The Adoration of the Magi is the name given to the scene in Christian art following the birth of Jesus in which the three Magi are represented as kings. After following the Star of Bethlehem to find Jesus, they present gifts of frankincense, myrrh, and gold, and worship him in recognition of his divinity (Matthew 2:11). Late medieval and early Renaissance depictions of the Adoration show the three kings coming from three different parts of the world: the youngest from Africa, the oldest from East Asia, and a middle-aged king from Europe. Many of these scenes depict the youngest king as a Black figure positioned farthest in the composition from Christ. Why is he the youngest? Why is he farthest away? What can these details tell us about European views of Black people during the late medieval and early Renaissance periods?

Proximity to Christ and the African King

One potential explanation for the African king’s distance from Christ in many of these works is that since the Black Magus is the youngest, he must also be the farthest away. This explanation makes sense since the oldest king is traditionally closest to Christ. However, when we consider early medieval representations of the Adoration where all three kings were depicted with European features, age did not seem to matter. In these works, age is indicated by each king's amount of facial hair, where the oldest has the most and the youngest has the least or none.

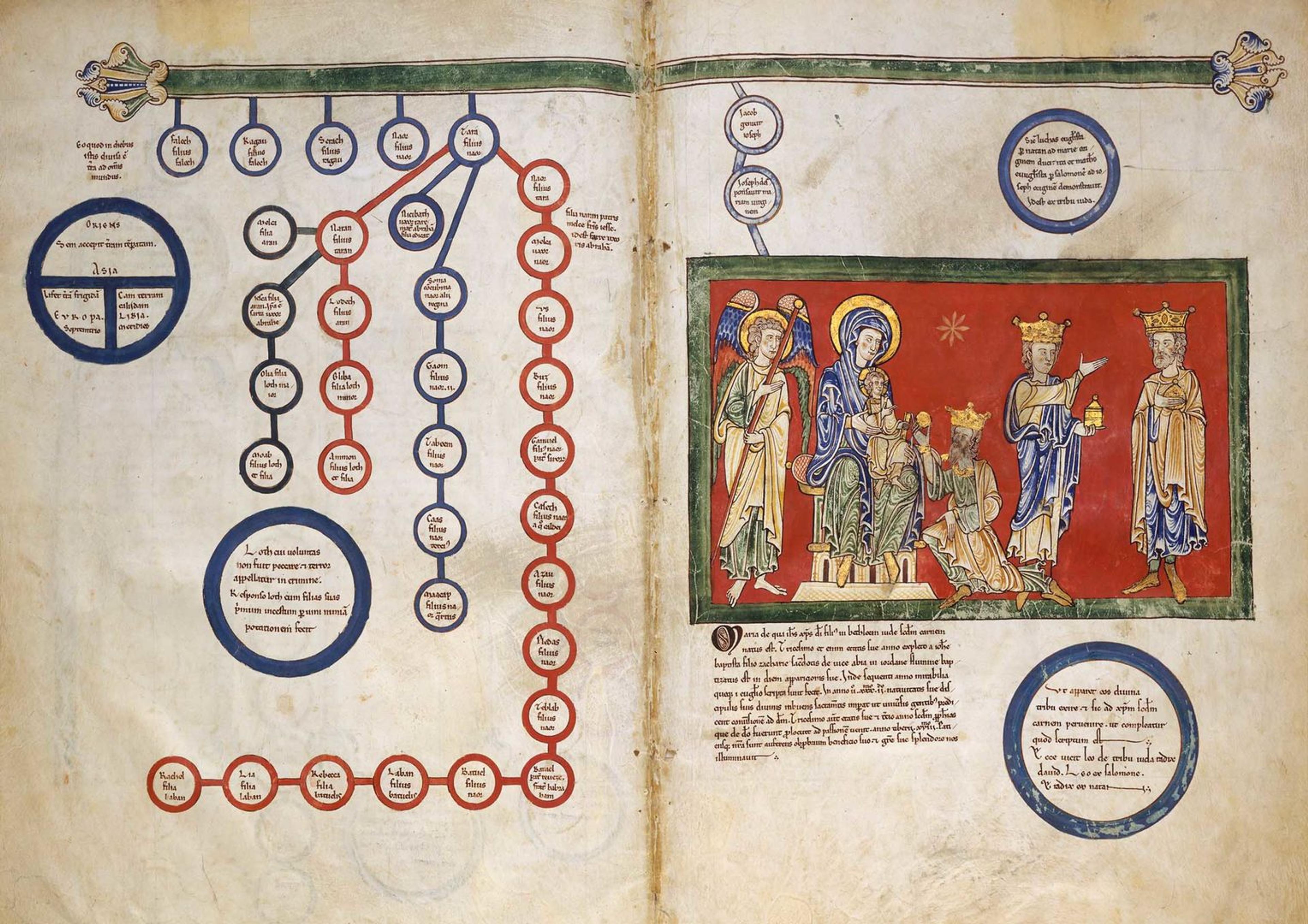

Leaves from a Beatus Manuscript: Bifolium with part of the Genealogy of Christ and the Adoration of the Magi. Spanish, ca. 1180. Tempera, gold, and ink on parchment, Overall (folio): 17 1/2 x 11 7/8 in. (44.4 x 30 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Cloisters Collection, Rogers and Harris Brisbane Dick Funds, and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1991 (1991.232.2a-d)

This illustration from a Spanish Beatus manuscript (ca. 1180) shows three kings presenting gifts to Christ, who is seated on the lap of the Virgin Mary. An angel stands at left, and the Star of Bethlehem—said in the Gospel of Matthew to have guided the kings to Christ—hovers in the center of the image. Gold leaf is abundant, typical of Christian art during the medieval period. There are gold halos around the heads of the Virgin Mary, Christ, and the angel; the crowns of the kings and the containers of the gifts are also gold. While most Adoration scenes depict the kings close to Christ, appearing from oldest to youngest, this work presents a different narrative.

Three kings with European features are represented, each with different beard lengths. The oldest king (with the most facial hair) kneels before Christ, as is customary, while the king with no facial hair (indicating his relative youth) is positioned directly behind the kneeling king. Following the youngest king is a figure with a moderate amount of facial hair in comparison to the others. If age were truly the deciding factor in the kings’ locations in respect to Christ, then in this painting the youngest king ought to be last. But only since the popularity of the Black Magus, who is often depicted in European paintings as the youngest, do we see age dictate the kings’ proximity to Christ.

The Increased Presence of African Representation in Medieval Art

The integration of Black representation into scenes of the Adoration of the Magi occurred gradually. If Black kings were not included, one or all kings might be depicted with Black servants. While European paintings showed that Black people were part of medieval societies, these representations have the potential to shed light on European attitudes toward increasing racial diversity during this period.

Neapolitan Follower of Giotto (Italian, active second third of the 14th century). The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1340–43. Tempera on wood, gold ground, Overall, with engaged frame, 26 1/8 x 18 3/8 in. (66.4 x 46.7 cm); painted surface, including tooled border, 21 3/8 x 15 in. (54.3 x 38.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.9)

The Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1340–43) by a Neapolitan follower of Giotto shows three Magi adorned in golden robes, two angels at right standing behind the seated Virgin Mary and infant Christ, and three Black attendants presented at a diminutive scale in the bottom left corner. All figures (excluding the three Black figures) have golden halos around their heads, a symbol of holiness in European art. The absence of halos around the heads of the attendants implies that these figures lack the characteristics required to attain holiness, a closeness to Christ that the others possess. The three Black figures are also significantly smaller in comparison to other figures in the composition. While they are included in this work, the painting works visually to de-emphasize their presence.

This painting is an example of racism that existed during the medieval period. Some may say it depicts the kind of work Black people held during this period, but the artist creates a clear distinction between those who are considered holy and pure and those who are not. The absence of halos around the servants’ heads, combined with their being farthest from Christ, suggests that Black people during the Middle Ages were seen as less holy than most of civilization.

The Inclusion and Exclusion of Black Figures

Not until the late medieval period did the representation of one of the three Magi as a Black king grow prevalent. While Black people increasingly occupied various roles in medieval society, European views toward people who were neither white nor Christian were rife with discrimination. The inclusion of Black people in depictions of the Adoration indicate European artists' changing views toward diversity and their desire to observe the world around them with increasing verisimilitude. But it also reveals an early form of token Black representation—that is, the presence of a Black figure hints at diversity even as racist attitudes prevail.

Justus of Ghent (Joos van Wassenhove) (Netherlandish, active by 1460–died ca. 1480). The Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1465. Distemper on canvas, 43 x 63 in. (109.2 x 160 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of George Blumenthal, 1941 (41.190.21)

Let's turn to another Adoration scene painted by Justus of Ghent (active ca. 1460–1480). There are three Black figures in this composition: a king, his servant handing him a gift, and a member of the crowd. (The two Black figures whose faces are visible in a frontal view look similar, which raises the question of whether the artist used the same model for each.) Set against a palette of brown and neutral shades, elements in green, red, and blue draw the viewer's gaze to different figures in the painting. The composition follows the common tropes we see in European depictions of the Adoration, including the detail of a Black king situated farthest from Christ.

Depictions of the Black Magus in Western art are found in museum collections all over the world. By looking closely, identifying patterns, and questioning the placement or size of one figure in relation to another, we can begin to understand how social dynamics translate into visual culture. Despite the presence of Black Christians throughout Europe in the Middle Ages, these popular works of art employed a specific vocabulary to distinguish Black people from their white Christian counterparts, presenting them without halos and placing them in marginal positions. The circulation of these images, and the messages they contain, have undoubtedly shaped (and continue to shape) the way people subconsciously or consciously perceive race today.

While scholarship in the field is ongoing, it is helpful to consider documentary records of Africans in Western Europe, as well as medieval texts that provide insight into the perception of race in the Middle Ages. (One particularly interesting work is the English chivalric romance The King of Tars, which the scholar Cord J. Whitaker discusses in his 2019 book Black Metaphors: How Modern Racism Emerged from Medieval Race-Thinking.) While it may seem anachronistic to use words such as "racism" to describe art in the Middle Ages, it is not. The works of art in this essay are premodern examples of othering. Recognizing that these forms of racism existed in the past may allow us to expand and reframe contemporary discourse around the legacy of racism.