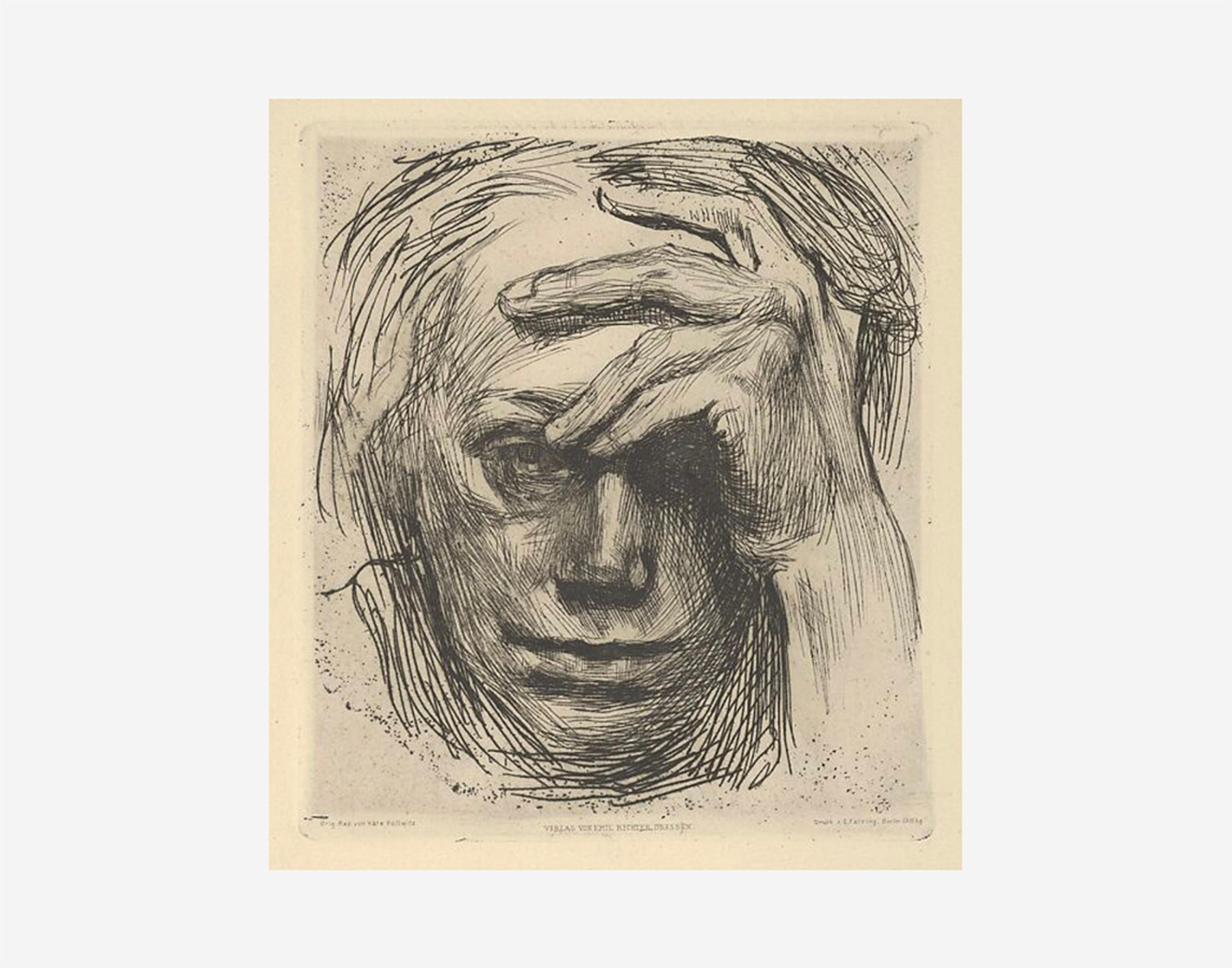

Käthe Kollwitz (German, 1867–1945). Self-Portrait with Hand on the Forehead (Selbstbildnis mit der Hand an der Stirn), 1910. Etching and drypoint, image: 6 x 5 1/4 in. (15.2 x 13.3 cm), sheet: 17 5/8 x 12 1/4 in. (44.8 x 31.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Leo Wallerstein, 1942 (42.30.17)

It was the first time I had seen the world through a grown woman's eyes.

My name is Natalie Frank and I’m a painter.

Kollwitz was the first artist who I was introduced to. I read a lot as a child and all of the literature seemed to be from the vantage point of men. It was the first time I had seen the world through a grown woman’s eyes.

For instance, the image of The Rape is definitely by a woman. How she’s lying, you can feel the weight of her body, the weight of her leg—her thick, muscular thighs—the weight of her head. Her arms are bound behind her. Her legs are splayed open. There’s a little girl in the back looking down on the scene. So it’s purely a domain of women. A man has obviously been there, but this is, to my mind, one of the first representations of sexual violence towards a woman, from the vantage point of a woman.

That’s what I get from Kollwitz. It’s empathy. The images of young women and their husbands, or even a woman and herself: you feel the weight of what it feels like to be a woman.

Her physical presence and her autobiography is everywhere in her work, and it is so pure and intense and unguarded. And as a young person trying to figure out what you want to make work about, what your story is, the bravery to do that is compelling.

I coveted a lot of her skills that I didn’t feel I had. She is an incredible draftsman, and I was always drawn to paint and color. She put together figures like she was grappling, trying to show something interior, and at the same time there was mastery. It came out as a complete idea, perfectly laid out. And in printmaking that’s incredibly difficult, because there’s no erasing: once you’ve taken something away you can’t put it back. It’s also printed in the reverse, and to have that kind of foresight and control was incredible to me.

It hasn’t been that long since Kollwitz made these images. A lot has changed but a lot hasn’t changed. Women are still unheard. And so for that reason Kollwitz resonates. She’s a feminist. She was making very avant-garde images at a time when women were still kept out of schools. But she took so much from her life and her surroundings and made it into something that gave her access. And she was recognized in her life and celebrated.

In everything she did you felt her politics and her sincerity and her belief in herself and the power of her own narrative. She’s someone I’m constantly thinking about, who’s ever-present in how I see the world, because of how daring her work is.