New York City has long been an epicenter of LGBTQIA+ history and art, yet the role of queer artists in shaping the cultural life of the city has been largely overlooked. Today we shine a light on a few of the many members of the LGBTQIA+ community who have made New York City and the global art world what it is. Please join The Met and the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project on a virtual walking tour of queer New York.

The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project documents historic places connected to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people in New York City and tells the often-untold stories of their influence on American history and culture.

In celebration of Pride Month, members of The Met’s LGBTQIA+ community reflect on the legacy of several queer artists in the Museum’s collection and, with the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, highlight the spaces where they lived, worked, and drew their inspiration.

Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland: Residence and Studio

50 Commerce Street, West Village, Manhattan

Christopher D. Brazee/NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, 2016

From 1935 to 1965, photographer Berenice Abbott (1898–1991) and art critic Elizabeth McCausland (1899–1965) lived and worked in two flats they shared on the fourth floor of 50 Commerce Street.

Around the time of her move here, Abbott received funding from the Federal Art Project (a division of the Works Progress Administration) for her “Changing New York” series to document the ever-changing metropolis. For the next three years, she took hundreds of photographs of city life and architecture across all five boroughs. Abbott printed more than three hundred images for the finished project, the now-classic book Changing New York (1939). McCausland provided the text for that book, and other important works of art history and criticism.

— NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

Left: Berenice Abbott in Paris in 1928. Credit Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone, via Getty Images. Right: Berenice Abbott (American, 1898–1991). Djuna Barnes, 1925. Gelatin silver print, 8 7/8 x 6 3/4 in. (22.6 x 17.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joyce and Robert Menschel Gift, 1987 (1987.1002) © Berenice Abbott / Commerce Graphics Ltd. Inc.

Much has been written about Changing New York and its enduring appeal as an early feat of documentary modernism in America, less so about the same-sex partnership that ultimately saw the project through.

Changing New York sought to capture New York rising from the ashes of the Great Depression. The book could not have come together the way it did without the tried-and-true technique of sliding into someone’s DMs. Throughout her career, McCausland wrote about and championed female artists with the aim of bringing their art out of the home and repositioning it in the landscape of social issues and feminism.

In 1934, McCausland, wrote a glowing review of Abbott’s photographic oeuvre. Abbott had started out as a lab assistant to Man Ray in his Paris studio around 1924–26, using her lunch hour to portray friends from the flourishing local homosocial community of artists, writers, and thinkers. Her subjects included Jane Heap, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Jean Cocteau.

McCausland noted, while reflecting on Abbott’s work, that “the social muse and the artist can consort without either yielding position, the idea not subservient to the medium, the medium not the slave of communication….” In a letter of thanks to McCausland, Abbott wrote, “I can say truthfully that I consider your article the first intelligent one on my work that has appeared in this country.” She concluded: “I thank you for your appreciative article and sincerely hope that I may have the pleasure of meeting you sometime when you are in New York. Your approval of my pictures has been most encouraging.”

McCausland moved to New York the following winter to seek Abbott out, and to center herself in the art world she wrote about. Lives were transformed by the ensuing thirty-year partnership. The two women were devoted companions and professional soul mates, living and working together at 50 Commerce Street from 1935 until McCausland’s death in 1965.

Most of the original captions that McCausland wrote for the final ninety-seven photographs included in Changing New York were deemed too politically and socially radical for the editors of the project, who were keen to present the results as a more traditional city guide. Despite this censorship, Changing New York remains an epic outsider art project thought up by a couple of queer, midwestern women who were both champions of the underrepresented and disadvantaged. Readers are invited to ponder the thrills and threats of modernity alike. While refusing to offer the viewer much sentimental comfort or any solutions to the loneliness of city life, the book certainly romanticizes the notion that since New York City embodies everything all at once, nothing matters nor is ever truly lost. We are free to go our own way and do with it what we please.

— Jasmine Kuylenstierna, Collections Management Associate, Department of Drawings and Prints

Watch Kuylenstierna discuss Berenice Abbott and New York City with The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project on Instagram.

Richmond Barthé: Green Pastures: The Walls of Jericho Mural

Kingsborough Houses, Brooklyn

Ken Lustbader/NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, 2018

In 1929, the artist Richmond Barthé (1901–1989), moved to New York City to join the artistic and cultural scene known today as the Harlem Renaissance, entering established networks of gay social circles. Although he never publicly revealed his homosexuality, Barthé’s sculptures often display homoerotic themes that exploit the Black male nude for its political, racial, aesthetic, and erotic significance.

Barthé’s largest work, and his first in relief, was the cast-stone frieze Exodus and Dance (completed 1939), which was originally intended for the Harlem River Houses, one of the nation’s first federal public housing projects specifically built for African Americans. Through the Works Progress Administration, he was hired as part of a team of sculptors commissioned to create public art for that project. Barthé designed a site-specific work for the back wall of an amphitheater that he envisioned would be used for music, dance, and theater performances. Barthé created scenes using his best-known subject matter: Biblical imagery and African dance. The left side of the frieze was inspired by Marc Connelly’s 1930 Pulitzer Prize–winning play The Green Pastures, which portrays episodes from the Old Testament through the eyes of an African American child. The right side, where the influence of Art Deco design is fully realized, shows African dancers inspired by David Wendell Guion’s 1929 ballet Shingandi come to life.

Months after the Harlem River Houses opened, Barthé’s panels were still in storage since the amphitheater project was never built. In 1941, the panels were installed without his consultation on one of the main walks at the Kingsborough Houses. The work was renamed Green Pastures: The Walls of Jericho.

Barthé’s other public works in New York City include the bas-relief effigy on the Arthur Brisbane Monument, located at Central Park’s Fifth Avenue perimeter wall (at East 101st Street), and the busts of George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington at the Hall of Fame for Great Americans, located on the grounds of Bronx Community College.

— NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

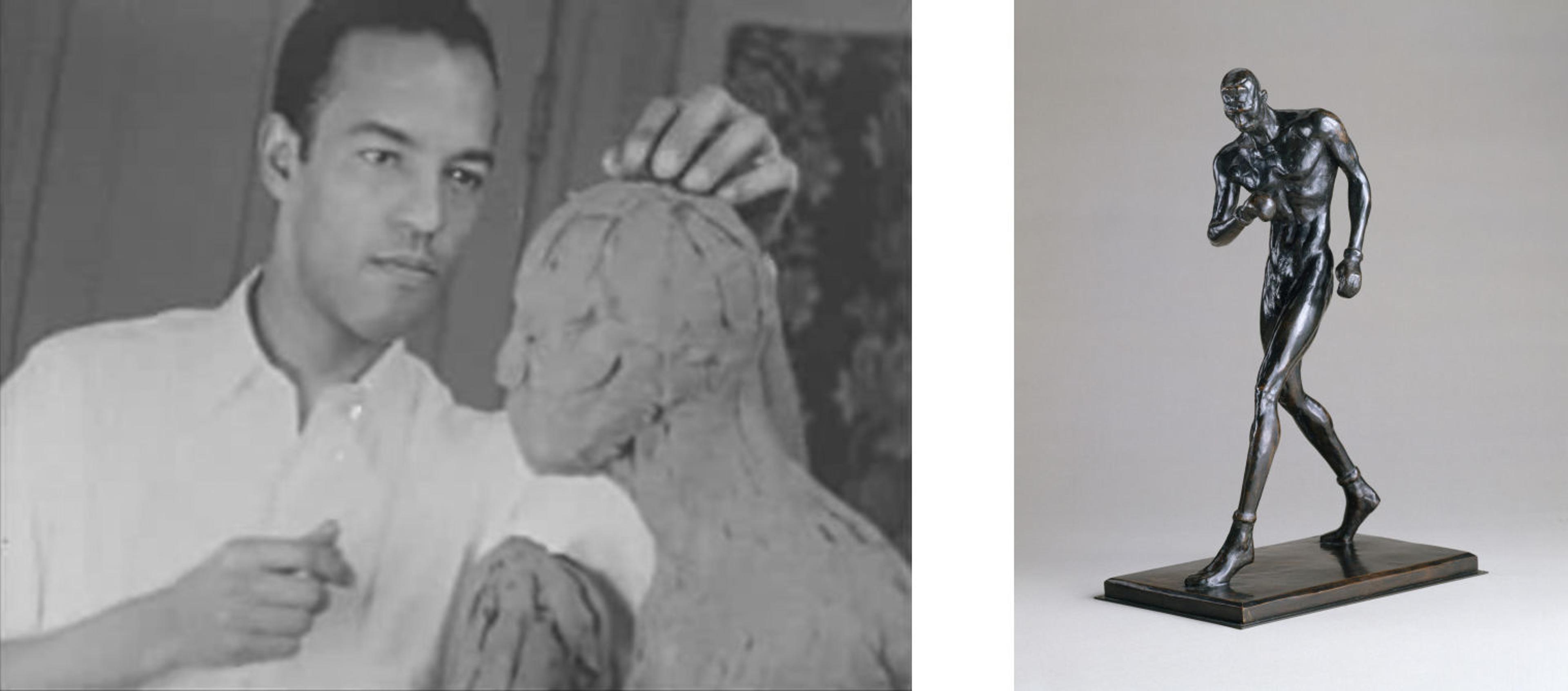

Left: Screen capture of Barthé working in his studio from the silent documentary A Study of Negro Artists, filmed by Jules V.D. Ducher, 1935. Courtesy Wikipedia Commons. Right: Richmond Barthé (American, 1901–89). Boxer, 1942. Bronze, 18 1/4 × 7 × 12 in., 13 lb. (46.4 × 17.8 × 30.5 cm, 5.9 kg). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1942 (42.180)

A prominent figurative sculptor of primarily Black subjects throughout the mid-twentieth century, Barthé produced Boxer (1942) from memory. While the sculpture’s descriptive title renders its subject anonymous, this work commemorates the physique and skill of “Kid Chocolate,” the successful Cuban lightweight prizefighter whose given name was Eligio Sardiñas Montalvo (1910–88). Barthé depicted Montalvo in elegant contrapposto, twisting and turning simultaneously in two directions, while perched high on the balls of his feet. Attenuated limbs and overall elongated proportions effectively convey, even enhance, the implied agility of this athlete, who, the artist later recalled, “moved like a ballet dancer.” One of many nude and semi-nude male figures Barthé produced, the sensuous Boxer alludes discretely to the artist’s homosexuality, about which he was necessarily circumspect throughout his life.

The Met acquired Boxer from its 1942 Artists for Victory exhibition of contemporary American art, where Barthé’s submission received the Sixth Place Purchase Prize in sculpture. The Met also awarded and purchased Jacob Lawrence’s Pool Parlor (1942) from this exhibition, and, thus, Lawrence and Barthé entered the collection at the same time as among the earliest Black modern artists to break this notable barrier. That said, the wartime context of these achievements must be considered critically, as the cultural impulse to publicly recognize Black talent could be and was utilized to burnish the veneer of American democratic ideals and as means to throw the racism of Nazi Germany into high relief.

Boxer later featured in another important, transformational exhibition, Two Centuries of Black Art, the first comprehensive survey of African American art curated by the groundbreaking scholar and educator David Driskell (1931–2020), which toured four venues in 1976–77. Aaron Douglas’s powerful painting Let My People Go (ca. 1935–39), which The Met acquired in 2015 in renewed efforts to strengthen its collection in Harlem Renaissance art, also appeared in this exhibition.

— Randall Griffey, Curator, Department of Modern and Contemporary Art

Watch Griffey discuss the relationship between Barthé’s sculpture and his public work with The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project on Instagram.

Keith Haring: Crack is Wack Mural and Playground

Harlem River Drive at Second Avenue and East 128th Street, Harlem, Manhattan

Keith Haring, CRACK IS WACK MURAL, FDR, October, 1986. Photograph: Tseng Kwong Chi © Muna Tseng Dance Projects, Inc. Art: © Keith Haring Foundation

The Crack is Wack mural was painted on both sides of a concrete handball court wall by the openly gay artist Keith Haring. Haring’s legacy is closely tied to his public art, which first brought him attention in the early 1980s with his temporary chalk drawings on advertisement panels on the walls of the city’s subway platforms.

Crack is Wack showcases his signature style for which Haring became known around the world in the 1980s. Created at the height of the crack epidemic, the mural was dedicated to Haring’s studio assistant, Benny Soto, a gay Puerto Rican teenager from the South Bronx who was then addicted to crack; it served to caution other young people from taking the dangerous drug. As with his works created in the fight against AIDS, the piece exemplifies how Haring used art to support causes he believed in and to express his frustration with government officials and their slow response in addressing these crises.

Haring created the first version of the mural on June 27, 1986, without permission from the city’s Department of Parks and Recreation. He was promptly arrested for vandalism but was later released. While Haring was in police custody his original mural was painted over. However, the department’s commissioner later asked Haring to paint a new mural, which he did on October 3, 1986. This is the version, using the same style and messaging as the original but in a different arrangement, that survives today.

During this period, Haring had an art studio on the top floor of 676 Broadway in Noho, where the Keith Haring Foundation is still located. The existence of Crack is Wack today is due in large part to the Department of Parks and Recreation and the Keith Haring Foundation, which have overseen several restorations of the mural.

In the summer of 1987, a year after Haring created Crack is Wack, he painted the Carmine Street Mural next to the public pool at the Carmine Street Recreation Center (now the Tony Dapolito Recreation Center) in Greenwich Village. This piece and his Once Upon a Time mural in the (now former) second-floor men’s bathroom at the LGBT Community Center also survive. Haring created these three murals in the years leading up to his untimely death, aged thirty-one, from AIDS-related complications in 1990.

— Amanda Davis, Project Manager, NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

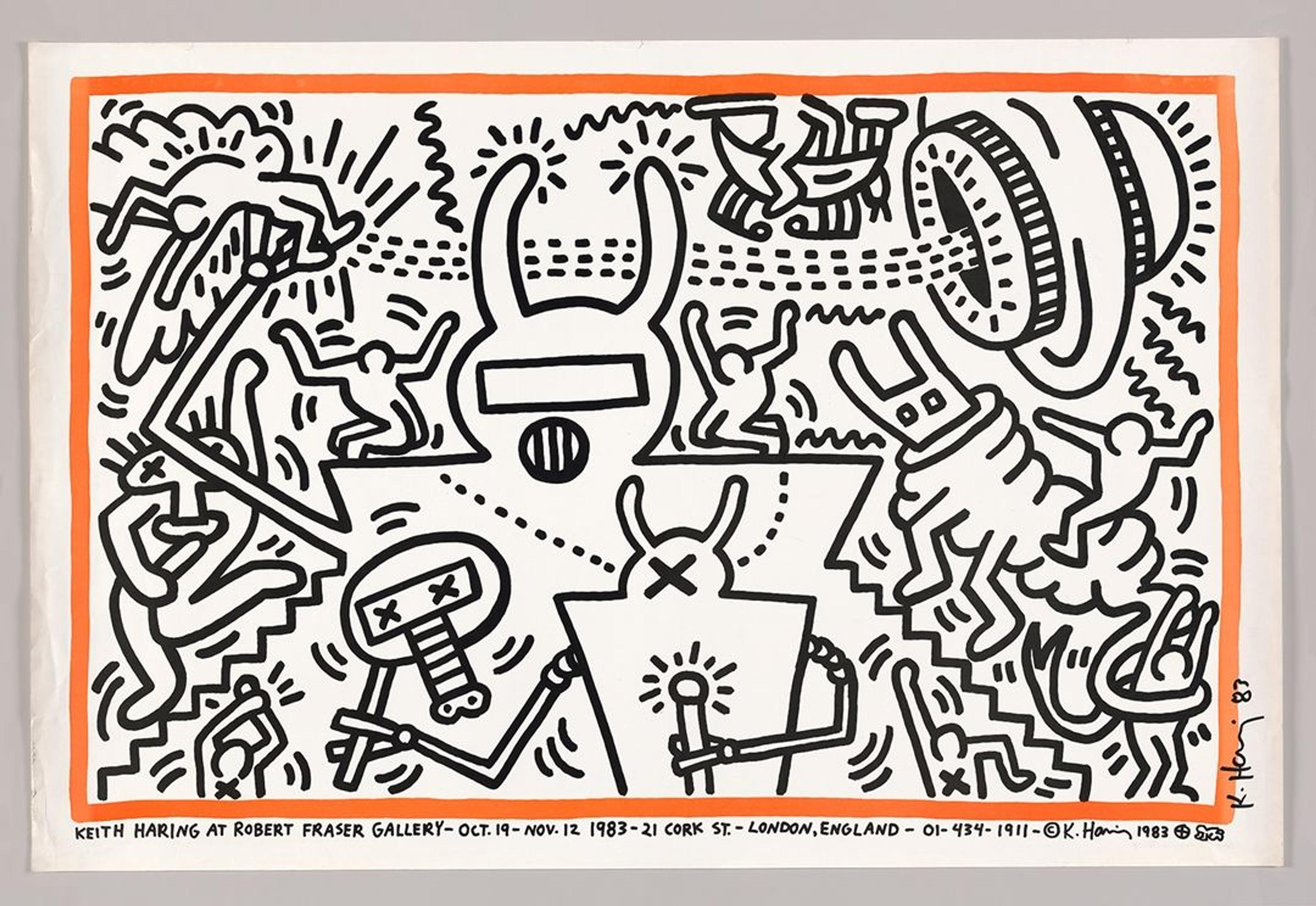

Keith Haring (American, 1958–1990). Untitled, 1983. Offset lithograph, 40 × 26 1/2 in. (101.6 × 67.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Sheena Wagstaff, 2015 (2015.618.4)

Keith Haring was a prolific and influential artist known for his graphic sensibilities and inventive depictions of abstracted human figures. Haring was born and raised in Pennsylvania and developed a knack for cartoon art, which started a lifelong creative journey that led him to reach the broadest audience possible. He made his mark in the art world after moving to New York City in the late 1970s and continued his intense art practice throughout the ’80s. Haring often addressed societal concerns such as drug addiction and AIDS awareness throughout his career. The artist’s ties to the inner city, and the known dangers that drug use can inflict on communities, led him to create his 1986 mural, “Crack is Wack.” As well as working on site-specific locations, Haring also created many other forms of artworks including numerous paintings, drawings, and prints. Haring’s art is featured in numerous galleries and museums around the world, including an untitled print in The Met’s collection. It depicts a spaceship with many tightly-grouped figures actively engaged in futuristic, combative activity.

— Arthur J. Polendo, Senior Departmental Technician, The American Wing

Watch Polendo discuss details in Haring’s artworks with The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project on Instagram.

Peter Hujar and David Wojnarowicz: Residence and Studio

181-189 Second Avenue, East Village, Manhattan

Christopher D. Brazee, NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, 2016

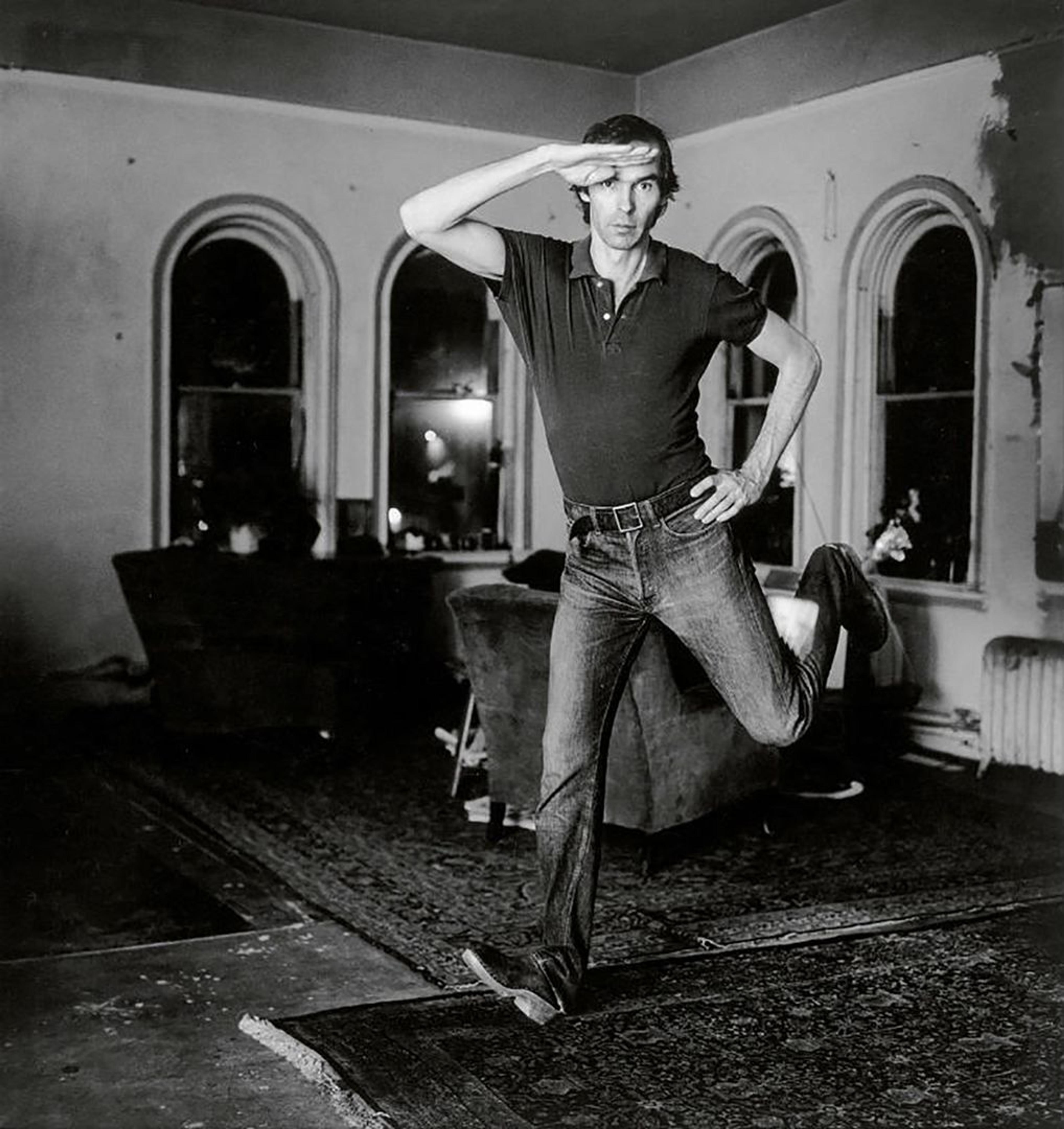

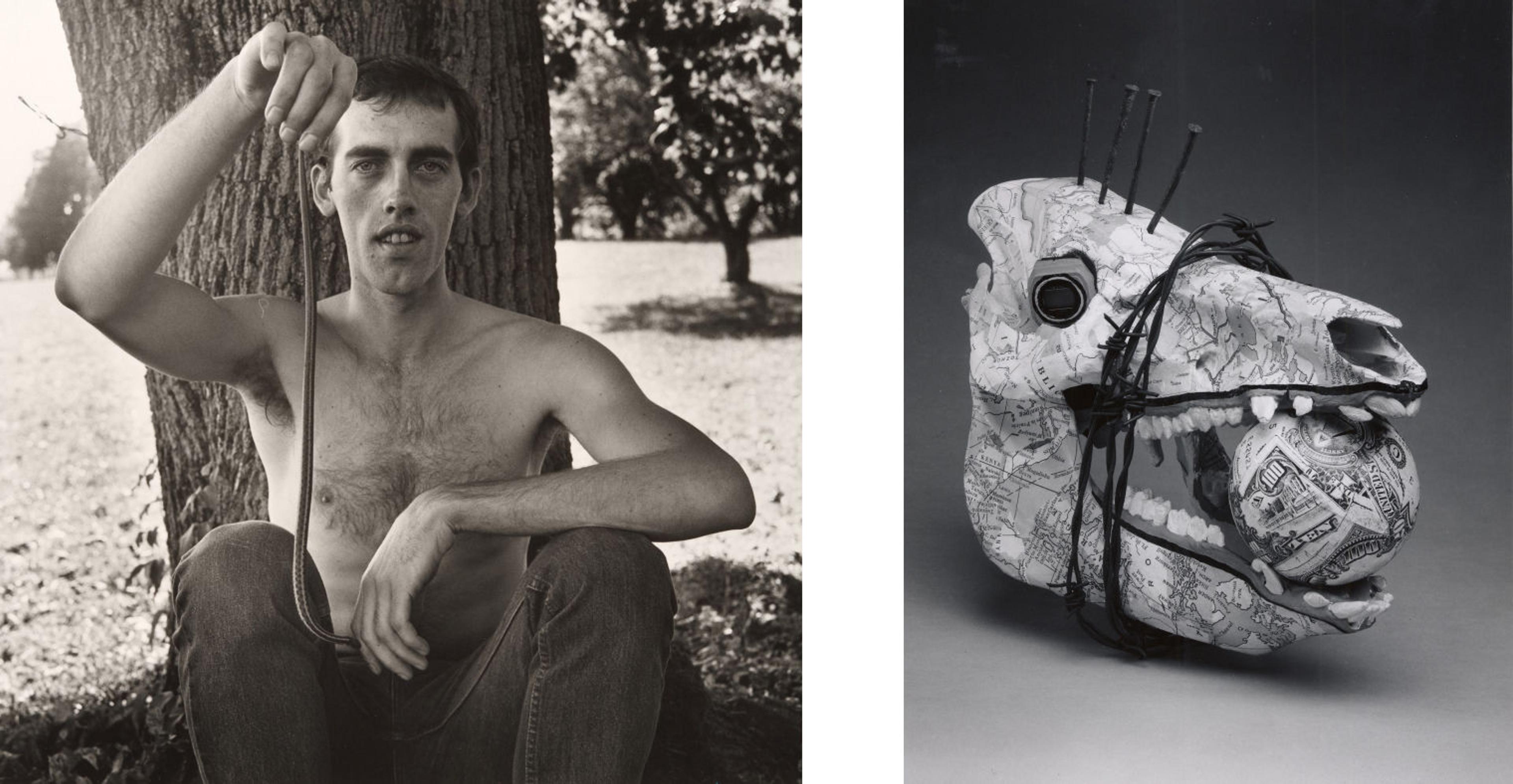

Photographer Peter Hujar (1934–1987) lived and worked in a loft on the second floor of the historic theater at 189 Second Avenue from 1973 until his death in 1987. A stalwart of the Lower East Side art scene, Hujar often donned the role of tutor or parental figure to up-and-coming artists. Hujar made portraits up until his AIDS diagnosis, but also captured street scenes of the decaying New York of the 1970s and ’80s, as well as the uninhibited queer life that blossomed at the piers on Manhattan’s west side.

Hujar is now partly remembered for his intense relationship with David Wojnarowicz (1954–1992), for whom Hujar was an unparalleled source of support, inspiration, and tutelage. Hujar died, aged fifty-three, from AIDS-related complications in 1987.

Taken in Hujar’s loft at 181-189 Second Avenue. Peter Hujar (American, 1934–1987). Self Portrait Jumping I, 1974. © 2022 The Peter Hujar Archive / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A fearless political firebrand, the radical artist David Wojnarowicz challenged the art world and lambasted America for failing the LGBT community, particularly in response to the AIDS crisis. Wojnarowicz’s art eschews a signature visual style but always contains his acid wit, burning rage, and transgressive politics.

Wojnarowicz met Hujar in 1980, and after a brief romance, the two settled into a platonic spiritual bond. Following Hujar’s death, Wojnarowicz moved into the loft so that he, according to his biographer, could “breathe the same air Hujar had breathed. He would hang on to any vestige.”

Wojnarowicz died, aged thirty-seven, in the Second Avenue loft on July 22, 1992. One week after his death, Wojnarowicz was given the first political funeral to come out of the AIDS epidemic. Written upon a huge banner that led the funeral procession beginning at the loft were the words: “DAVID WOJNAROWICZ, 1954–1992, DIED OF AIDS DUE TO GOVERNMENT NEGLECT.”

— George Benson, Consultant, NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

Left: Peter Hujar (American, 1934–1987). David Wojnarowicz with a Snake, 1981. Gelatin silver print, 14 3/4 x 14 5/8 in. (37.5 x 37.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2006, (2006.287). ©The Peter Hujar Archive, L.L.C. Right: David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954–1992). Untitled, 1984. Bone skull, papier-maché, barbed wire, battery, watch, and rusty nails, 10 × 6 3/4 × 13 1/2 in. (25.4 × 17.1 × 34.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Barbara and Eugene Schwartz, 1988 (1988.417.1a–e). © Estate of David Wojnarowicz

A well-connected photographer in downtown Manhattan’s avant-garde community, Peter Hujar moved into the loft at 181-189 Second Avenue in 1973 where he assembled a photography dark room. Wojnarowicz moved in after Hujar in 1987 and would also use the dark room to develop his own photography. The two artists shared a nuanced relationship that was imbued with mutual care and respect for one another. Both experienced similar childhoods and embraced the integrity of their creative output, in contrast to art-world or commercial success. When Peter Hujar passed away in 1987, Wojnarowicz lost a key figure in his personal and artistic life. He assembled an altar for Hujar in the loft and was deeply shaken by his death and absence. Today, Hujar and Wojnarowicz’s lives and work continue to signal an urgent demand for humanity for LGBTQIA+ communities. Both artists are remembered for their unwavering activism and outrage against anti-LGBT discourse and government neglect of the ongoing AIDS crisis.

— Alexis Gonzalez, Program Coordinator, Audience Development and Engagement, Education

Watch Gonzalez discuss Hujar and Wojnarowicz’s works outside of their shared loft with The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project on Instagram.

Martin Wong: Residence and Studio

141 Ridge Street, Lower East Side, Manhattan

Amanda Davis, NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, 2018

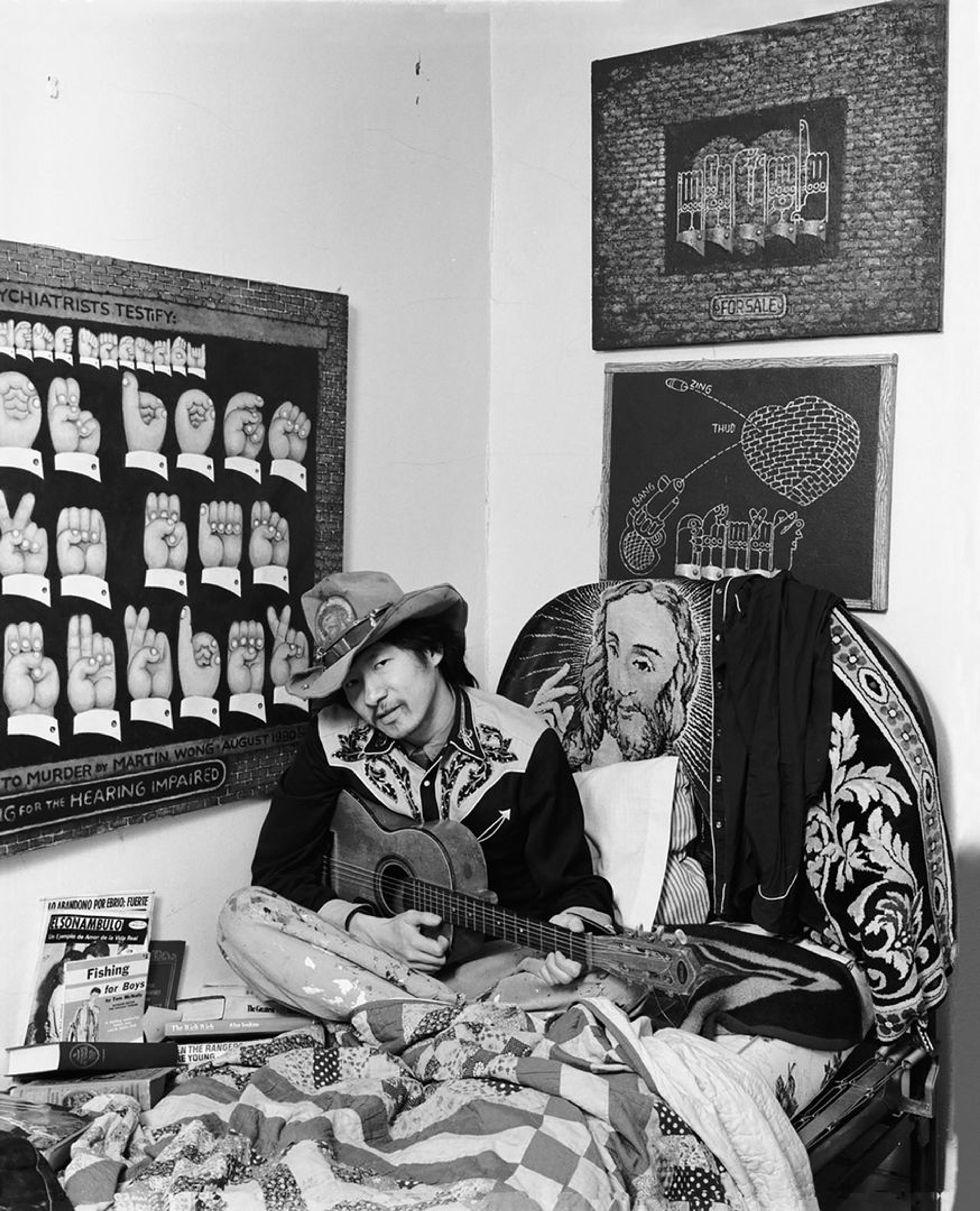

In 1982, openly gay artist Martin Wong (1946–1999) moved to 141 Ridge Street. According to the Martin Wong Foundation, Wong’s “uniquely representational imagery encompassed the urban environment, the history and stereotypes of Chinatown, and homoerotic content.”

Perhaps Wong’s most important friendship was with writer Miguel Piñero (1946–1988). Wong and Piñero were frequent artistic collaborators and were briefly lovers; for about one year, Piñero lived with Wong in the Ridge Street apartment. Wong’s first neighborhood scene was Attorney Street (Handball Court with Autobiographical Poem by Piñero) (1982–84).

During Wong’s time on Ridge Street, his paintings most often took inspiration from San Francisco’s Chinatown neighborhood, where he was raised, and Manhattan’s Lower East Side and Chinatown. Wong created a series of paintings that focused on the displacement of neighborhood residents in the face of gentrification. Brickwork and American Sign Language featured regularly in his work. Wong died of AIDS-related complications in 1999, at the age of fifty-three.

— NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

Martin Wong (American, 1946–1999). Attorney Street (Handball Court with Autobiographical Poem by Piñero), 1982–84. Oil on canvas, 42 in. × 54 1/4 in. (106.7 × 137.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edith C. Blum Fund, 1984 (1984.110) © The Estate of Martin Wong

Wong’s extraordinary painting Attorney Street resonates with the vibrant cacophony of multilingual New York. It commemorates the neighborhood in which he lived on Manhattan’s Lower East Side as well as the many layers of language that resounded throughout it. The work gains more meaning with the brilliant, autobiographical poem by the artist’s dear friend and erstwhile lover Miguel Piñero that Wong transcribed on its surface.

Born to Chinese American parents in San Francisco, Wong was involved in local radical queer performance troupes such as the Cockettes and the Angels of Light before he moved to New York in the late 1970s. While pursuing creative endeavors, he worked for a spell in The Met’s bookstore. By the time he met Piñero—a talented playwright, former convict, actor, and cofounder of the famous Nuyorican Poets Cafe—Wong was living in a walkup apartment on Ridge Street on the Lower East Side. The handball court not far away doubled as a canvas for a number of talented local taggers, and Piñero asked Wong to memorialize the newest addition, freshly painted by a handsome young friend, to its palimpsest of a wall.

Piñero composed his new poem expressly for the work, and Wong faithfully transcribed it before adding his own responsive epitaph at bottom, translated into his signature interpretation of American Sign Language’s finger-signed alphabet. Although the scene is devoid of people, the layers of language reverberate with the vibrancy of Loisaida—the Nuyorican name for the Lower East Side, Wong’s newly adopted home, a resilient community rich with a multiplicity of queer communities of color.

— Ian Alteveer, Aaron I. Fleischman Curator, Department of Modern and Contemporary Art

Watch Alteveer discuss how the Lower East Side influenced Wong’s painting with The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project on Instagram.

Martin Wong in 1985. Photo by Peter Belamy. Courtesy the Estate of Martin Wong and P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York

Through the works of these artists and writers, we can glimpse a city that no longer exists—and perhaps only existed for the few moments that the work was created. Yet these works remain painfully relevant, showing us beauty, hope, and anger in communities ravaged by pandemics, inequality, government indifference, and gentrification. The work of these artists was shaped by their LGBTQIA+ identities, from artistic partnerships borne of love affairs to the themes that dominated their art. These artists are part of an ongoing legacy of queer art in New York City that shapes our view of the city and of ourselves.