If you’re mourning in New York City, there are three helpful pilgrimage sites:

1. An old cemetery, ideally a star-studded one like Green-Wood, to remind you that every one of us will die or has died, including Civil War generals and abstract artists, baseball players and composers—even seemingly immortal politicians like Boss Tweed.

2. Kossar’s Bagels & Bialys for comfort rugelach—or Zabar’s if you’re uptown.

3. Gallery 102 of The Met, Raemkai’s Tomb.

Like a lot of kids, I was obsessed with ancient Egypt. The Met’s Egyptian wing was our mecca. Entering it, you face the Tomb of Perneb, built ca. 2381–2323 BC, and you get to go inside it. (Well, you did before COVID-19—and if you want to see smoke come out of ears, ask my teenager how he feels about that tomb’s new protective rope.) For those moments inside the tomb, it felt like you weren’t in the middle of a noisy city but alone in the Egyptian desert.

Next stop: turn to the right and head through the doorway labeled “Old Kingdom Egypt,” for the less flashy Tomb Chapel of Raemkai.

Tomb Chapel of Raemkai, ca. 2446–2389 B.C., Dynasty 5, Limestone, paint, Chapel: H. 213.4 x N-S axis: 434 x E-W axis: 117 cm (84 x 170 7/8 x 46 1/16 in.); Entrance: N-S. 55 x E-W. 137 cm (21 5/8 x 53 15/16 in.), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1908 (08.201.1a–i)

Here you have a bit more space to maneuver. The hieroglyphics set behind plexiglass are clear five thousand years later. This is the perfect place to make use of the yellow Fun with Hieroglyphs kit. In grade school, I used it with limited success to interpret the cartouches and with glee to render my friends’ names in shapes.

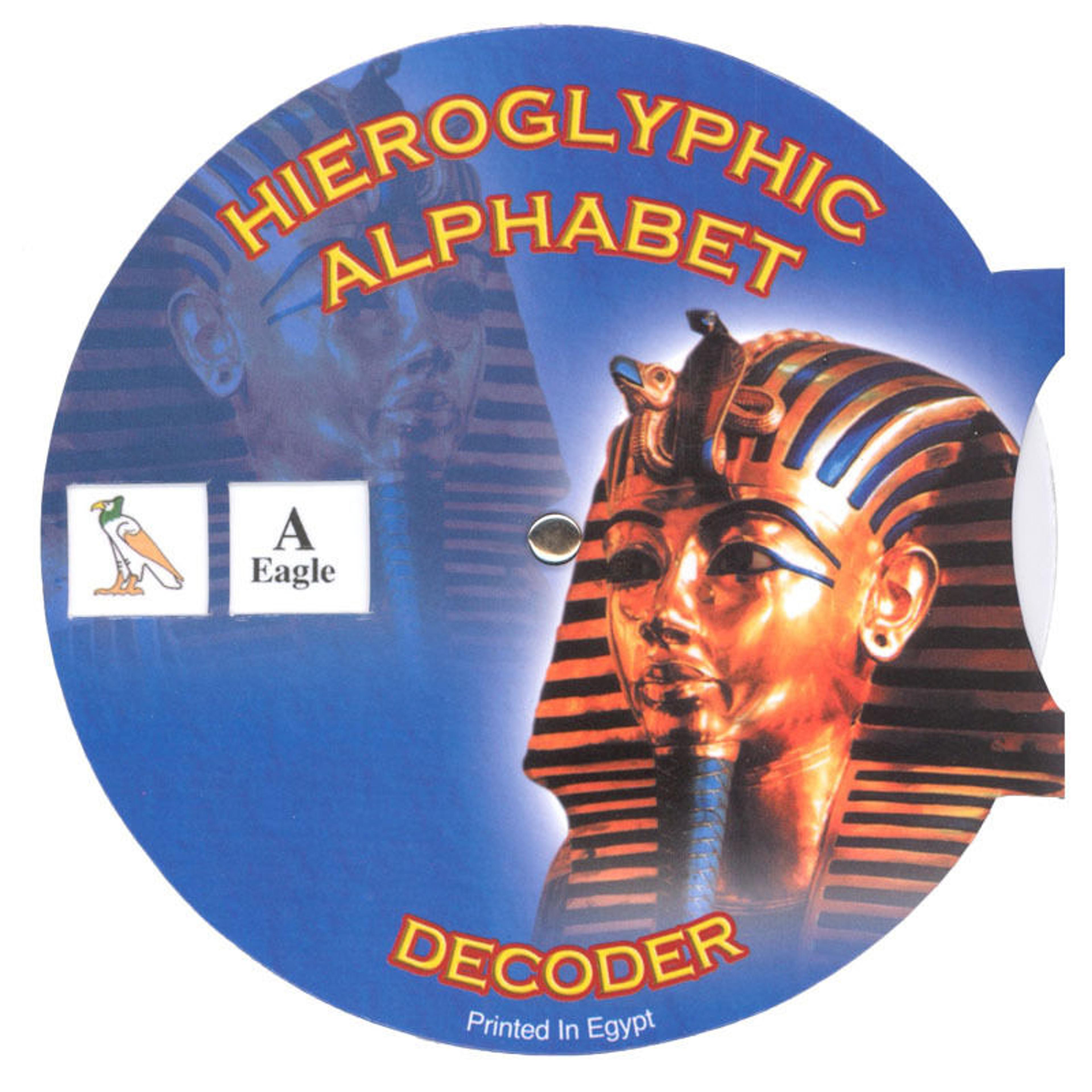

When I became stepmother to a six-year-old in my mid-twenties, I took my stepson here and bought him a Hieroglyphic Alphabet Decoder wheel in the gift shop. We walked around calling out, “Look! Snail-snake-foot!” My name is vulture-hand-vulture. His starts with a leg. There are worse ways to spend an afternoon with a kid than playing armchair-linguist. I did the same thing with my son when he was a little boy.

A Hieroglyphic Alphabet Decoder, once sold in the gift shop.

Those kids are now twenty-eight and sixteen, and much taller than I am. You can no longer get a Hieroglyphics Alphabet Decoder in the gift shop now that there are translators on the internet. Still, I bought one for my goddaughter for ninety-nine cents on eBay.

What I remember from those days is that birds filled every wall—the Egyptians were obsessed with birds—and they seemed to mean many things. Sparrows could be “small” or “bad” (because, we learned, they were pests that ate farmers’ grain). But what they mostly symbolized was regeneration and rebirth.

Tomb Chapel of Raemkai: East Wall, ca. 2446–2389 B.C., Dynasty 5, Limestone, paint, 117 cm (84 x 170 7/8 x 46 1/16 in.), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1908 (08.201.1e)

Last week, as I was driving up to be with my father for the last time, a little brown bird flew into my windshield. It felt like a bad omen.

A day later, I sat with him as he was dying. In the middle of the night, he asked how long it would take.

“As long as you need,” I said.

Today, having been to a graveyard and eaten too much cinnamon rugelach, I went alone to The Met on a cold weekday afternoon. It was the first time in forever I’d been there without a child pulling me from room to room, so I could read every plaque.

Engraved boats sail along the doorway west into Raemkai’s tomb. Within, a bull and cow mate. A calf is born. Men gut fish. Bread is baked. An ox is slaughtered as men grapple with the carcass. And of course there are birds—so many birds.

On the west wall, there is what’s known as a false door. This was the Egyptians’ portal to the other world, where people would bring offerings and the dead could greet their guests.

Tomb Chapel of Raemkai: False Door on West Wall, ca. 2446–2389 B.C., Dynasty 5, Limestone, paint, 137 cm (21 5/8 x 53 15/16 in.), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1908 (08.201.1e)

From The Met, I walked the three and a half miles home to the apartment I just moved back into, the same apartment I grew up in, the one my parents moved into when they fell in love in 1973. I entered the not-false front door through which this week have passed flowers, cheesecake, and stacks of condolence cards.

I sat in what used to be my father’s office and stared out the window. A bird like some of the ones on the wall of Raemkai’s tomb landed on a branch. I thought about what the decoder wheel told us they meant: life.