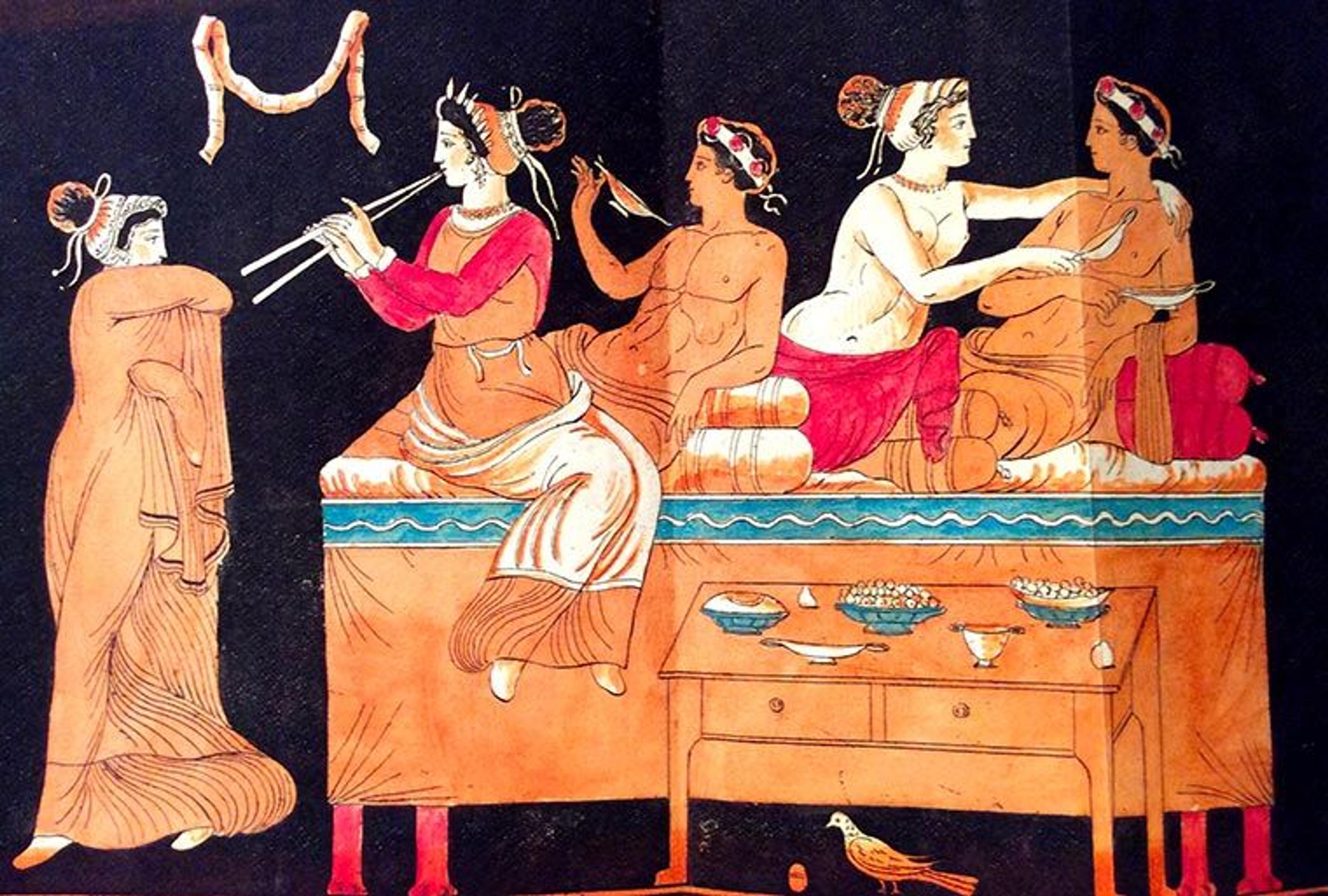

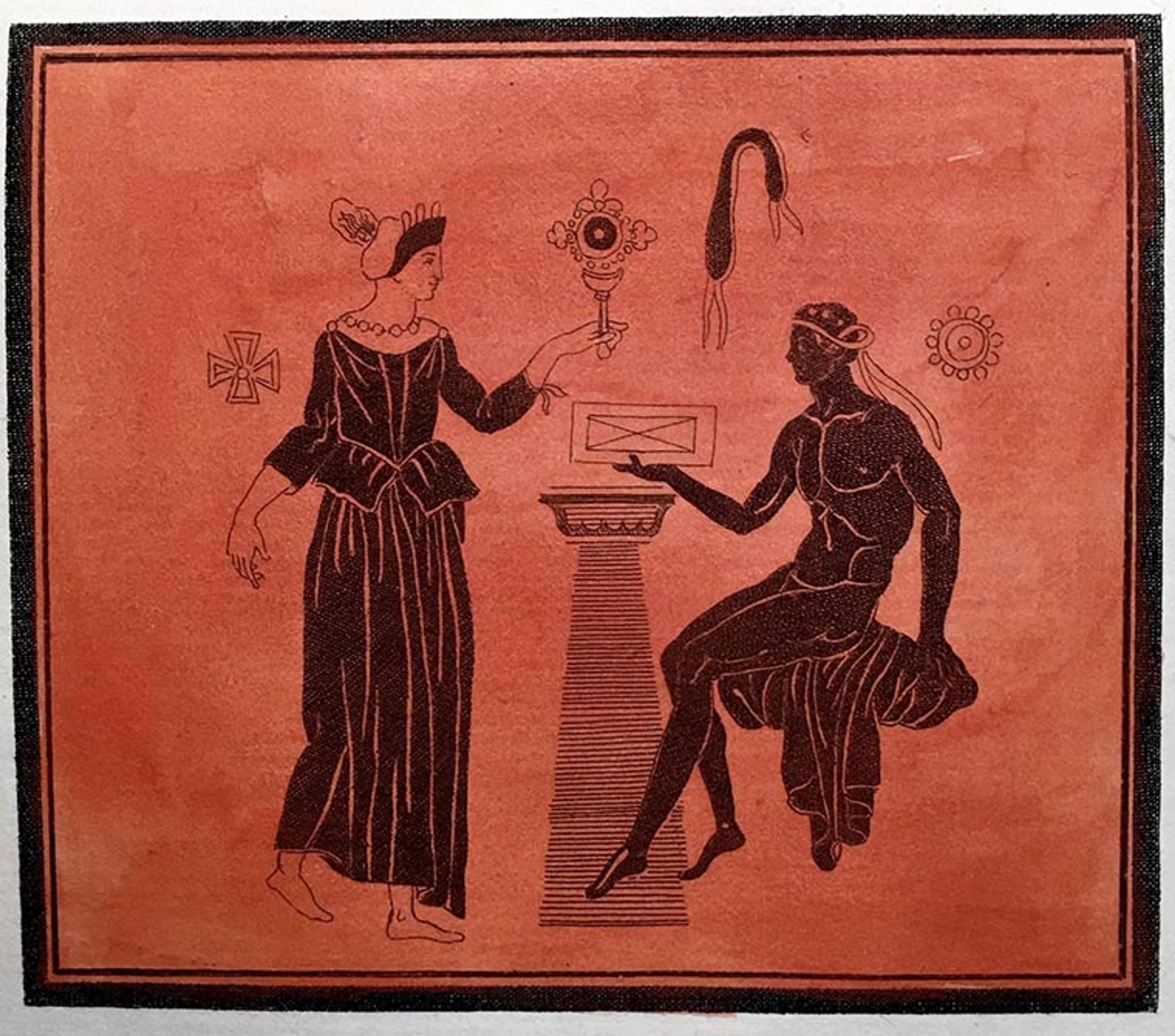

Sir William Hamilton, Collection of Etruscan, Greek, and Roman Antiquities from the Cabinet of the Honble. Wm. Hamilton (Naples: Imprimé par F. Morelli, 1767).

As a librarian with a background in the classics, I am always thrilled when I come across books on antiquities in the Thomas J. Watson Library collection. Recently, I came across a reference to Sir William Hamilton (1730–1803) and, to my delight, a quick search on Watsonline revealed several of his publications.

Hamilton is a fascinating character. As Envoy Extraordinary to Naples, he served as a British diplomat to Ferdinand I (1751–1825), King of the Two Sicilies. He was also a collector and a polymath, with an enormous sense of curiosity. His presence in the court of King Ferdinand allowed him free range to indulge in his intellectual passions, whether it was researching the eruptions of nearby Vesuvius, playing his violin with a very young Mozart, or collecting antiquities, his favorite pastime. Readers of modern fiction may be familiar with him as the protagonist in Susan Sontag's 1992 novel The Volcano Lover, while fans of British history are aware of the scandalous love affair between Hamilton's second wife, Emma (1765–1815), and Lord Horatio Nelson (1758–1805).

Adam Buck (Irish, 1759–1833). Portrait of a Woman, Said to Be Emma (1765–1815), Lady Hamilton, 1804. Ivory, diam. 1 1/4 in. (32 mm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Moses Lazarus Collection, Gift of Josephine and Sarah Lazarus, in memory of their father, 1888–95 (95.14.81)

Son of Lord Archibald and Lady Jane Hamilton and the youngest of four brothers, William joined the army at sixteen but left it soon after his marriage to Catherine Barlow. Their marriage was a happy one, based on a mutual love of music. He joined the British Parliament in 1761. Not long after, Catherine became gravely ill and her physician encouraged them to move to a warmer climate. When he heard the ambassadorial position in Naples was soon to be open, he bid on it and was appointed in 1764.

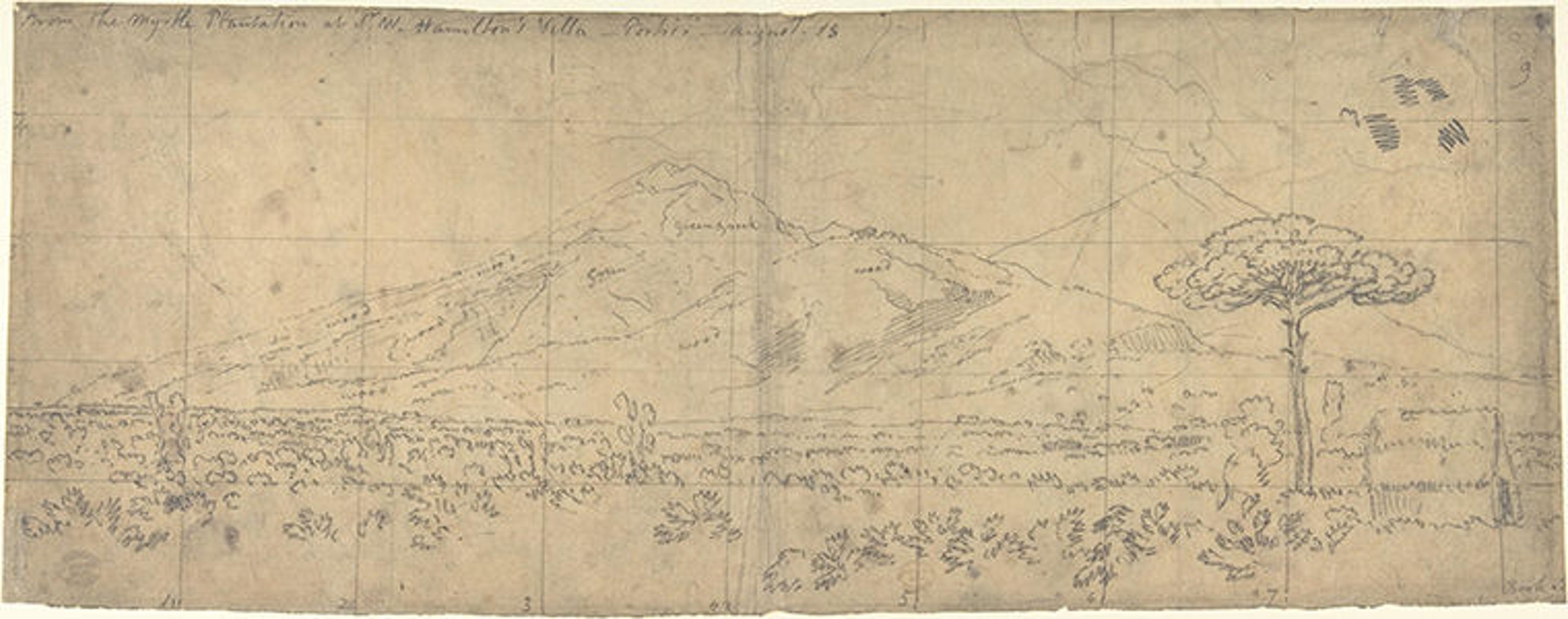

John Robert Cozens (British, 1752–1797). View of Vesuvius, 1782. Graphite on tracing paper, 7 1/2 x 18 7/8 in. (19.1 x 47.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1907 (07.282.4)

Hamilton was a consummate multitasker: in addition to his ambassadorial duties, he researched natural history and collected antiquities. He was obsessed with Vesuvius—so much so that his friends feared he might share the same fate as Pliny the Elder, who supposedly died in an attempt to get closer to an eruption. Hamilton spent hours watching the volcano, taking notes on eruptions, and collecting specimens. He wrote letters about his observations and published them in 1776, accompanied by fifty-four gouache drawings by Pietro Fabris (active 1740–1792). Watson Library has a folio facsimile edition of this work, Campi Phlegræi: Observations on the Volcanoes of the Two Sicilies, as They Have Been Communicated to the Royal Society Of London.

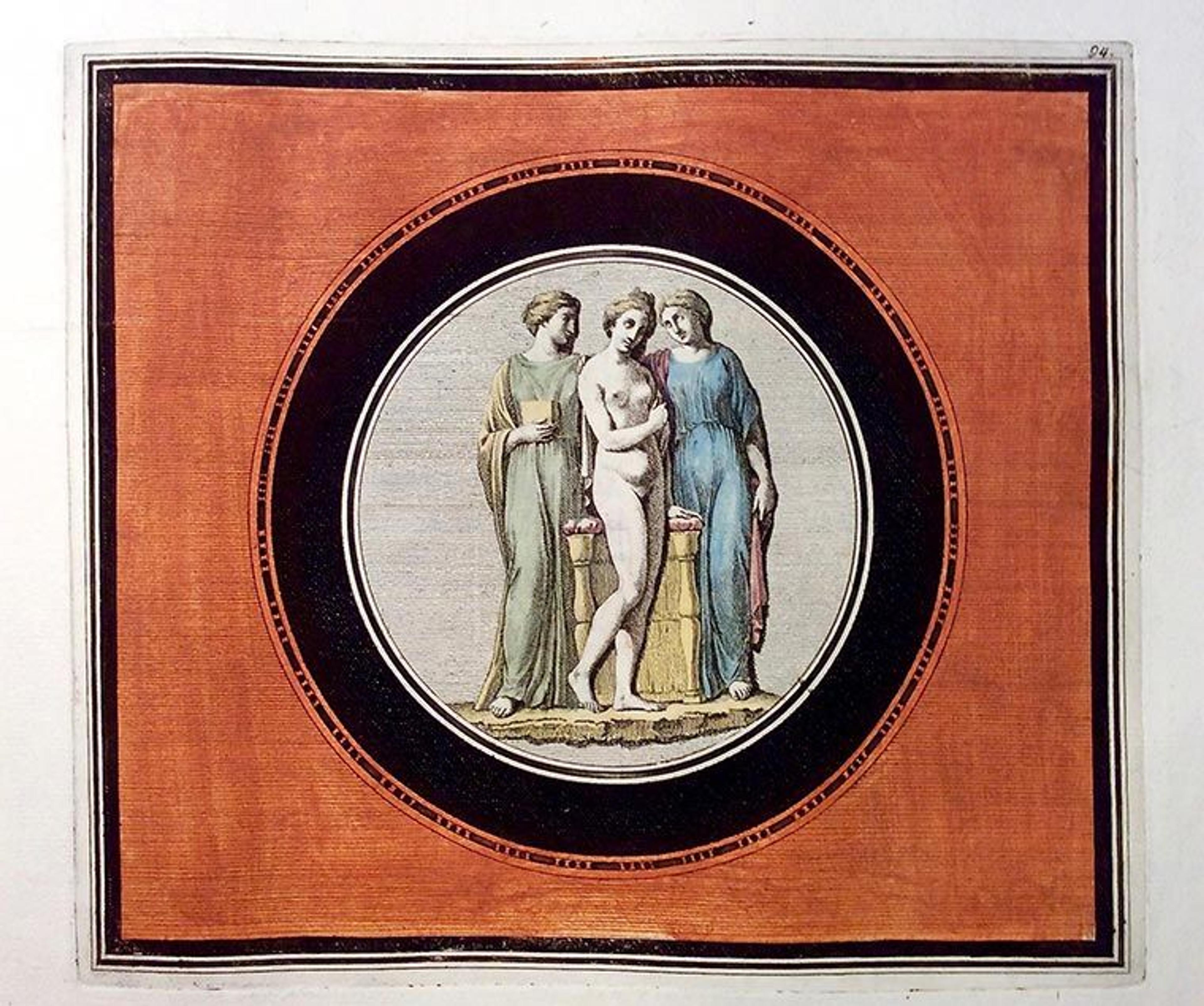

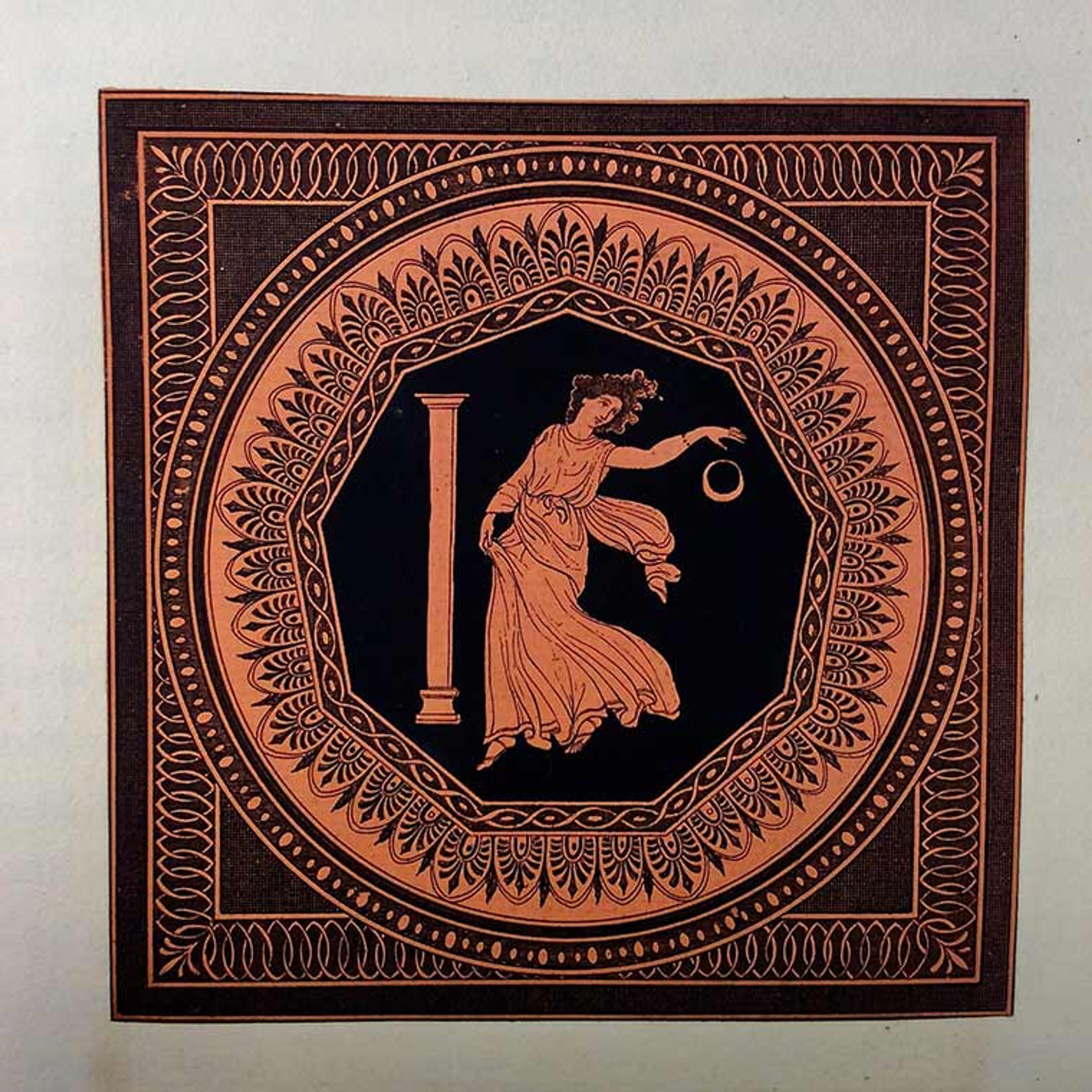

Hamilton is best known for the works he commissioned on his own collections of classical antiquities. The first catalogue, Antiquités Etrusques, Grecques, et Romaines Tirées du Cabinet de M. Hamilton (often abbreviated AEGR), a four-volume folio set published in Naples in 1766–67, is lushly illustrated with hand-colored engraved plates. Baron d'Hancarville (Pierre-François Hugues), a sort-of rogue scholar of antiquities, wrote the catalogue's text. D'Hancarville attempted to formulate a stylistic chronology of ancient vase painting, which was both influenced by and in contradiction to similar theories of the famous German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768). The English language version of AEGR is entitled Collection of Etruscan, Greek, and Roman Antiquities from the Cabinet of the Honble. Wm. Hamilton.

Sir William Hamilton, Collection Of Etruscan, Greek, And Roman Antiquities from the Cabinet of the Honble. Wm. Hamilton(Naples: Imprimé par F. Morelli, 1767).

Sir William Hamilton, Collection Of Etruscan, Greek, And Roman Antiquities from the Cabinet of the Honble. Wm. Hamilton (Naples: Imprimé par F. Morelli, 1767).

Sir William Hamilton, Collection Of Etruscan, Greek, And Roman Antiquities from the Cabinet of the Honble. Wm. Hamilton (Naples: Imprimé par F. Morelli, 1767).

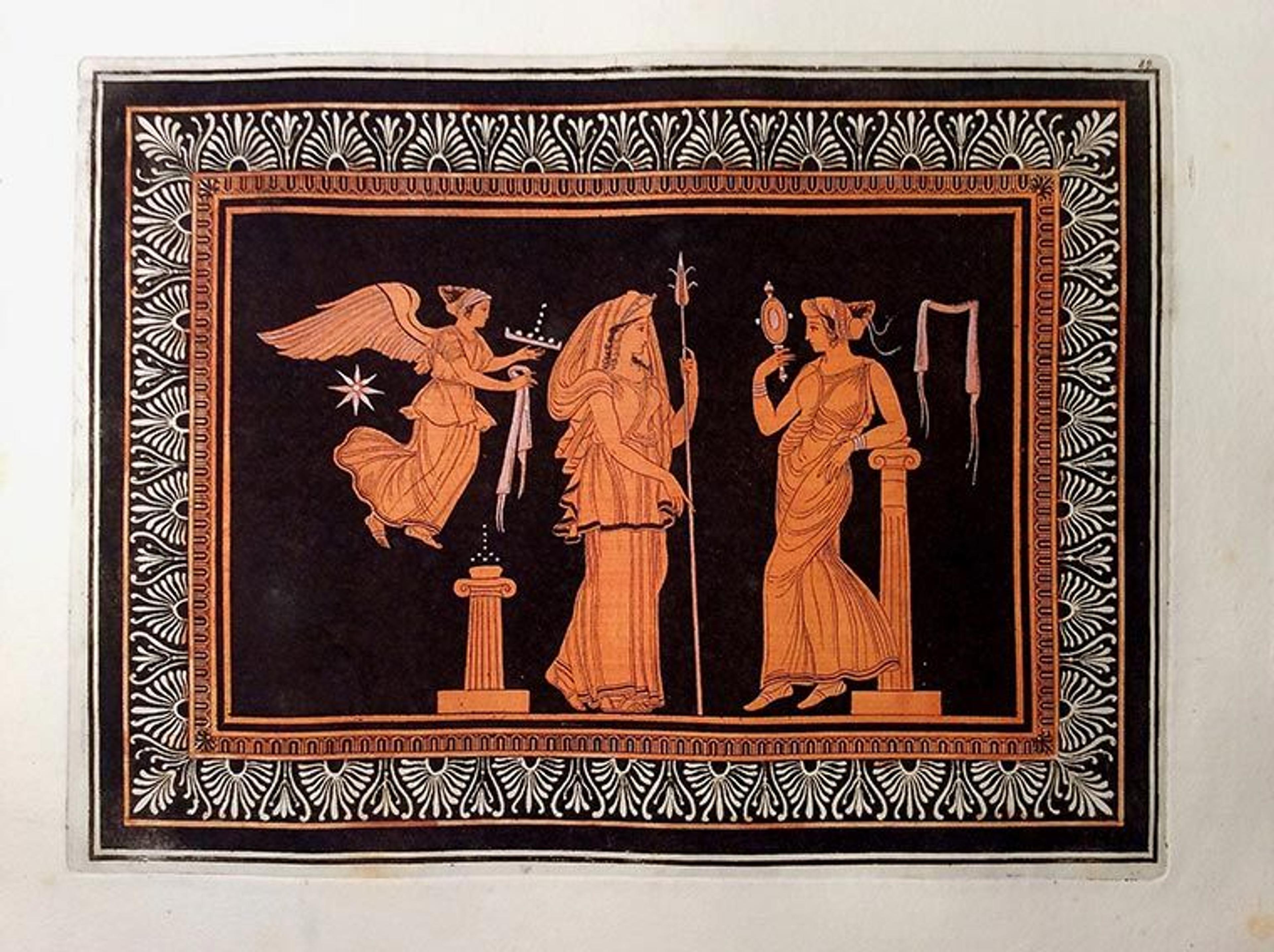

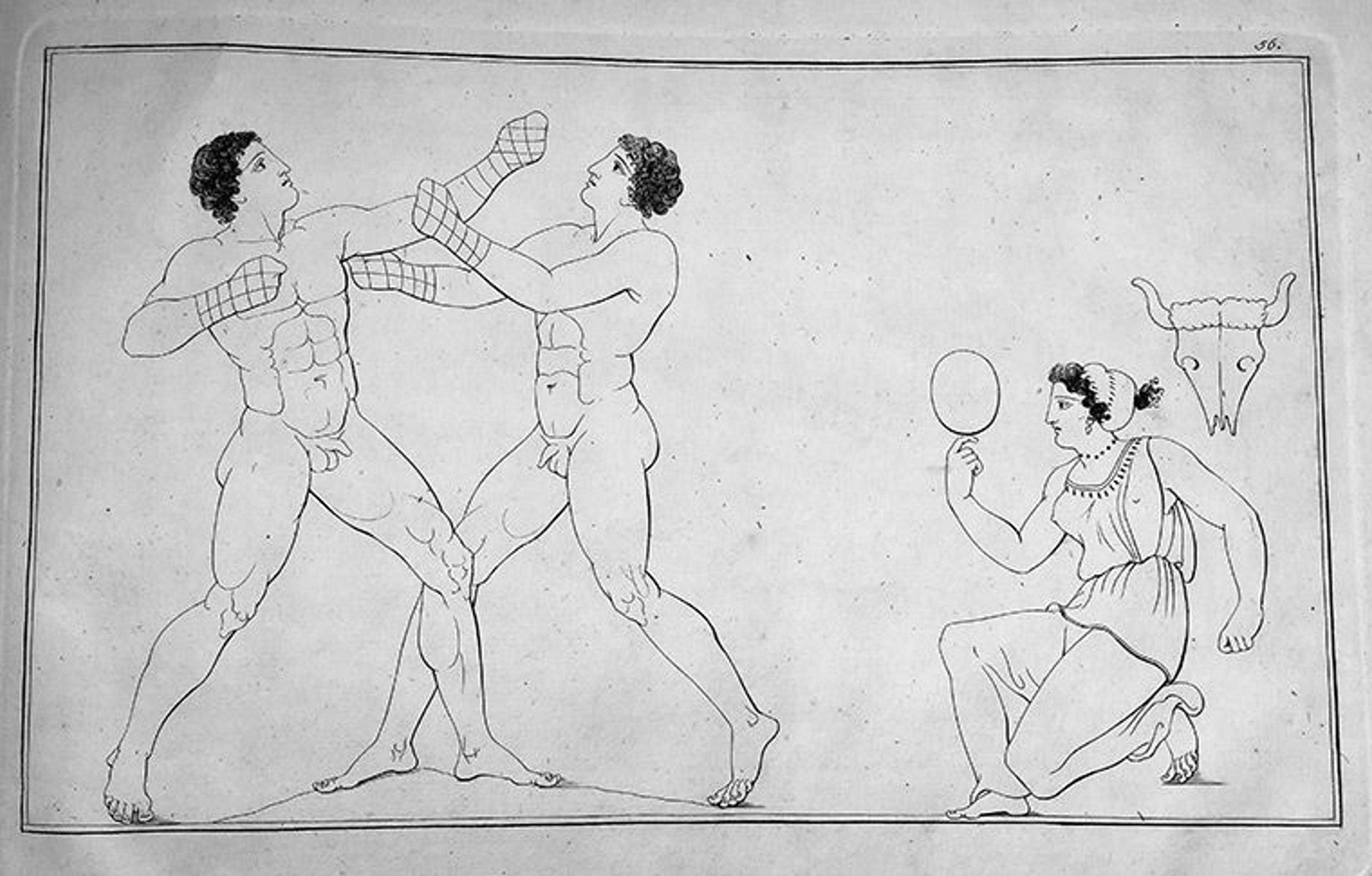

Hamilton's first collection of antiquities was sold to the British Museum in 1772. No sooner had he sold this collection than he began to collect again. The catalogue for his second vase collection was edited and illustrated by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein (1751–1829) and titled Collection of Engravings from Ancient Vases Mostly of Pure Greek Workmanship Discovered in Sepulchres in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies but Chiefly in the Neighbourhood of Naples During the Course of the Years MDCCLXXXIX and MDCCLXXXX. The outline engravings in this set are valuable not just for their stark beauty, but also because the ship carrying the vases, the HMS Colossus, sunk in 1798 and the cargo was lost; the engravings are the sole remaining record.

Sir William Hamilton, Collection of Engravings from Ancient Vases Mostly of Pure Greek Workmanship Discovered in Sepulchres in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies but Chiefly in the Neighbourhood of Naples During the Course of the Years MDCCLXXXIX and MDCCLXXXX (Naples: Wm. Tischbein, 1791–95).

Sir William Hamilton, Collection of Engravings from Ancient Vases Mostly of Pure Greek Workmanship Discovered in Sepulchres in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies but Chiefly in the Neighbourhood of Naples During the Course of the Years MDCCLXXXIX and MDCCLXXXX (Naples: Wm. Tischbein, 1791–95).

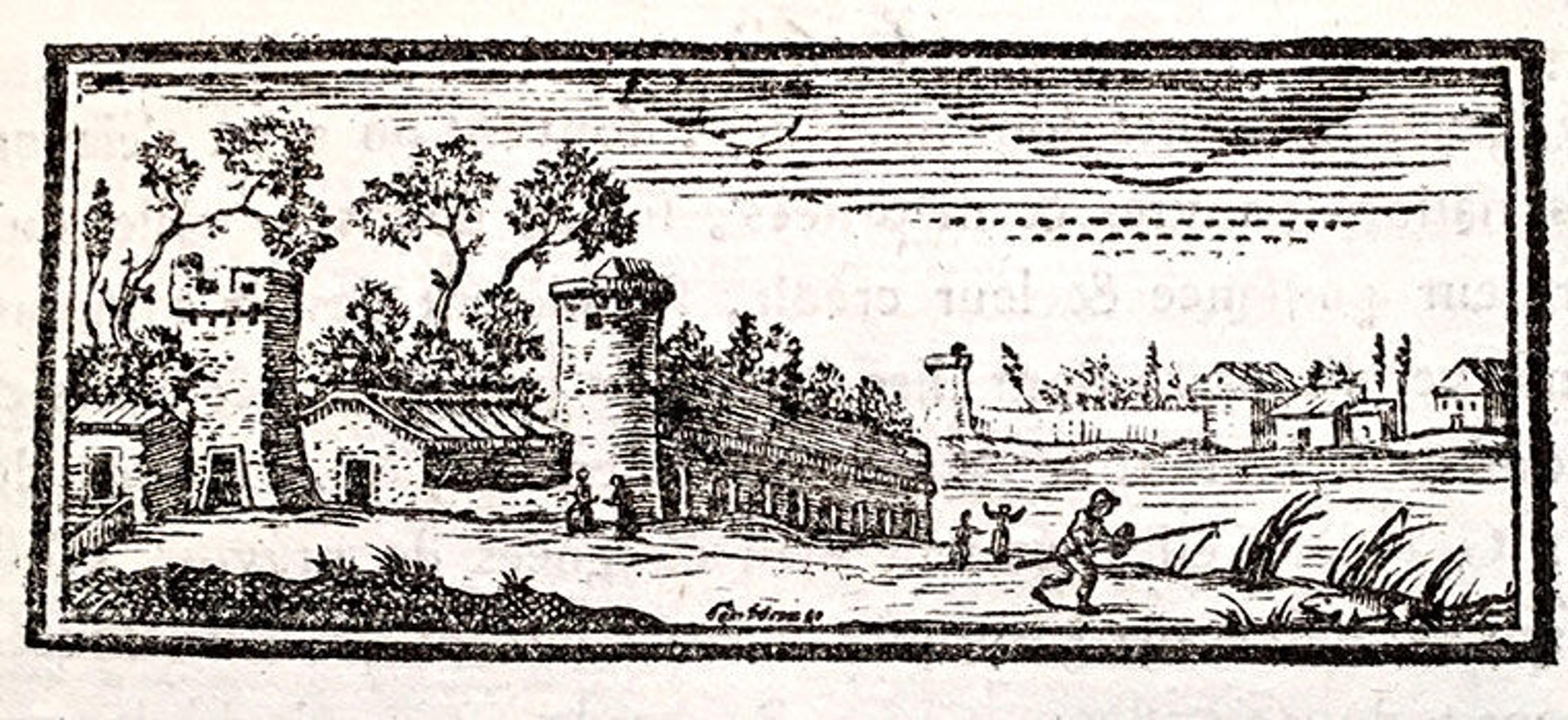

While those catalogues were created as large folio editions meant as luxury items for aristocratic libraries, smaller editions were published for the general public. Hancarville put out a smaller edition of Antiquités Étrusques, Grecques Et Romaines . . . Gravées Par F. A. David. Avec Leurs Explications. This edition had delicate line engravings by François Anne David (1741–1824), a French engraver. I am particularly fond of its woodcut title vignettes, which harken back to classical pastoral poetry.

Woodcut vignette from Antiquités Étrusques, Grecques Et Romaines . . . Gravées Par F. A. David. Avec Leurs Explications (Paris: L'auteur, 1785–87).

Woodcut vignette from Antiquités Étrusques, Grecques Et Romaines . . . Gravées Par F. A. David. Avec Leurs Explications (Paris: L'auteur, 1785–87).

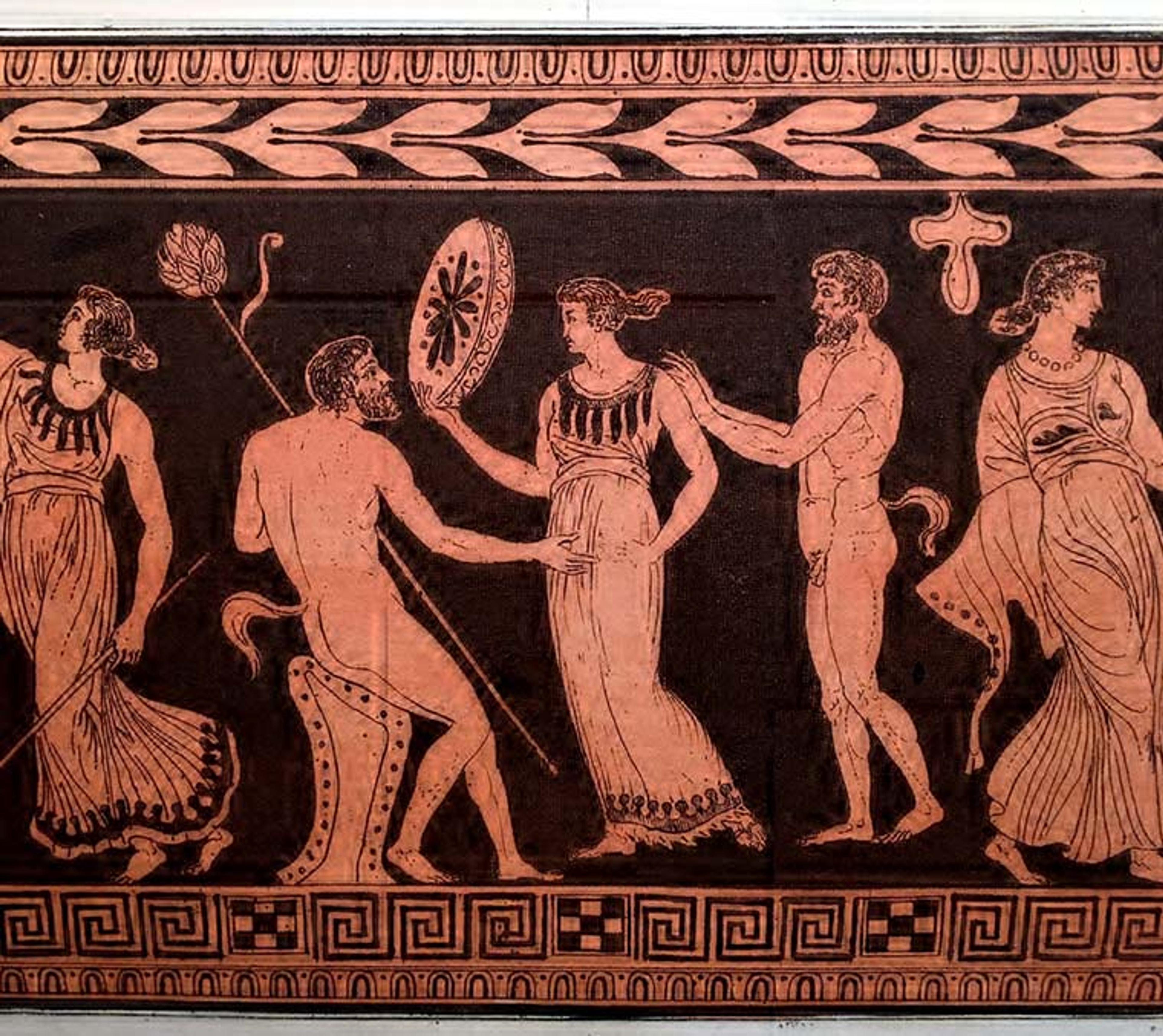

The outline engravings by Thomas Kirk (1765–1797), an English book illustrator, are also delightful viewing in Outlines from the Figures and Compositions upon the Greek, Roman, and Etruscan Vases of the Late Sir William Hamilton: With Engraved Borders Drawn and Engraved by the Late Mr. Kirk.

Outlines from the Figures and Compositions upon the Greek, Roman, and Etruscan Vases of the Late Sir William Hamilton: With Engraved Borders Drawn and Engraved by the Late Mr. Kirk (London: William Miller, 1804).

Outlines from the Figures and Compositions upon the Greek, Roman, and Etruscan Vases of the Late Sir William Hamilton: With Engraved Borders Drawn and Engraved by the Late Mr. Kirk (London: William Miller, 1804).

The publication of Hamilton's collections greatly influenced English decorative artists, artisans, and scholars of the period. It was Hamilton's primary hope to inspire artists with the depictions of his collection. He had even sent some preliminary engravings to Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795), a renowned English potter and industrialist, to serve as source materials for vases made by his workshop. One of the most famous is his copy of the Portland Vase.

Josiah Wedgwood and Sons (1759–present). Portland Vase, ca. 1840–60. Black basalt ware with white relief decoration, height 10 3/8 in. (26.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1894 (94.4.172)

For the contemporary art historian, the books serve as stepping stones for researching connoisseurship of the period, provenance, and cultural appropriation; for the art lover, they open up a world of timeless, classical beauty.