Standing at the top of a rocky hill, overlooking the Hudson River in Fort Tryon Park, The Met Cloisters has served as a beloved satellite location of The Metropolitan Museum of Art since 1938. Dedicated to medieval European art, the building integrates architectural fragments in spaces that evoke their original settings. Decades before The Met Cloisters was established, however, most of these elements were part of a very different medieval museum in northern Manhattan: George Grey Barnard’s Cloisters.

Contemporary view of The Met Cloisters.

Barnard's Cloisters opened in 1914 and operated until 1925, when their contents were sold to The Met. In 2025, current Met Cloisters staff are marking the centennial of this landmark acquisition by revisiting the story of George Grey Barnard, the first museum director, and the many medieval artworks he brought to the United States.

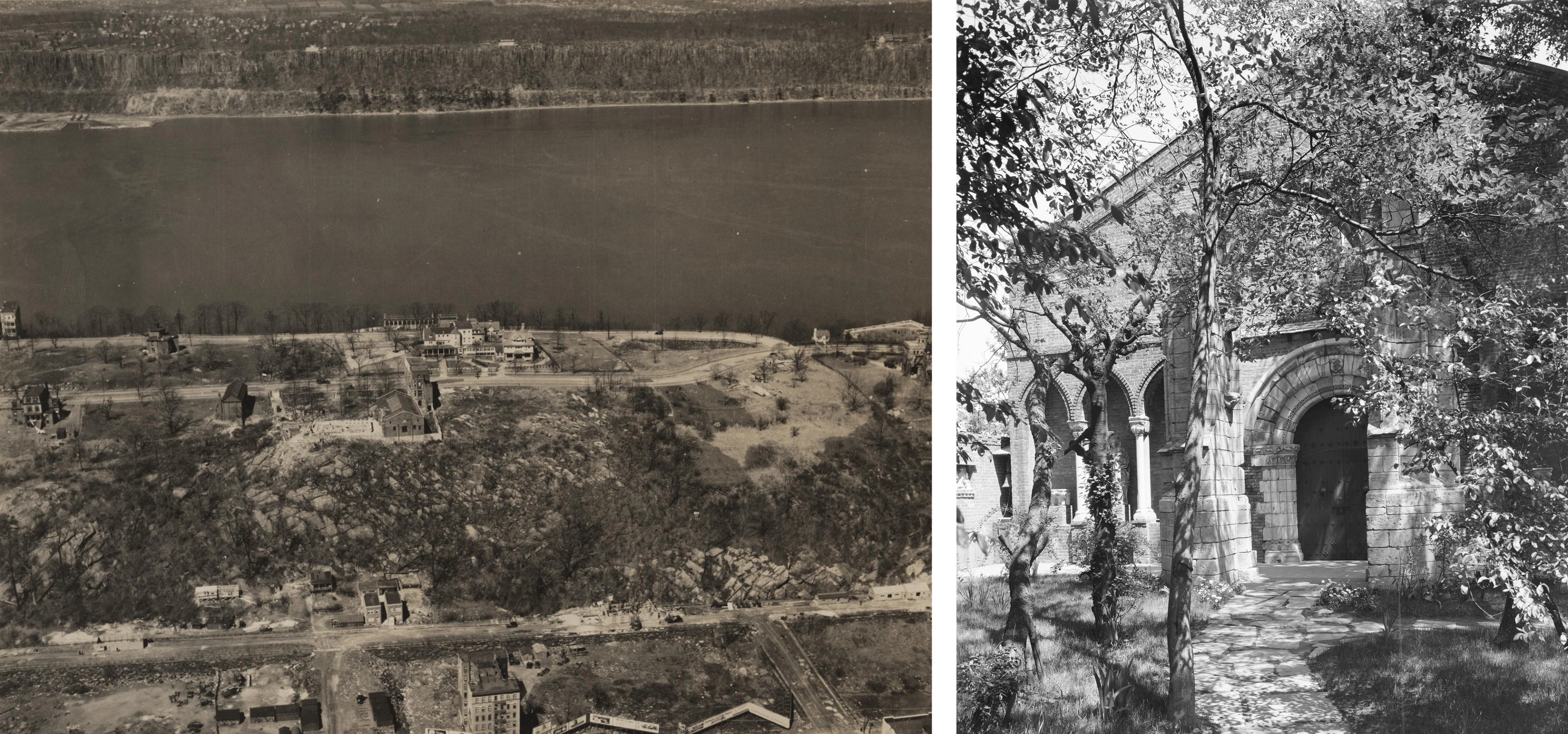

Photograph of George Barnard’s Cloisters from 1925.

Barnard’s career coincided with an unparalleled historical moment in which large amounts of medieval architectural sculptures, recently displaced from their sites of origin, were available for sale, and few laws regulated the export of national heritage. This created a unique opportunity to buy portions of medieval buildings, which were desirable for their ability to evoke the settings of the past. It also marks the beginning of America’s fascination with the arts of medieval Europe. Currently, an installation running through the end of December, titled The Met Cloisters 1925/2025, offers an opportunity to reconsider objects and archival materials related to Barnard’s museum.

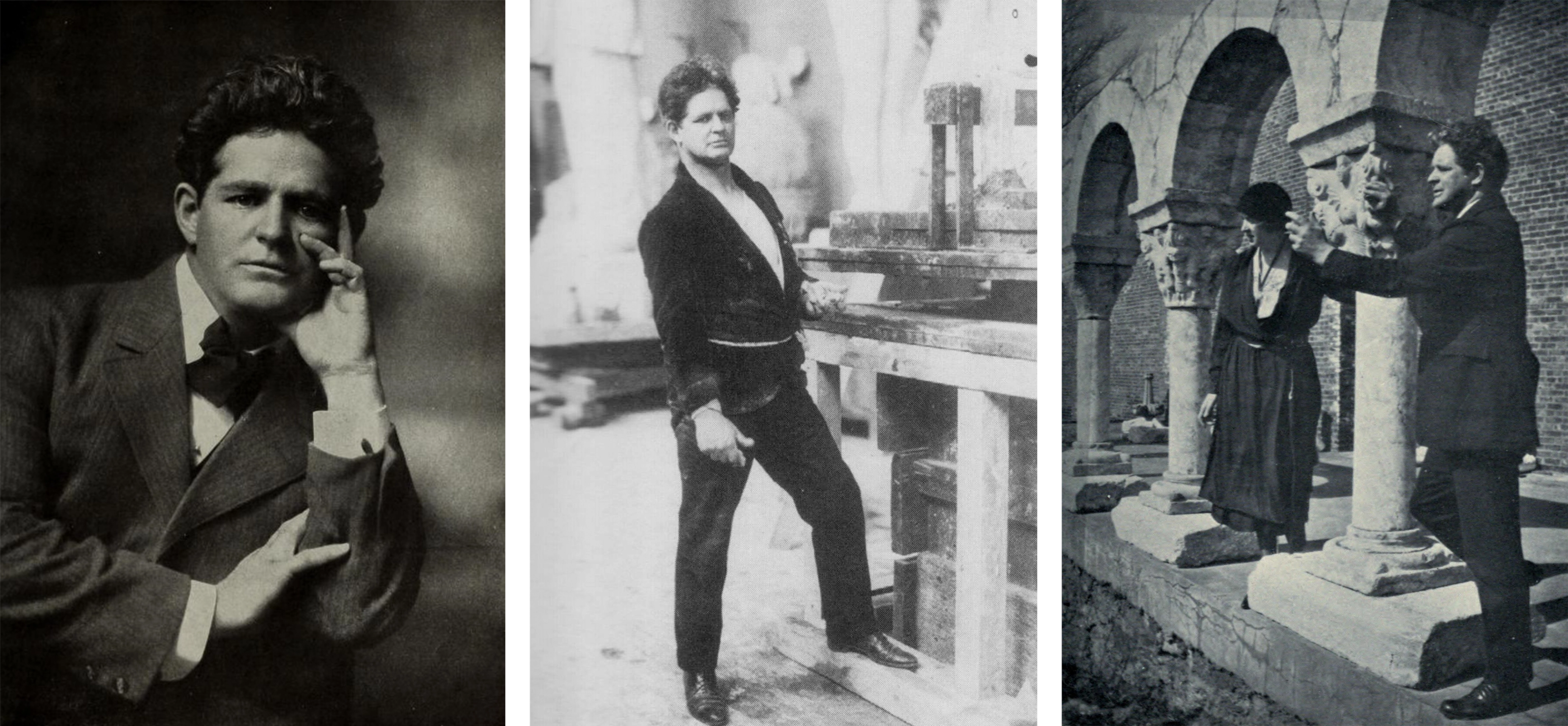

Left: Portrait of George Grey Barnard in 1908. Courtesy The World’s Work, 1909. Center: George Grey Barnard circa 1900. Courtesy Wikimedia. Right: George Grey Barnard and Clare Frewen Sheridan at his Cloisters. Courtesy My American Diary, ca. 1922.

George Grey Barnard (1863–1938) was an artist, collector, and entrepreneur. A successful sculptor in his own time, his monumental The Struggle of the Two Natures in Man (1888) was acquired by The Met in 1896, and he was commissioned to create façade sculptures for the Pennsylvania State Capitol in Harrisburg in 1902. While his own work was most closely inspired by the French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840–1917), Barnard was also drawn to the art of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries in an era when few appreciated its significance.

Barnard’s first opportunity to travel to Europe came at the age of twenty, when proceeds from an early commission allowed him to attend art school in Paris. Later, he returned to France, where he lived and traveled between 1906 and 1913. It was at this point that he began purchasing medieval art, assembling an extensive collection of mostly French and Spanish works, dating from 1100 to 1500. At the end of this period, he moved the entire collection, comprising hundreds of medieval artworks, to New York.

Aerial and exterior shots of Barnard’s Cloisters.

In 1914, on the same plot of land that contained his home and his studio, Barnard's Cloisters were opened. Its address at 700 Fort Washington Avenue is just half a mile south of the current site of The Met Cloisters, near the entrance to today’s Fort Tryon Park in Washington Heights. The area was one of the last parts of Manhattan to be fully developed in the early twentieth century.

Barnard’s reasons for creating this museum were complex. Despite his own enthusiasm for the material, clearly expressed in letters and diaries, his intent as a collector was always to exhibit and eventually sell these works to finance his own studio. Though he saw the artworks as an investment and needed a return on his money, he appreciated their educational value and sought a solution that would keep his collection in the public eye. Even as Barnard's Cloisters successfully drew many visitors, Barnard never ceased scouting for potential buyers. In the early 1920s, he finally caught the interest of curators at The Met. Crucially, the project also attracted the attention of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (1874–1960), a wealthy and well-educated financier, collector, and philanthropist.

Left: Photograph of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Right: Postcard of Barnard’s Cloisters.

The public-minded Rockefeller, who had admired the landscape of Manhattan’s rocky northern edge since childhood, had already begun purchasing the properties that would become Fort Tryon Park. In 1925, he agreed to unite his interests with The Met’s, generously funding the acquisition of Barnard’s collection and eventually financing the relocation of key pieces to the new park—creating The Met Cloisters as it exists today.

Dismantling Barnard’s Cloisters and designing a new museum did not happen overnight. The Met continued to operate Barnard's space for several years before its closure. Joseph Breck (1885–1933), the first Met Cloisters curator and director, made several modifications during this early phase, notably planting medieval-inspired gardens and completing the installation of additional cloister elements from Saint-Michel de Cuxa outside the building.

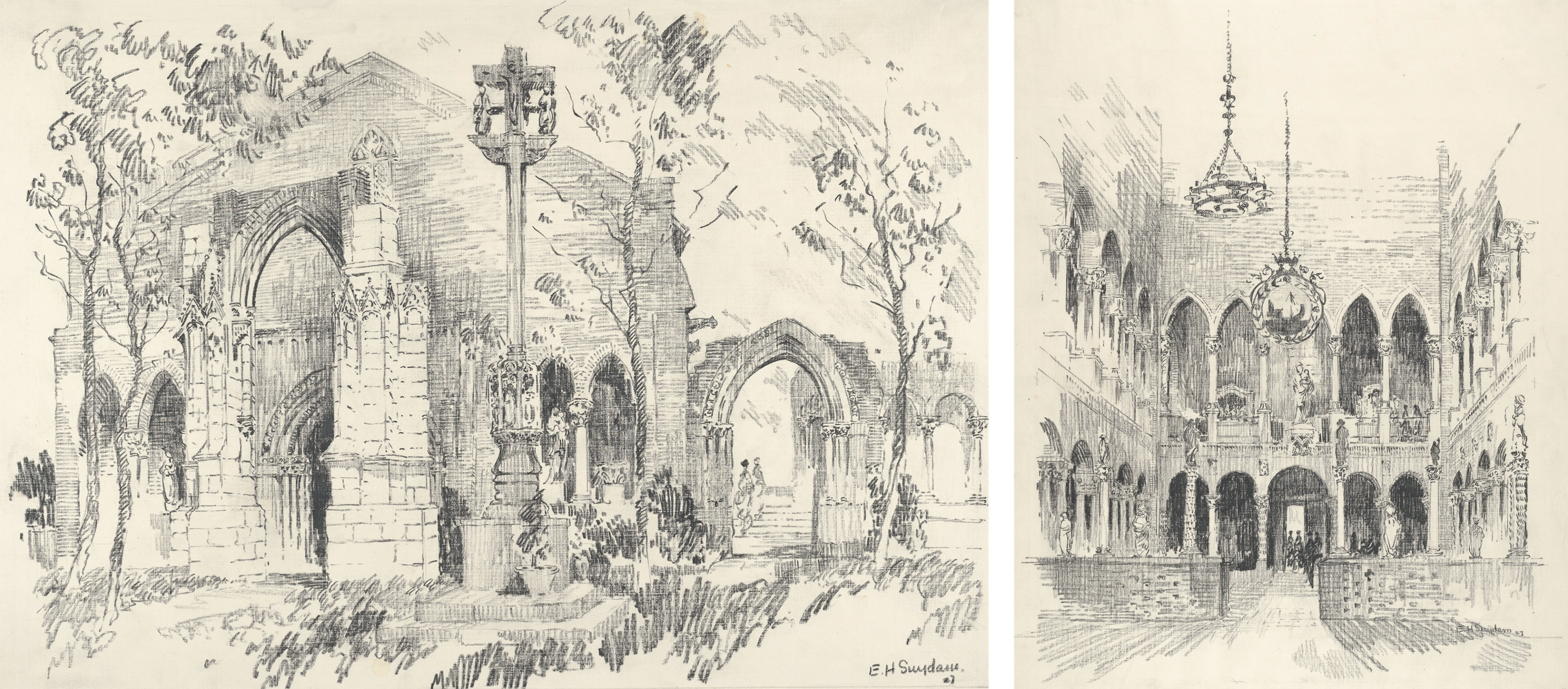

Left: Edward Howard Suydam (American, 1885–1940). Exterior View of the Entrance of Barnard's Cloisters, 1927. Charcoal, 11 5/8 × 15 5/8 in. (29.5 × 39.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museum Accession (X.317.4). Right: Edward Howard Suydam (American, 1885–1940). Interior View of the Nave of Barnard's Cloisters, 1927. Charcoal, 16 3/8 × 11 3/4 in. (41.5 × 29.7 cm) [unevenly cut]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museum Accession (x.317.1)

Meanwhile, visitors continued flocking to see the collection. Many were artists themselves, such as Edward Howard Suydam (1885–1940), an American illustrator who captured Barnard's Cloisters in a series of charcoal drawings in 1927. Suydam’s sketches limit the presence of visitors to subtle silhouettes in the background, focusing instead on the architectural fragments arranged in largely empty spaces. This solitary presentation likened The Met Cloisters to an ancient ruin, a vision in line with Barnard’s own romantic tendencies.

Barnard’s Cloisters illuminated by candlelight.

Barnard was surely aware that the dreamlike setting of The Met Cloisters was central to its appeal. He enhanced this theatrical aura by playing monastic chant on a gramophone, dressing the guards as monks, and illuminating the galleries with candlelight. Visitors wrote letters to Barnard, praising the experience as much as they lauded the collection. Though The Met would steer its outpost toward greater restraint in its later iteration, the spectacle of the original site was kept alive during its final years.

Perhaps it was in this spirit that early filmmakers drew inspiration from The Met Cloisters. The Hidden Talisman (1928), a short silent film produced by The Met, told a medieval ghost story in the evocative galleries, using special effects to create a phantasmal atmosphere. The film offers the most extensive surviving “virtual tour” of Barnard’s Cloisters, and its cinematography makes clear the endeavor was a kind of set piece from the start, ideal for staging performances. Indeed, the building was a host to many theatrical and musical shows; though little is known about these events today, we can guess that they were enhanced by the evocative setting.

Interior shots of Barnard’s Cloisters.

Designed to delight and engage those curious about the Middle Ages, the space itself—part chapel, part museum—was a remarkable achievement for a single enterprising person. Laid out as a large brick structure (newly built but artificially weathered to suggest antiquity), the interior loosely evoked the atmosphere of a church. Its central atrium was illuminated by skylights, framed by arcaded aisles, and crowned with an apse at the east end. Though modern, the architecture incorporated many medieval elements. Barnard’s arrangements of these fragments resulted from his own vision, rather than a desire to reconstruct their original functions faithfully.

Interior of Barnard’s Cloisters showing a staircase with multiple works in his collection.

Particularly high-quality artworks were positioned strategically to catch the eye, with an emphasis on drama rather than historical accuracy. Anticipating that visitors would pause before continuing to the second floor, Barnard concentrated many compelling objects in tight juxtapositions around the staircase. Works in various media and from different centuries came together at this focal point, inviting close looking and reflection.

Pilaster, late 12th century. Made in Languedoc. French. Stone, 40 3/8 × 13 5/8 × 5 3/4 in. (102.6 × 34.6 × 14.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY. The Cloisters Collection, 1925 (25.120.119)

Decorated with robust scrolls of acanthus leaves, this pilaster of around 1200 is one of many elements in Barnard’s Cloisters from the monastery of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert in southeastern France. While he never seems to have publicly named his favorite works among his collection, Saint-Guilhem clearly held a special appeal for Barnard’s sensibilities as a sculptor. He remarked that its carvings revealed “the power of the chisel,” and as he fretted that American art students lacked awareness of this art form, he advocated for them to examine high-quality medieval sculptures up close. By placing the pilaster near the base of the stairs, flanked by eye-catching wavy columns that also came from Saint-Guilhem (many of which were actually modern reproductions), Barnard ensured that students and casual visitors alike would notice its spectacular surfaces.

Saint Hubert and the Stag, early 16th century. East French. Limestone with paint, Overall: 34 1/2 x 41 1/2 x 12 3/8 in. (87.6 x 105.4 x 31.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, The Cloisters Collection, 1925 (25.120.284)

Directly over the Saint-Guilhem pilaster, Barnard placed a powerful block carved with the story of Saint Hubert. Though three centuries later in date and thus very different in style, this sculpture also features emphatic undercutting and presents three-dimensional foliage in a technical tour-de-force—a formal similarity that perhaps inspired the pairing. Barnard claimed to have found the superb Saint Hubert embedded in a pigsty wall somewhere near Dijon. This fanciful-sounding provenance may have been invented as a rationale for the artwork’s removal to America at a time when France was newly restricting export licenses. Whether or not it is true, the tale also underscores Barnard’s own sense of showmanship in promoting not only the collection itself, but also his own credentials as an adventurer and a connoisseur.

Domingo Ram (Aragonese, active 1464–1507). Panel with Saint John the Baptist Enthroned from Retable, 15th century. Tempera on wood, gold ground, 53 3/4 x 36 1/4 in. (136.5 x 92.1 cm ). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, The Cloisters Collection, 1925 (25.120.670)

While Barnard regaled visitors with tales of finding forgotten treasures in the French countryside, he also acquired artworks through conventional purchases from art dealers. Most of his Spanish works were likely acquired in this manner, as there is no record that Barnard ever traveled to Spain. Regardless, the Spanish panel paintings were clearly also considered among his highlights. This included a powerful image of John the Baptist, attributed to the Aragonese master Domingo Ram (active 1464–1507), which occupied the landing and brought visitors face-to-face with the saint as they ascended to the second floor.

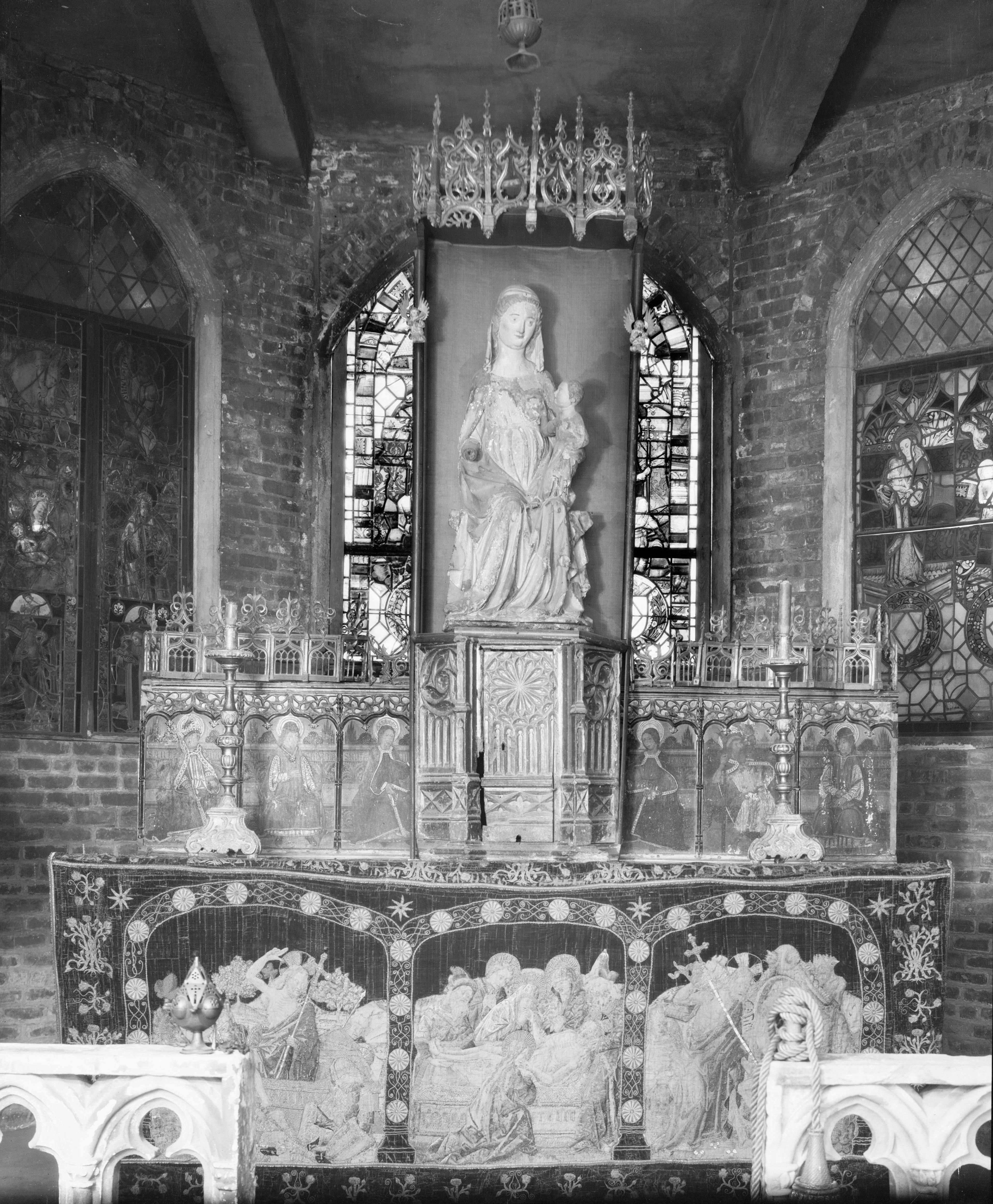

Interior of Barnard’s Cloisters Chapel.

Another evocative reflection of Barnard’s creativity was the chapel he fashioned on the building’s east end. Polygonal in shape, the room featured an elaborately confected altar framed by a motley assemblage of stained-glass panels. While modern museums typically are more restrained in evoking religious spaces, Barnard embraced the dramatic potential of Christian ritual. Though the underlying structure of the altar was likely modern, and its arrangement reflected Barnard’s own taste rather than any specific medieval models, it was adorned with several significant works.

Clockwise from top left: Domingo Ram (Spanish, active 1464–1507). Predella panel with Saint Martial, Saint Sebastian, and Saint Mary Magdalen from Retable and Predella pane with Saint Bridget, Saint Christopher, and Saint Kilian from Retable, 15th century. Tempera on wood, gold ground, 24 1/2 x 41 1/2 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1925 (25.120.674 and 25.120.673); Angel Playing Instrument, 15th century. French. Wood, paint. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1925 (25.120.1055 and 25.120.1056); Textile, Altar Frontal, ca. 1500. French or Italian. Silk, metal thread, 48 1/2 x 108 in. (123.2 x 274.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1925 (25.120.422)

These include two panel paintings, also by Domingo Ram, featuring portrayals of six saints, two tiny sculptures of angelic musicians, and a richly embroidered velvet hanging. Candlesticks and incense burners completed the impression that a church service had just ended, activating a dynamic and suggestive display.

Seated Virgin and Child, ca. 1300–1350. Made in Ile-de-France, France. Walnut with paint and gilding, 48 × 20 1/2 × 14 1/4 in. (121.9 × 52.1 × 36.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, The Cloisters Collection, 1925 (25.120.290)

The place of honor, however, was given to an elegant French Virgin and Child. Barnard promoted an unproven claim that it had been in the abbey church of Saint-Denis (near Paris) until 1848. Given the prestige of Saint-Denis, which had close ties to the French monarchy from the early Middle Ages until the French Revolution, this was almost certainly another imaginative invention designed to increase the sculpture’s mystique. After Barnard’s time, however, many layers of postmedieval overpaint that obscured the original surfaces were removed, revealing a sculpture of uncommonly high quality. Though it is doubtful that the connection to Saint-Denis can ever be verified, Barnard was not wrong to associate the sculpture with the most elite artists and patrons of Gothic France.

Left: An image from Barnard’s Cloisters of the Knight of the d'Aluye family, a coat of arms bearing a cross, and a coat of arms bearing a pig. Right: Contemporary view of Knight of the d'Aluye family, after 1248–by 1267. Limestone, 13 x 33 1/2 x 83 1/2 in. (33 x 85.1 x 212.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1925 (25.120.201)

An effigy from the Loire Valley, made to commemorate a knight of the d’Aluye family, reveals Barnard’s tendency to privilege compelling storytelling over historical accuracy. Photographs show the effigy resting on a modern brick base, to which Barnard affixed several stone coats of arms. These shields have no relationship to the effigy: they belonged instead to the fourteenth-century abbots of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert. (Incidentally, this was the same monastery that was the source of the deeply carved pilaster set before the stairwell.) Barnard, always seeking to capture the imagination of the public, likely felt the shields would have a greater impact if linked to the swashbuckling image of a knight, instead of the comparatively dull identities of faceless monks.

Although Barnard was clearly willing to embellish and even invent the tales behind the artworks, he still sought to evoke medieval settings, and his installations reflected a remarkable understanding of space. Nowhere is his desire to draw upon the historical imagination clearer than in his coining of the term Cloisters as a name for his museum—a moniker that proved so compelling that The Met retained it after the 1925 purchase and the 1938 reopening. But what, exactly, is a cloister?

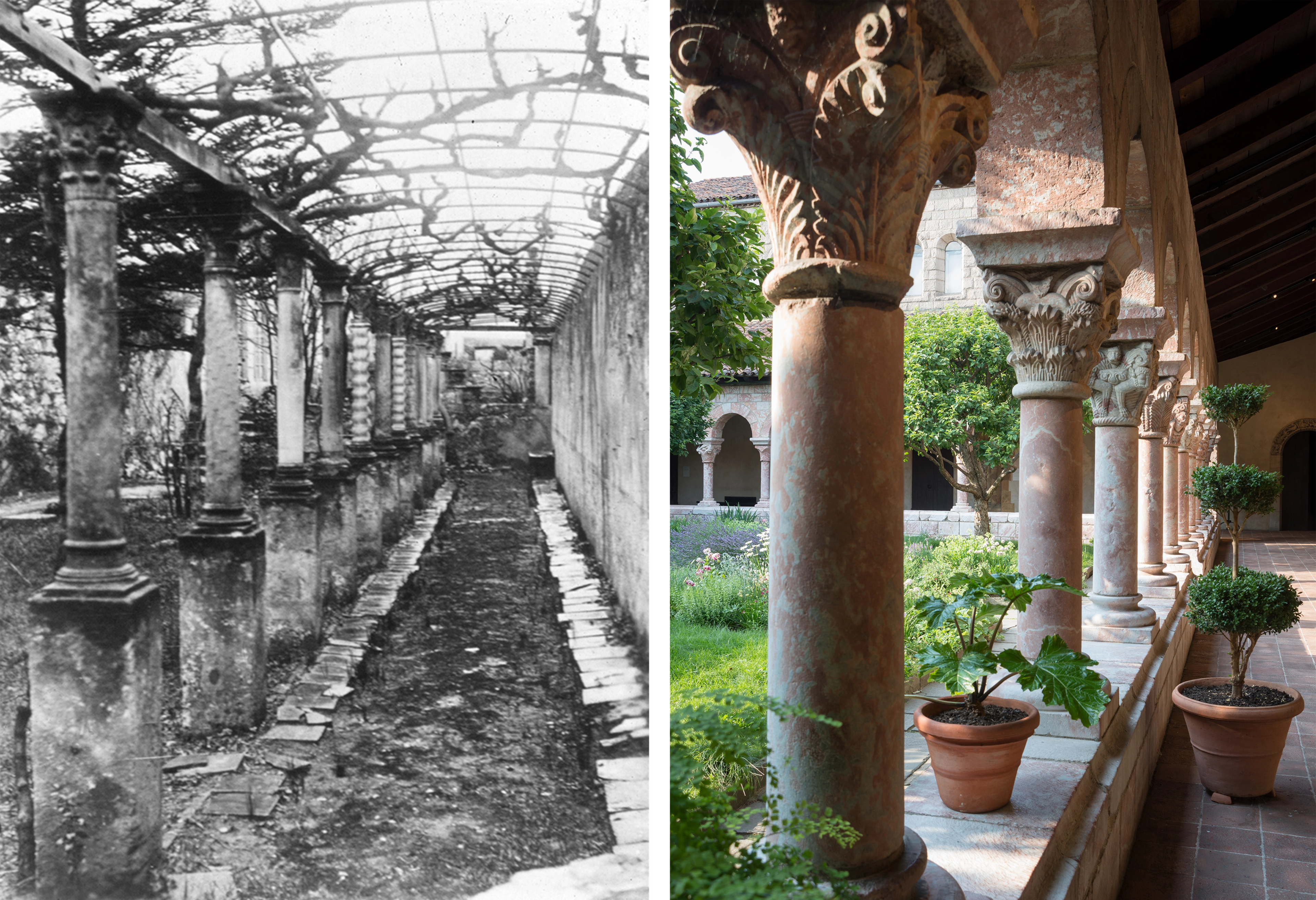

Left: Cuxa Cloister installed in Barnard’s original Cloisters. Right: Cuxa Cloister today, at The Met Cloisters.

An important physical and metaphorical space in a medieval monastery, a cloister is a courtyard typically surrounded by covered walkways and adorned with decorative arcades. Barnard collected elements of several French cloisters during his travels and attempted to suggest their original appearances in his displays both inside and outside of his museum.

Some of the best known of these cloister fragments come from the monastery of Saint-Michel de Cuxa in the French Pyrenees. Many of the distinctive pink marble sculptures, carved in the 1130s, had been removed from the site following the French Revolutionary government’s confiscation and privatization of the monastic property in 1791. By the nineteenth century, much of the Cuxa Cloister had been dismantled and dispersed, its components decorating private homes and businesses.

Left: Elements from the Saint-Guilhem Cloister, before they were purchased by Barnard, in Pierre-Yon Vernière’s Garden. Right: Contemporary view of the Cuxa Cloister.

A magistrate from Aniane, near Saint-Guilhem, named Pierre-Yon Vernière, for example, had many sculptures from both the Saint-Guilhem and Cuxa Cloisters decorating his gardens. In 1906, Barnard purchased these and other elements through art dealers in Paris and Carcassonne. Inspired by the dramatic forms and unusually colored stone of the Cuxa capitals, he traveled to Prades, a town near the monastery, in the following year and started buying additional carvings from the local people. By 1913, mounting tensions with local authorities prompted him to gift several of his acquisitions to the French nation before hastily shipping the rest to New York.

Views of Saint-Guilhem (left) and Cuxa (right) as they exist in France today.

Today, Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert and Saint-Michel de Cuxa remain vibrant and vital sites of cultural heritage, welcoming visitors from around the world. The monuments themselves remain standing, with many portions of their cloisters still extant. Barnard’s role in acquiring and displaying elements from these special places remains a significant subject of scholarship on both sides of the Atlantic, prompting French and American scholars to engage in active dialogue with one another.

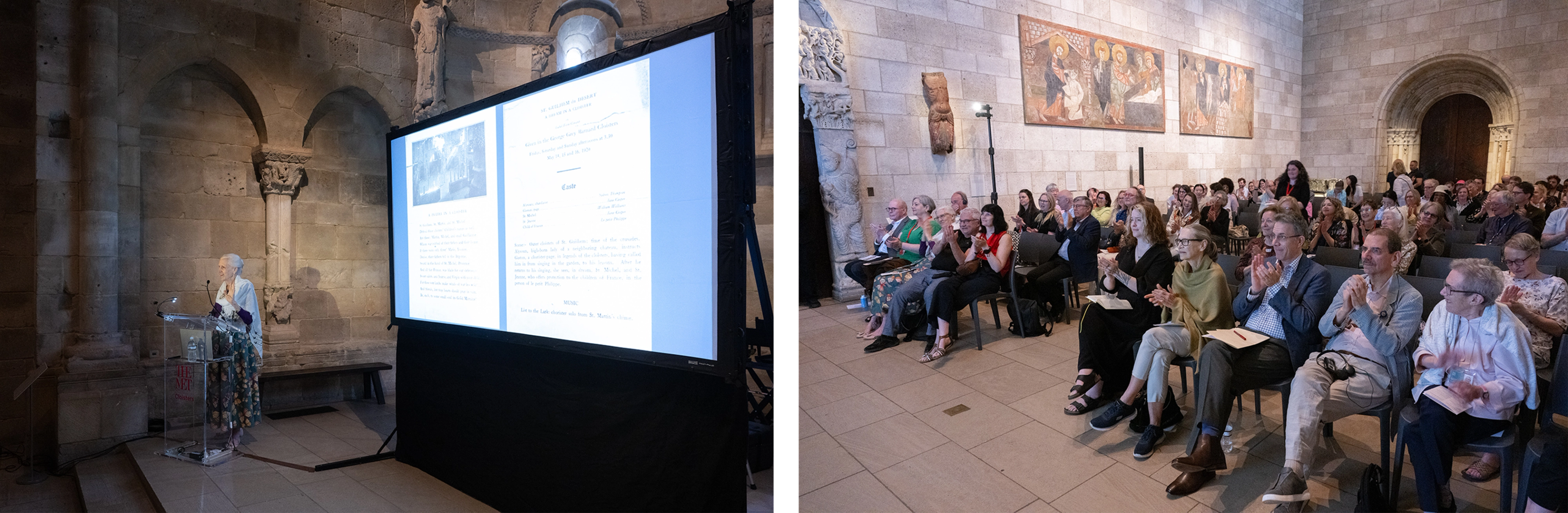

Scenes from The Met Cloisters 1925/2025 Symposium. Courtesy of Filip Wolak Photography

The centennial of The Met’s acquisition of Barnard’s collection presented an opportunity to renew these conversations under the aegis of The Met Cloisters 1925/2025, the title given to both a series of special events (PDF) and a gallery installation. In June, a three-day gathering brought together curators, educators, writers, students, and interested members of the public at The Met Cloisters. The main event, a scholarly symposium open to all, took place on June 12, one hundred years to the day since the official press release announcing the purchase of Barnard’s Cloisters. Invited speakers included representatives from Saint-Michel de Cuxa and Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, as well as the creators of a digital reconstruction and virtual reality tour of Barnard’s Cloisters. One day before the symposium, a small group of specialized scholars assembled to study materials from Barnard’s Cloisters in detail; on the day after, graduate students participated in a workshop sponsored by the Newberry Library to continue the conversation.

The Met Cloisters 1925/2025 installation in the Saint-Guilhem Cloister. Photo by Julia Perratore

Barnard’s legacy is complicated. Many of the decisions he made would not be replicated today, and yet the impact of his collection on the study and appreciation of medieval art is undeniable. On view through December 2025, The Met Cloisters 1925/2025 explores the history of its legendary precursor by adding a few gems from Barnard’s collection that had previously been in storage to the Saint-Guilhem and Early Gothic galleries (Galleries 3 and 8). Special labels have also been added throughout the galleries to draw attention to other works from Barnard’s Cloisters that were already on view. Printed on brick-red backgrounds that recall Barnard’s walls, these labels feature photographs of the earlier museum’s evocative displays. The goal is to encourage visitors to see the layered history behind the building, and to introduce George Grey Barnard to a broader public as a fellow fan of the Middle Ages, whose efforts culminated in a collection that remains unparalleled among American museums of medieval art.