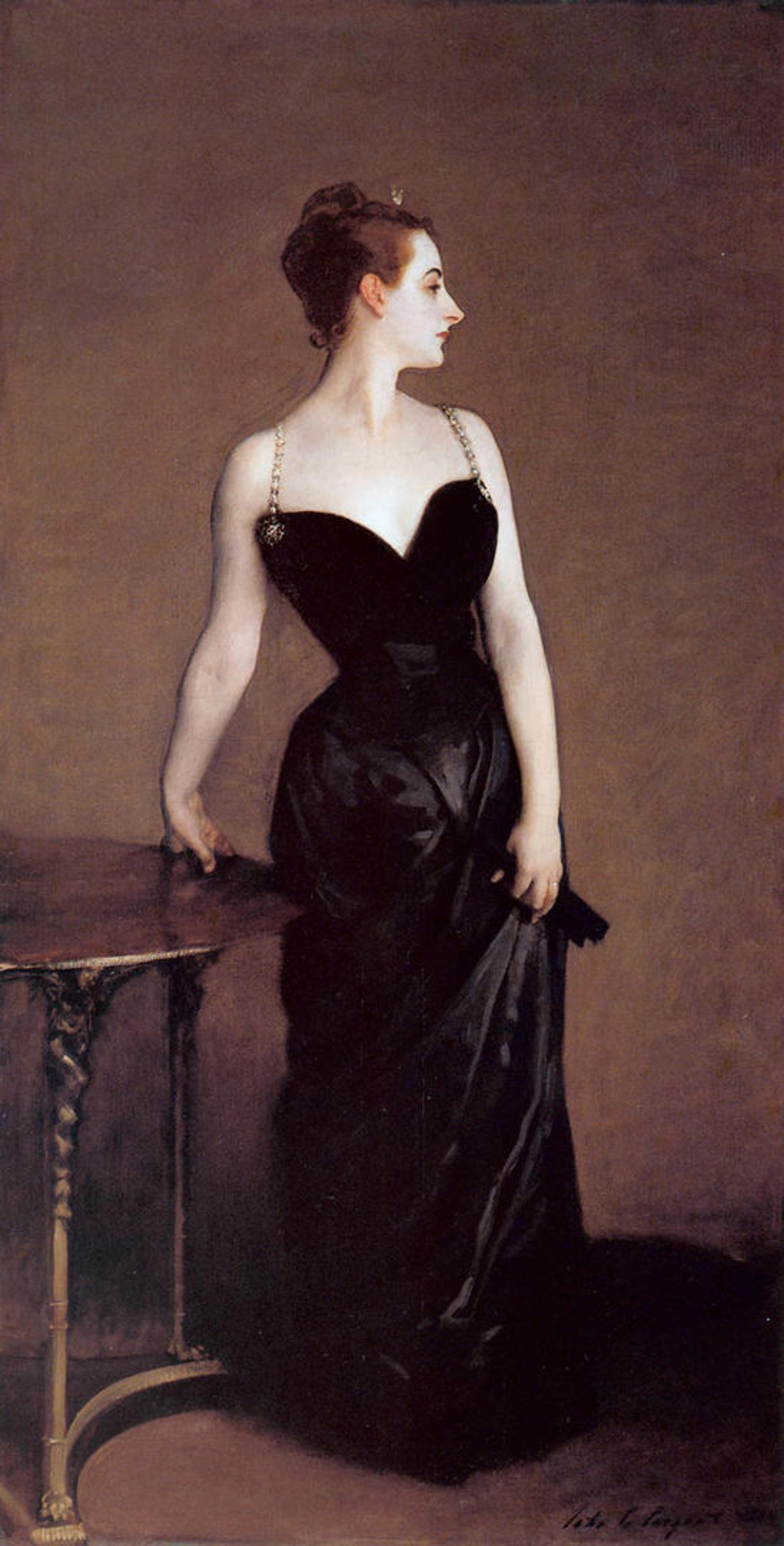

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Madame X (Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau), 1883–84. Oil on canvas, 82 1/8 x 43 1/4 in. (208.6 x 109.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1916 (16.53)

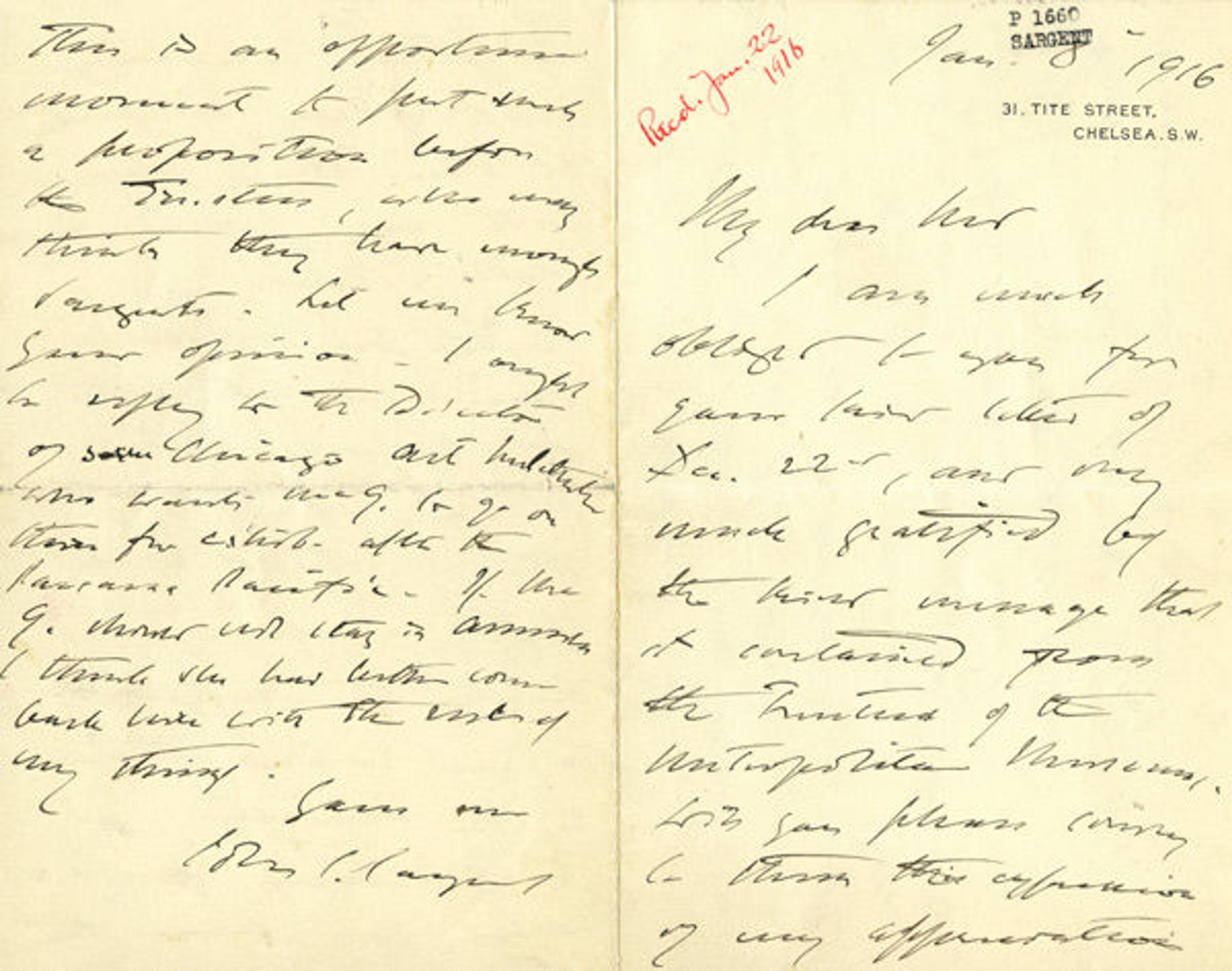

One hundred years ago today, on January 8, 1916, John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) offered to sell his masterpiece Madame X to The Met. Writing from his home in London to his longtime friend and Met Director Edward “Ned” Robinson, Sargent explained, “my portrait of Mme. Gautreau is now . . . at the San Francisco exhibition, and now that it is in America I rather feel inclined to let it stay there if a Museum should want it. I suppose it is the best thing I have done. I would let the Metropolitan Museum have it for £1,000.”[1] In honor of this anniversary, I revisited the correspondence between Sargent and Robinson in the Museum’s Archives with the assistance of James Moske, The Met’s managing archivist.

Sargent’s letter to former Director Ned Robinson, January 8, 1916.[2] The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives

Painted more than thirty years earlier, the iconic portrait of Virginie Avegno Gautreau (1859–1915), the American-born wife of a French banker, had nearly sidelined Sargent's career. In 1883, Sargent, a rising star in the Paris art world, convinced Gautreau to pose for him with the intention of creating a masterpiece to exhibit at the Paris Salon. When the portrait was displayed there in 1884, Sargent hoped it would lead to critical recognition and portrait commissions. Instead, it created an uproar that may have influenced Sargent’s decision to move to London for the rest of his life.

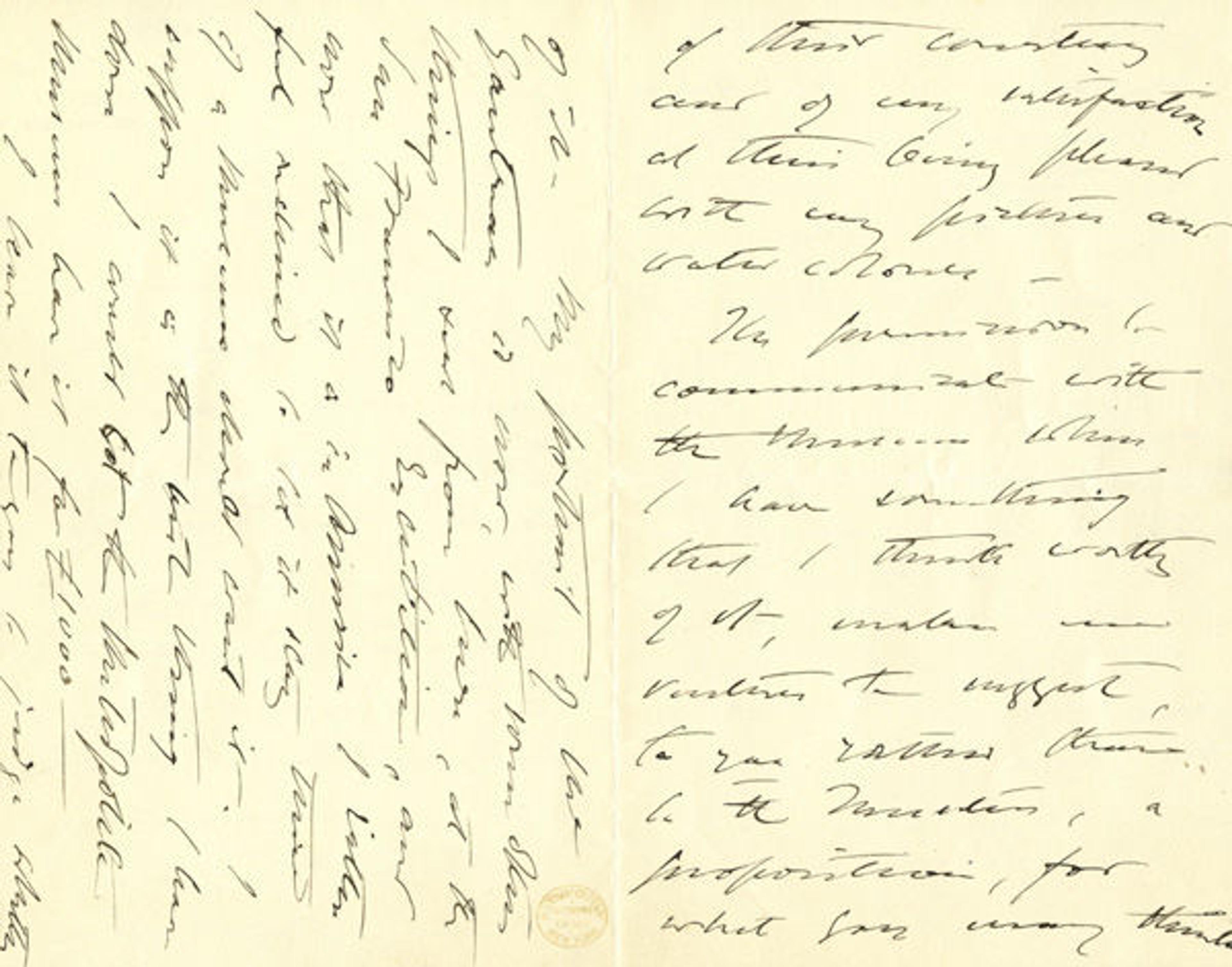

Many who saw the portrait were shocked by Gautreau’s haughty demeanor, provocative dress, and the dramatic artificiality of her cosmetics. In addition to displaying her daringly bare shoulders and plunging décolleté, Sargent originally painted her right, jeweled strap sliding off of her shoulder. Perhaps what astounded viewers the most was that the ambitious, young Sargent had boldly portrayed a new brazen “type” in Parisian society: the so-called professional beauty, a woman who audaciously used her appearance to gain celebrity and advance her social standing.

Madame X before her shoulder strap was repainted.

Though Gautreau had been complicit in the creation of the portrait, she, like Sargent, was devastated by the response. She (and her mother) begged Sargent to remove the painting from the exhibition. He flatly refused, claiming he had only depicted her as she appeared. At the close of the Salon, he repainted her shoulder strap and kept the painting in his studio, declining to exhibit or display it publicly for more than twenty years. By the late 1890s, when Sargent was widely recognized as one of the leading portrait painters of his generation in Europe and America, the portrait began to lose its tarnish—perhaps becoming even more appealing because of the scandal.

In 1905, Sargent began to exhibit the portrait again, first at the Carfax Gallery in London, and then at a handful of other exhibitions: London in 1908, Berlin in 1909, and Rome in 1911. In 1915, Sargent sent the portrait of Gautreau across the Atlantic to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, and was determined to find a home for it in the United States.

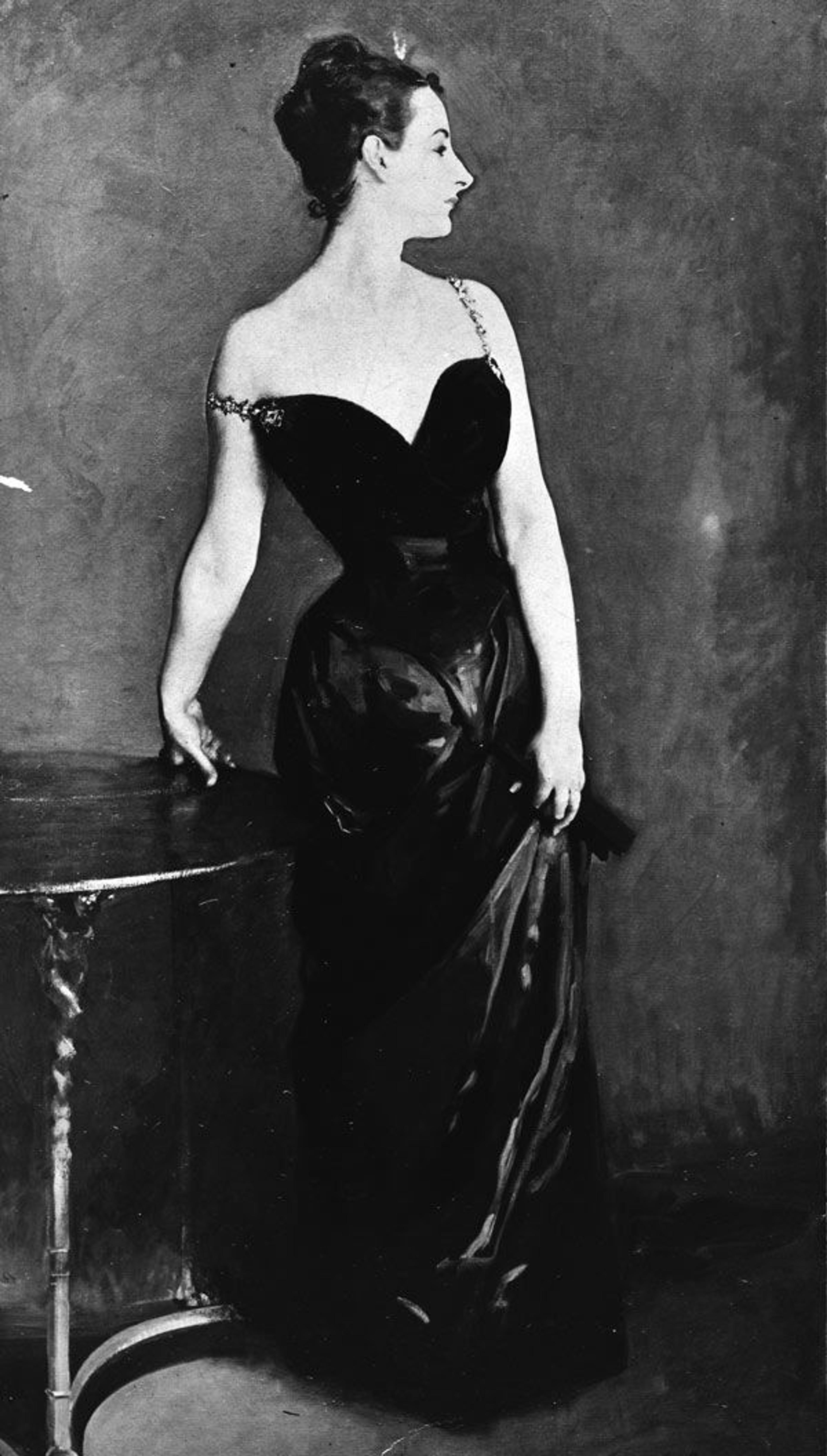

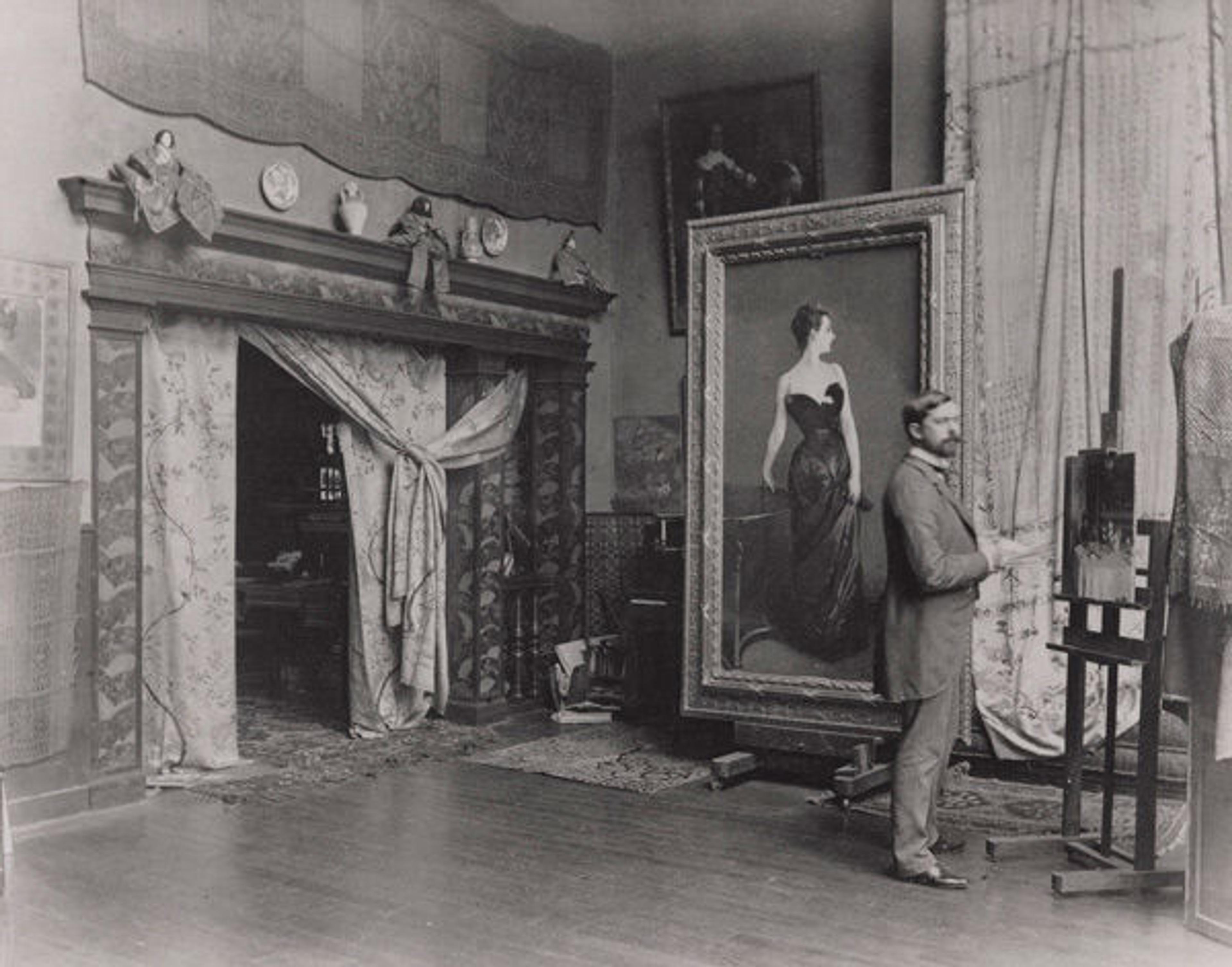

Sargent in his studio with Madame X, ca. 1885. © Private Collection

What prompted Sargent to sell the painting to The Met after three decades? Gautreau’s death in 1915 and Sargent’s desire to firmly establish his reputation in the United States. It’s not surprising that Sargent, who considered the portrait “the best thing I've done,” would be eager to place it in the nation’s preeminent public collection. Fortunately, Sargent had befriended The Met’s former Director Ned Robinson in the early 1890s, when Robinson was a curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Sargent was painting murals for that city’s public library.

Robinson came to The Met as assistant director in 1905 before being appointed director in 1910. During Robinson’s tenure, The Met benefitted greatly from his admiration of Sargent. Robinson actively pursued works by Sargent for the collection—purchasing several oil paintings and ten watercolors from him, and, later, bequeathing his own portrait by Sargent to the Museum.

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Edward Robinson, 1903. Oil on canvas; 56 1/2 x 36 1/4 in. (143.5 x 92.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Edward Robinson, 1931 (31.60)

After receiving Sargent’s offer of Madame X on January 22, 1916, Robinson wrote to the Museum’s Committee on Purchases and explained, “I have tried in vain for years to get this picture from him . . . but for personal reasons he has always refused to part with it, and his change of decision therefore comes as a complete surprise.” Robinson was thrilled at the opportunity and what he recognized as a “moderate” price.

Six days after receiving Sargent’s letter, the committee approved the purchase and Robinson telegrammed Sargent, “Museum takes Gautreau portrait at price named with thanks for opportunity.” In response, Sargent suggested, “I should prefer, on account of the row I had with the lady years ago, that this picture should not be called by her name.” In the formal paperwork, she assumed her title, Madame X.

When she was installed in the in The Met’s galleries, the New York Herald celebrated her arrival with the headline, “Sargent Masterpiece Rejected by Subject Now Acquired by Museum” (News Clippings Scrapbook, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives). One hundred years later, her mysterious beauty continues to captivate visitors to The Met’s American Wing, and her evocative title reminds us of the scandal.

Notes

[1] In 1916, £1,000 equaled about $4,770 (approximately $300,000 in 2026 dollars). Measuring Worth, 2026.

[2] Transcription of the full letter:

Jan. 8, 1916

My dear Ned

I am much obliged to you for your last letter of Dec. 22nd, and very much gratified by the kind message that it contained from the Trustees of the Metropolitan Museum. Will you please convey to them this expression of my appreciation of their courtesy and of my satisfaction at their being pleased with my pictures and water colours.

The permission to communicate with the Museum when I have something that I think worthy of it, makes me venture to suggest to you rather than to the Trustees, a proposition for what you may think of it. My portrait of Mme. Gautreau is now, with some other things I sent from here, at the San Francisco Exhibition, and now that it is in America I rather feel inclined to let it stay there if a Museum should want it. I suppose it is the best thing I have done. I would let the Metropolitan Museum have it for £1,000. I leave it to you to judge whether this is an opportune moment to put such a proposition before the Trustees, who may think they have enough Sargents. Let me know your opinion. I ought to reply to the Director of the Chicago Art Institute who wants Mme. G. to go on there for exhibition after the Panama Pacific. If Mme. G. should not stay in America I think she had better come back here with the rest of my things.

Yours ever

John S. Sargent