In Our Terribleness (Some Elements and Meaning in Black Style) (1970), a collaboration between radical poet Amiri Baraka and the photographer Billy Abernathy, remains a shining and resilient record of Black style. The book combines Abernathy’s stirringly elegant depictions of Chicago’s Black community in the 1970s with Baraka’s consciousness-raising poetry. Embedded within mirrored pages and jazz riffs in the poet’s verse is the majestic and powerful statement “everything’s for real.” It is an idea that I carry forward like the Akan people’s mythical bird Sankofa, a symbol for learning from the past to create the future. Everything’s for real—a mantra that serves as a call to action—now defines my understanding of style and my philosophy for design. What I aspire to create in its purest form is real on many levels: It is real because it means something; it is real because it comes from history; and it is for real because it is rooted in true style created by originators.

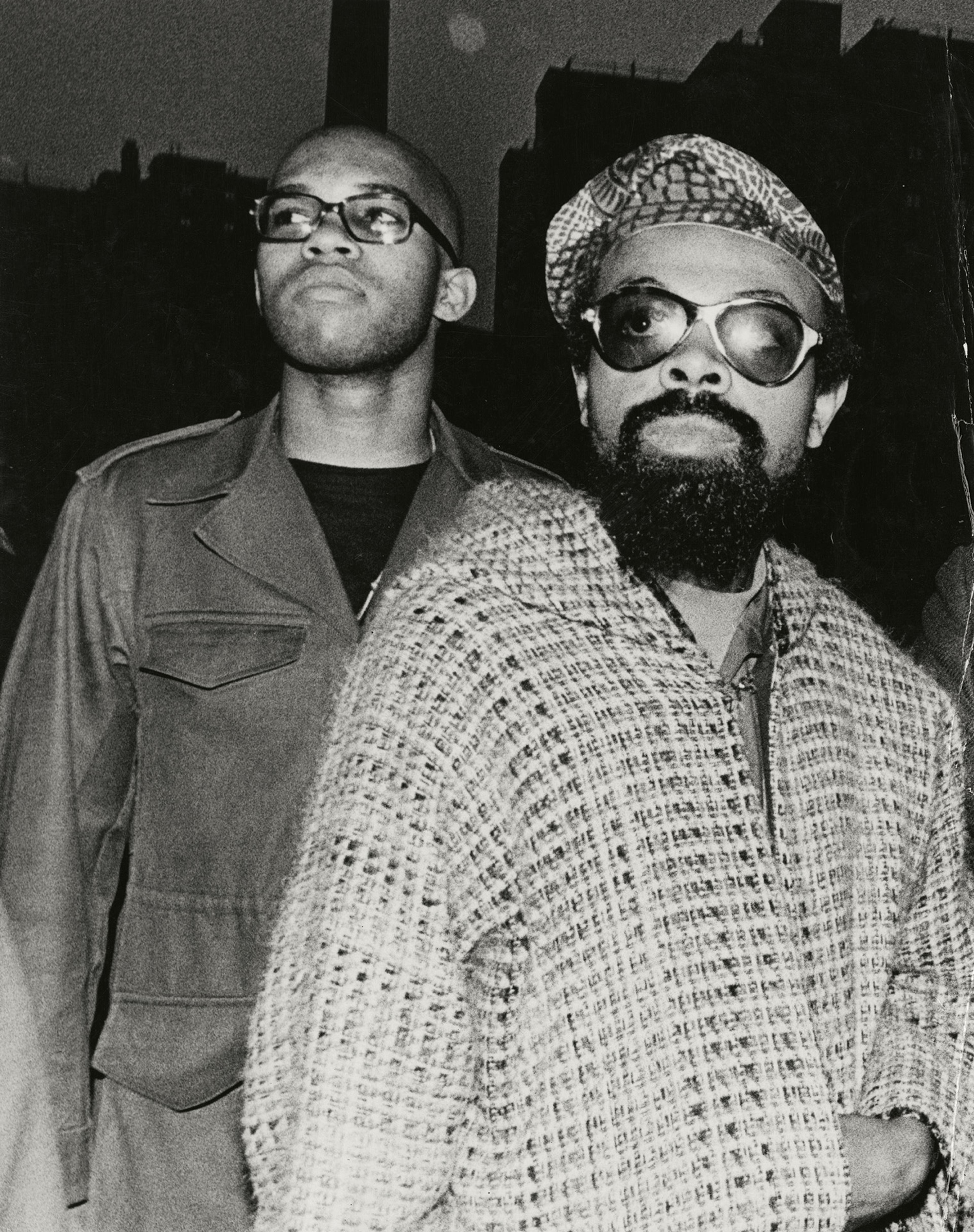

Amiri Baraka wearing sunglasses. Amiri Baraka Archives, Columbia University Library

My search for meaning in Black style began as a search through ancestry to reveal beauty and complexity over time and across traditions of expression. Some elements can be traced to what I experienced in my father’s study: early memories of his improvisation on the grand piano; the vast library celebrating Romantic poets, fine arts, and Caribbean poetry; the elegant militancy of a portrait of Malcolm X; and a grand poster of Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance, an exhibition curated by David A. Bailey at London’s Hayward Gallery in 1997.

Isaac Julien CBE RA (British, b. 1960). Pas de Deux No. 2 (Looking for Langston Vintage Series), 1989, printed 2016. Kodak Premier print, Diasec mounted on aluminum, 70 ¾ × 102¼ in. (179.7 × 259.7 cm). Credit TK

I elaborated on these early pillars, seeing the Harlem Renaissance come to life through the lens of Isaac Julien’s Looking for Langston (1989)—definitions of beauty, tenderness, and grace forever situated there. This tenderness also extends to how I look to connect with people through the clothing and images I create. Julien’s depiction of the character Beauty, in the finery of a tuxedo and draped in sheets, recalls the homoerotic visions of fashion photographer George Platt Lynes. Reminiscent gestures are reflected, too, in the strands of pearls and extended fingers of dancer Geoffrey Holder in flight and the elemental dress of James Baldwin—his regal jewelry, pastel-toned denim, and seductive brown leather.

The radical expression I observed in Baraka’s work is also defined by photographs of the Black Panthers and by blaxploitation films—namely, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971) by Melvin Van Peebles. I witnessed a rebel spirit in the jagged cool of the characters in Rockers (1978) and Beth Lesser’s dancehall photography. I feel a deep connection to a style that values heritage; there is something sweet in the appreciation of the crisp shirting and fine leather sandals that I saw worn by musicians Augustus Pablo and Bob Marley—but powerful, too, in their wearing of clothes with a presence and a dangerousness that created new glittering potential for future style. In the archive, I saw invention and evolution; righteous embodiment; artists in motion, resisting, forever creating fresh stylistic pathways for new generations alongside free and expansive ways of being. These individuals were for real, their style a mirror of who they were and a reflection of what they could offer the world.

I saw invention and evolution; righteous embodiment; artists in motion, resisting, forever creating fresh stylistic pathways for new generations alongside free and expansive ways of being.

The figure of the Black intellectual was an ever-present guide. New dreams were found in writers Ben Okri and Ishmael Reed, as well as Steve Cannon, publisher of the literary magazine A Gathering of the Tribes who always wore Ray Charles–style sunglasses on his face and glorious beads around his neck. David Hammons presides as the artist-as-shaman in talismanic cloth, his dress the reflection of a wondrous soul. Ishmael Reed once told me that clothing was as significant to Black cultural traditions as drumming. His 1972 masterpiece Mumbo Jumbo provided further inspiration to enjoy hybridity, historical irreverence, and play. Immaterial ideas like polyrhythm, time travel, and the spirit certainly could be other important elements to consider.

Through endless journeys that continue to unfold each day, I realize that I have been searching for Black princes. From the biblical Magi and seventeenth-century statesman Malik Ambar to André Leon Talley. I saw princes in the poignant characters of The Black House (1973–76) by photographer Colin Jones; they remained dignified, crafting beauty from the debris of their surroundings. Shining reflections of light.

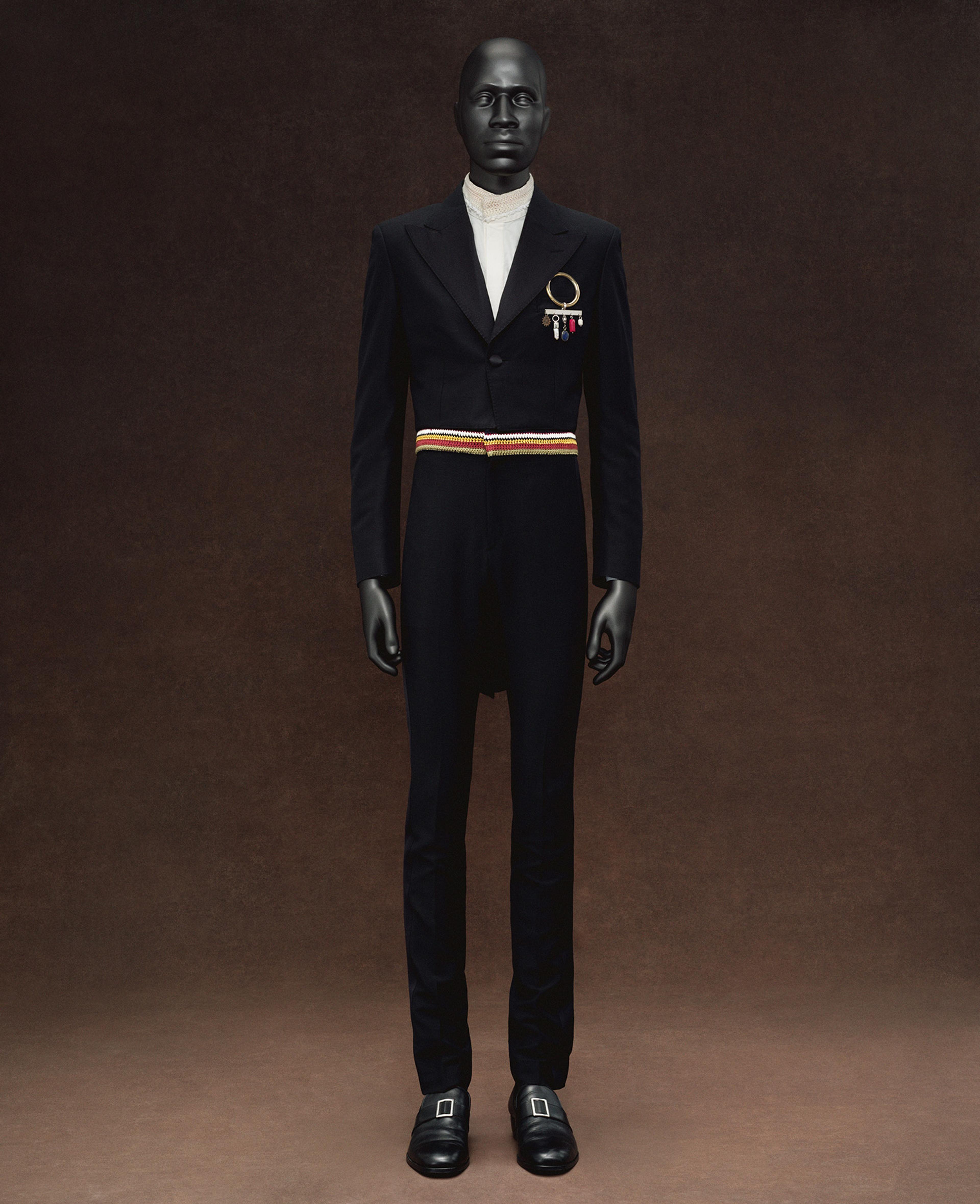

Wales Bonner (British, founded 2014). Grace Wales Bonner (British, b. 1990). Ensemble, spring/summer 2017. Tailcoat of black wool plain weave; trousers of black wool plain weave embroidered with polychrome cotton crocheted waistband and appliquéd black silk satin side stripes; shirt of ivory cotton plain weave embroidered with cotton crocheted collar; brooch of silver-plated brass, freshwater pearls, and beads of lapis lazuli. Courtesy Wales Bonner.

Tupac wore a crown of diamonds on his ring. Biggie wore the crown too. I always loved André Leon Talley’s appreciation for finery and the best the world could offer; he must have understood his majesty in Charvet shirts, velvet Manolo Blahnik shoes, and pastel alligator coats. I think about him often—his extraordinary clothes—as well as the role of a tailor creating something from nothing, weaving threads, conjuring magic. The best of Black style emanates from a soulfulness resounding in the way a person embodies clothing, bringing “invention into existence” (Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks)—like Jean-Michel barefoot in paint-splattered Armani pinstripes, sitting in his tenderness, waiting patiently for the crown. Boom, for real.

This essay is adapted from the catalogue Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, which accompanies an exhibition on view through October 26, 2025.