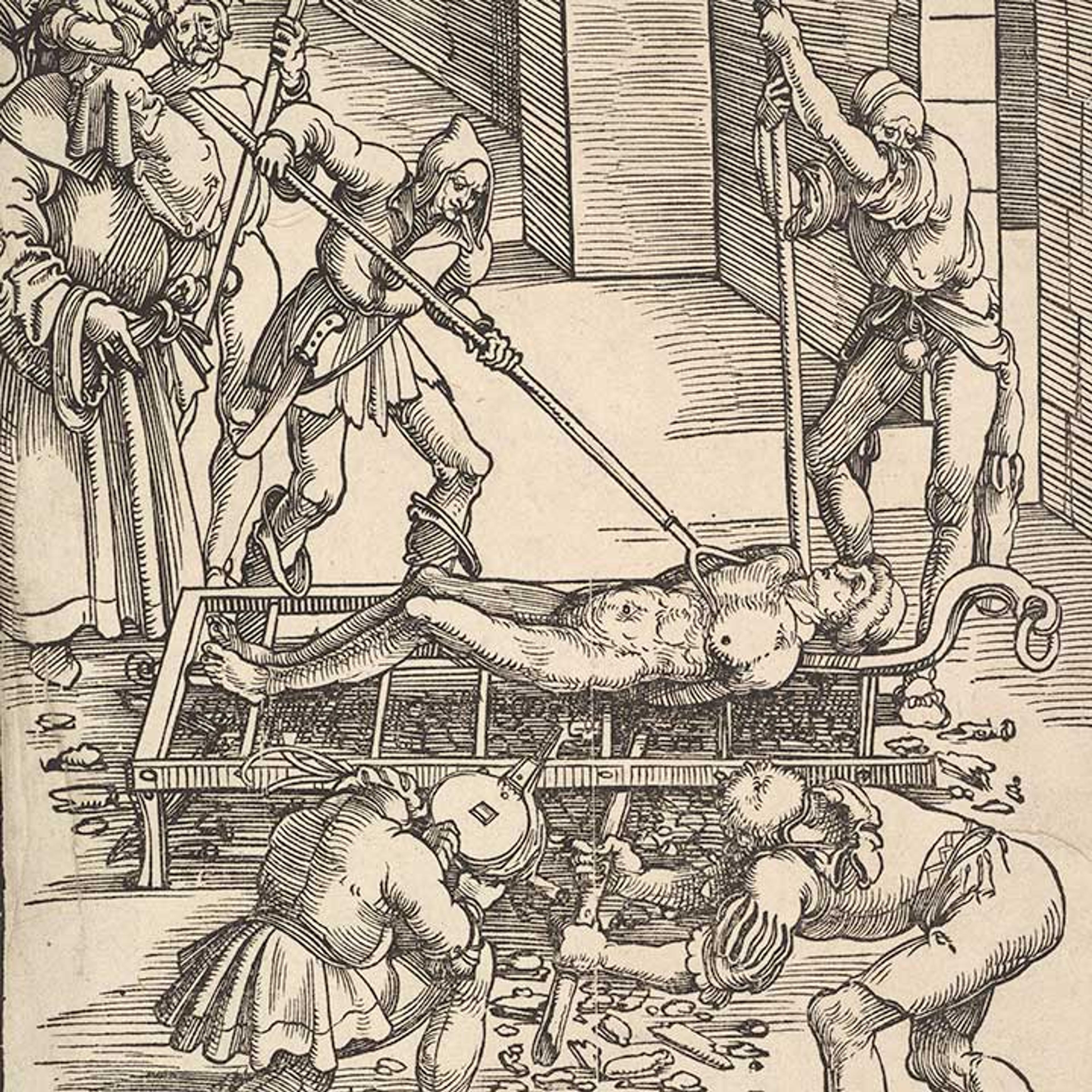

Hans Baldung Grien (German, 1484/85–1545). Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence (detail), ca. 1505. Woodcut, 8 15/16 x 13 3/16 in. (22.7 x 33.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Rogers Fund, 1922 (22.67.55)

«My family is deeply engrossed in Game of Thrones, whereas I—despite the show's quasi-medieval setting, complete with dragons and castles—simply can't abide the persistent violence. Personally, I'm more entranced by the confectionery kingdom of Disney's Sleeping Beauty: what's not to love about fairy godmothers flying about an enameled tabernacle in the early palace scenes? However, George R. R. Martin, author of the novels on which the TV series is based, states that he is not interested in "the Disneyland Middle Ages." In defense of Game of Thrones' brutal, raw imagery, Martin asserts that "the atrocities [in Game of Thrones]. . . pale in comparison to what can be found in any good history book." Disney aside, there can be little doubt that Martin is right about the violent reality of any age—whether medieval or modern.»

In life, on screen, and in art, grisly violence pervades both secular and sacred realms, flowing seamlessly from castle to cathedral. Again and again, medieval artists conjure up the excruciating torments of saints. Beheadings, flayings, stonings, people roasting on a grill: all provide fodder for the artistic imagination. If we consider images in The Met collection of two saints whose feasts are celebrated in the steamy month of August—Saint Bartholomew and Saint Lawrence—we find a medieval corollary of what I abhor on television. Curiously, while I shrink away from the TV screen, I find that when violence is placed in the hands of the best medieval artists, the result is often deeply resonant, simultaneously attractive and repulsive, hitting that critical cerebral spot where pleasure and pain meet.

The Limbourg Brothers (Franco-Netherlandish, active France, by 1399–1416). The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, from The Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry (detail, folio 161), 1405–1408/09. Tempera, gold, and ink on vellum, 9 3/8 x 6 x 11/16 in. (23.8 x 17 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1)

Patently erotic violence infuses the Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew in The Belles Heures at The Met Cloisters. Taut ropes bind the saint's perfect, naked body, and a cluster of officials hover all too close and stare unabashedly as sharp steel meets tender flesh.

Pacino di Bonaguida (Italian, active Florence, 1302–ca. 1340). Manuscript leaf with the Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, from a laudario, ca. 1340. Tempera, gold, and ink on parchment, 18 1/2 x 13 3/4 in. (47 x 35 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 2006 (2006.250)

In Pacino di Bonaguida's (1280–ca. 1340) Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew, the flaying and beheading of the saint are staged as a kind of bloody ballet. Cue the music, for in its day, this torture was something to sing about! The artist painted these side-by-side images of Saint Bartholomew as a kind of title page for a hymn that Florence's finest choir sang on the martyr's feast day, August 24.

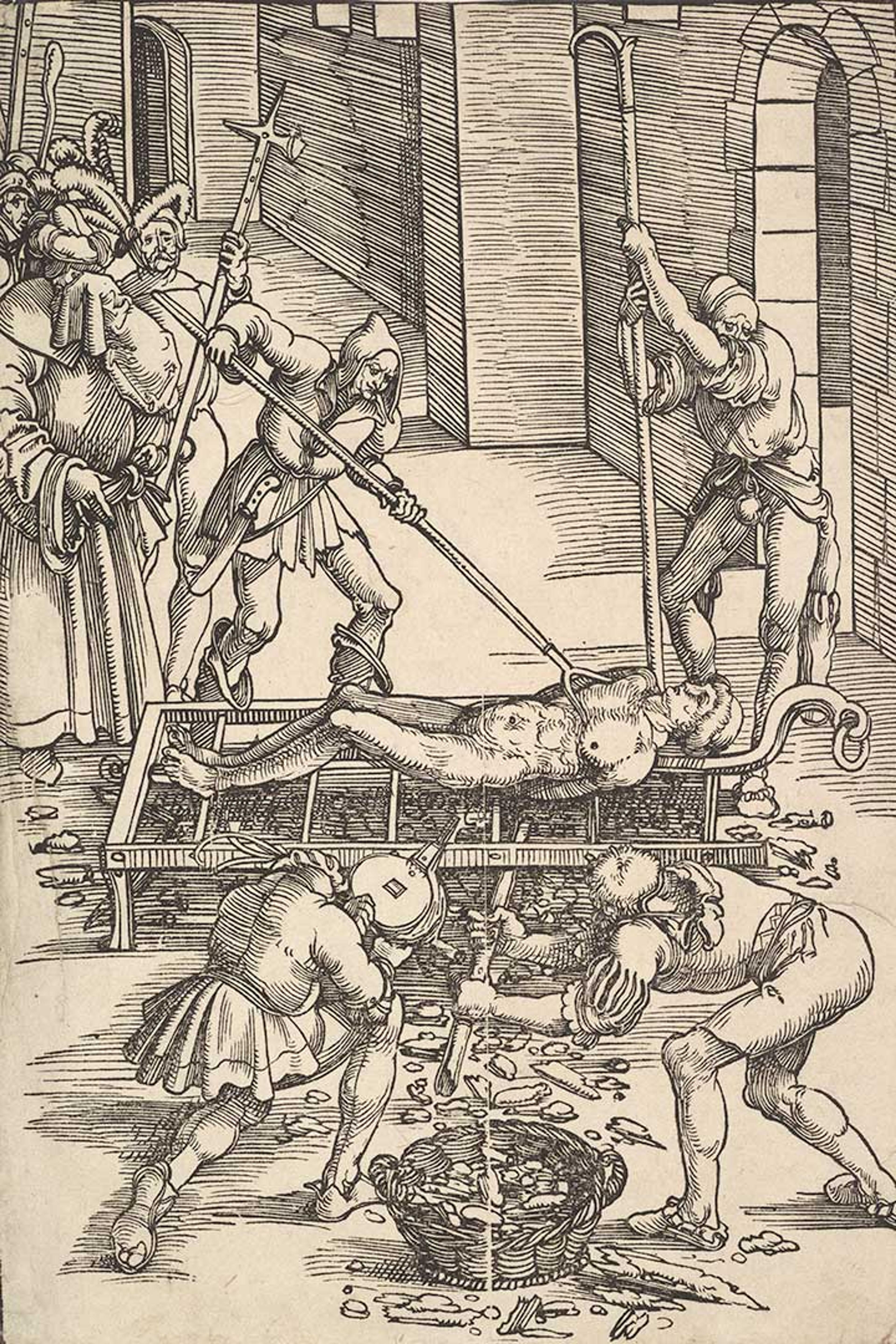

Hans Baldung Grien (German, 1484/85–1545). Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence, ca. 1505. Woodcut, 8 15/16 x 13 3/16 in. (22.7 x 33.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Rogers Fund, 1922 (22.67.55)

For the dramatic Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence, Hans Baldung Grien (ca. 1484–1545) chose the stark black-and-white print medium to suggest the cold, heartless violence of the saint's execution. Even in their absence of color, figural poses convey the intensity of fire. The saint's body curls up, like frying bacon, down to his toes. The smell is clearly horrendous, and men cover their noses. The executioner forcibly holds Lawrence down with a huge, forked implement as faceless men fan and fuel the flames. The saint's particular torment has, rather comically, earned him a place as patron of barbecues, a seasonally appropriate designation for his feast day on August 10.

Don Simone Camaldolese (Italian, active Florence, 1375–1398). Manuscript illumination with Saint Lawrence in an initial C, from a gradual, ca. 1380–90. Tempera, ink, and gold on parchment, 5 7/8 x 7 9/16 in. (15 x 19.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Mrs. A. M. Minturn, 1890 (90.61.2)

Sometimes artists spare us the gory details, and the curtain closes on the theater. For his illustration of the feast of Saint Lawrence, the Florentine illuminator Don Simone (active 1375–1398) has created an exquisitely painted but, to the uninitiated, perhaps confusing image. At first glance, the saint appears to hold a tall window in one hand. In fact, this is the grill of his martyrdom, here a singularly non-threatening object. Faced with this image, we need not avert our eyes, but are we as powerfully affected in the absence of broken bodies?