In conjunction with the exhibition Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, Idelle Taye, founder of Guzangs, reflects and expands upon the rich relationship between sartorial expression and ancestral legacies across the African continent through the work of seven trailblazing contemporary designers.

The Costume Institute’s current exhibition Superfine: Tailoring Black Style offers a sweeping exploration of the relationship between Black identity and sartorial expression. From polished tailoring to flamboyant flair, Superfine reframes dandyism not just as a fashion statement but as a subversive strategy—a method of resistance, invention, and visibility. To understand the full story of Black elegance, however, we must look further back to the African continent, where ceremonial dress, material culture, and sartorial codes have long signified authority, beauty, and belief.

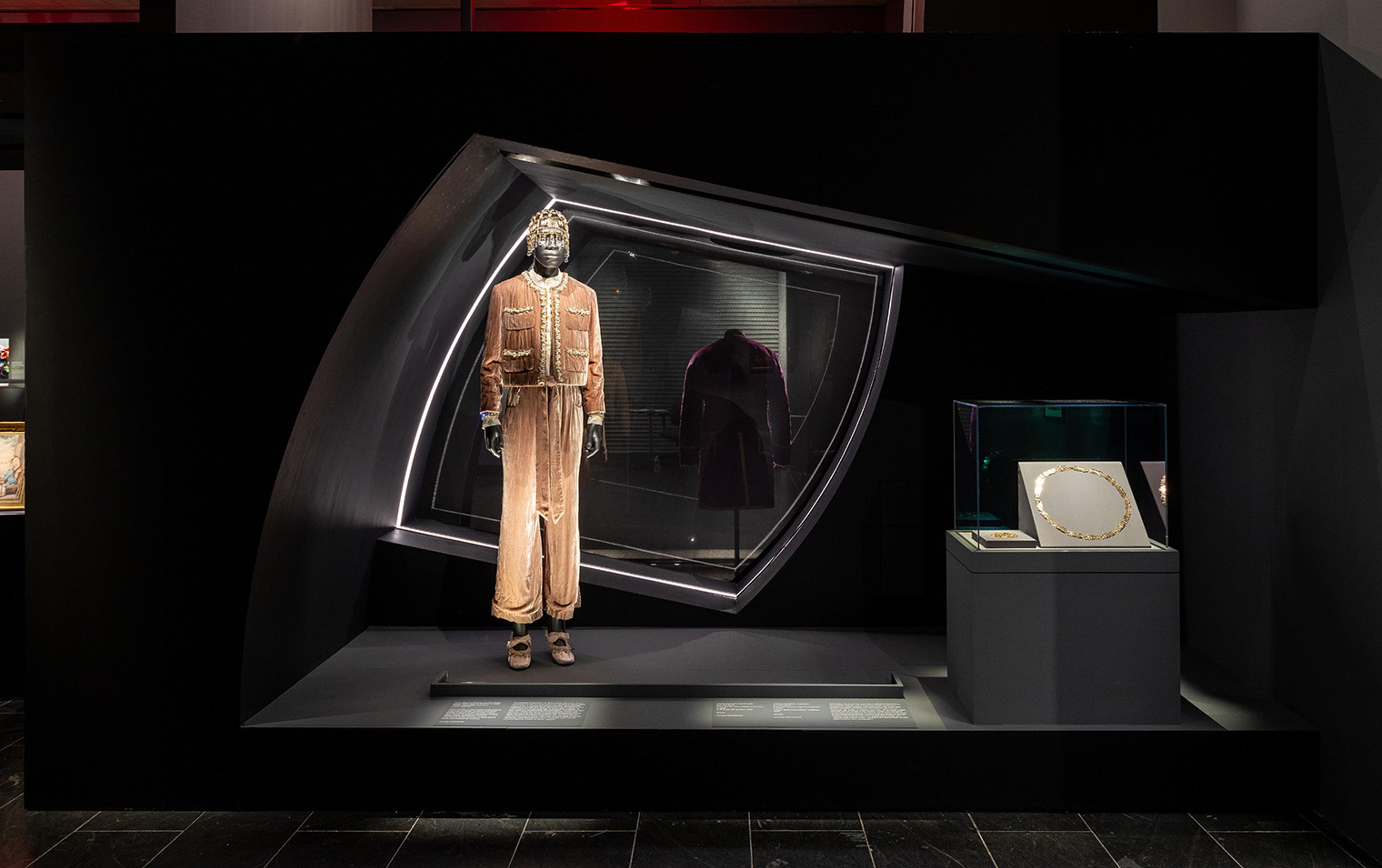

Gallery view in Superfine: Tailoring Black Style. Wales Bonner (British, founded 2014) Grace Wales Bonner (British, b. 1990) “Aime” ensemble, autumn/winter 2015–16. Courtesy Wales Bonner

This piece traces the threads between African dress traditions and the contemporary designers reshaping them today, from Maxivive’s defiant silhouettes to Lagos Space Programme’s decolonial construction and Wanda Lephoto’s spiritual tailoring. These designs are living narratives shaped by ancestral memory and cultural intent.

Tailoring as Cultural Speculation

Iké Udé (Nigerian American, b. 1964). Sartorial Anarchy #5, 2012. Pigment on satin paper, 54 × 36 in. (137.2 × 91.7 cm). NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale, Fla., Purchased with funds provided by Michael and Dianne Bienes, by exchange. Leila Heller Gallery

Superfine showcases how clothing has functioned as both armor and artifice. Take Iké Udé’s portrait in his Sartorial Anarchy series: a deliberate clash of Yoruba trousers, Zulu weaponry, and eighteenth-century European fashion. Here, self-styling becomes a deliberate act of world-building, dissolving borders of time, geography, and gender. The look is both theatrical and assertive, merging disparate codes into a cohesive visual manifesto of the modern dandy.

Maxivive (Nigerian, founded 2007). Papa Oyeyemi (Nigerian, b. 1992). “7562RJ” ensemble, 2025. Mixed textiles. Courtesy Maxivive. Photo by Kolade Oseni

This same approach characterizes the work of Papa Oyeyemi, founder of Nigerian brand Maxivive. Oyeyemi destabilizes expectations around masculinity through fashion that is fluid, sensual, and intentionally unsettling. His tailored pieces frequently play with volume, drape, and asymmetry, but beyond the silhouette lies a conceptual core: the right to self-definition. In a cultural context where binary gender norms dominate, Oyeyemi designs with defiance—drawing not from Eurocentric androgyny but from indigenous Yoruba philosophies that embrace multiplicity.

Maxivive also challenges colonial frameworks in other ways. Oyeyemi has abandoned the Western fashion calendar altogether, opting instead for seasons that reflect Nigeria’s climate: Harmattan, Wet, and so forth. These localized seasons shape not only the timing of his collections, but also their form—garments adapted for dusty winds, humidity, or shifting temperatures. It’s a recalibration of fashion to fit lived experience, not foreign tradition.

Lagos Space Programme (Nigerian, founded 2018). Adeju Thompson (Nigerian, b. 1991). Project 8 (AW24–25). Exploring transnational Black experience and the power of beauty as defense, 2024–25. Courtesy Lagos Space Programme

For Adeju Thompson, adire is more than a textile: it is testimony. Across several collections, including his recent Autumn/Winter 2024–25 show, Thompson repositions the indigo-dyed Yoruba cloth as a site of queerness, lineage, and futurity. His garments are designed for a postcolonial, post-binary figure—aristocratic yet subversive, fluid yet grounded—arriving at Ojude Oba, a Nigerian festival, as both guest and mirror. A high-waisted silk adire trouser might recall pageantry; a knit agbada fuses imperial tailoring with Yoruba symbolism. As Thompson puts it: “For me, clothing is a tool of cultural speculation—a place where I imagine new futures rooted in Yoruba philosophy, spiritual memory, and queer presence.”

Imane Ayissi (Cameroonian, b. 1969). Coat, spring/summer 2025 couture. Hand-dyed reversible cotton gabardine, crafted in Cameroon. Courtesy Imane Ayissi

Imane Ayissi’s couture collections similarly challenge fixed ideas of identity and dress. Drawing from his Cameroonian heritage and classical training in Paris, Ayissi merges silk brocade with kente, raffia with organza—an Afro-European fusion that resists reduction. His work reflects a careful negotiation between ancestral aesthetics and contemporary form, asserting that African fashion can be at once spiritual, sculptural, and global.

In Rwanda, Moshions (founded by Moses Turahirwa) fuses indigenous motifs with impeccable tailoring. The brand’s reinterpretation of ceremonial robes, woven mesh capes, and embroidered sashes underscores a deep respect for both cultural specificity and evolving masculinities. Turahirwa’s designs are less about fashion as spectacle and more about fashion as a grounding force: a tactile language of place, history, and self-assertion.

South African designer Wanda Lephoto’s Black Renaissance collection delves into South African dress histories shaped by British imperialism and resistance movements. A standout piece is a khaki biker jacket inspired by the Zion Christian Church (ZCC) uniform, worn by Lephoto’s father. Traditionally rooted in colonial British military attire, the ZCC uniform is a symbol of religious order and discipline. Lephoto reimagines it with flower appliqué, a split green-and-khaki trouser, and softened tailoring—a deliberate shift from rigidity to personal storytelling. In doing so, he transforms a garment of conformity into one of remembrance and critique. His collection doesn’t erase the complexities of South African dress history; it retells them with tenderness and defiance.

Material as Memory

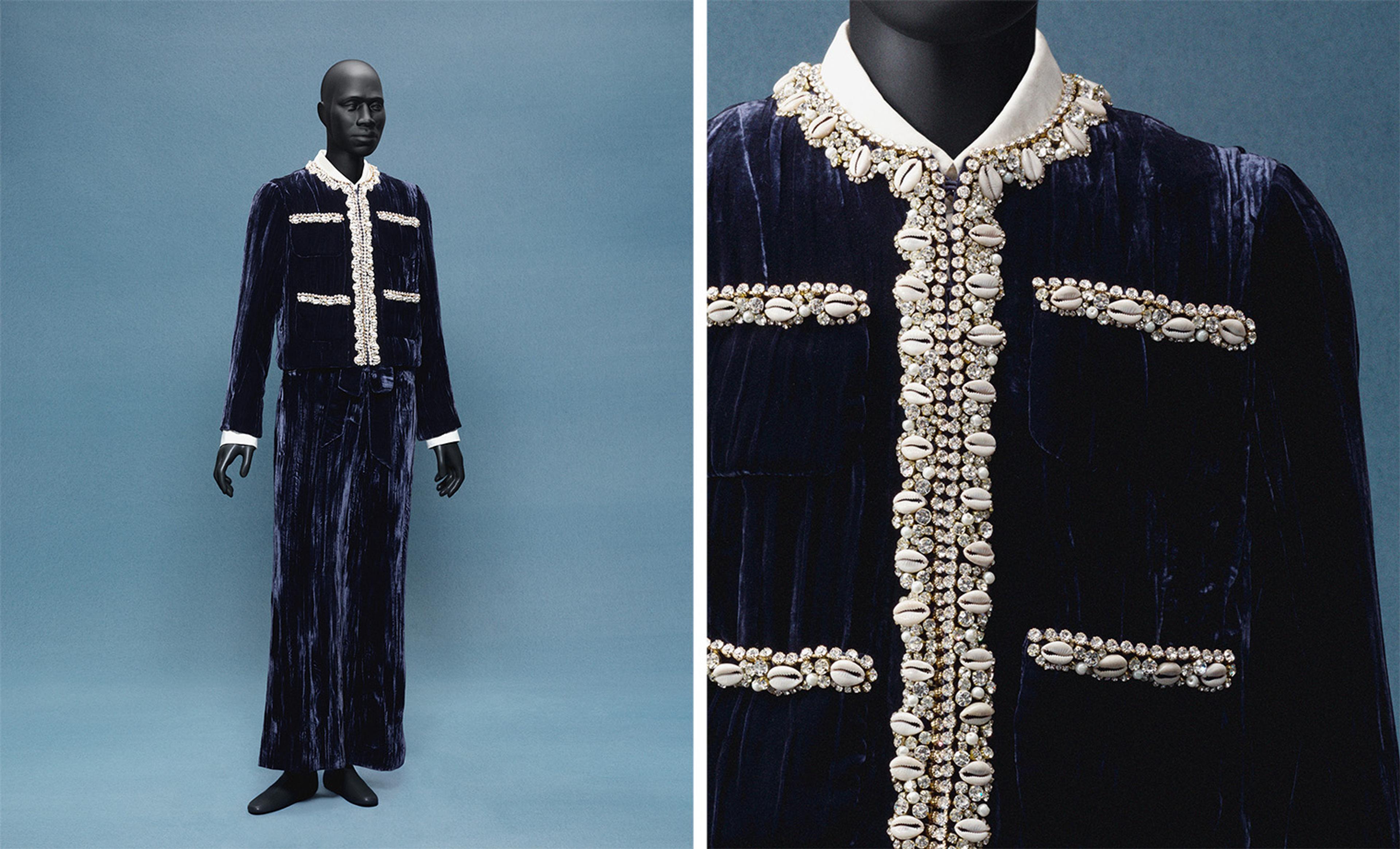

Wales Bonner (British, founded 2014). Grace Wales Bonner (British, b. 1990). "Aime" ensemble, autumn/winter 2015–16. Jacket of blue silk crushed velvet embroidered with cowrie shells, clear and yellow crystals, and ivory glass pearls; trousers of blue silk crushed velvet; shirt of white sand-washed silk plain weave. Courtesy Wales Bonner

African textiles and embellishments are not merely ornamental—they are epistemologies in cloth. Throughout the continent, what you wear tells who you are: your lineage, your region, and your role in the community.

Grace Wales Bonner’s opulent “Aime” ensemble, on display at The Met, captures this idea. The velvet suit is encrusted with cowrie shells, historically used as currency across West Africa and revered as symbols of wealth, femininity, and divine protection. Rather than mimic the sharp lines of Savile Row, Wales Bonner swathes her model in an abundance of meaning, letting African semiotics recast the codes of Western luxury.

Wanda Lephoto (South African, b. 1993). Ensemble, autumn/winter 2021–22. Blazer styled with traditional iBeshu flap. Courtesy Wanda Lephoto

Wanda Lephoto, meanwhile, interrogates colonial legacies while constructing new narratives. Informed by traditions like the Shembe Church and the social realities of postapartheid Johannesburg, Lephoto’s designs often stage a “cultural fusion”: the deliberate blending of formal and traditional codes. A sharp blazer is paired with a customary iBeshu flap; a church shirt recast with sacred embroidery. These juxtapositions craft new propositions for identity and representation, especially for those historically excluded from fashion. Lephoto’s silhouettes carry both precision and spirit, anchored in the belief that tailoring can be a vessel for healing, storytelling, and social imagination.

This sense of local rootedness also resonates with many North and East African traditions. In Ethiopia, for example, the ceremonial shamma robe worn during Orthodox Christian rites is layered, hand-woven, and adorned with symbolic striping. These garments are not simply beautiful: they are portals into spiritual and communal identity. Such ceremonial codes echo in the work of Ethiopian designer Yonael Marga, whose Chereka collection reimagines traditional Ethiopian dress through a forward-looking, speculative lens. Drawing from the adornment practices of the Oromo and Tigray peoples and the symbolic language of royal regalia, Marga’s work honors ritual while envisioning new aesthetic futures.

A Global Conversation, Rooted at Home

House of Balmain (French, founded 1945). Olivier Rousteing (French, b. 1985). Belt, autumn/winter 2024–25. Gold-colored brass and black enamel. Courtesy Balmain

“Bouquet” is a sculptural belt created by Olivier Rousteing for Balmain. Made of molded brass, interlocking hands cradle a bouquet—a direct reference to Ghanaian artist Prince Gyasi’s 2021 image Valeurs. The structure of the hands introduces a message of kinship and affection. Rousteing renders Gyasi's image in three dimensions, translating the photograph’s emotional and cultural weight into wearable form. Together, they blur the line between garment and sculpture, gesture and message—bridging photography, design, and Black identity on a global stage.

LOUIS VUITTON (French, founded 1854). Virgil Abloh (American, 1980–2021). Ensemble, autumn/ winter 2021–22 menswear. Jacket and trousers of cream polyester-wool barathea; shirt and tie of white cotton poplin; blanket of black and gray polyester-cotton-wool jacquard with allover kente-style LV monogram and geometric motif; airplane brooch of silver metal. Courtesy Collection LOUIS VUITTON

Virgil Abloh’s Louis Vuitton suit in the exhibition draws inspiration from kente cloth, a Ghanaian textile historically reserved for royalty and sacred ceremonies. While the textile is adapted for Western dress, its visual vocabulary remains distinctly African. The fabric is a reminder that prestige has long existed on the continent and is conveyed through stately pageantry, traditional ceremonial dress, and the distinctive codes present in textiles like bark cloth and kente.

What unites the work of Wales Bonner, Rousteing, Abloh, Maxivive, Thompson, Ayissi, Lephoto, Moshions, and many others is a shared commitment to cultural authorship. These designers are not trying to fit into fashion’s historical canon; they’re remaking it with their own language, materials, and intent. And now, institutions like The Met are beginning to reflect this shift. Superfine contributes to a broader effort to move beyond Western-centered narratives and foreground the long-standing, radically innovative contributions of African and diasporic creators.

These designers are not trying to fit into fashion’s historical canon; they’re remaking it with their own language, materials, and intent.

At a time when global fashion looks to Africa for inspiration, these designers remind us that inspiration alone is not enough. To truly engage with African fashion is to understand its histories, honor its makers, and amplify its philosophies. Because tailoring Black style is not merely a matter of construction—it’s an act of memory and authorship, care and clarity, and the refusal to conform from the outside in.

As the world continues to reckon with the legacies of race, colonialism, and representation, African designers are offering something else entirely: garments that recall ancestors, carry cultural weight, and propose freer futures. Thanks to this new generation of makers, the dream keeps expanding, stitched with purpose, cut with defiance, and worn with pride.