In January 1988, artists devoted to AIDS activism formed the Gran Fury collective as the “unofficial propaganda ministry and guerilla [sic] graphic designers” of ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power.[1] Taking their name from the Plymouth car model of choice for the NYPD, Gran Fury members began producing agitprop art with the overarching goal of actualizing a better world for queer people and people with AIDS. Most of the collective’s campaigns were exhibited beyond traditional art spaces through flyers, billboards, and posters. Aimed at the “[hu]man on the street rather than the art world,” their output often recycled images and texts to reach wider audiences.[2] Any profits generated from their campaigns went back into ACT UP and sponsored further art projects.

ACT UP was founded in March 1987 by Larry Kramer, Didier Lestrade, and Vito Russo at the LGBT Center on 13th Street. Still active with numerous international chapters, the organization sought to publicize the AIDS crisis, get AIDS-combatting and life-saving drugs into bodies, and end the crisis. The organization framed AIDS as a political problem, not just a medical one, and brought about a staggering shift in the American history of medicine as well as in public opinion, while lobbying the federal government to expand its budget for AIDS research.

Logo for ACT UP. Image courtesy of ACT UP

This framing (and tactic) was important for many reasons. It emphasized that the virus had far-reaching, costly implications. It also sought to hold government health agencies, elected officials, and insurance and pharmaceutical companies responsible for responding to the needs of HIV/AIDS-affected communities, calling attention to the great American tradition of making business out of healthcare. “Early AIDS advocacy, embodied by Gran Fury and ACT UP, made visible very real data, making the case that there was an active government policy (or lack thereof) to deliberately ignore or silence the dangers and devastation of HIV/AIDS”.[3]

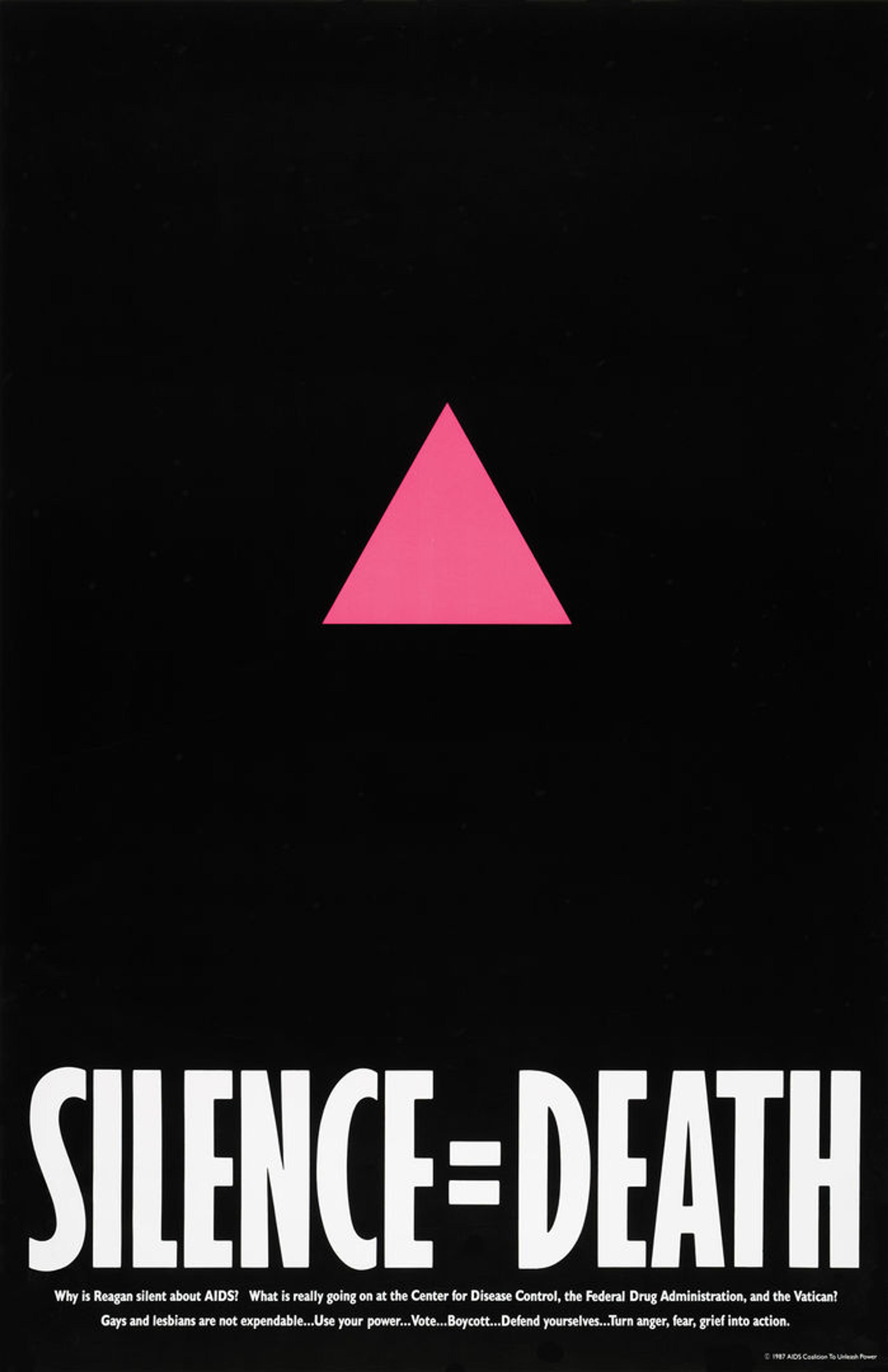

In December 1987, Bill Olander, a New Museum curator (who succumbed to AIDS in 1989, aged thirty-eight), presented the museum’s Broadway window to ACT UP as part of the “Let the Record Show…” installation to demonstrate that some artists chose not to be silent regarding AIDS. While the well-known and oft-recycled SILENCE = DEATH neon sign included in this window display originated with the Silence = Death Collective, which predated Gran Fury, the New Museum installation prompted some of the participating ACT UP members to form Gran Fury as an ad hoc committee. While any ACT UP member was welcome to join, the core group was Richard Elovich, Avram Finkelstein, Amy Heard, Tom Kalin, John Lindell, Loring McAlpin, Marlene McCarty, Donald Moffett, Michael Nesline, Mark Simpson, and Robert Vazquez-Pacheco. The collective was overwhelmingly white and largely, though not exclusively, male.

ACT UP (American, founded 1987). Silence = Death, 1987. Image courtesy of the Avram Finkelstein Archive

Gran Fury’s work appeared in news coverage of the crisis, at protest marches, actions, and zaps, and became a conduit by which ideas originating in ACT UP extended throughout popular culture and the world. Zaps were specific-target-tactics developed by ACT UP to communicate anger and dissatisfaction with institutional indifference to the AIDS crisis, designed to address AIDS issues needing immediate action. Zapping techniques included sending letters, invading offices, picketing, and making “outraged” phone calls. To quote ACT UP: “The more zappers who zap the zappee, the better the zap.”[4]

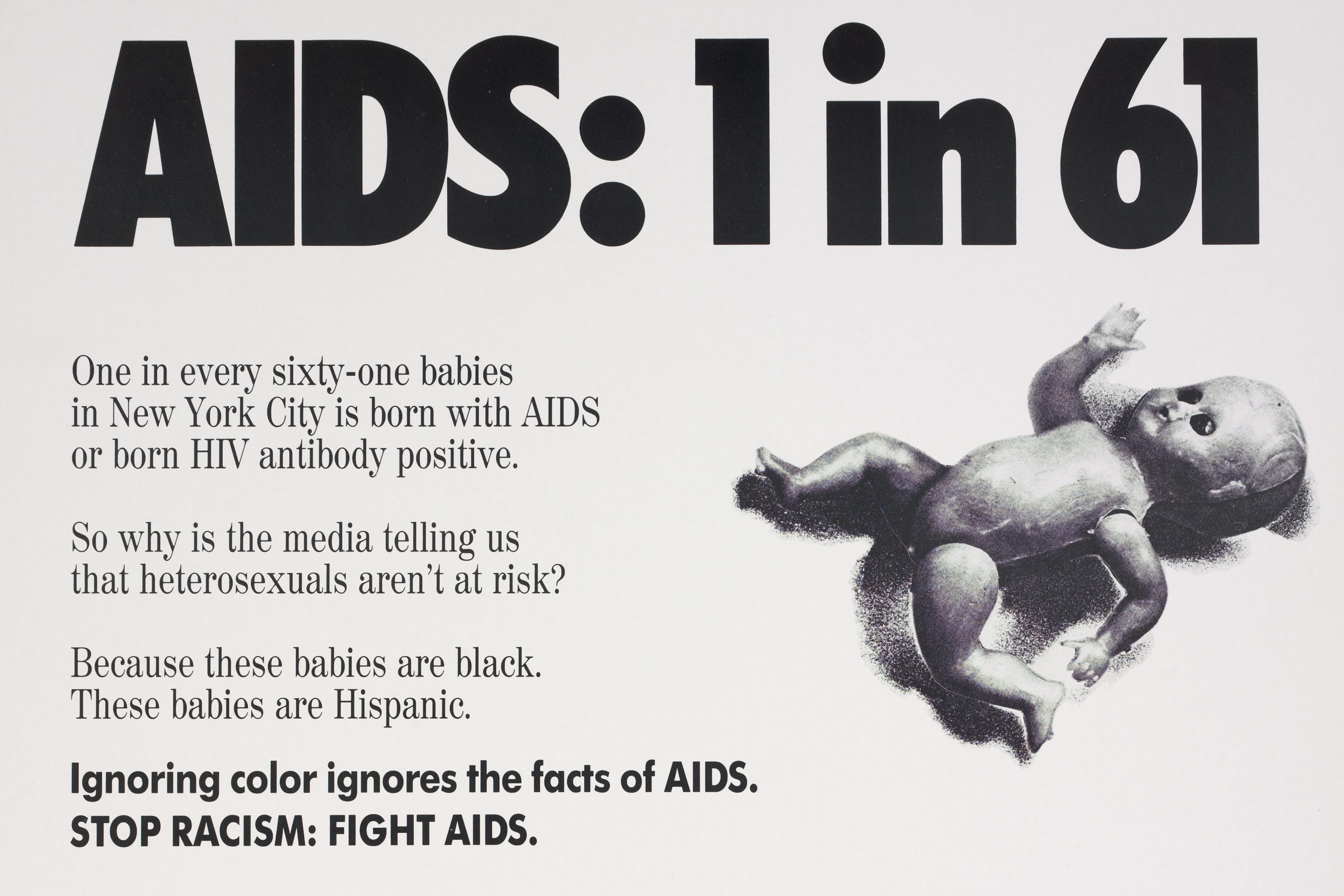

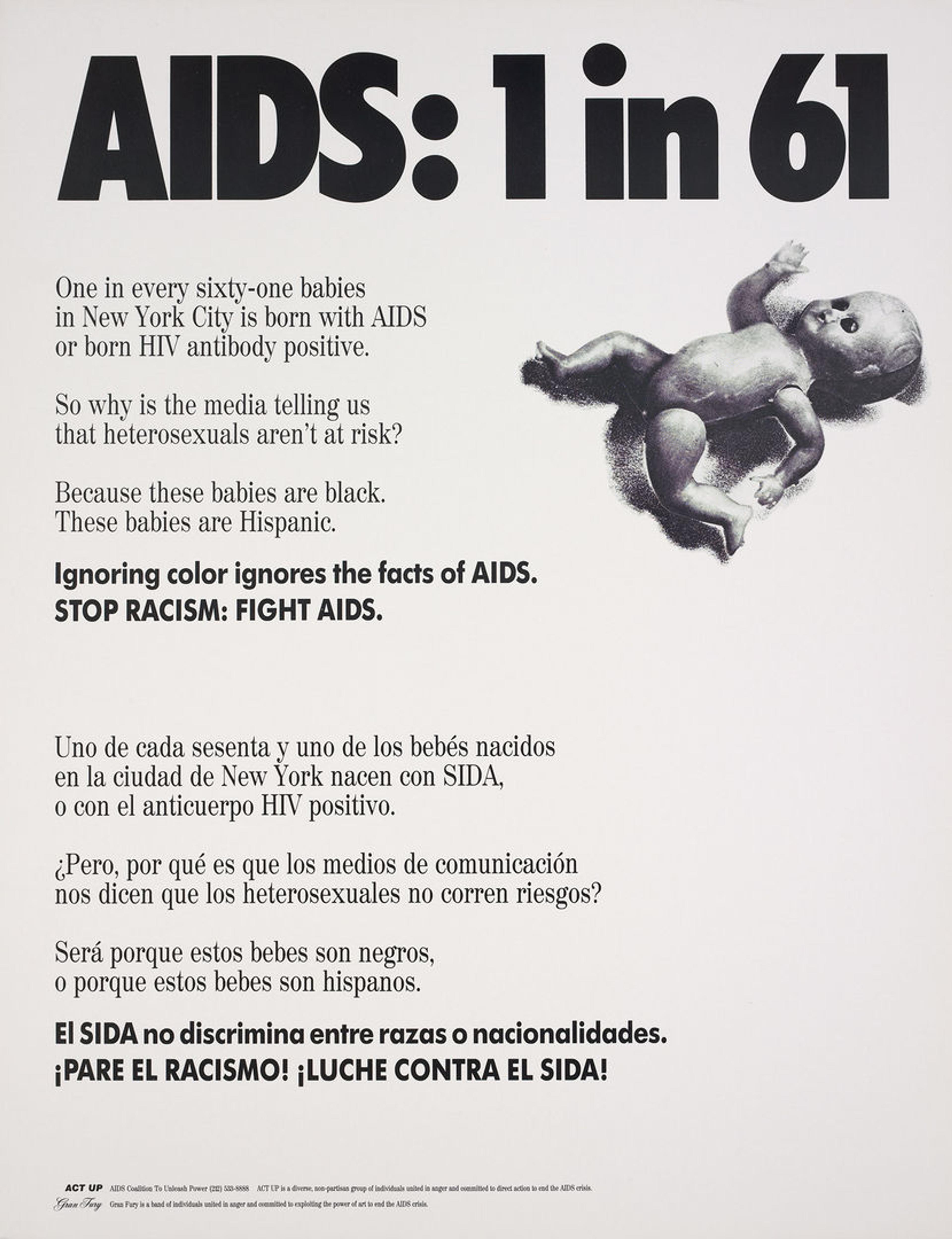

One of the collective’s posters in The Met collection is called AIDS: 1 in 61 (1988). According to members of Gran Fury, this poster came out of the first official meeting of the collective, following the New Museum window display.[5] It is an offset lithograph, of an unnumbered edition, in black on white ground. Offset printing is a common technique for mass producing items such as newspapers, posters, and flyers. As a relatively accessible, affordable medium that often requires more than one set of hands, printmaking such as this lends itself well to artmaking in the collective sense and has been popular among many other movement organizers. For example, the process was used in the likes of Rumbo Gráfico, the newspaper of the Union of Industrial Workers of Graphic Arts, published by Taller de Gráfica Popular in Mexico City; the prints of the Victory Garden Collective; the works of the German revolutionary group SPUR; and posters printed at the Center for Book Arts to be distributed to protesters.

The AIDS: 1 in 61 poster was a test run for Gran Fury, produced in the first weeks of 1988. It was likely intended to accompany ACT UP’s protest outside the offices of Cosmopolitan magazine after the publication ran an article downplaying the risk of heterosexual HIV transmission.[6] The poster sought to alert the public to the shockingly large percentage of children who were contracting the virus at birth as well as to emphasize the racialization of the disease, which disproportionately afflicted Black and Latinx New Yorkers.

Gran Fury (American, active 1988–1995). AIDS: 1 in 61, 1988. Offset Lithograph, 22 x 17 in. (55.9 x 43.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Stanley Posthorn Gift, 2018 (2018.224). Image courtesy of the Avram Finkelstein Archive

While the image features some of the group’s hallmark graphics and came to define Gran Fury, members of the collective consider this to be one of their worst posters, even a failure. Its text is heavy, not easily read from a distance, has mixed fonts, and the correlation between text and image isn’t particularly obvious. Later Gran Fury posters would occasionally be printed in both English and Spanish versions, but not with both languages at once as we see in this busy image.

The poster may not have been completed on time, as it doesn’t seem to have been deployed at the Cosmopolitan protest. Nevertheless, the image occasioned Gran Fury’s first affirmation of collective purpose. Across the bottom of the poster, in type so small it’s almost challenging to decipher even up close, it reads: “Gran Fury is a band of individuals united in anger and committed to exploiting the power of art to end the AIDS crisis.”

Gran Fury is a band of individuals united in anger and committed to exploiting the power of art to end the AIDS crisis.

Gran Fury proved integral to ACT UP’s efforts, supplying pithy slogans and succinct across messaging on posters, stickers, shirts, pins, and billboards. Photojournalists following these protests were keen to document, publish, and thus widely distribute imagery showcasing Gran Fury’s work in newspapers and magazines. The Washington Post even referred to ACT UP as “the best-merchandised revolution in town.”[7] These combined efforts turned out to be highly effective in pushing pharmaceutical companies to lower the price for AIDS-combating drugs.

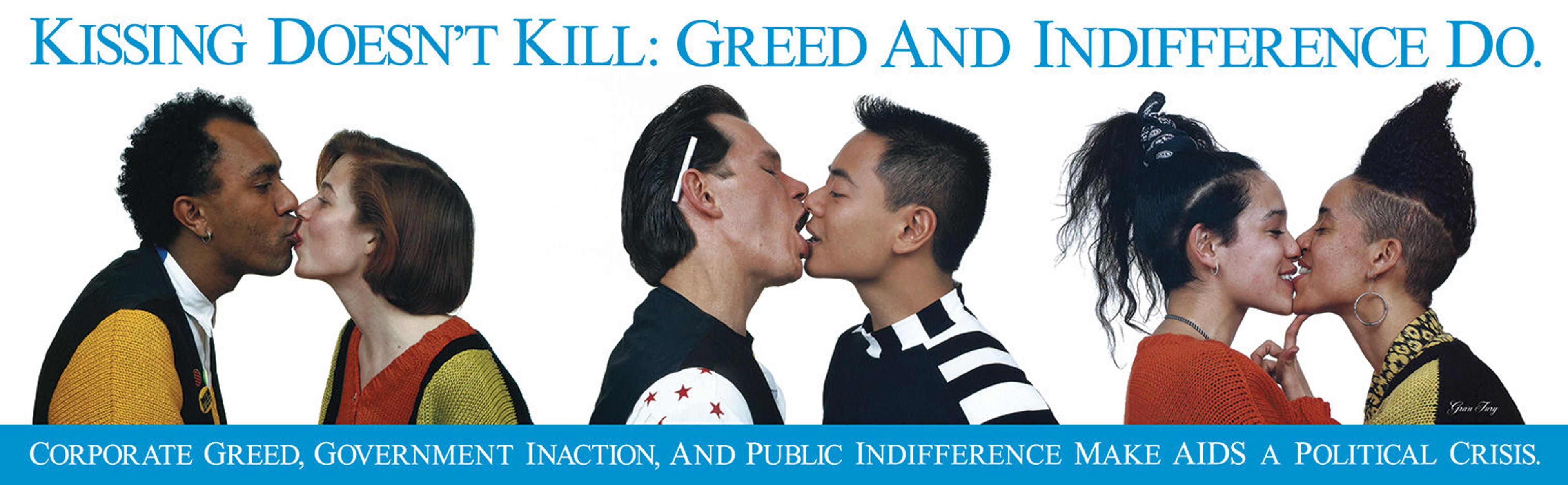

While demonstrating the power of art at a grassroots level, many of their projects employed and relied on a combination of advertising tactics, sometimes even mimicking specific ad campaigns, such as Kissing Doesn’t Kill, which imitated a United Colors of Benetton ad and was designed for buses in New York and London. As a result of Gran Fury’s many aspirations, ACT UP was—and possibly still remains—among the most well-branded protest movements.[8]

Gran Fury (American, active 1988–1995). Kissing Doesn't Kill: Greed and Indifference Do, 1989. Image courtesy of the Avram Finkelstein Archive

Several of the collective’s members had backgrounds in graphic design and advertising, bringing useful skills and tools for disseminating and distributing art (and propaganda) to a wide audience. Instead of deploying the visual language of advertising to sell products, Gran Fury appropriated such tactics in order to present ideas and shift perceptions and public opinion about AIDS. In his book, It Was Vulgar & It Was Beautiful: How AIDS Activists Used Art to Fight a Pandemic, Jack Lowery describes how Gran Fury’s work encourages us to consider the ways in which not all propaganda is alike: “A kind of propaganda that can even repair democracy[…], civil rhetoric is one of the few ways in which marginalized or disenfranchised groups of citizens can reclaim power.”[9]

In an article for October, Douglas Crimp contextualized the collective and their art within a very real fight for survival: “We don’t need a cultural renaissance; we need cultural practices actively participating in the struggle against AIDS. We don’t need to transcend the epidemic; we need to end it.”[10] Despite coming together with a sense of urgency and goals that had little or nothing to do with making art or changing the way people look at art, Crimp’s October article combined with some of the collective’s appropriation work of the early 1980s catapulted Gran Fury, in the words of one former member, from “t-shirts and posters to billboards and international exhibitions.”[11]

While the art world often shuns DIY and ad hoc activist art rooted in political activism and community organizing that seeks to challenge and break from conventions, Gran Fury received institutional exposure as well as national recognition. For example, the collective represented the U.S. at the Venice Biennale in 1990 (alongside Jenny Holzer, Jeff Koons and Cady Noland).

In their quest to propagandize on behalf of people with AIDS, Gran Fury was able to popularize and alter the terms of debate on a range of issues, from the homophobia of the Catholic Church to the profiteering of Big Pharma and the need for nationalized healthcare as a human right—ideas that remain at the forefront of national discourse.[12]

![Blurred, circular image in blue ink showing a person kissing a butt. Text reads "Good Luck [...] miss you, Gran Fury"](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/cctd4ker/production/3a9ec0e03fd7cea2e11e2e7e2e3c1d8544d40e56-1108x1080.jpg?w=3840&q=75&fit=clip&auto=format)

Gran Fury (American, active 1988–1995). Good Luck… Miss You, Gran Fury, 1995. Image courtesy of the Avram Finkelstein Archive

Communication breakdowns and struggles surrounding gender, race, and class contributed to the collective’s dissolution in 1995. According to Gran Fury’s final piece, Good Luck… Miss You, Gran Fury, the atmosphere surrounding the AIDS epidemic had changed and the collective’s original strategies were no longer able to “communicate the complexities of AIDS issues.” The effort became too demanding and routine. Many activists ended up working for institutions and organizations that they had previously been excluded from. This in turn sparked media campaigns that occupied public space previously carved out by Gran Fury, whose activism didn’t die as much as it shifted focus.

In June 2023, The Met collaborated with NYC LGBT Historic Sites for our second annual pride month feature, to produce videos featuring objects from the museum’s collection with connections to places and spaces around the city documented by NYC LGBT. You can hear and watch our discussion here.

Notes

[1] Douglas Crimp, AIDS Demo Graphics (Seattle: Bay Press, 1990), 15.

[2] Tommaso Speretta, Rebels Rebel: AIDS, Art, and Activism in New York, 1979–1989 (Ghent: Mer. Paper Kunsthalle, 2014), 7.

[3] Email exchange with Ian Alteveer, former Aaron I. Fleischman Curator in the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art at The Met, May 19, 2023.

[4] “Actions and Zaps,” Documents, ACT UP, accessed May 29, 2024, https://actupny.org/documents/newmem2.html.

[5] Avram Finkelstein, After Silence: A History of AIDS Through Its Images (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 94.

[6] Jeff Cohen and Norman Solomon, “Cosmo's Deadly Advice To Women About Aids,” The Seattle Times, published July 31, 1993, https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/?date=19930731&slug=1713646.

[7] Paula Span, “Getting Militant About AIDS,” The Washington Post, published March 28, 1989, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1989/03/28/getting-militant-about-aids/c5a168a9-08c5-467f-96c9-d4e29eb1dab3/.

[8] Jack Lowery, It Was Vulgar & It Was Beautiful: How AIDS Activists Used Art to Fight a Pandemic (New York: Bold Type Books, 2022), 3.

[9] Lowery, It Was Vulgar & It Was Beautiful, 5.

[10] “AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism,” October, vol. 43 (Winter, 1987): 7.

[11] “Gran Fury talks to Douglas Crimp,” ARTFORUM, (April 2003), https://actupny.org/indexfolder/GRAN%20FURY_on_ARTFORUM.pdf.

[12] Daniel Marcus, “Read Their Lips: The feats and failures of Gran Fury,” ARTFORUM, published April 8, 2022, https://www.artforum.com/columns/the-feats-and-failures-of-gran-fury-251734/.