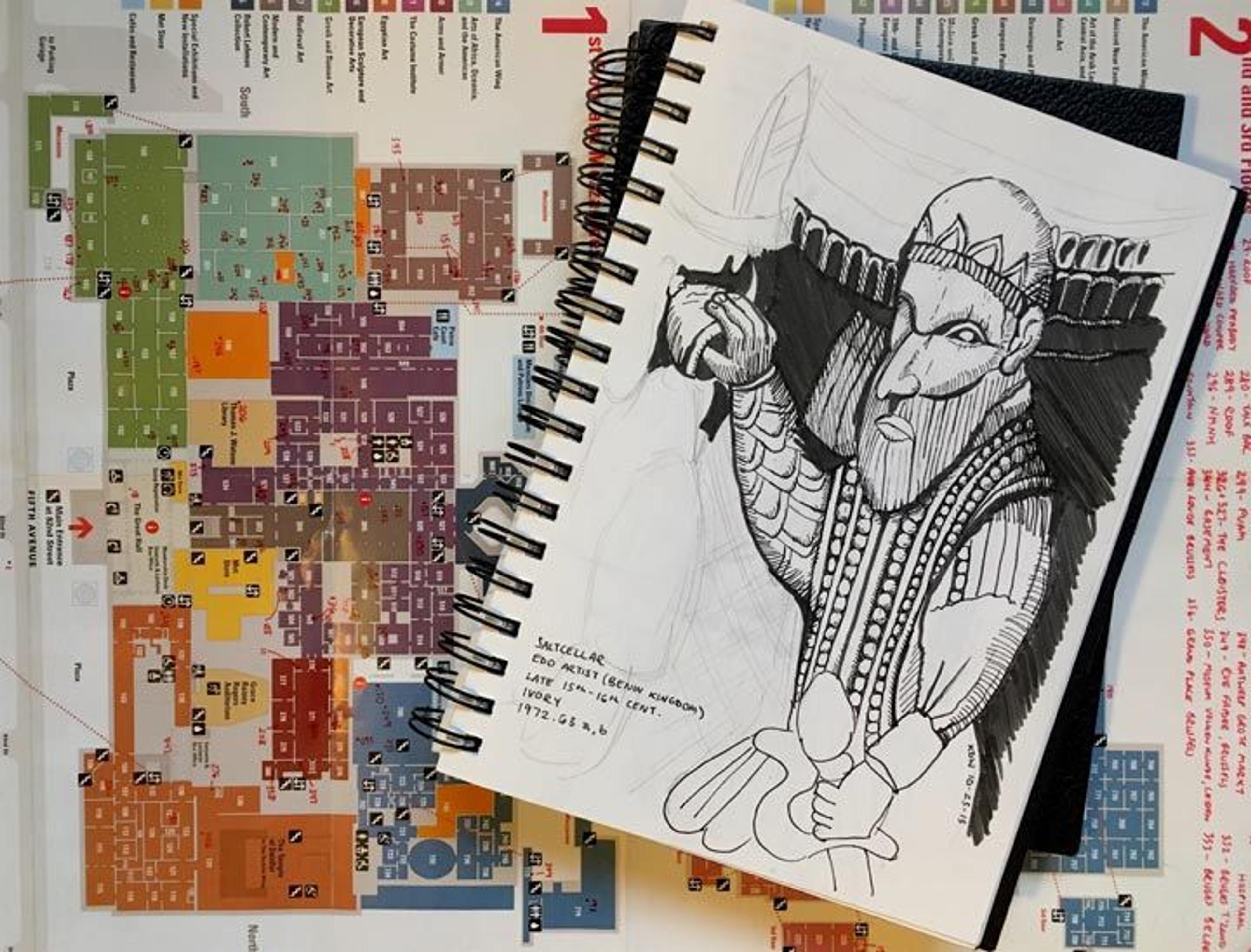

Metropolitan Sketchbook #55, with a gallery map marking the location of each day's drawing. All photos courtesy of the author except where otherwise noted.

«During my yearlong fellowship at The Met in 2015–16, I kept a daily sketchbook, marking each day by drawing a work of art. Some drawings took hours, others just minutes. Together, the sketches make up a record of my year. »

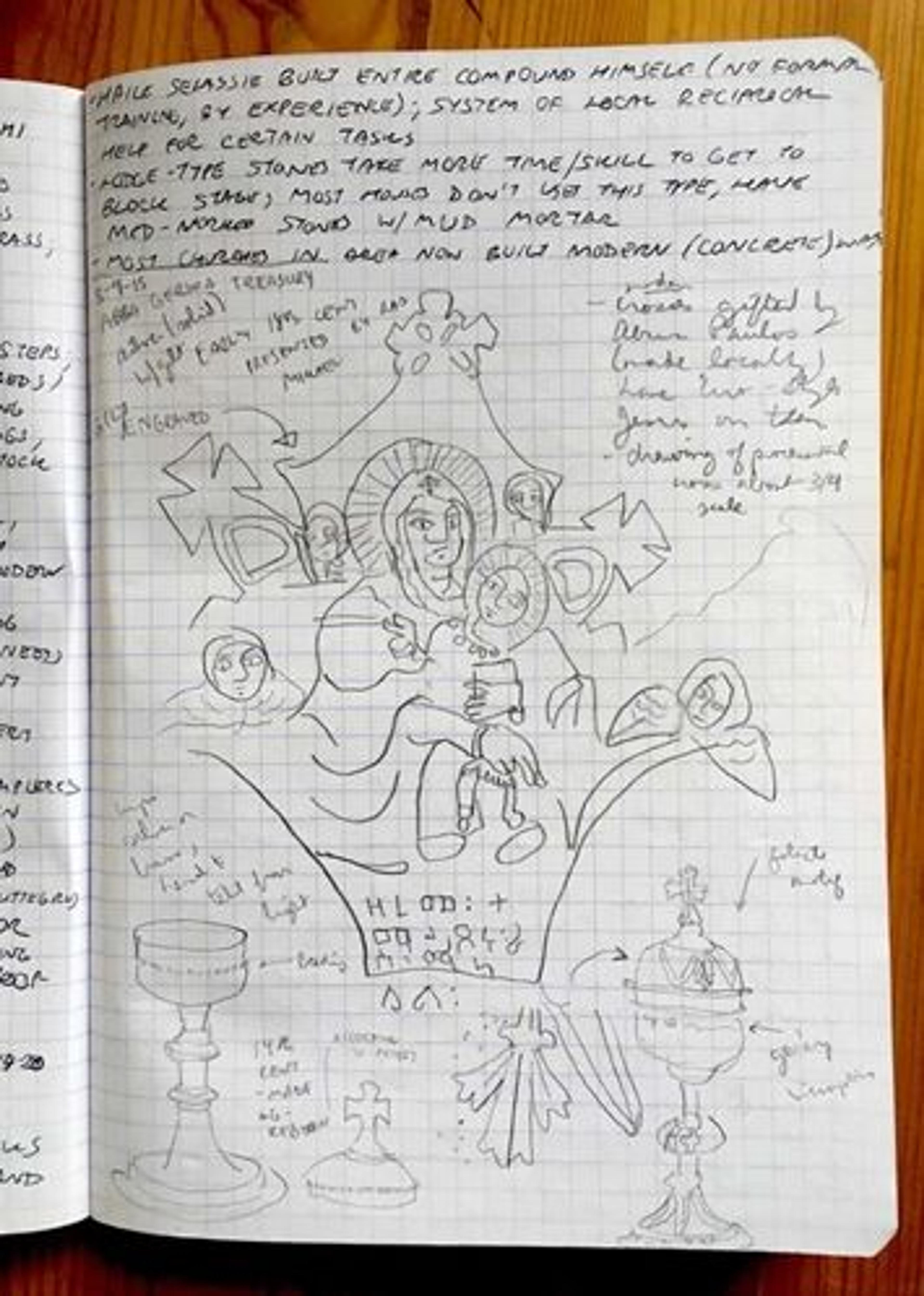

The idea for the project came to me after returning from a research trip in Ethiopia. At the monastery Enda Abba Garima—home to some of Christianity's oldest illuminated manuscripts—the monks welcomed me into the church treasury, but did not permit photographs. The site was crucial to my research, so in a last-ditch effort, I asked if I could sketch. Given the go ahead, I drew by flashlight in the dark room, with the monks looking curiously over my shoulder.

Right: The author's field notebook from the summer of 2015, opened to sketches drawn at Enda Abba Garima, an Ethiopian monastery

Although I had always made art, it had been a while since I had drawn; my skills were rusty, and I struggled to capture everything in the short time I had with these holy objects. After years focused on archives and books, I realized that my ability to see—the most basic skill of an art historian—now needed work. And where better to practice seeing—and learning how to look—than at The Met?

Creating a daily sketchbook—one object for each day of my fellowship—was a way to build my skill, develop my eye, and take advantage of the fact that I would call The Met my home and office for the next 366 days.

Screenshot of the "Metropolitan Sketchbook" project on Instagram

Each sketch in the project that I dubbed my "Metropolitan Sketchbook" offered a short break in a long day filled with curatorial projects and the daunting task of completing my doctoral dissertation. Sometimes I picked a work at random, walking until something caught my eye. On other days, I asked for suggestions, or used the sketch as a reason to visit a new exhibition. Current events, pop culture, and even holidays prompted some sketches, occasionally launching a thematic series or "mini-exhibition" on topics such as love, feasting, or the depiction of Christ across cultures. Others, like that of a golden Akan staff, used the act of close looking to initiate a research project.

A post shared by Kristen Windmuller-Luna (@kwindmullerluna) on May 9, 2016 at 1:25pm PDT

Day 252. A sculpture of a falling gladiator in the Charles Engelhard Court. #lifeimitatesart

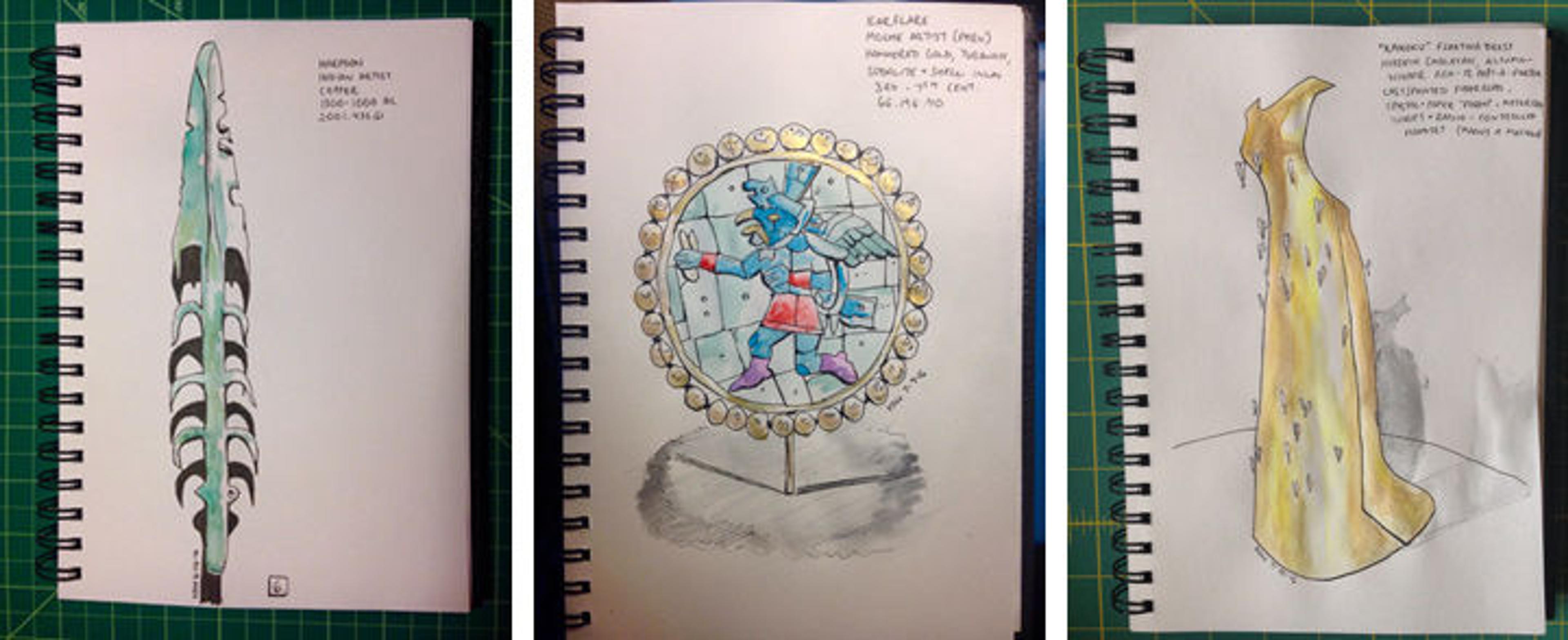

Often the sketchbook was personal, with the day's object reflecting events in my life, documenting travel, responding to a gallery talk, or serving as a diary for musings on dissertation progress and life at The Met. A bronze sculpture of a falling gladiator captured the way I felt after hours spent formatting dissertation footnotes. Comments and hashtags posted along with my sketches on Instagram served as virtual gallery labels, adding facts, reflecting my perspective on art and curating, or sometimes making a corny art history joke. Weekends were for longer sketches, or for media too messy for the galleries, like ink, watercolor, pastel, or charcoal.

Three watercolor and ink drawings, representing a copper harpoon from India, a hammered gold earflare with messenger from Peru, and a "Kaikoku" floating dress from Britain.

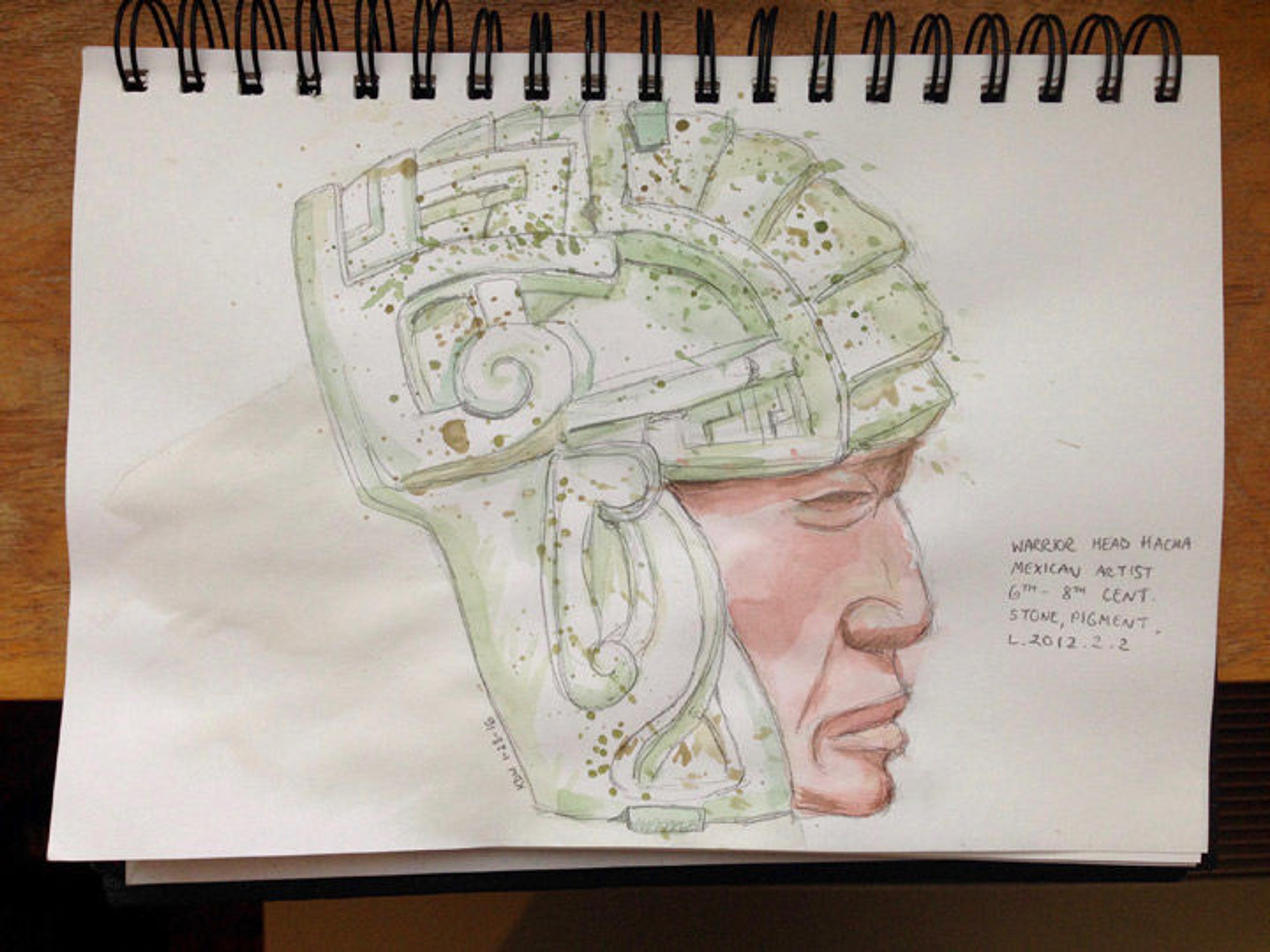

"Metropolitan Sketchbook" was also about representation, inclusiveness, and making connections. Like many students of the last decade, Western art dominated my art history classes and texts. In contrast, I wanted this project to reflect the diversity of The Met's collection and of human creativity, whether it originated in Mexico or Mozambique.

Day 145. A hacha worn by a ballgame player, carved in the shape of a ballgame player. Veracruz artist, Mexico. On loan to The Met. #meta

Every work in the sketchbook is attributed to an artist, even if their name has gone unrecorded, recasting what might be merely "Roman" or "Senufo" on a gallery label as "Roman artist" or "Senufo artist" to acknowledge the human maker of that piece of art.

A post shared by Kristen Windmuller-Luna (@kwindmullerluna) on Feb 21, 2016 at 1:10pm PST

Day 174. Oracle Figure (Kafigeledjo), Senufo artist

And although the sketchbook showcases canonical works familiar to art lovers and students—like Degas's dancers or the Elgin marbles—I've also included artists who should be in the canon but have arguably been neglected because of their gender or ethnicity, like Japanese-American modernist Yasuo Kuniyoshi.

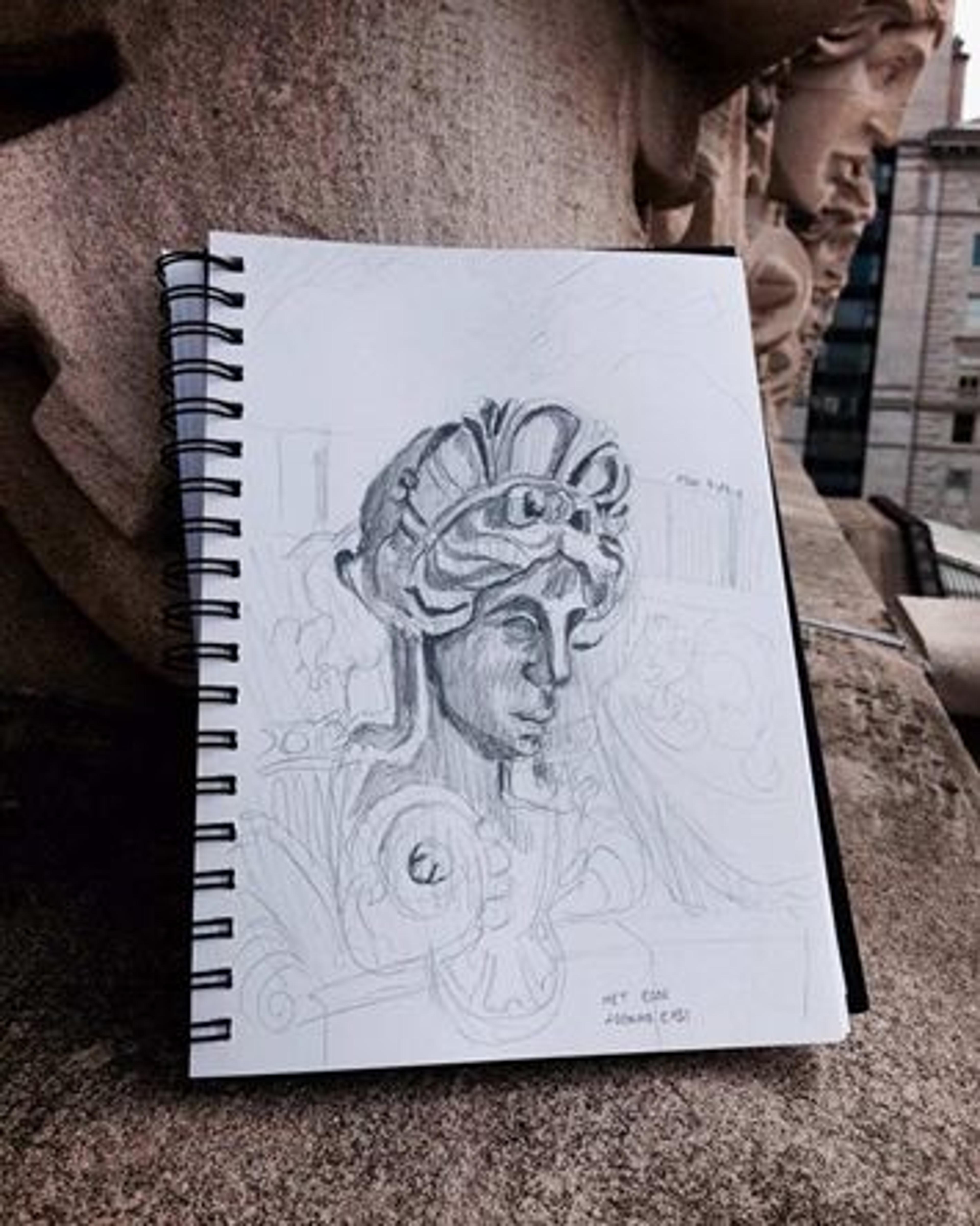

Left: Day 29. Sculptures on the roof

I drew every day. Even on days when I felt tired, or overwhelmed, or just bored with it, I drew. I drew on days when it felt meditative, or even exhilarating. I drew when I was traveling, and even bolted out of bed more than once to make sure I'd gotten the day's sketch in.

The daily practice was technically rewarding—my skills and speed increased. More importantly, getting up from my computer, walking through the galleries, and pulling out my pencils gave me time to clear my mind, stop, and refresh. Sketching every day granted me a renewed ability to "look" and made me appreciate the value of slowing down, absorbing the surroundings, and reflecting on what's important. One unanticipated benefit of the daily sketch was the conversations I had in the galleries: sometimes one-off chats with visitors or guards, but also with unexpected new friends and sketching buddies. In a year where I was largely installed in front of a computer in my cozy office, heading into the galleries each day made my world larger by focusing in.

Sketching was also an incredible way to get to know the Museum. (Did you know you can walk a perfect loop through every department on the second floor? Or get to a secret roof?) I have a special relationship with every piece in my sketchbook. In an image-saturated world, where screens reduce everything to the same size, it's a privilege to spend time up close with the real thing.

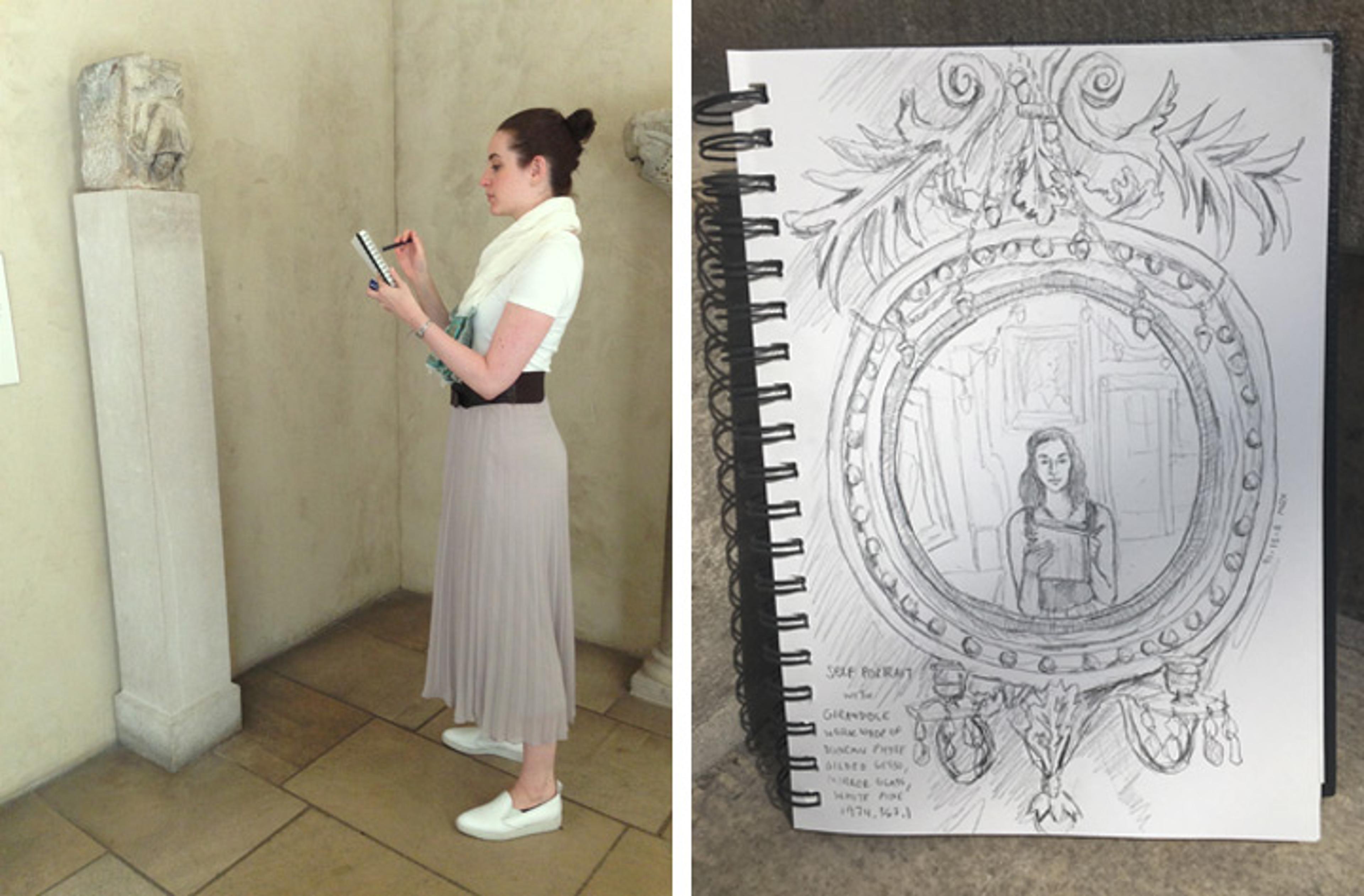

Left: Day 326. Sketching at The Met Cloisters. Photo by Kate Holohan. Right: Day 366. Self-portrait with girandole

After a year of what had seemed like limitless blank pages, suddenly I was down to the last week of my fellowship—and then, down to the last day. My final drawing was a self-portrait, the first one I'd drawn since college. Reflected in a curved mirror, I sketched and took in the sounds of the early-morning Met one last time: quiet punctuated by high heels crossing marble tiles (tap tap); two guards' friendly exchange of chicken recipes ("keep the skin on"); and the swelling soundtrack of Copland's Appalachian Spring drifting from a neighboring gallery.

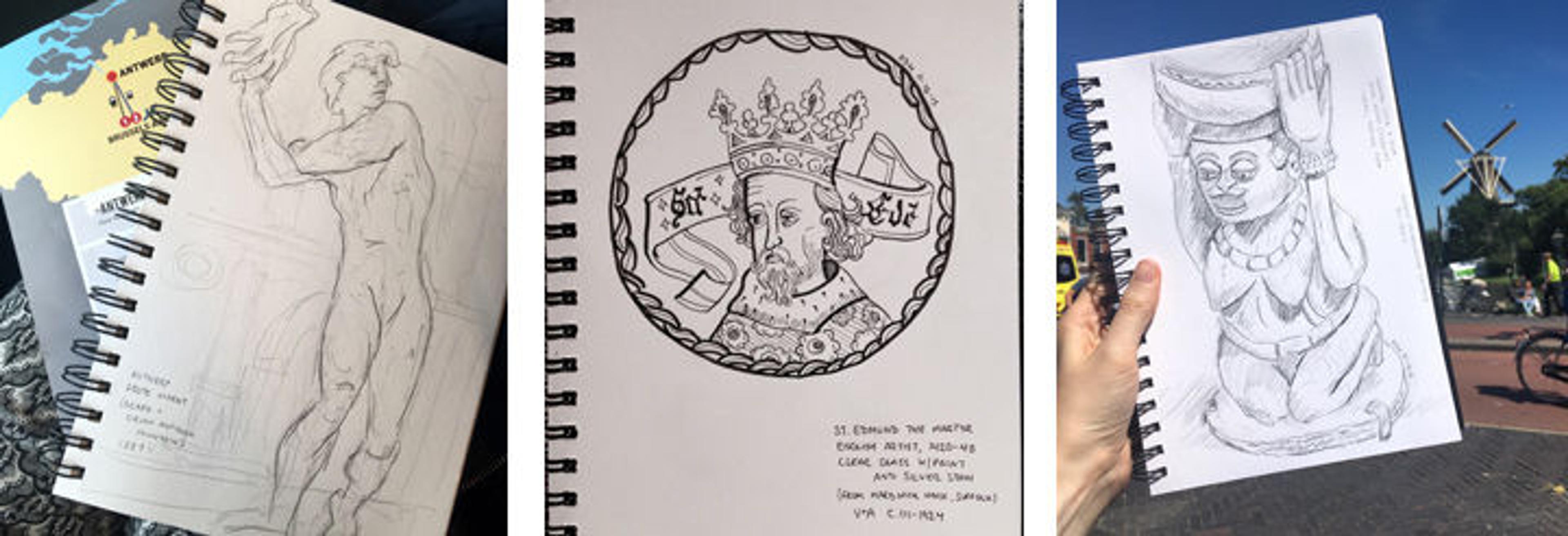

Sketches drawn in Belgium, England, and the Netherlands. #ontheroad

Four-and-a-half sketchbooks later, I had drawn in five countries (US, England, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands), four states (New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey) and Washington, D.C., and some two dozen collections, ranging from my home base at The Met to the once-in-a-lifetime experience of Windsor Castle. In the end, those 366 drawings were a record of my year, the ups and downs of finishing a dissertation, and all the wonderful things that I experienced as a Met Fellow.