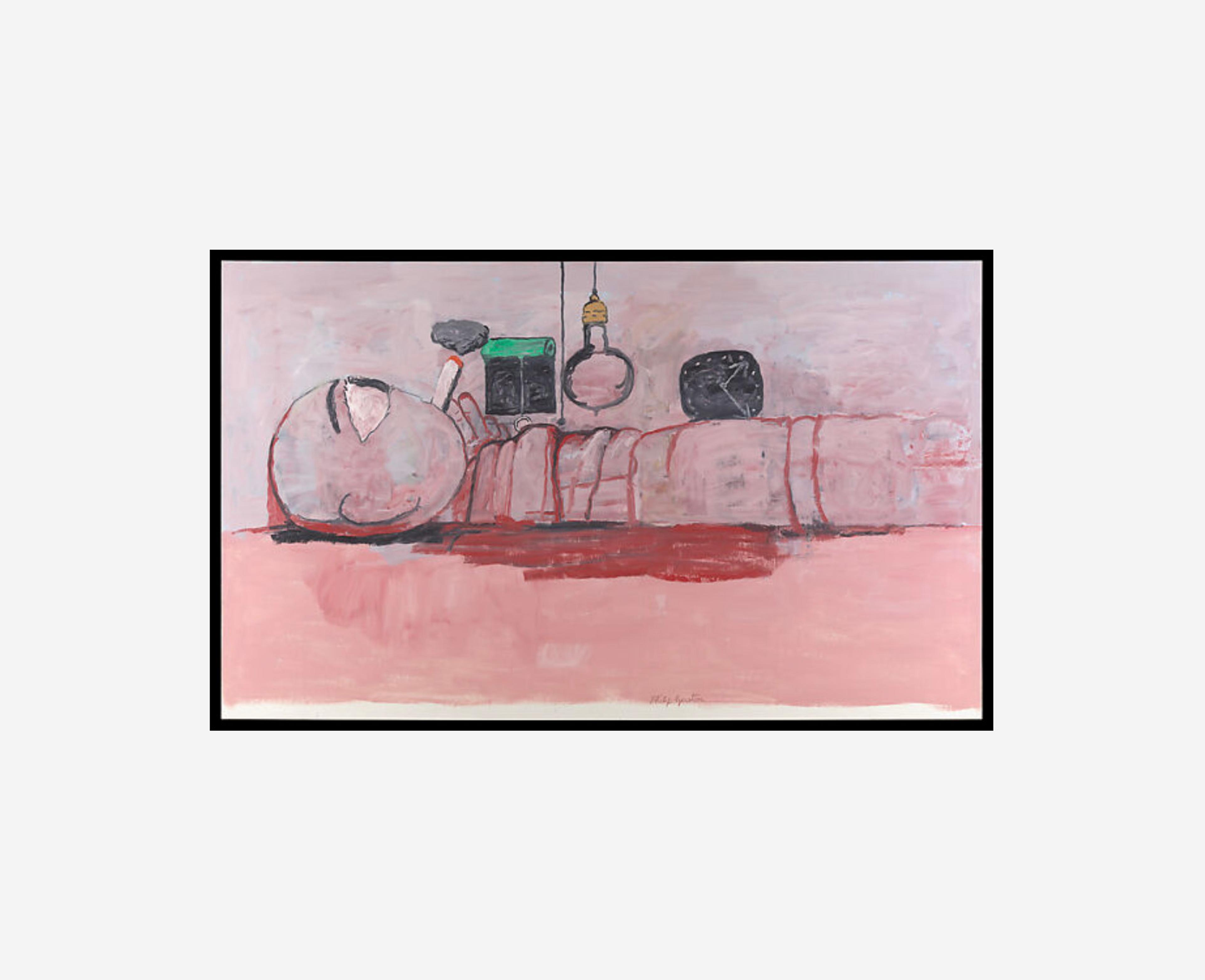

Philip Guston (American, born Canada, 1913–1980). Stationary Figure, 1973. Oil on canvas, 77 1/2 in. × 10 ft. 8 1/2 in. (196.9 × 326.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Musa Guston, 1992 (1992.321.2)

I think it's brilliant: making art look like it's not about skill.

My name is John Baldessari.

I get labeled as a conceptual artist, which I think is a misnomer, but everybody gets a label in life. I get labeled, you know, a California artist, and I think that's a misnomer also, but, then, we get labels. I just would rather be called an artist.

I was interested in Philip Guston when I was in high school and my parents used to subscribe to Life Magazine and his early works were in it. I would tear them out and save them. It was very sophisticated work. And then when he started doing this later work, he got severely criticized: it wasn't art and blah, blah, blah. And I said, well he's on the right track if people are saying that about him.

What I like about him is that he is trying to de-skill himself and take all the sophistication away, you know that he's just like really a dumb artist. And I'm using "dumb" in a good way. So it's this seemingly clumsy but very sophisticated brushwork. They're not slick surfaces, you can see the brushwork.

And then I like his simplicity of choice in subject matter. And I guess it comes out of Van Gogh's painting of a pair of old boots: you know, you don't need to paint a cathedral, you just have to be an interesting painter. It's utter simplicity: those bug eyes, and where's the nose, have we ever seen a mouth? It's almost like the eyebrow and the ear could be interchanged. And his figures are always smoking a cigarette; there's always that dumb cloud of smoke, which if it weren't for the cigarette could be a rock, could be anything! Don't you laugh when you see that?

I think it's macabre humor. It's a laugh that's also shadowed by the thought of the brevity of life. A poetic mind would think that death is absurd and funny. The elements of time: the light and the clock and the short duration of the cigarette. There's more light in the room in which he is than there is outside. It's like a prison cell. He's almost in bondage, you know, with the bedclothes—you might even call that a straightjacket. It's nightmarish, in some way, you know, of being constrained and trapped by time.

I think it's tough to like. I think the average viewer is going to say, "Yeah, my kid can do that." And that would be almost dismissive. But I think it's brilliant: making art look like it's not about skill. He knew that he was going to ruffle feathers and irritate people. I absolutely identify with his courage in doing that. It's one of the things I've always emphasized: you know, don't be a virtuoso and don't be a show off.