Engaging experimental cartographies

When it comes to representing vast global regions like Oceania, how might museums acknowledge the complexities of colonial histories, Indigenous knowledges, and seafaring traditions while still orienting visitors to a specific geographic location? And how can museums counterbalance American and European cartographic norms with distinctly Pacific perspectives on space, time, and relation? Maps are more than didactic tools; they actively shape how viewers perceive and imagine the world. In museum settings, maps often serve as an entry point for visitors to orient themselves, yet these representations are rarely neutral.

In seeking alternative approaches, curators of Oceanic art at The Met collaborated with artist, building practitioner, and educator Sean Connelly (Kanaka Hawai‘i / Pacific Islander American / Ilocano) to present an experimental cartography for the newly reinstalled galleries in the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing. Drawing on Connelly’s larger body of work over the past fifteen years—which includes projects and interventions encompassing sculpture, architecture, film, and cartography to center cultural resurgence, food sovereignty, and land justice grounded in Oceanic cosmologies—the artist adapted a 2016 animated map called Spheric Oceania from their ongoing series Africa–Pacific (2014–24). The result offers an alternative cartography that not only repositions visitors geographically but also sparks a more holographic (and holistic) conversation about how people in Oceania interact with and perceive space, time, ocean, land, sky, and life.

Sean Connelly, installation view of Africa-Pacific (2024), Osage Gallery Hong Kong. © Sean Connelly

Resisting colonial conventions: Why we need an alternative

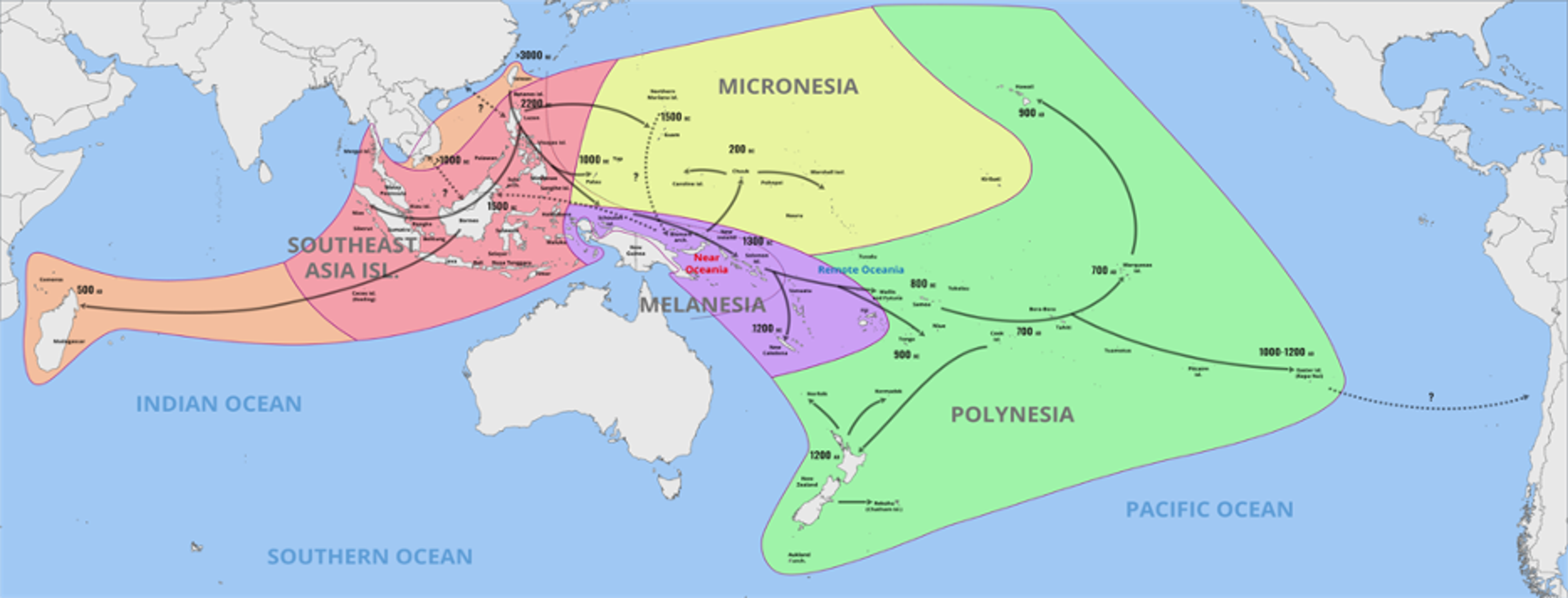

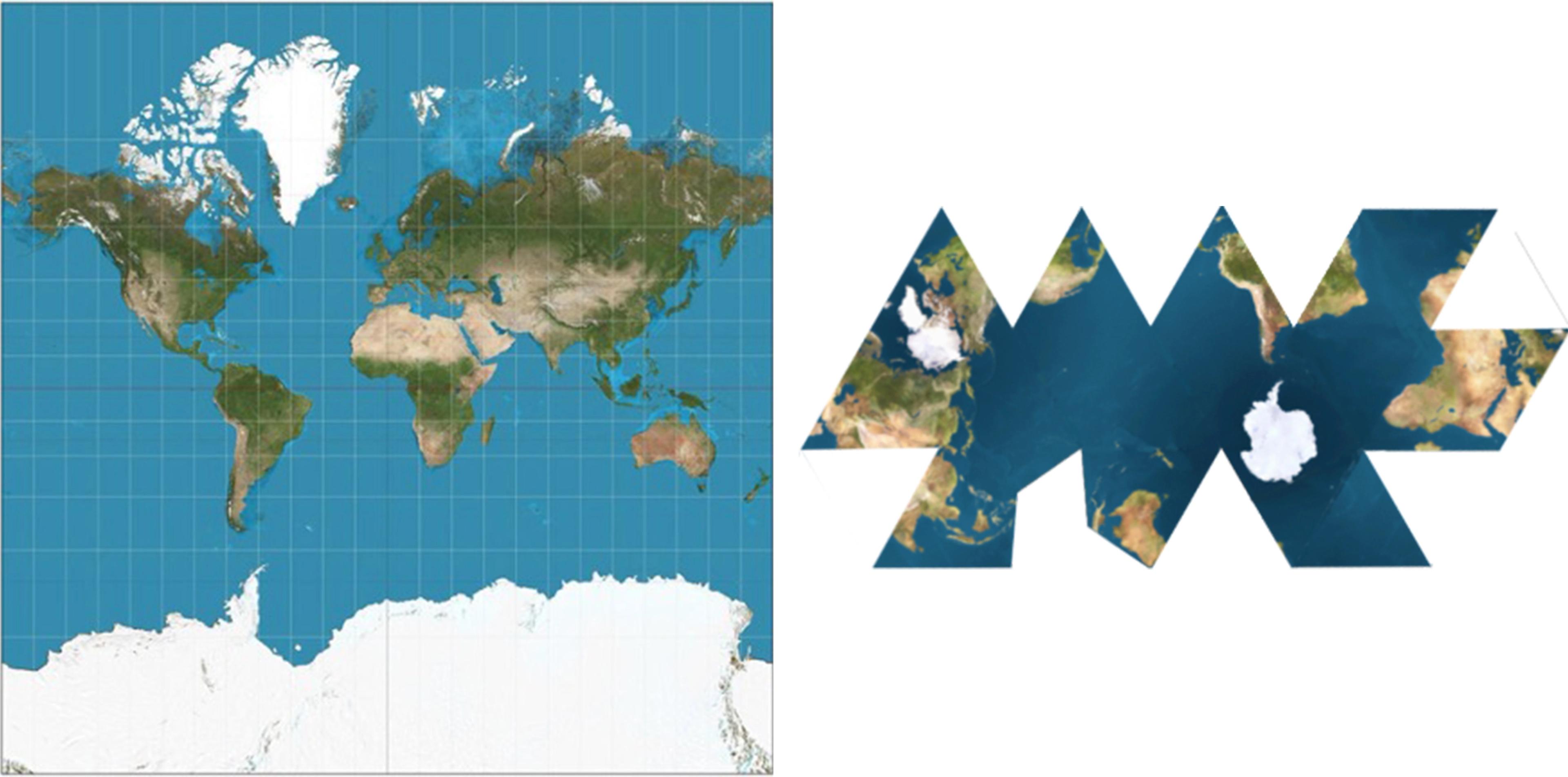

The term “Oceania” encompasses the roughly 20,000 islands in the Pacific Ocean, from coral atolls in the northwest (such as Guam and the Marshall Islands), larger and densely forested islands (such as Papua New Guinea and Aotearoa New Zealand), equatorial archipelagos rich with palm trees (such as Tahiti and the Cook Islands), and even the drier continental island of Australia. Maps of Oceania often divide the region into smaller areas, conventionally known as Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia (a nomenclature proposed by French Admiral Dumont d’Urville in a paper he presented to the Société de Géographie in Paris, 1832). Despite their ubiquity today, these named divisions rarely reflect Indigenous Pacific worldviews. Early European navigators in the eighteenth century—and the Western institutions that inherited their maps in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—viewed the ocean from a fixed, top-down perspective where Europe was central and Oceania was at the margins. Maps like the Mercator projection drastically enlarge higher-latitude regions (Europe, North America) while shrinking Africa, South America, and the Pacific, giving a distorted sense of Oceania’s scale and significance. On the contrary, projections like dymaxion (below) can present the globe cut in ways to show the ocean as continuous.

Connelly believes it is increasingly important to acknowledge how maps have been used as tools for asserting Western peoples’ claims to the space of Oceania, because mapping has historically served imperial ambitions—staking claims, dividing peoples and territories, as a strategy to facilitate capitalist extraction of resources, human and natural alike. This has fed a persistent misconception of Oceania as a remote expanse dotted with “tiny islands.” Two renowned Pacific scholars Albert Wendt and Epeli Hau‘ofa led the charge in insisting on an alternative: rather than “islands in a far sea,” they asserted a reframing of Oceania as a “sea of islands,” emphasizing the dynamic interconnections among its peoples, genealogies, and ecosystems.[1]

Map showing the migration and expansion of the Austronesians. Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

World maps by two different mapping projections: Mercator (left), Dymaxion (right). Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0

Rethinking museum maps

Introductory maps guide visitors through the origins of the objects on display in the galleries for Oceanic art in the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing. The maps offer geographic coordinates to help orient visitors to the many distinct regional and cultural groups whose art is on display. Oceania is of course a conceptual idea, a construct designed to impose order on a vast, interconnected region that spans the Pacific and Indian Oceans and makes up one third of the globe. Mapping Oceania presents a unique cartographic challenge: on a large-scale map, many islands are too small to be accurately drawn, making the ocean appear empty, when indeed it is not. Integrating maps into the new Oceania galleries therefore required a careful and critical approach to cartographic representation, one that acknowledges the complex histories and ongoing, expansive relationships that define the region.

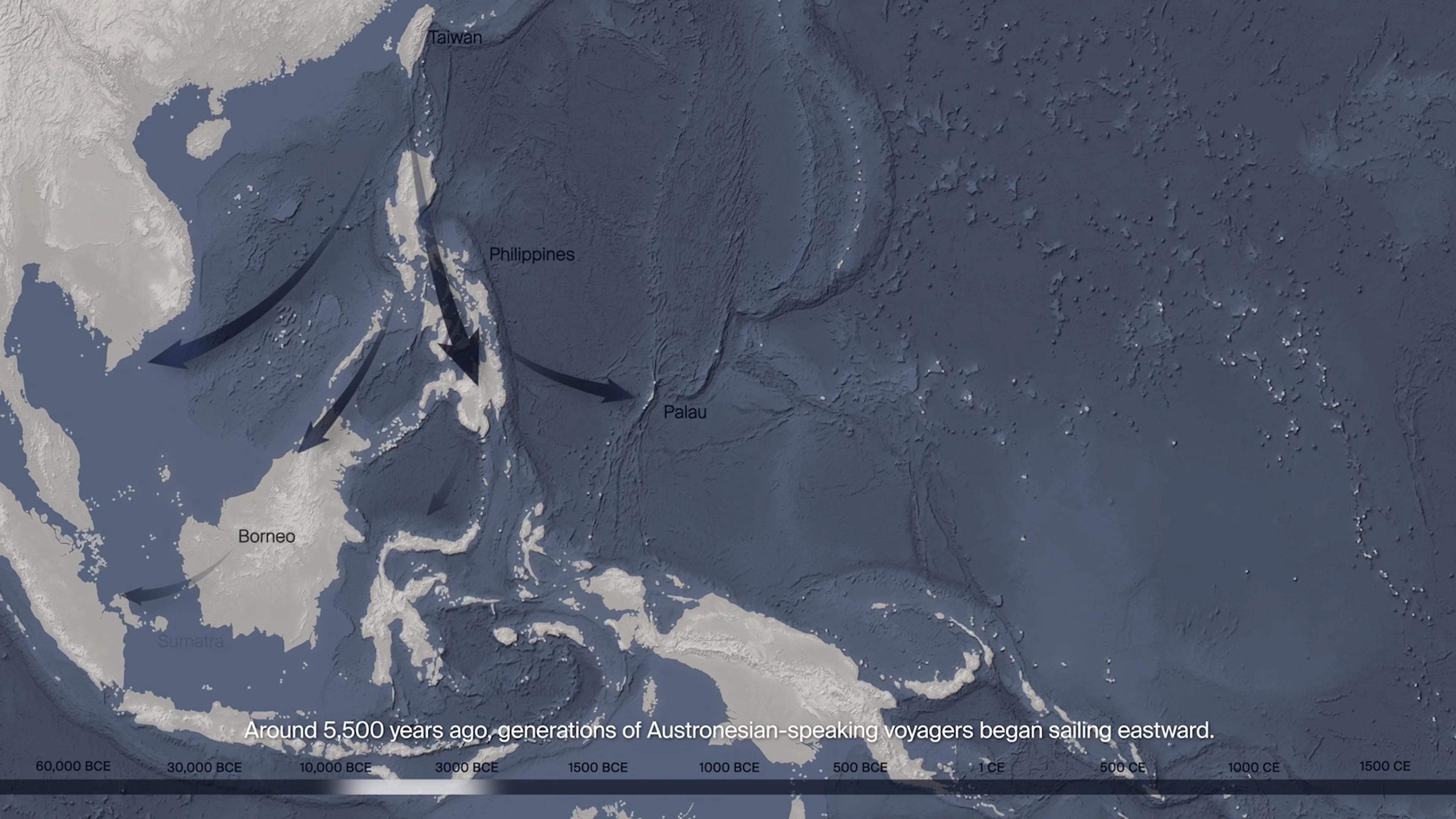

Still of animated map in the new Oceania galleries at The Met, showing Austronesian migration into Southeast Asia and the Northwest Pacific.

The large, animated map that greets visitors at the principal entrance to the Oceania galleries shows the early generations of Papuan-speakers who walked across land bridges to settle in Australia and Highlands New Guinea when this landmass (Sahul) was connected to the continental shelf of mainland Southeast Asia (Sunda). This migration was followed some 35,000 years later by transoceanic canoe voyages with many waves of seafaring expeditions by Austronesian-speakers who moved south and eastward into the vast expanse of open sea that came to be known as the Pacific Ocean. Given their shared linguistic roots, the descendants of this second phase of migration are often referred to as Austronesians. (It is this Austronesian story that is the focus of Connelly’s Spheric Oceania.) Predating the use of written maps, the Indigenous seafarers of the Pacific did not engage oceanic space from the perspective of a two-dimensional vantage. Instead, as esteemed navigators like Mau Piailug (Marshall Islands) have recovered in contemporary times[2], the oceanic relationship with the seascape is embodied and based on observed connections between the human and the canoe. The stars provide a different kind of map, as do the ocean currents, swells, water temperature, and wind patterns—all interpreted in relation to the position of the canoe itself.

For Indigenous navigators of Oceania who have inhabited the region for tens of thousands of years, the cartographic process is bound to unique spatial relationships that are lost in conventional Western maps of the region. The space around them rested upon a keen understanding of the arcing sky overhead (essentially a dome created by the horizon line), and the inferred continuity of the other half of that sphere underneath the surface of the water. The canoe locates itself in the center of this sphere, rather than in relation to land. One cosmogony of Austronesian origin that affirms this spherical perspective suggests the earth is a primordial calabash (gourd), whose seeds were scattered into the sky to become stars.[3] In Spheric Oceania, Connelly similarly envisions the planet’s dome when mapping the Pacific, though the use of the sphere is not directly referring to this specific story, which is just one of a wide array of creation accounts across the region.

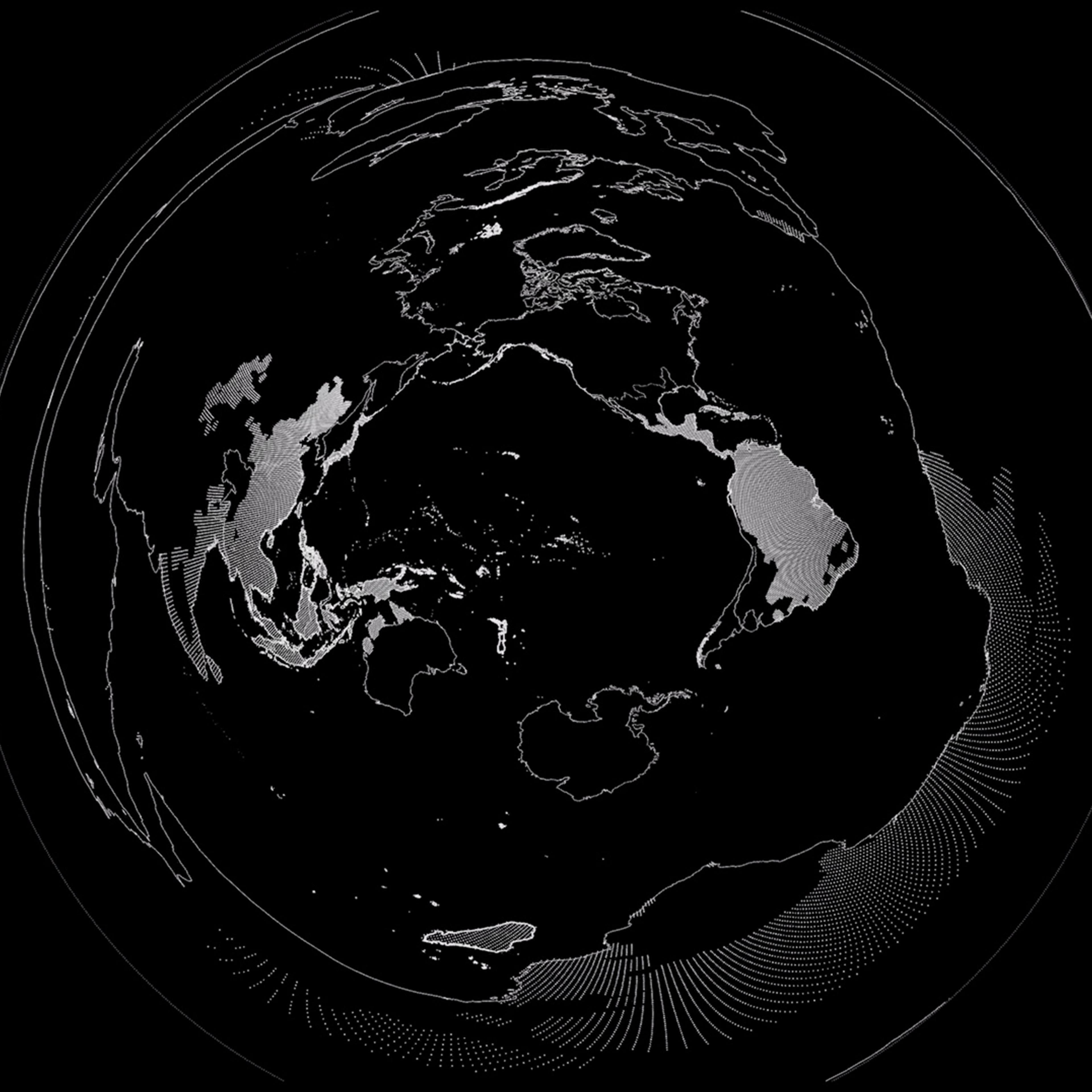

Sean Connelly, still from Spheric Oceania (2016) showing Earth as a hemisphere. © Sean Connelly

Sean Connelly’s Spheric Oceania: An overview

Connelly’s work spans sculpture, architecture, film, and cartography, but across all forms he builds a coherent practice that centers Oceanic cosmologies, land justice, and cultural resurgence. In the original digital piece Spheric Oceania (2016) which has been adapted for The Met gallery map, Connelly combines cartographic tools (such as GIS) with architectural modeling to reframe oral histories of canoe navigation, linguistic data, and the global distribution of Austronesian “canoe plants” (e.g., taro and sweet potato) that were carried on board the early eastward voyages and remain highly valued nutritional resources in Hawai‘i and the Pacific Islands today. The resulting work stitches this wealth of data together, reorienting viewers to see and understand Oceania not as a flat expanse, but as a rich hemisphere of interconnected sources—land, sea, and sky joined in one productive continuum of place and life. Connelly’s practice, which he often frames as a form of Indigenous architectural cartography, positions him at the forefront of contemporary Pacific art and design, where questions of sovereignty, space, and futurity converge.

Key strategies in Spheric Oceania

Connelly employed at least four principal visual strategies in the animation to assist this curatorial reimagining of Oceanic space and cartographies for the benefit of viewers visiting the Museum's Oceania galleries. This visible index of dots, lines, and shading are derived from Connelly’s research and the analysis of data points that find representation in a system of visible marks layered onto digital mappings.

1. Reorienting the sphere

Instead of fixating on a flat orientation with north at the top, Spheric Oceania begins with an image of Earth as a rotating hemisphere, suggesting the ocean and sky form a single expanse. This inversion subverts the expectation that the “top” of a map must be the Northern Hemisphere. By situating the ocean as a cosmic container, Spheric Oceania invites viewers to contemplate Oceania not merely as an extreme environment divided between continent and ocean, but as a vessel where land, sky, and sea converge and continuously shape each other and the cultures who inhabit it.

2. Bounding boxes: Visualizing navigational zones

Next, the animation slowly reveals the bathymetric contours beneath the ocean’s surface, hinting at the crucial depth and topography that Indigenous seafarers have always considered in reading the patterns of waves and swells that characterize the ocean and direct its velocity. Connelly then applies shapes he describes as “bounding boxes” around each island, terms derived from references in the oral accounts of Pwo (master) navigators in Micronesia who describe the approach to islands perceived through zones of possibility (rather like a cone of vision that expands as you draw nearer).

Sean Connelly, still from Spheric Oceania (2016) showing “bounding boxes” used to conceive the extent of perceiving the presence of islands. © Sean Connelly

Rather than aiming for a specific landing point on an island, navigators read subtle signals—wave patterns, cloud formation, bird flight—to locate an island’s presence. Connelly translates this into GIS geometry: a 200-mile buffer (the distance at which the presence of an island may become noticeable) and a 30-mile ring (representing a concept of observations such as a typical extent of a bird’s daily flight patterns to and from an island in search of food). Visually, these dashed boxes remind us that islands are not just static coordinates but living centers of knowledge.

3. More than triangles: Reclaiming planetary ancestral connection

Solid lines link Hawai‘i, Rapa Nui, and Aotearoa together, forming what is commonly referred to as the “Polynesian Triangle.” However, Spheric Oceania moves beyond this trope by adding real data from the groundbreaking voyages of the double-hulled Hawaiian canoe named Hōkūleʻa—launched in 1975 by the Polynesian Voyaging Society (PVS) and widely acknowledged as a milestone in the recovery of navigational knowledge that has led to the revival of customary wayfaring throughout the Pacific. These crisscrossing routes reveal a complex network rather than a triangle, tracing the paths the PVS made against winds and currents and underscoring the sophisticated knowledge required to traverse immense oceanic distances. These voyaging lines represent genealogical channels reaching back millennia. Connelly highlights how modern-day voyages revive ancestral skills, illustrating that Indigenous seafaring is an ongoing narrative of cultural resurgence rather than a relic of the past.

Sean Connelly, still from Spheric Oceania (2016) showing the navigational highways used by Austronesian voyagers and the “grow regions” where canoe plants are distributed. © Sean Connelly

4. Language families and canoe plants

Finally, Spheric Oceania expands its scope to underscore the breadth of Austronesian peoples in both language, food, resources, and material culture. Layered linguistic data marks the Austronesian relationships that exist with Taiwan, the Philippines, and Madagascar. This layer also overlays canoe plant distributions like the ʻuala (Hawaiian for sweet potato), introduced by Pacific Islanders into Polynesia from South America long before European contact.[4]

By shading “grow regions” across Africa, Asia, and the Americas where ʻuala and taro (called kalo in Hawaiian) can thrive, Connelly reveals how staple plants themselves trace centuries-old voyages and exchanges that were both transoceanic and transcontinental. While these dotted regions are minimally represented on the continent of Australia, the rich darkness across the rest of the land outlined in the map sets this area apart, acknowledging its distinct linguistic and cultural lineages resulting from the Papuan-speaking migration that occurred long before the Austronesian voyages of 3,500–5,000 years ago.

Meanwhile, Madagascar enters the frame at the left, reflecting the well-documented linguistic connections that underscore the extensive roots that link the network of Austronesian-speaking peoples well beyond the Pacific Basin. Even speculative connections to places as distant as Scandinavia invite viewers to imagine just how far these seafaring routes might have extended. In fact, Hawaiian oral traditions recount stories of interaction with people from lands toward the North, reminding us that these connections are more than just speculative. Each discretely dotted region represents a dynamic, living archive, one that carries the voices of navigators and cultivators who have long shaped the spatial environments of Oceania.

Sean Connelly, still from Spheric Oceania (2016) showing the farthest possible reaches of Austronesian expansion. © Sean Connelly

Why these visual interventions matter

Within the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, Connelly’s Spheric Oceania acts as an essential counteraction to Western mapping conventions. Rather than relegating the ocean to the margins (as commonly seen in a Mercator projection, for instance) or depicting the Pacific as a flat, empty space, Connelly’s animation places the ocean and all of its inhabitants (canoes, stars, people, fish, birds, seaweed, and plants) at the center of a multidimensional story that is constantly moving and evolving. This is, in essence, a decolonial gesture: it shifts authority from imperial cartographic assumptions (that seek to control or fix) to a more open and fluid system in which the Indigenous knowledges that have shaped Oceania for tens of thousands of years can find expression and continue to flourish.

For museumgoers who may be unfamiliar with Pacific histories, the animated spheres, bounding boxes, and genealogical lines prompt a deeper curiosity about how artworks in the galleries may relate to each other across time and space. Visitors are encouraged to see Oceania as a dynamic realm of overlapping cultures, shared genealogies, and continuous exchange. Spheric Oceania embodies a paradigm shift in how we can think about and visualize the Pacific in ways that align with Indigenous Oceanic relationships with the lands and seas from which its peoples descend. As museums worldwide reconsider how they represent Indigenous and global communities, Spheric Oceania offers a compelling model of what a more inclusive, imaginative cartography might look like. Rather than fixating on borders or flattening entire worlds into the margins of chronological timelines, we can choose to center relationships, genealogies, and oceanic flows, thus honoring the living cultures whose histories continue to shape our collective global story across generations.

Watch Spheric Oceania (3 minutes).

Notes

[1] Epeli Hauʻofa, “Our Sea of Islands,” in We Are the Ocean (University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2008), 27–40; Albert Wendt, “Towards A New Oceania,” Mana Review 1 (1976): 49–60.

[2] Imogen Lepere, “Pius ‘Mau’ Piailug: Master Navigator of Micronesia,” JSTOR Daily, August 21 ,2023, https://daily.jstor.org/pius-mau-piailug-master-navigator-of-micronesia/.

[3] Nathaniel Bright Emerson, note 15 in David Malo, Hawaiian Antiquities (Moolelo Hawaii) (Hawaiian Gazette Co. Ltd., 1903), 125.

[4] Caroline Roullier, Laure Benoit, Doyle B. McKey, and Vincent Lebot, “Historical collections reveal patterns of diffusion of sweet potato in Oceania obscured by modern plant movements and recombination,” PNAS 110, no. 6 (2013): 2205–10, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1211049110.