOR:

Tudor monarchs surrounded themselves with furniture and art from Europe and beyond, and their richest courtiers followed suit.

This carved and inlaid French table was used in Hardwick Hall, one of the great country houses of England. It would have staggered visitors with its opulence, whimsical design, and technical innovation.

ELIZABETH CLELAND:

The Sea Dog Table is just one of those incredibly rare survivals.

NARRATOR:

Curator Elizabeth Cleland.

ELIZABETH CLELAND (continuing):

We have very little bespoke furniture from the sixteenth century surviving, so this gives us a sense of what we’re missing. It’s a glorious combination of color and detail and texture. When you look up close you can see there are a few traces of the original gilded silver ornamentation. There’s the color of the inlaid marble set in the tabletop.

NARRATOR:

Perhaps most striking, though, are the so-called “sea dog” beasts supporting the tabletop.

ELIZABETH CLELAND:

They’ve got these scaly reptilian bodies, fishy fins, and then these very endearing dog’s heads. None of them are the same; some of them have their mouths open, some of them have their mouths closed. And they’re completely mythical, fantastical beasts.

But I think what’s also great about this table is not just the fantasy and the inventiveness of the design. Perhaps the most incredible fact of all is that the whole thing can dismantle into seventeen different elements to be easily handled and transported and moved from room to room. Because that really was a key element of life in a Tudor great house or palace—this ability to move from space to space with the court and with the celebrations.

###

Playlist

Tudor palaces and grand houses featured a range of specially demarcated spaces, from great halls for feasting and long galleries for strolling and discreet conversation to intimately scaled cabinets or “closets” for prayer, privacy, or the close contemplation of works of art. Contemporary inventories, paintings, and descriptions can help re-create these splendid interiors, most of which have long vanished.

Figurative plasterwork, decorative textiles, gleaming metalwork, and the richly dressed bodies of the courtiers themselves created a dazzling effect of overlapping surfaces. As monarchs traveled between residences, portable furnishings transported their splendor with them. Goldsmiths’ work filled credenza displays, while tapestries woven in richly dyed wools, silks, and metal-wrapped threads enveloped rooms, blurring the boundaries between actual and imagined space. In private chapels, privileged users contemplated devotional manuscripts and images, a practice eventually rejected by Protestant reformers. Games, musical instruments, and athletic tournaments all provided opportunities for ostentatious recreation.

The objects in this section speak to the Tudor monarchs’ support of local artists and newly arrived Flemish and French immigrants as well as their taste for luxurious imports, including Chinese porcelain and Indian mother-of-pearl acquired from Asian artists and merchants via increasingly globalized networks.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Public and Private Faces

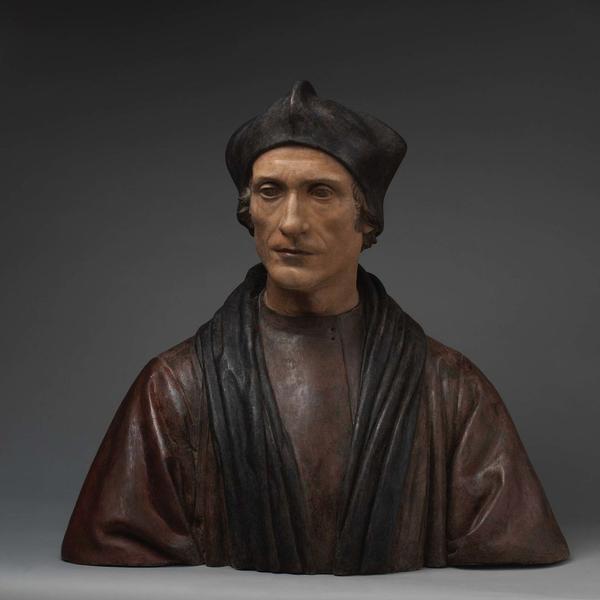

586. Bishop John Fisher (1469–1535), Pietro Torrigiano, 1510–1515

NARRATOR:

In this section, we come face to face with some of the extraordinary personalities of the Tudor period – like this terracotta bust of John Fisher, the Bishop of Rochester. He was a stern critic of decadence and extravagance. He once said:

MALE VOICE:

Truly, most reverend Fathers, what this vanity in temporal things worketh in you, I know not…

NARRATOR:

Fisher was a scholar and an important figure in the Church during the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII.

MALE VOICE:

I perceive a great impediment to devotion in attending after triumphs, receiving of ambassadors, haunting of princes’ courts, and such like ways.

NARRATOR:

Florentine sculptor Pietro Torrigiano captures some of Fisher’s charisma.

Elizabeth Cleland.

ELIZABETH CLELAND:

I think we can really share the amazement that Tudor courtiers felt when they experienced Torrigiano’s work for the first time. It’s just so incredibly lifelike. There’s this sense of arrested movement; if you turn away, he’s going to move his head. Those tiny curls around his ears: one can really believe that they cover his whole head—that they’re underneath that scholar’s cap.

It’s as if he’s captured a little bit of his soul. The way he’s modeled in terracotta: you’ve got the stern set of his mouth, and the slightly furrowed brow. He was a man who really prided himself in keeping to his principles, and I think we get a sense of that, looking at the bust.

NARRATOR:

Fisher’s principles cost him dearly. When Henry VIII broke with the Church of Rome, Fisher could not bring himself to support the king.

ELIZABETH CLELAND:

The pope, trying to draw attention to his plight, names him cardinal, and then Henry’s reaction is: Okay, then I’ll send his head to Rome to receive his cardinal’s cap. He doesn’t quite do that, but he does have him publicly executed. So, the glories and the beauty of the Tudor period, but also the horror and the violence, I think are encapsulated right here in this bust.

###

Playlist

Portraiture dominates the surviving record of Tudor painting. Most people in sixteenth-century England would have found the idea that a portrait should offer insight into the sitter’s personality or character surprising. Such paintings were instead commissioned as records of status, lineage, piety, and political affiliation as well as physical appearance. At a time when travel was difficult, they allowed far-flung relatives to keep in touch across long distances or prospective royal spouses to gauge the attractiveness and health of a future bride or groom. The emergence of the portrait miniature, intended to be held in the hand or worn on the body, heightened the association between portraiture and intimacy as well as the bridging of geographic separation.

German-born painter Hans Holbein the Younger was a key figure in the transformation of this genre during the reign of Henry VIII. Initially working for a clientele of German merchants and humanist scholars, he soon attracted the attention of the English court with his unparalleled technical mastery and ability to capture a likeness, for which he used preparatory drawings made from life. He also served the court by producing designs for metalwork and other works of decorative art.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Languages of Ornament

589. Armor Garniture of George Clifford (1558–1605), Third Earl of Cumberland, Made under the direction of Jacob Halder, 1586

NARRATOR:

This highly decorative, gilded armor was designed as a display of loyalty to the queen. It was made for George Clifford, the young Earl of Cumberland. Soon after, Cumberland was appointed as Elizabeth’s official Champion at her Accession Day tilts. At this annual event, jousting and tournaments were held at the court to celebrate the coronation. Curator Elizabeth Cleland.

ELIZABETH CLELAND:

Elizabeth and her courtiers really develop this idea of Elizabeth as the Virgin Queen with her group of loyal, valiant knights who would fight to the death to protect her. It’s returning to the idea of Arthurian romance, and it’s making a virtue out of what politically was a bit of an issue, that Elizabeth refused to marry; that there was no Tudor heir to the throne.

NARRATOR:

Medieval chivalry was among a broad range of sources the Tudors drew on to create their distinctive artistic style.

ELIZABETH CLELAND:

I think it is the Elizabethan notion of chivalry embodied. We can almost imagine his body still inside the armor. And he is literally enveloped with Elizabeth’s emblems: there’s no doubt whose champion he is. We can see so many different heraldic devices here. The Tudor rose, of course. The fleur-de-lis, which is a nod to England’s increasingly sanguine claims to the French throne as well. We can see Cumberland’s own device of annulets or small rings. And within the knotwork patterns, there’s Elizabeth’s device of back-to-back Es. They’re a little harder to make out, but there’s one right in the center of Cumberland’s chest, and there’s another in a heart shape just below his neck.

NARRATOR:

It would have been an immensely costly commission. Cumberland’s daughter later reported of her father:

FEMALE VOICE (initially proud, then turning to bitterness):

In the exercise of Tilting, he did excel all the Nobility of his time. All such expensive sports did contribute the more to the wasting of his estate….

###

Playlist

Similar to other elites of Renaissance Europe, the Tudors had an interest in the artistic legacy of ancient Greece and Rome. The decorative artists of sixteenth-century England, however, often blended this classical tradition with motifs from the natural world. They drew upon both the long- standing conventions of floral symbolism and the untamed wilderness beyond the confines of towns and palaces, experienced through the ritual of the hunt and frequently evoked in contemporary poetry and drama.

The mazes, topiary, and terracing of Tudor gardens provided a controlled experience of nature, while elaborate court masques and choreographed tournaments were make-believe settings for courtiers to evoke chivalric romance and pay tribute to the monarch, particularly Elizabeth I, who encouraged acts of public devotion from her courtiers. Such events reveal a nostalgia for the early Middle Ages, rooted in the (originally Welsh) Tudor family’s appropriation of King Arthur as a legendary ancestor. Interlacing geometric straps evoking Celtic knotwork and Anglo-Saxon manuscripts appear in decorative patterning on everything from armor to table carpets. Combining the classical, the natural, and medieval revivalism, Tudor arts attest to the emergence of a unique English Renaissance aesthetic.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Allegories and Icons

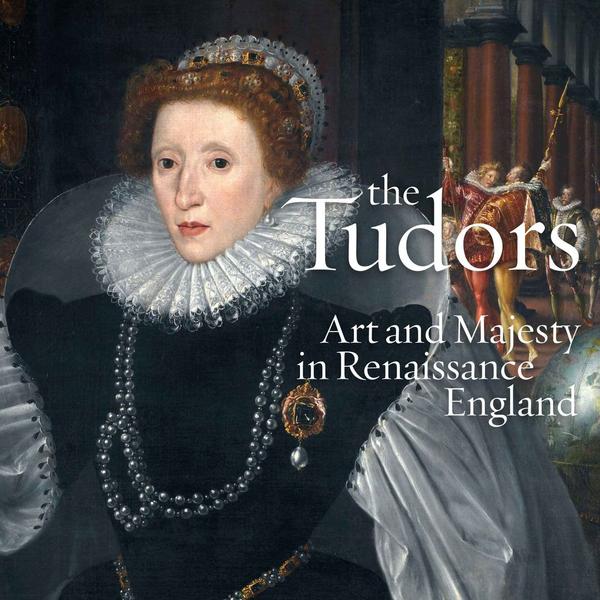

591. Queen Elizabeth I (“The Ditchley Portrait”), Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, ca. 1592

ADAM EAKER:

If visitors think back to that very modest image of Henry VII, a relatively realistic depiction of him as a middle-aged suitor, they’ll see what a dramatic transformation royal portraiture has undergone to now being a grandiose, life-sized depiction of the monarch as a supernatural figure of immense power.

NARRATOR:

Curator Adam Eaker.

ADAM EAKER:

So, we see Elizabeth here at the height of her glory, standing on a map of Southern England; and the sky behind her is bisected into sun and storm. She’s shown as a figure who literally causes the sun to shine. She’s the embodiment of all power. And even her body is really transformed by this strange silhouette that would forever be associated with her, with the incredibly tapered waist, the padded sleeves and then this wide farthingale skirt.

NARRATOR:

The portrait is by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger. It seems to have been planned as a surprise gift to the Queen from one of her courtiers, Sir Henry Lee. The face, showing sunken cheeks and signs of aging, didn’t please Elizabeth. When later copies were made of the portrait, she appears much younger.

Elizabeth was determined to control her public image. This proclamation gives us an insight into her anxiety:

FEMALE VOICE:

Through the natural desire that all sorts of subjects, both noble and mean, have to procure the picture of the Queen’s Majesty, great number of Painters do daily attempt to make portraitures of her Majesty wherein is evidently shewn that hitherto none hath sufficiently expressed the natural representation of her Majesty’s person, favor, or grace…

NARRATOR:

It was all part of the tightrope Elizabeth had to walk as only the second reigning Queen of England.

ADAM EAKER:

And she did so very successfully through the cultivation of this mystique in portraiture that really departs from any conventions of realism.

###

Playlist

The Protestant Reformation brought about the wholesale removal and destruction of religious images in English churches. While some artists experimented with new kinds of religious painting that would inspire intellectual contemplation, most instead focused their attention on investing the monarch, as newly proclaimed head of the church, with sacred authority. During Elizabeth I’s reign, printmakers, many based on the continent, created mass- produced images that celebrated the queen as protector of the Protestant cause.

Painting in the Elizabethan period reveals a stylistic shift away from the naturalistic portraits made under Henry VIII, particularly as embodied in the work of Hans Holbein. Facing enormous pressure as an unmarried woman ruler, Elizabeth exerted tight control over her image. Well into her sixties, she was depicted as an ageless and semidivine beauty. Her carefully vetted portraitists drew upon the elaborate allegories devised by court poets to pay tribute to the queen and her immense powers. Courtiers followed the monarch’s lead, commissioning portraits that reveal less about the sitters’ appearances than about their literary tastes and idiosyncratic personal symbolism. Such paintings delight the eye with their flattened decorative surfaces and close attention to the rendering of textiles and jewels.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.