Women’s work. Once used as a demeaning term for household labor, when applied to art-making, it expands considerations of why we express ourselves and recognizes the tremendous contributions women have consistently made to art history across time.

As part of The Met’s celebration of Women’s History Month, we asked a selection of contemporary women artists with work in the collection to reflect on their art and to share what inspires them most in the Museum. In this first installment of our two-part series of discussions, Qualeasha Wood speaks to the navigation of interior and exterior spaces in her tapestry, The [Black] Madonna/Whore Complex (2021). Amy Sillman discusses the time she commits to finding form for works like Finger x 2 (2015). And Pat Steir shares the excitement of discovery that resulted in Sixteen Waterfalls of Dreams, Memories, and Sentiment (1990) and the thirty-three years of art-making that followed.

Qualeasha Wood

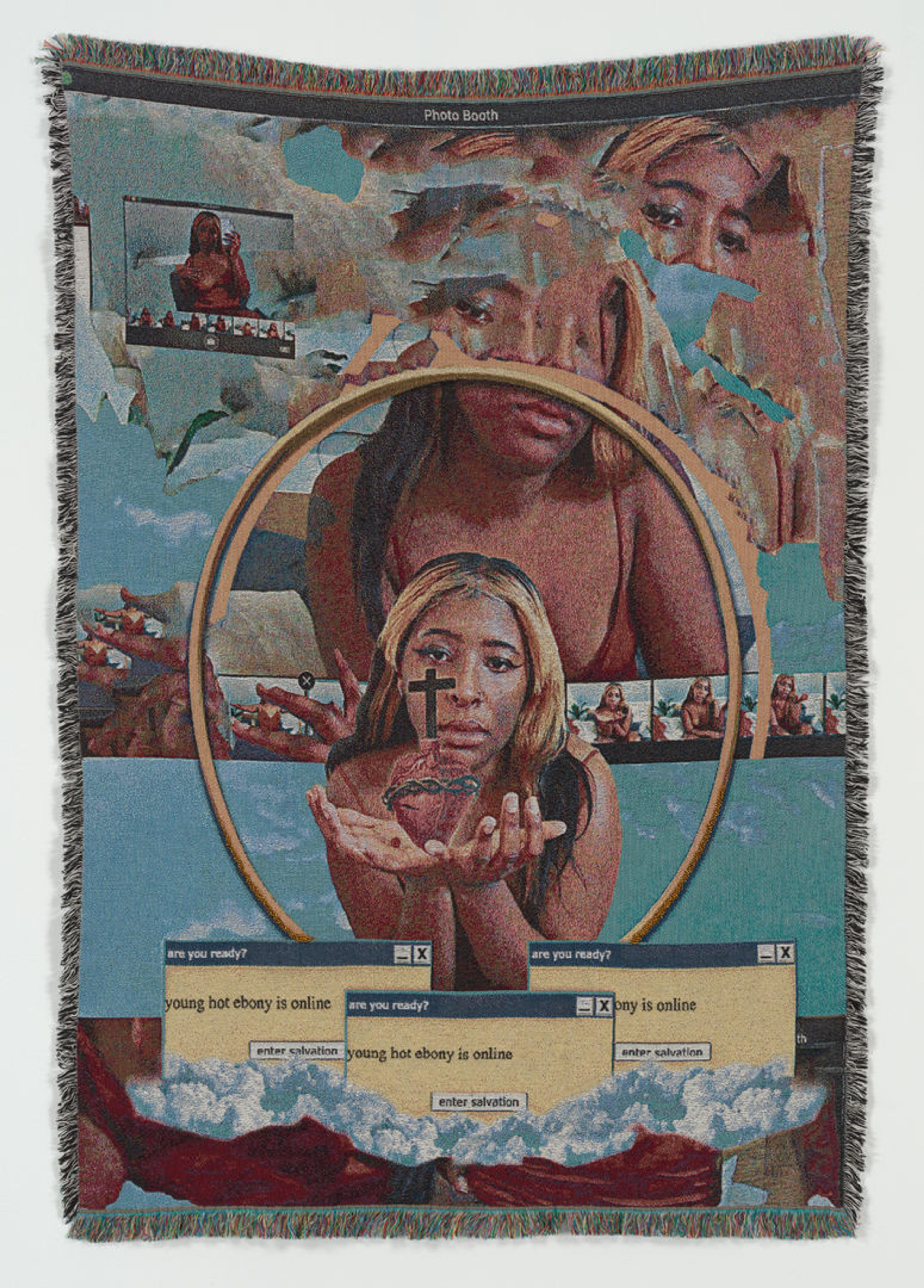

Qualeasha Wood (American, 1996). The [Black] Madonna/Whore Complex, 2021. Jacquard-woven cotton, glass beads, 71 × 54 × 1/2 in. (180 × 137 × 1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Funds from various donors, in memory of Randie Malinsky, 2022 (2022.51) © Qualeasha Wood, courtesy of the artist and Gallery Kendra Jayne Patrick, New York

Is there anything you would like readers to know about The [Black] Madonna/Whore Complex?

There’s something really fun about the tapestries that feels like unwrapping a gift. Each time you look, you recognize something new. I enjoy watching people point at and dissect different things going on in the piece and pulling out what they recognize. There is an overlapping of space, a barrier being broken, that happens a lot as the work navigates interior and exterior spaces. On the one hand we’re dealing with the digital, which implies the future, but we’re also dealing with the present moment and the past through the physical moments being depicted. There are parts of my old home in there, the bed I used to have, even plants that are no longer living. This blurring of worlds is one of my favorite things about the piece.

“The studio for me exists in the bedroom, at home, as much as it exists in the professionally zoned places we might pay to create in, too.”

– Qualeasha Wood

There’s an assumption that I do a lot of the work in a professional studio environment, but the studio for me exists in the bedroom, at home, as much as it exists in the professionally zoned places we might pay to create in, too. I invite people to look and to look closely for what is there on the surface but also to consider what is lost or hidden. There are over one hundred layers that went into the creation of this piece, in its digital version, but what we’re left with is what comes together.

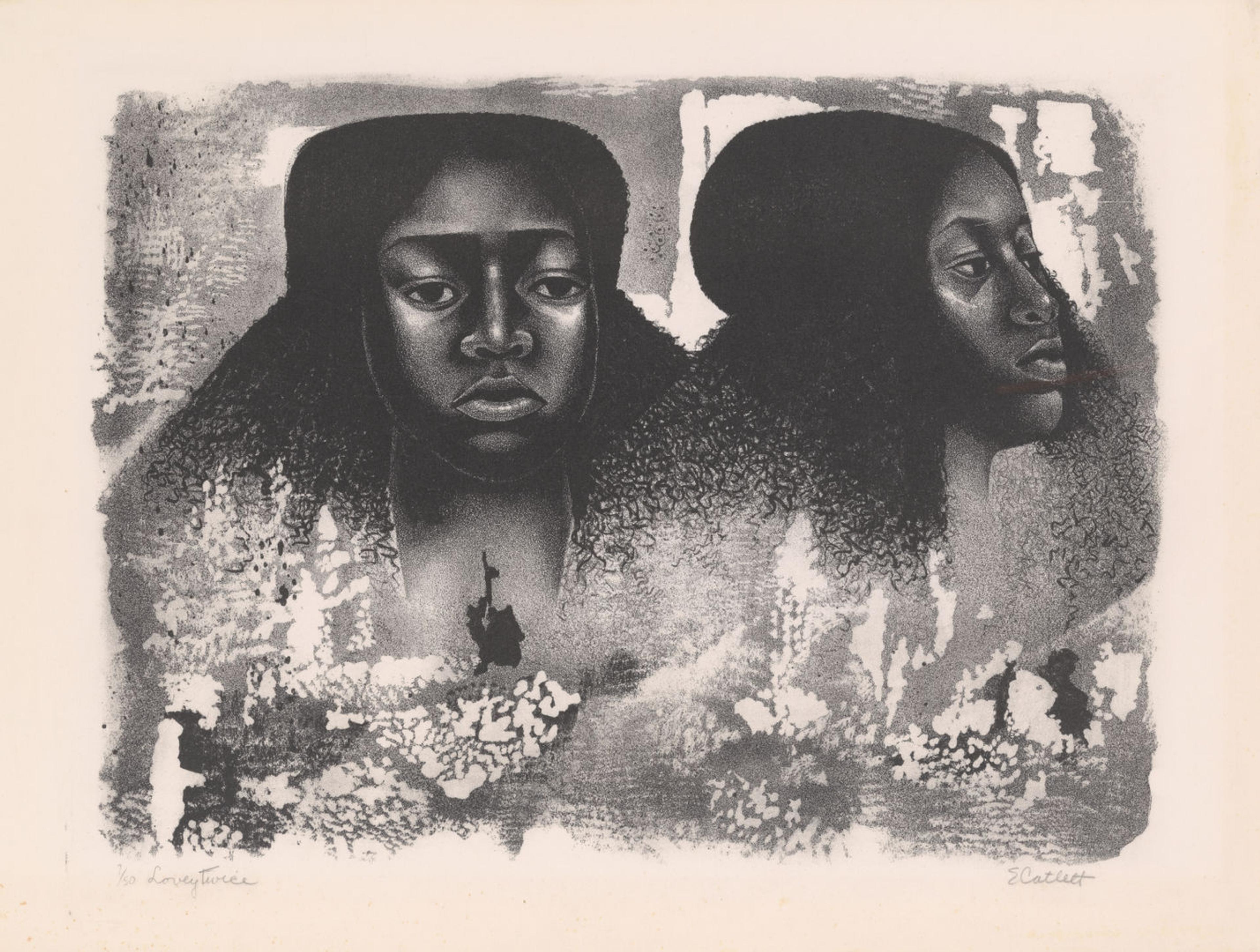

Elizabeth Catlett (American and Mexican, 1915–2012). Lovey Twice, 1976. Lithograph, Image: 15 3/4 × 21 1/4 in. (40 × 54 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Purchase, Bertha and Isaac Liberman Foundation, 2021 (2021.98)

Are there works at The Met you regularly turn to when you visit?

I always look for certain artists or things at the beginning of my journey in any museum, and I visit the prints and textiles most often. Elizabeth Catlett is someone I look for everywhere, and Lovey Twice (1976) is a piece I’ve returned to visit quite a few times. It challenges what it means to be looking and seeing, which is something important in my work right now. As someone who started falling in love with art through lithography, it’s a reminder of my journey.

Amy Sillman

Amy Sillman (American, 1955). Finger x 2, 2015. Oil on canvas, 75 × 66 in. (191 × 168 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Purchase, Edith C. Blum Fund, and Andrew J. and Christine C. Hall Foundation Gift, 2016 (2016.694) © Amy Sillman

Is there anything you would like readers to know about Finger x 2?

It takes me a long time to construct my paintings, because they are all made through a seemingly endless process of drawing, revision, wiping out, and rebuilding in order to find their form. Each has its own path, and this group of paintings started with ideas about hands, as tools in part. But then, as they always do, it went on its own path to become an abstract painting, something built out of parts. So it’s not a “finger” when it starts out... but I have to name them in a very pragmatic way, so I can refer to them and remember which is which (and not always just say Untitled # this, and Untitled # that...). So it became Finger only as a kind of mnemonic designation, and Finger x 2 because there was apparently a first “finger”!

Are there works at The Met you regularly turn to when you visit?

Are you kidding? The list is way, WAY too long! The whole Museum has spoken to me and helped me think through my own work and thoughts for almost fifty years. It’s a well-worn art history book on the shelf of my mind.

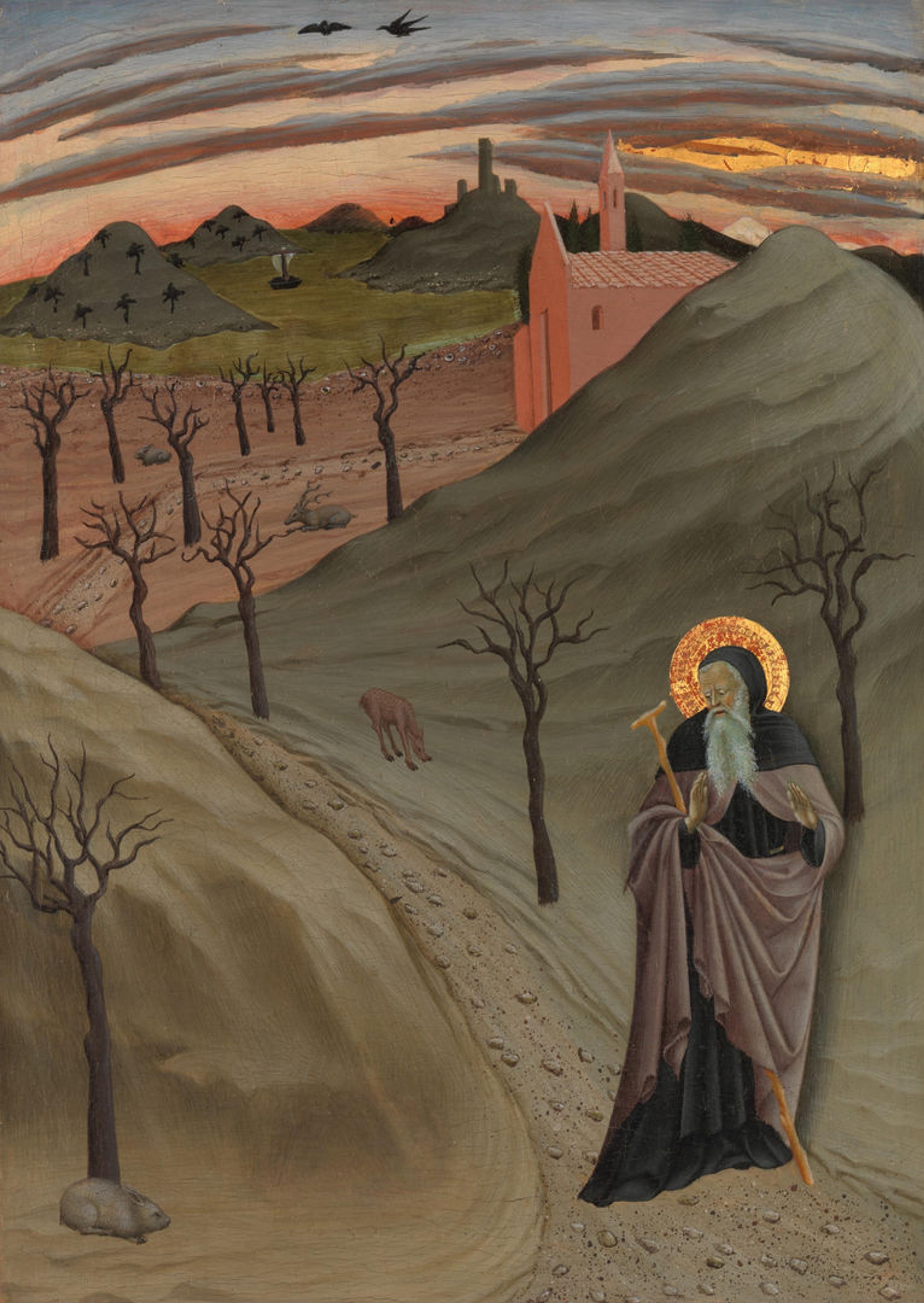

Osservanza Master (Italian, active second quarter 15th century). Saint Anthony the Abbot in the Wilderness, ca. 1435. Tempera and gold on wood, 18 3/4 x 13 5/8 in. (48 x 35 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.27)

One little tiny one that I always used to love visiting, simply because I was often with someone who hadn't seen it and I wanted to show it to them, is an unassuming painting in the Robert Lehman Collection, called Saint Anthony the Abbot in the Wilderness (ca. 1435), by the Osservanza Master. But I also just walk through every time and see everything again and again and again.

Pat Steir

Pat Steir (American, 1940).Sixteen Waterfalls of Dreams, Memories, and Sentiment,1990. Oil on canvas, 78 1/2 in. × 12 ft. 7 1/8 in. (199 × 384 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Kathryn E. Hurd Fund, by exchange, 2009 (2009.473) © Pat Steir, New York, NY

Is there anything you would like readers to know about Sixteen Waterfalls of Dreams, Memories, and Sentiment?

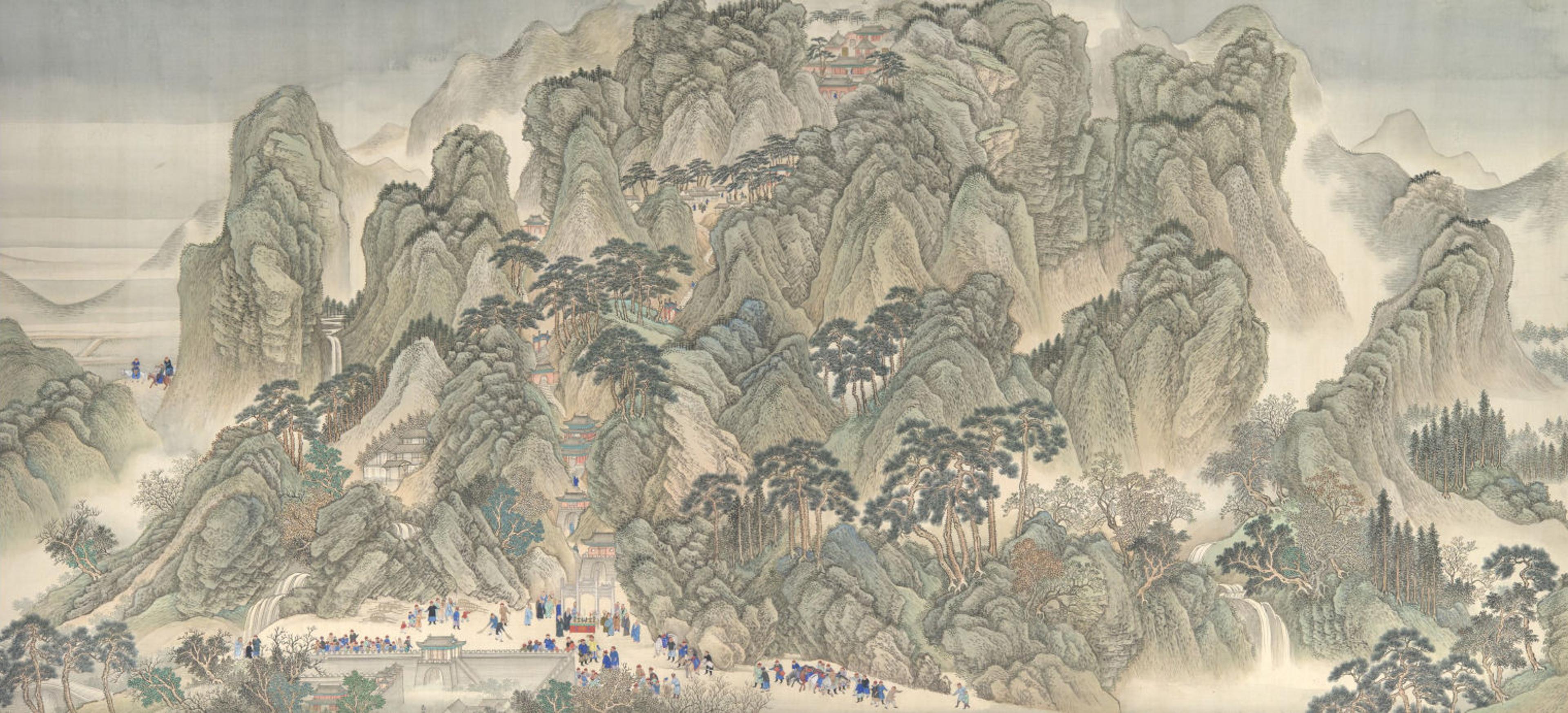

I was searching for an image that could be abstract, minimal, and figurative at once. At the same time, I was reading about historic Chinese painting, especially Song dynasty pottery glazes and literati landscape painting. I met John Cage; I was very impressed by his thinking and the outcome in his work. I decided to simply make one mark and let the paint flow its own way, allowing the paint to make its own picture. Seemingly out of the blue, there was Sixteen Waterfalls of Dreams, Memories, and Sentiment, the first fully realized painting in a thirty-three-year series.

Are there works at The Met you regularly turn to when you visit?

In the Asian art collection, I study Chinese, Japanese, and Korean art and objects, the Buddha sculptures, and calligraphy. I always go to the African and Oceanic wings. I particularly love the little Mangaaka power figure from the Congo who once guarded his town and for years stood at the entrance to the African wing.

Wang Hui (Chinese, 1632–1717, and assistants). The Kangxi Emperor's Southern Inspection Tour, Scroll Three: Ji'nan to Mount Tai, datable to 1698. Handscroll; ink and color on silk, Image: 26 3/4 in. x 45 ft. 8 3/4 in. (68 x 1394 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Purchase, The Dillon Fund Gift, 1979 (1979.5a–d)

I go to The Met at least once a month, and I am influenced by almost everything I see. Sometimes it’s a color, sometimes it’s a form, possibly a Greek vase that I never noticed before, a cast gold piece, a fabric. Maybe it’s a small detail, like the color of a rose on a carpet in a painting.