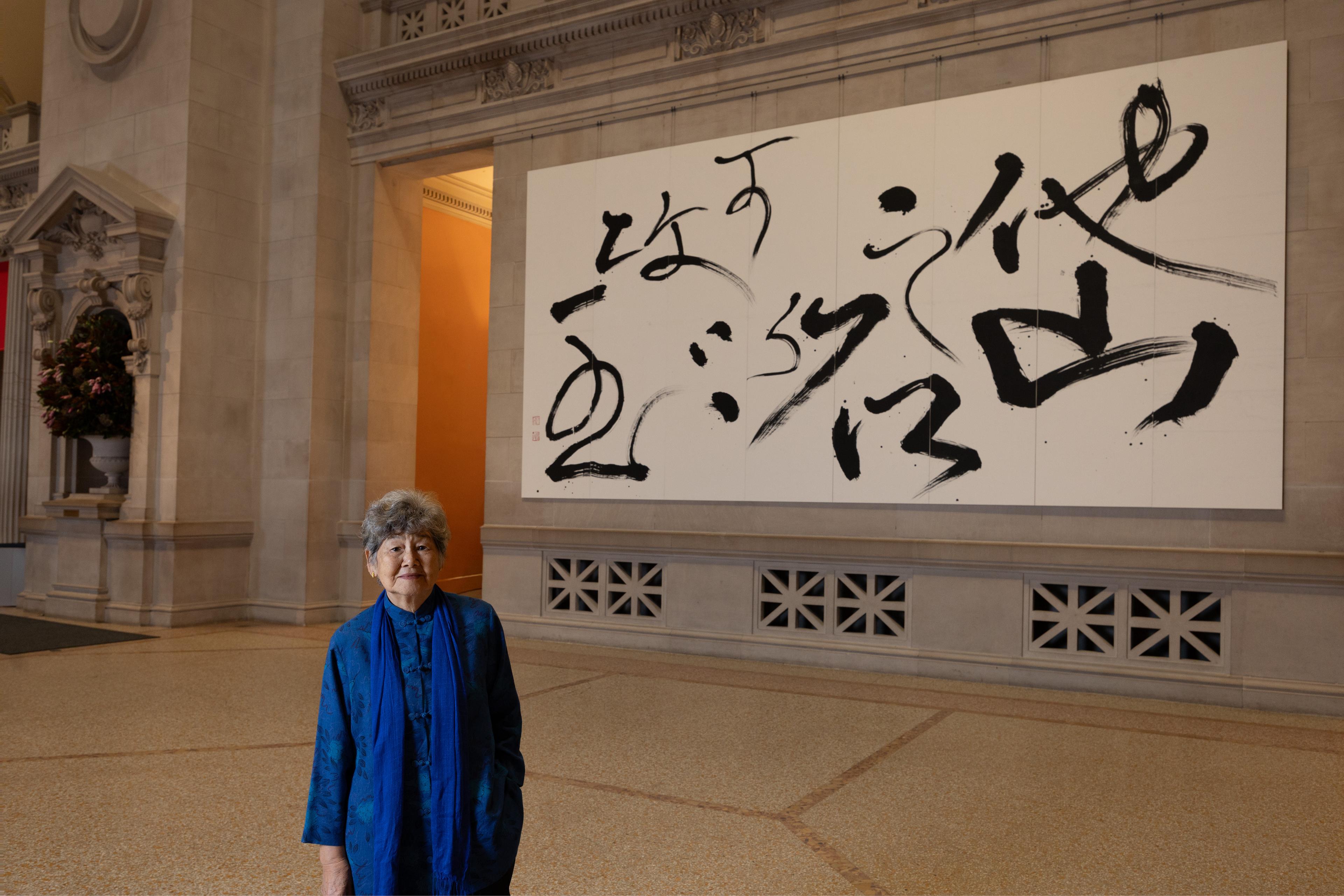

The Met’s Great Hall, with its Beaux-Arts domes and columns in majestic proportions, is where civilizations, art, and people convene. Before The Great Hall Commission began in 2019, contemporary art only had short stints in the space. For the third edition of The Great Hall Commission, in 2024, Taiwanese artist Tong Yang-Tze created two monumental works of Chinese calligraphy for the eastern walls framing the Museum’s entrance.

Contemporary calligraphy in a space that typically displays Egyptian and European sculptures underlines the recent institutional effort to broaden the geographical, conceptual, and material range of art in the public hall. Tong’s calligraphy, in ink on paper, greets visitors with a distinct visual power. As the materiality and idiosyncrasy of calligraphy contrast the printed signages in the neoclassical limestone interior, they highlight the art of writing and text as important areas of historical and contemporary visual culture.

Portrait of Tong in front of her Great Hall commission

Tong is one of the most celebrated artists working exclusively in calligraphy today. Born in Shanghai in 1942, she emigrated with her family to Taiwan in 1952. Having practiced calligraphy since her youth, Tong studied fine art at the National Normal University in Taiwan, whose curriculum included oil painting, ink painting, seal carving, and design. Later, she received her MFA in oil painting in the United States at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Her encounters with Euro-American abstract paintings in the late 1960s and ’70s strengthened her commitment to calligraphy and prompted her to integrate painterly strategies in her work. More specifically, she believed that her ink strokes, with a distinct lineage and purpose in composition, contributed differently to visual language than her counterparts’ gestural marks on canvas paintings. With a strong foundation in the calligraphic style of Yan Zhenqing (709–785), the Tang dynasty scholar-official known for his bold and muscular calligraphy, Tong embarked down her own radical path.

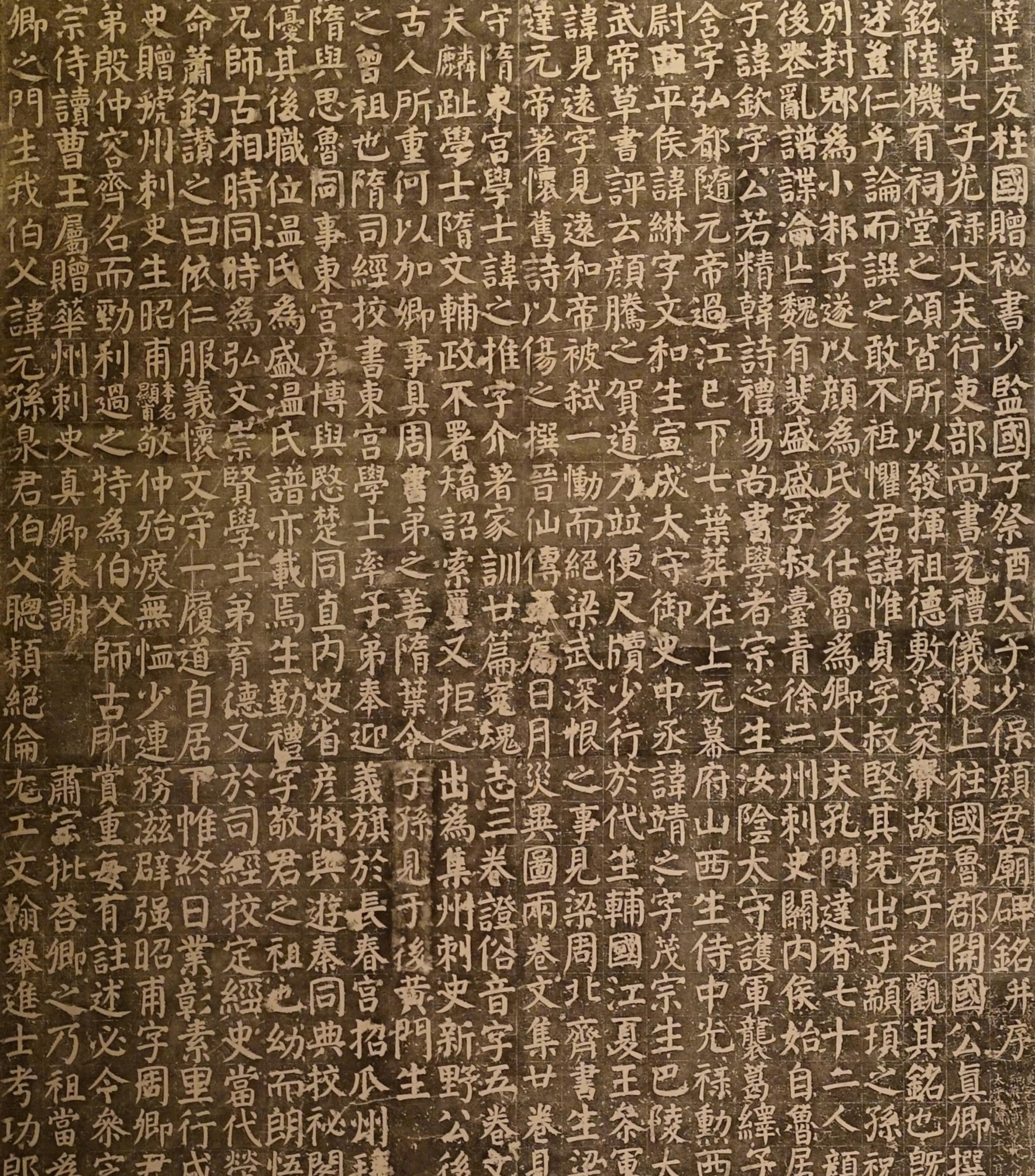

Yan Zhenqing (Chinese, 709–785). Detail of Yan Family Temple Stele 唐 颜真卿 顏家廟碑 現代拓片 紙本, 20th century. 20th-century rubbing of a stele dated 780; ink on paper, 98 x 52 x 1 3/4 in. (248.9 x 132.1 x 4.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Seymour and Rogers Funds, 1977 (1977.375.14a–d)

Following a brief tenure in graphic design in New York City in the 1970s, she returned to Taiwan and came to prominence in the 1980s for her calligraphy, despite its waning influence in contemporary art. By enlarging the scale of her work, engaging with three-dimensional spaces, and drawing inspiration from the monumental size of Euro-American paintings, Tong pushes the conceptual and compositional boundaries of written language as an art form. Using a mix of regular, running, and cursive scripts and altering the characters’ sizes and the ink’s density, she activates the picture through her brushwork. But as she plays with the contours of the individual characters and incorporates painterly strategies, she honors the writing orientation—from top to bottom, right to left—and never deconstructs the Chinese script. The oversized characters create more immediate physical responses to the lines and dots and the materiality of the ink and paper than what traditional formats offer.

While Tong’s calligraphy can be considered part of a generational effort for Chinese artists toward the end of the twentieth century to engage with heritage art forms—including ink painting and calligraphy—on their own terms, hers is a singular force that asserts loyalty to the formal, semantic, and material nature of calligraphy while maintaining its contemporary relevance. The artist’s commitment to writing excerpts from classical texts is driven by a desire to bring the past into the present and to create dialogue with viewers. For her, the practice of calligraphy is not just for self-cultivation but has a social responsibility. In this sense, Tong carries the legacy of artists and intellectuals throughout history who shed light on the human condition through their art.

The practice of calligraphy is not just for self-cultivation but has a social responsibility.

For The Met, Tong chose two of her favorite texts: “Stones from other mountains can refine our jade” from the Book of Odes (ninth and eighth century BCE) was originally interpreted as “talents from another country can be useful to our own.” Over time, the metaphor has come to be understood as “accepting differences can help improve oneself.” “Go where it is right, stop when one must” comes from the words of the poet-scholar Su Shi (1037–1101) and describes his creative process. Today, the phrase is used to encourage self-awareness and moral restraint. Written millennia ago, both texts provide guidance for personal conduct in society; the progressive attitude still holds in the contemporary condition. They are especially appropriate within the museum context, where one’s pursuit and dissemination of knowledge should be grounded in the values of tolerance, diligence, and discipline.

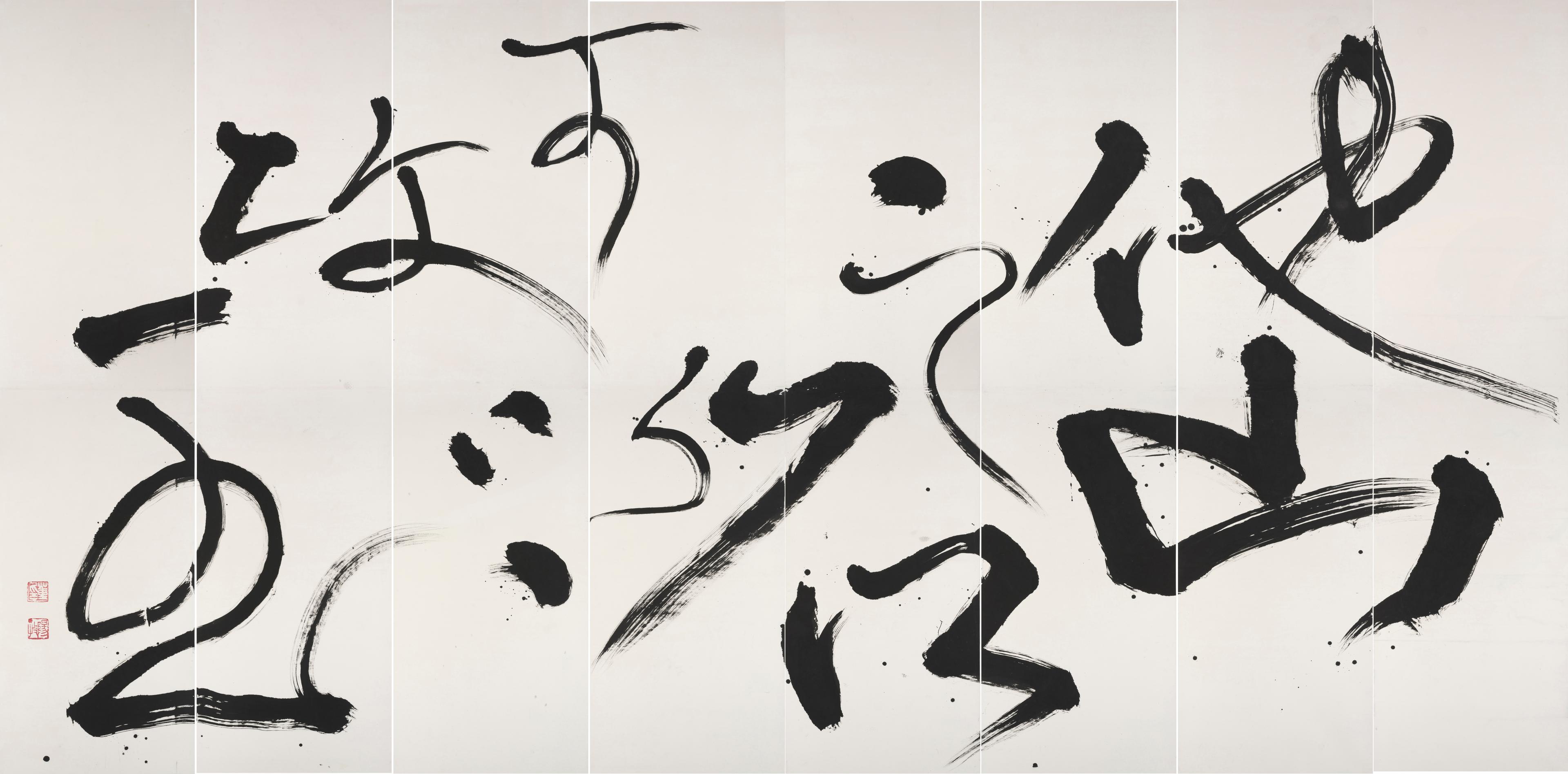

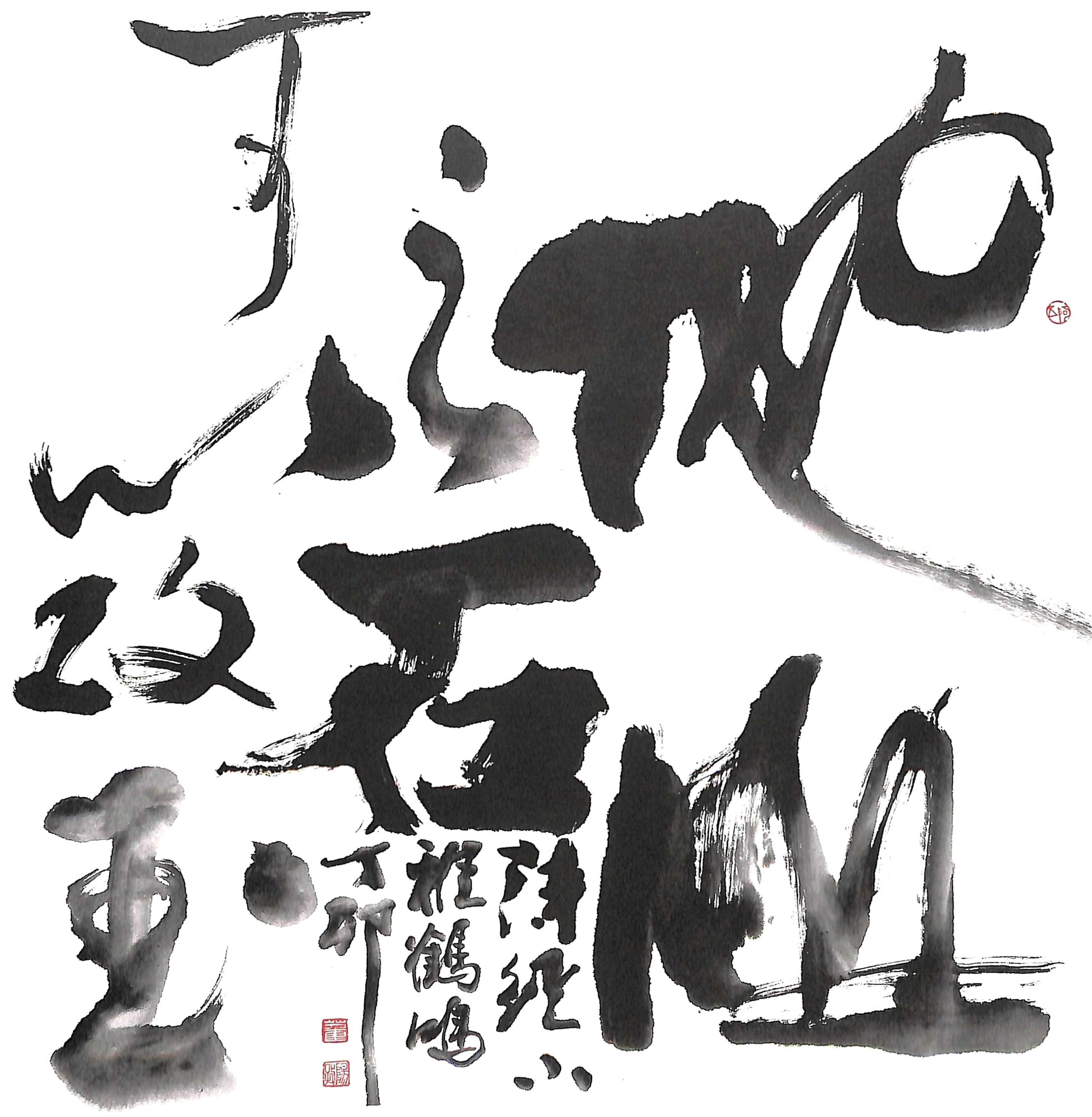

Tong Yang-Tze (born 1942, Shanghai, based in Taipei). Stones from other mountains can refine our jade, 2024. Ink on paper, overall: 360.1 x 726.4 x 2.1 cm. Commissioned by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Courtesy of At Ease Studio

In Stones from other mountains can refine our jade 他山之石可以攻玉 (2024), shan 山 (mountain), shi 石 (stone), and yu 玉 (jade) anchor the composition in thick black ink. Size variations between each character creates a visual rhythm. The occurrences of “flying white” (feibai) indicate the brush’s swift movement and drying ink. Tong throws the last dot in yu 玉 (jade) toward shih 石 (stone) to connect the two characters/objects and to accentuate the action, and sound, of refinement.

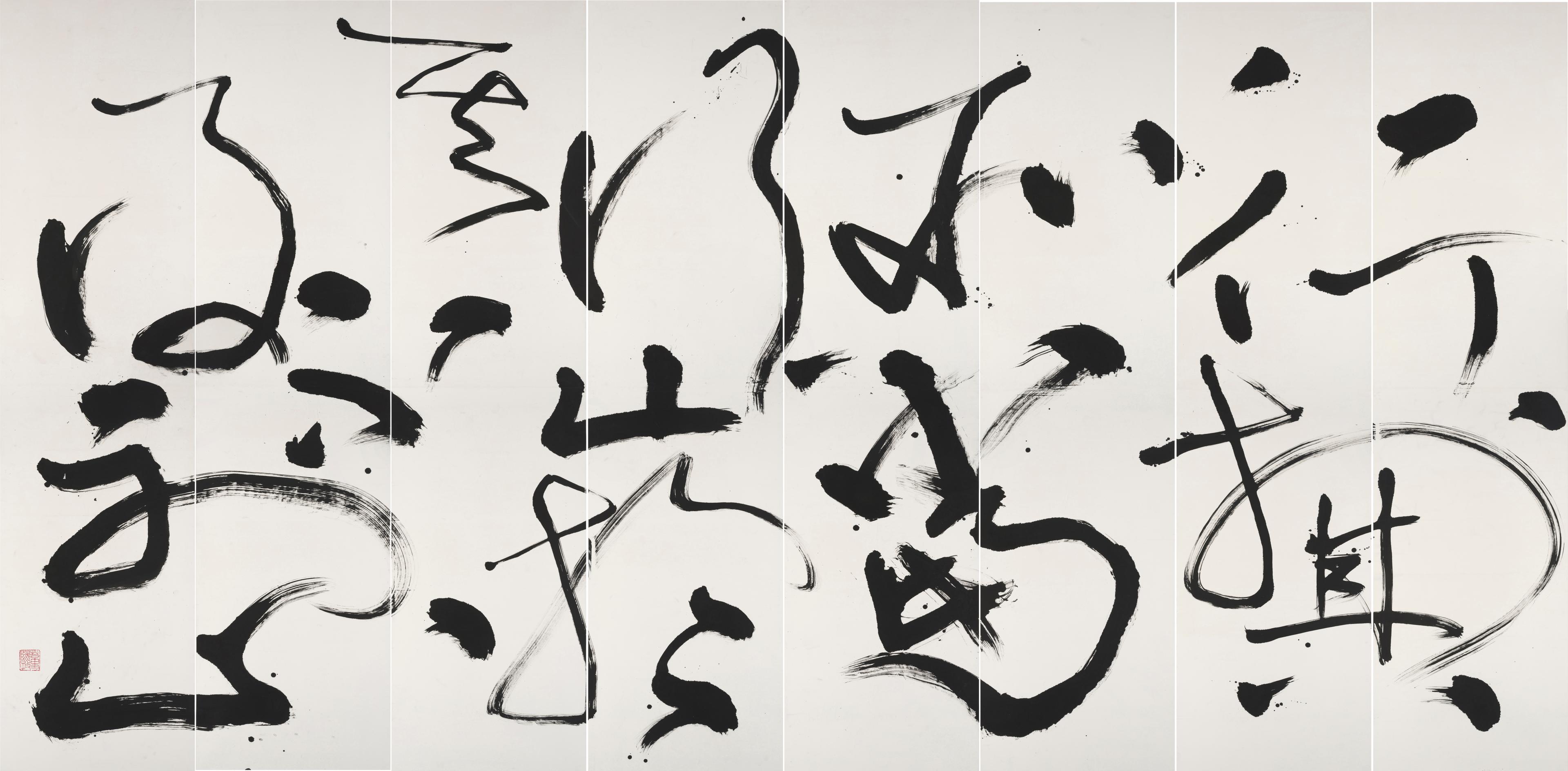

Tong Yang-Tze (born 1942, Shanghai, based in Taipei). Go where it is right, stop when one must, 2024. Ink on paper, overall: 360.1 x 727.2 x 2.1 cm. Commissioned by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Courtesy of At Ease Studio

Go where it is right, stop when one must 行於其所當行,止於其不得不止 (2024) is decidedly more abstract and painterly than the other commissioned work. The thirteen characters in the phrase occupy the whole expanse of the composition. Tong energizes the field of ink marks by interlocking the lines and dots of separate characters and loosening the column-based writing convention. Five characters xing 行 (move forward, go), yu 於 (at, as), qi 其 one (pronoun), zhi 止 (stop), bu 不 (no/not) repeat twice in the text and are each written differently—an act for Tong to challenge herself in composition and convey the sense of freedom and control in the art of writing.

Tong Yang-Tze (born 1942, Shanghai, based in Taipei). Stones from other mountains can refine our jade, 1987. Ink on paper, 27.17 x 27.56 in. (68 x 70 cm). Courtesy of At Ease Studio

Tong had written these two texts before, a practice rooted in the calligraphic training of repetition and her discipline of self-reflection. Each iteration creates an opportunity for new expressions and represents her response to the phrase at that time of her life. The first example of Stones from other mountains can refine our jade, from 1987, was written in watery ink in a square format uncommon in Chinese conventions. Its small scale allows Tong to concentrate on compositional and formal experimentation.

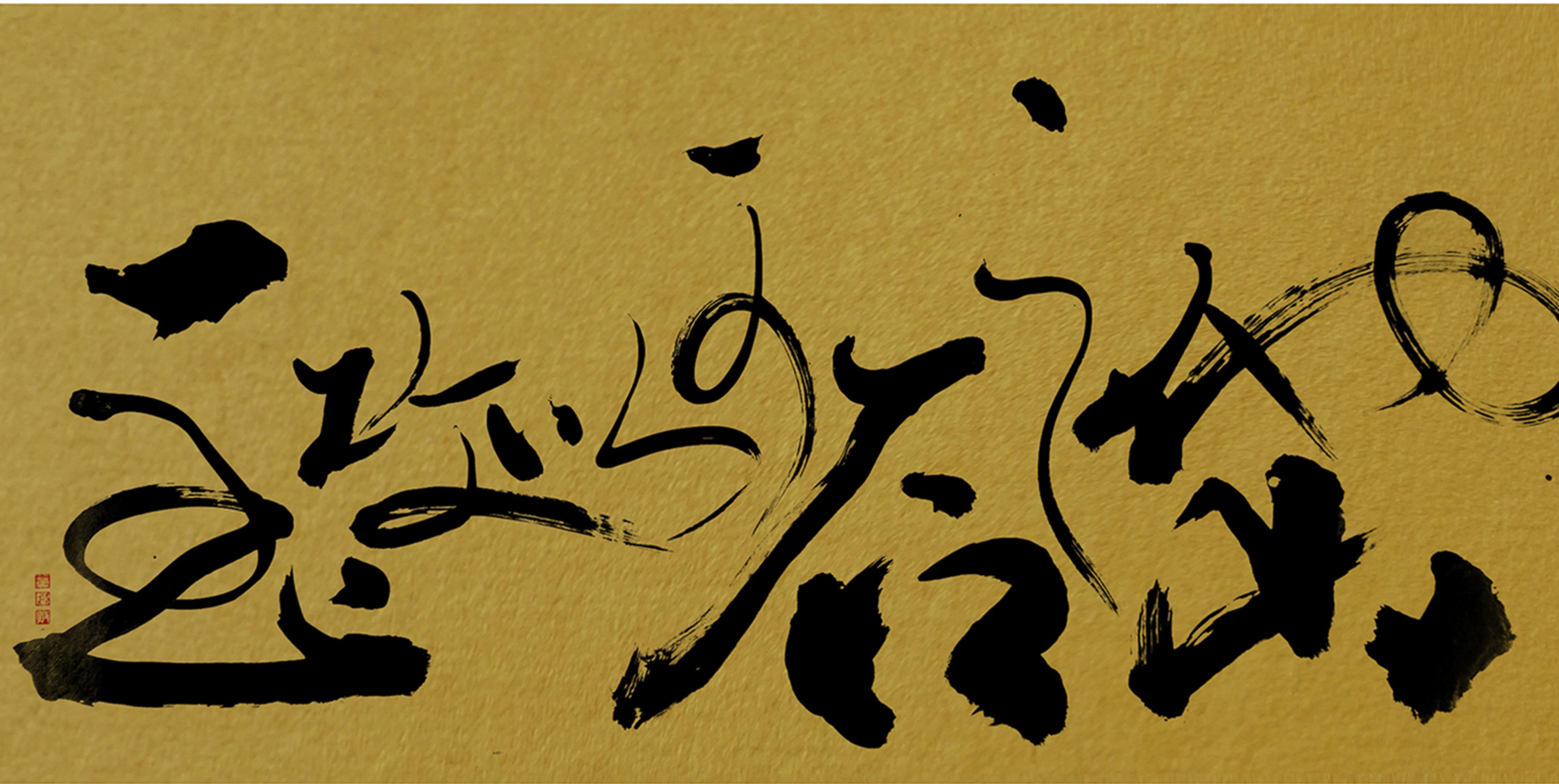

Tong Yang-Tze (born 1942, Shanghai, based in Taipei). Stones from other mountains can refine our jade, 2017. Ink on paper, 27.17 x 54.33 in. (69 x 138 cm). Courtesy of At Ease Studio

In the 2017 version, the eight characters on gold, rectangular paper, flow horizontally, similar to writings on a scroll. The important characters in the phrase are emphasized in dense ink, similar to The Met version, indicating the semantic and visual integration in her work.

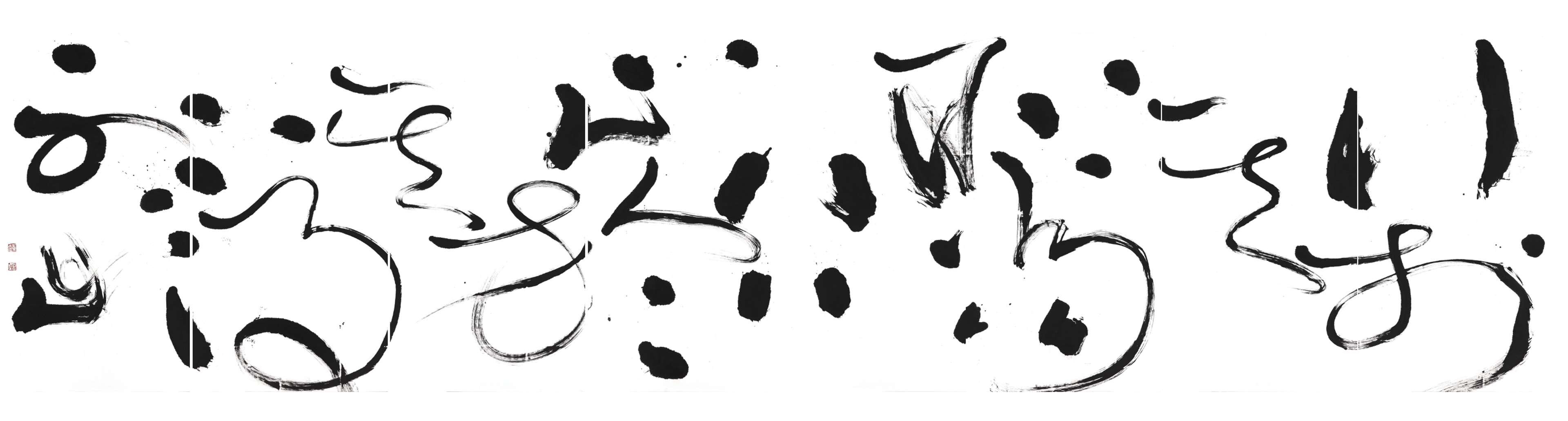

Tong Yang-Tze (born 1942, Shanghai, based in Taipei). Go where it is right, stop when one must, 2006. Ink on paper, 70.4 x 305 in. (179 x 776 cm). Courtesy of At Ease Studio

The characters in the 2006 version of Go where it is right, stop when one must form a horizontal staccato with dot-like strokes that showcase Tong’s ability to manipulate the characters based on layout and syntax. Though in different proportions, The Met commissions and the works of the same texts are consistent in their bold, forceful lines and rhythmic energy. But The Met pieces were written in a blend of regular and running scripts, more legible than the cursive script that she employed in the others, to ensure the works in a public space like the Great Hall are more reader friendly.

Calligraphy combines linguistic and expressive content in simple, organic materials, a quality that has remained unchanged for hundreds of years. Tong’s innovation is in magnifying the movement and dynamism of the lines, expanding the compositional possibilities, and creating a physical relationship between the body and the ink. Within the Museum’s collection, her work speaks to the tradition of the art of writing in the historical holdings in Asian Art and Islamic Art departments. In the context of the twentieth- and twenty-first century, her work is in the lineage of East Asian artists such as Shen Yinmo and Inoue Yuichi who believed in calligraphy’s capacity in expressing radical politics, complex emotions, and modernist beliefs, as well as in the discourse of conceptual artists like Xu Bing, Qiu Zhijie, and Gu Wenda, who deconstructs the system of knowledge through calligraphy- or script-based projects.

Installation view of Tong Yang-Tze's 2024 Great Hall Commission

At the same time, her calligraphy inspires new conversations with works by Mark Tobey, Franz Kline, Helen Frankenthaler, Julie Mehretu, and Siah Armajani in terms of scale, composition, and mark-making. Each of these artists expressed their lines in the pictorial space to explore ways of expanding the language of painting and storytelling. Tong’s work combines linguistic, compositional, literary, spatial, and social concerns through the most basic material and action—writing in ink on paper—that provides a counterpoint to these painterly endeavors. Within this long, fascinating history of lines and text in visual culture, Tong’s work offers new connections at the beginning of one’s journey at The Met—the Great Hall.