The secret lives of artworks

Artworks enter The Met collection in a variety of conditions. The passage of time takes its toll, but sometimes they’ve survived even more—unique odysseys not evident to the public. Here, dig deeper into three conservation stories that reveal the hidden lives of artworks.

One witnessed dramatic encounters in ancient Egypt. Another once lived in the atelier of a deceased French artist. The third owes its life to the marvels of 3-D–printing. Whether they were broken, recast, or prototyped, ancient or contemporary, these objects each hold remarkable stories. Read on to learn how Met conservators help divulge these and more, and keep the objects safe for future generations.

Life after destruction

Different restoration techniques across the decades impact how visitors have seen Hatshepsut. Left to right: head of the statue of Hatshepsut in 1929; after 1930 restoration; after 1979 restoration; after 1993 restoration

What does it mean to stand the tests of time? This seated statue of the powerful ancient Egyptian pharaoh, Hatshepsut, dates to the fifteenth century B.C., when it was carved for her funerary temple. After her death, her successor shattered the statue in effort to obliterate her memory. Instead, her legacy prevails, thanks in part to the work of multiple conservators at The Met.

It wasn’t a simple task. Since the statue arrived in New York, it has undergone three major restorations. The first took place in the 1930s, when conservators followed what was then considered best practice; they joined every fragment and filled the cracks with plaster until Hatshepsut appeared almost whole, less battered by time.

Later, in 1979, conservators wanted to distinguish the restored surfaces from the original, so they replaced the previously treated areas with recessed, textured fills of a slightly different color. The goal of this approach was to preserve evidence of age and weathering, and to respect the integrity of what remained of the original object.

The most recent restoration, in 1993, drew on the strengths of both prior treatment campaigns, with restoration reserved only for the most visible and distracting losses on the face. You can see this in the left eye, which was restored by using an inverted cast of the right eye. Today, with early restoration mitigated by modern conservation, we can better appreciate the statue’s full beauty and grandeur.

A tutu for all time

Trace the different skirts Degas’s Dancer has worn over time. Left to right: original skirt made in 1922; replacement skirt made in 1968; 1998 replica of an early skirt for a bronze cast; 2018 tutu based on the original wax sculpture

You’ve heard of clothing described as “timeless,” but Edgar Degas’s sculpture The Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer embodies the idea in an unusual way. Consider its evolution.

When the original version of the sculpture was first exhibited in 1881, Degas incorporated a mix of unorthodox materials: human hair, a cotton bodice, linen ballet slippers, and a tutu made of tarlatan, a kind of open-weave cotton. In particular, tinted beeswax used for the skin gave the figure an uncanny appearance. Upon Degas’s death in 1917, his heirs decided to cast some of his sculptures, including the Little Dancer, in long-lasting bronze. Her skirt, along with the silk hair ribbon, were the only parts not cast into bronze.

Since the arrival of the bronze cast at The Met in 1929, the skirt has been replaced three times.

Glenn Petersen, conservator in the Costume Institute, took on the challenge most recently in 2018. He began by researching typical ballet costumes of the era. This meant the skirt should be knee length and made of materials similar to the heavily starched, cotton tarlatan used at the time. He also avoided recreating its original color, aware that an immaculate white fabric would appear harsh against the time-worn bronze.

Instead, he chose a color that would suggest white cloth that had aged naturally over time, and he airbrushed on some darker tones. Today, The Met’s bronze sculpture wears the skirt Petersen crafted in 2018 and the style, materials, and color of the skirt blend into a harmonious whole.

Next in fashion, and conservation

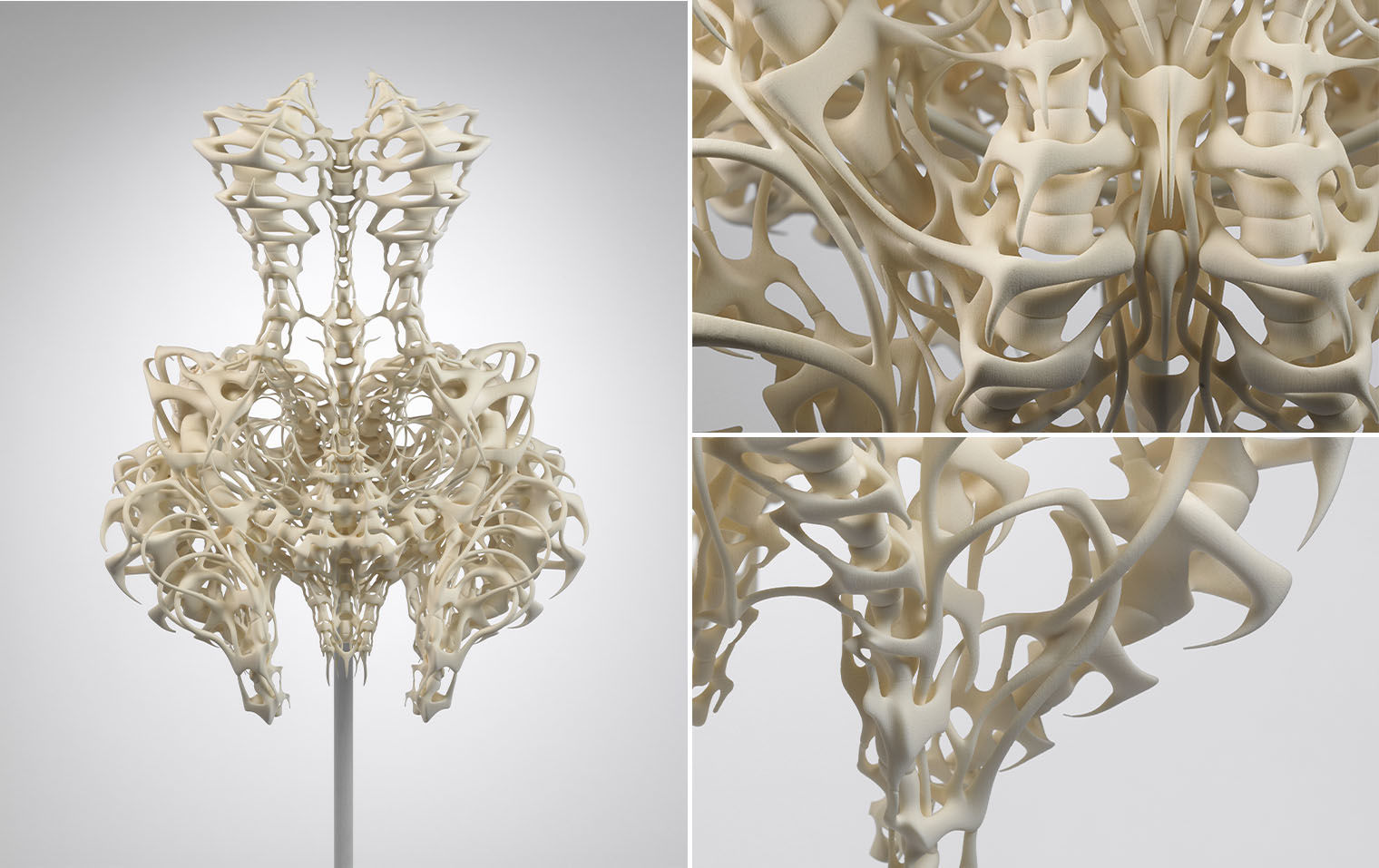

Close-ups of Van Herpen's Ensemble, or “Skeleton”, reveal the dress's granular surface

Striking, yes. Ordinary? Not so much. Iris Van Herpen’s 3-D–printed Ensemble, also known as “Skeleton,” arrived at The Met’s Costume Institute in 2015. Unlike fabric that folds and adapts to the wearer’s movements, this rigid nylon carapace forms a shell-like covering that doesn’t yield to a moving body. The dress upends traditional ideas, not just of what clothing can be and how it can be made, but also how best to preserve it.

Even in the past eight years, the physical condition of “Skeleton” reflects significant deterioration. The nylon is now an off-white color, its porous surface is accumulating significant dust, and a few delicate protrusions show significant losses.

The 3-D–printing process for nylon is to blame. It’s a method of printing devised for prototypes with a short life-span. A laser fuses powdered nylon in a nitrogen-filled environment. The nylon powder, spread on a building platform, is fused into a computer-generated shape. A subsequent layer of nylon powder is applied, and the process is repeated as the laser builds the object layer by layer. These sustained high temperatures, paired with the fact that sometimes leftover nylon powder is reused and reheated in other builds, means that the polymer is already degraded once it fuses into a 3-D–printed object. This is what has caused the dress to yellow and become brittle so quickly.

Some artworks surface new ideas, others new challenges to be addressed. When “Skeleton” arrived at The Met, it did both; conservators had not yet established best practices for the preservation of 3-D–printed objects. Today, its unique materiality is a reminder that just as artworks evolve, so must the conservation techniques required to preserve them. Research is now underway on the long-term preservation of plastics, spurring conservators to build on their already strong scientific foundations to find methods to sustain artwork for another 150 years and beyond.