Picasso sat very tight in his chair and very close to his canvas and on a very small palette, which was of uniform brown-grey colour, mixed some more brown grey and the painting began.

— Gertrude Stein

This evocative description introduces us to Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso, his cold, spartan studio in Montmartre, and one of the most celebrated portraits of early modernism. It was 1905. The young Picasso had just met Stein, the expatriate American collector, who had recently discovered the artist's new paintings at a gallery in Paris. Picasso was taken by Gertrude and asked to do her portrait even though he was not working from observation at the time. Over a period of three months, in the dead of winter, he stoked his cast-iron stove and welcomed her into his humble atelier. She wore a brown corduroy suit and sat in a large broken armchair. The studio was lively—visitors came and went while Gertrude chatted away with her newfound friend. During intervals of calm, the beautiful Fernande Olivier (Picasso's muse of the moment) read aloud the poems of Jean de La Fontaine.

On the day Picasso began the portrait, Gertrude's brother Leo appeared at the studio with several family members. So impressed with the first sketch, they urged Picasso to leave the image as it was. He shook his head, said no, and carried on.

In the rich mythology surrounding this illustrious collaboration, Gertrude noted that she posed for eighty or ninety sittings. This curious calculation is likely an exaggeration. We know that Picasso painted quickly and intensely, albeit with difficulty. He worked and reworked the canvas over many months.

A photograph of Gertrude Stein's apartment. Over the mantle are Paul Cézanne's Madame Cézanne with a Fan, 1878/88, and Pablo Picasso's Gertrude Stein, 1905–6.

Quite suddenly, in the spring of 1906, he painted out the head, famously saying, "I can't see you any more when I look." He was at an impasse. The portrait of his formidable sitter was halted, at least temporarily. Picasso had struggled with his subject, challenged more by his own investigations as a painter than by the impulse to capture likeness. He knew the portrait would hang in the Stein apartment on the rue de Fleurus, its impact tested by the proximity of Matisse's Fauve portrait of his wife, Amélie, and Cézanne's magisterial image of his wife, Hortense Fiquet. Even beyond the measure of contemporary rivals, Picasso saw himself as part of a lineage of masters reaching back to Raphael. He once told Gertrude, "They say I can draw better than Raphael and probably they are right."

Following a hiatus of several months in the early summer, when Picasso and Fernande traveled to Catalonia and Leo and Gertrude sojourned in Fiesole, Picasso resumed the portrait—but this time without the sitter. Gertrude was still on holiday. Picasso painted in the stylized face with greater sympathy for the Iberian sculpture he had recently observed and various locals he had drawn in Spain than for physical similarity. (In hindsight, we know he was on the eve of painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.) Upon seeing the finished portrait, Gertrude's friends were dismayed by the mask-like severity of the face. Picasso responded, "Everybody thinks she is not at all like her portrait, but never mind, in the end she will manage to look just like it."

Despite the reservations of others, Gertrude herself was very pleased. The portrait was given pride of place in her growing collection. And when Paris faced Nazi occupation in 1939, Gertrude and her partner, Alice Toklas, escaped to their country house, in Bilignin in southeastern France, with only two pictures: the Picasso and Cézanne portraits. As the war continued and money grew increasingly scarce, the time came to sell one of these prized assets. Gertrude found a buyer in Switzerland for Cézanne's portrait of Hortense Fiquet. At some risk to their safety, Gertrude and Alice drove to the French-Swiss border to consummate the sale. When the war ended, they returned to Paris with the beloved Picasso portrait, which rejoined the envied Stein collection of modernist pictures. Soon afterwards, Gertrude died of cancer, leaving her portrait to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was the only picture mentioned in her will.

These two portraits of poet, collector, and salonnière Gertrude Stein were painted within months of each other. Left: Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Gertrude Stein, 1905–6. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 32 in. (100 x 81.3cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Gertrude Stein, 1946 (47.106). © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Right: Félix Vallotton (Swiss, 1865–1925). Gertrude Stein, 1907. Oil on canvas, 39 1/2 x 32 in. (100.3 x 81.3 cm). The Baltimore Museum of Art, The Cone Collection, formed by Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, Maryland (BMA 1950.300). Photograph © Mitro Hood

Sometime while Gertrude was sitting for Picasso, she introduced him to the diffident artist Félix Vallotton. We know very little about Gertrude's association with Vallotton, but imagine that he saw and was moved by the portrait-in-progress and thought he would try his own hand at the same subject. It was a bold initiative, for Vallotton's previous sitters had all been friends or family. Such familiarity was both a comfort and a tool, much as it was for Cézanne through his lifetime. Gertrude was fond of Vallotton and agreed, once again, to sit for her portrait. Describing the experience in her autobiography (where her observations are written in the third person), she noted that Vallotton had an entirely different approach and time clock!

When he painted a portrait, he made a crayon sketch and then began painting straight across. Gertrude Stein said it was like pulling down a curtain as slowly moving as one of his Swiss glaciers. Slowly he pulled the curtain down and by the time he was at the bottom of the canvas, there you were. The whole operation took about two weeks and then he gave the canvas to you.

Are these remarks apocryphal? It is hard to imagine Gertrude Stein inventing Vallotton's eccentric process for the sake of her own writing. On the other hand, how could the artist work from left to right in a vertical orientation? Granted, he was not preoccupied with color relationships, and his palette was fairly limited. Unlike Picasso's nervous, energetic brushwork, Vallotton's touch is even, uniform. Vallotton adheres to the presumed expectations of portraiture. He describes volume, lays in facial idiosyncrasies, and seems to want to please his sitter.

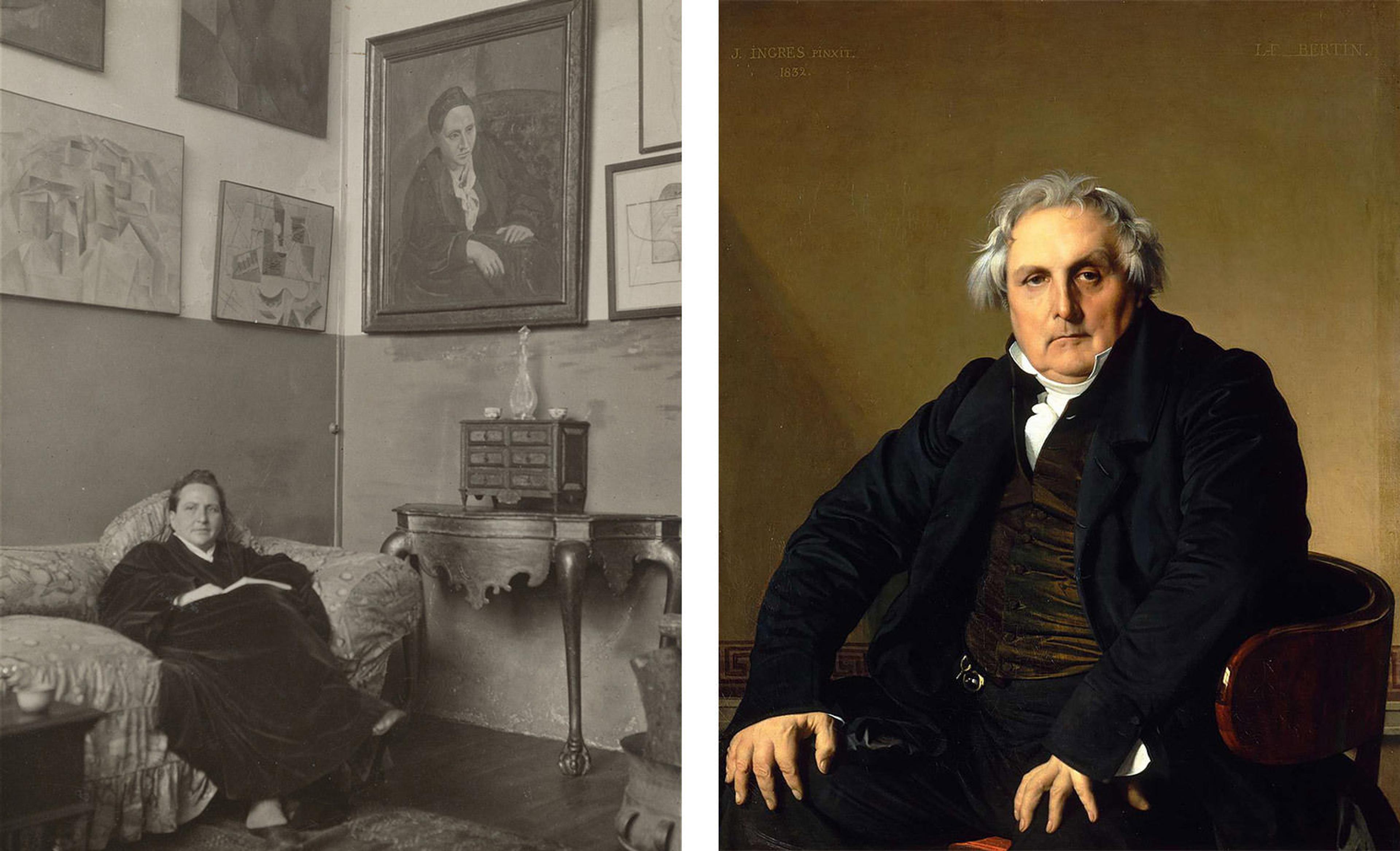

Left: Gertrude Stein in her Paris studio with Picasso's portrait above her, unknown photographer, c. 1903. Right: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French, 1780–1867). Portrait of Louis-François Bertin, called Bertin the Elder (1766–1841), 1832. Oil on canvas, 46 x 38 in. (116 x 95 cm). The Louvre, Paris (R.F. 1071). Public-domain image via Wikimedia Commons

Gertrude did not care for the portrait. She complained that it did not possess enough elegance. Others agreed. When Vallotton submitted the painting to the Salon of 1907, it was met with ire. Critics said it was charged with vulgarity, cold and unfeeling draughtsmanship, and that it lacked brilliant color and sufficient photographic realism. Edouard Vuillard, Vallotton's lifelong friend, said the portrait resembled Madame Bertin—a witty allusion to Ingres's famous portrait of the writer Louis-François Bertin, now in the Louvre. In fact, both portraits of Gertrude Stein have been compared to the seated Monsieur Bertin. Vallotton's comes closer. In it, Gertrude appears full-bodied, still sporting the brown corduroy suit. Her pyramidal form seems to have more to do with Picasso's rendering than with any basis in visual reality.

Félix Vallotton (Swiss, 1865–1925). The Lie (Le mensonge), 1897. Oil on cardboard, 9 7/16 x 13 1/8 in. (24 x 33.3 cm). The Baltimore Museum of Art, The Cone Collection, formed by Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore Maryland, (BMA 1950.298). Photograph © Mitro Hood

Fortunately for Vallotton's reputation, Claribel and Etta Cone of Baltimore fell for the portrait, as they did for his tabletop sculpture and famed Intimité jewel, The Lie (1898). They bought the portrait from Gertrude in 1926 for ten thousand French francs, far more than they had paid for any other work by Vallotton. This inflated offer may have been a gesture of generosity toward the financially strapped Stein family as much as a sign of eagerness to own the picture. The portrait now resides in the Cone Collection at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Both portraits of the inimitable Gertrude Stein found their way to the United States, a fitting legacy for a woman born and educated on the East Coast. Painted just months apart and presented to the sitter as gifts, they have not been shown under one roof since 1926. The Met's current exhibition Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet has occasioned their reunion.