A wide array of percussion instruments occupied The Met Cloisters’ many crevices when composer Michael Gordon’s work The Forest of Metal Objects premiered on Friday, June 27, 2025. A range of cymbals high, medium, and low. Several deep gongs. Ever more cowbells. Vibraphones, stricken with their yarn-wound mallets until their sounds blended into a velvety wash.

From there, the instruments got more esoteric. Hardware-store flower pots, tapped with vibraphone mallets. Specially tuned aluminum sheets, scrounged from a Michigan scrap-metal shop. Lengths of chain, dangled and rattled. A new instrument fashioned from steel concrete-reinforcement bars, cut to size and suspended such that they could almost muster a tune when played in sequence.

Members of the University of Michigan Percussion Ensemble in the Cuxa Cloister. © Stephanie Berger

Together with six silent actors, the sixteen percussionists of The Forest of Metal Objects moved steadily through the Cloisters’ galleries, creating an all-enveloping, indoor-outdoor experience that culminated in the central Cuxa Cloister. Gordon tapped iconic downtown avant-garde couple Annie-B Parson and Paul Lazar to fuse the procession’s movement with its music—a marriage that forms one of the stated missions of Big Dance Theatre, which the duo founded in 1991 and co-directs to this day. With text-based art by Todd Colby and costumes by Colby and Liv Rigdon, the piece is an apt sequel of sorts to Gordon’s meditative Field of Vision, which I experienced in the University of Michigan Percussion Ensemble’s highly choreographed performance at Brooklyn’s Fort Greene Park in 2023. (The ensemble, directed by Doug Perkins, also gave The Forest of Metal Objects’ premiere.)

Ahead of the premiere, I spoke on separate occasions with Parson/Lazar and Gordon about their maiden collaboration—and how The Met Cloisters inspired it. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for publication.

Emery Kerekes:

Take me back to the inspiration and inception behind this piece. What were those first concept meetings like?

Michael Gordon:

When you live in New York City, The Met Cloisters is almost like a magic castle on a hill—it's almost mythic. There is no other place like this in the city. So when MetLiveArts commissioned me, I wanted to use the environment.

The Met Cloisters seen from the surrounding Fort Tryon Park.

Paul Lazar:

I only remember that Michael explained that he’s making a percussion piece with sixteen University of Michigan percussionists. We immediately had the association of having seen Field of Vision, for thirty-six Michigan percussionists, at MASS MoCA.

We had a feeling for the kind of work Michael was envisioning, but he wanted to add a dance/theater component to it. It was much more open of an idea than somebody asking me to direct Death of a Salesman, or asking Annie-B to restage one of her dances. But we’re so attracted to Michael’s music, and though he’s very particular about what we’re up to, he’s paradoxically quite open as to the way we want to grapple with it. So it's a very open invitation. You might say it was unspecific: “I want you guys to be part of this.”

Gordon:

I came to the Cloisters with Paul four or five times. Of course, it would be a dream to fill every gallery and garden and cloister with activity, but we’d probably need several hundred people. It's all a question of narrowing it down, a process of limiting yourself and going, “Oh, we can work here. We can work there.”

Kerekes:

Why percussion? Why now?

Gordon:

I love percussion because it’s so wide open—the sound world is basically limitless. A lot of musical genres have a very defined sound world. A band, an orchestra, even a Balinese gamelan ensemble: we know what that sounds like. But a percussion ensemble can be almost anything, and it’s a place you can go to search for a new sound. It’s the same way that people have for hundreds of years experimented and figured out the limits of instruments. What can the piano do? The violin?

A percussion ensemble can be almost anything, and it’s a place you can go to search for a new sound. It’s the same way that people have for hundreds of years experimented and figured out the limits of instruments.

The music director on this project is the great percussionist Doug Perkins. I’ve been fortunate to work with Doug on many other projects—he just brings this spirit of “whatever it is, we're going to do it.” Yes, we’re going to get this junk metal and cut it and tune it in this very specific and novel way. Part of that process has been hands-on. I spent an afternoon going to probably the craziest metal shop in Detroit, Michigan, filled with huge metal sheets and planks. And we took sticks and we banged on everything, searching for sounds. The process is part workshop, part exploration, part experimentation.

And, you know, we think about percussion, and sometimes people go, "Oh, loud, right?” But percussion doesn’t have to be loud. It actually can just be beautiful and reverberant—and, in this case, metallic and shimmering. So there are all kinds of dimensions here that we can be, you know, exploring.

Kerekes:

In addition to sixteen percussionists, The Forest of Metal Objects also includes six silent actors. How do you conceive of this piece’s theatrical world?

Actors in performance in the Langon Chapel. © Stephanie Berger

Lazar:

The piece is not anything like a play. It’s more about finding a reality that augments the musical experience, one that is sustainable and understood and shared between the performers.

Annie-B Parson:

In this case, Paul’s and my ideas stem both from the materiality of the music—that a lot of it is made of found objects—and from the Cloisters’ particular architecture. How does that architecture inform the staging? How can you animate the architecture itself? What can the architecture do to the physical ideas now that we actually are in the midst of extraordinary, very old artworks derived from religious seekers or people that are contemplating spiritual ideas?

So we first sort our process physically. Where will the audience enter? Where could the musicians be? The actors? What’s interesting and alive and simple? It could be stillness, it could be slowness, it could be something that’s kinetic. But it needs to be musical.

Lazar:

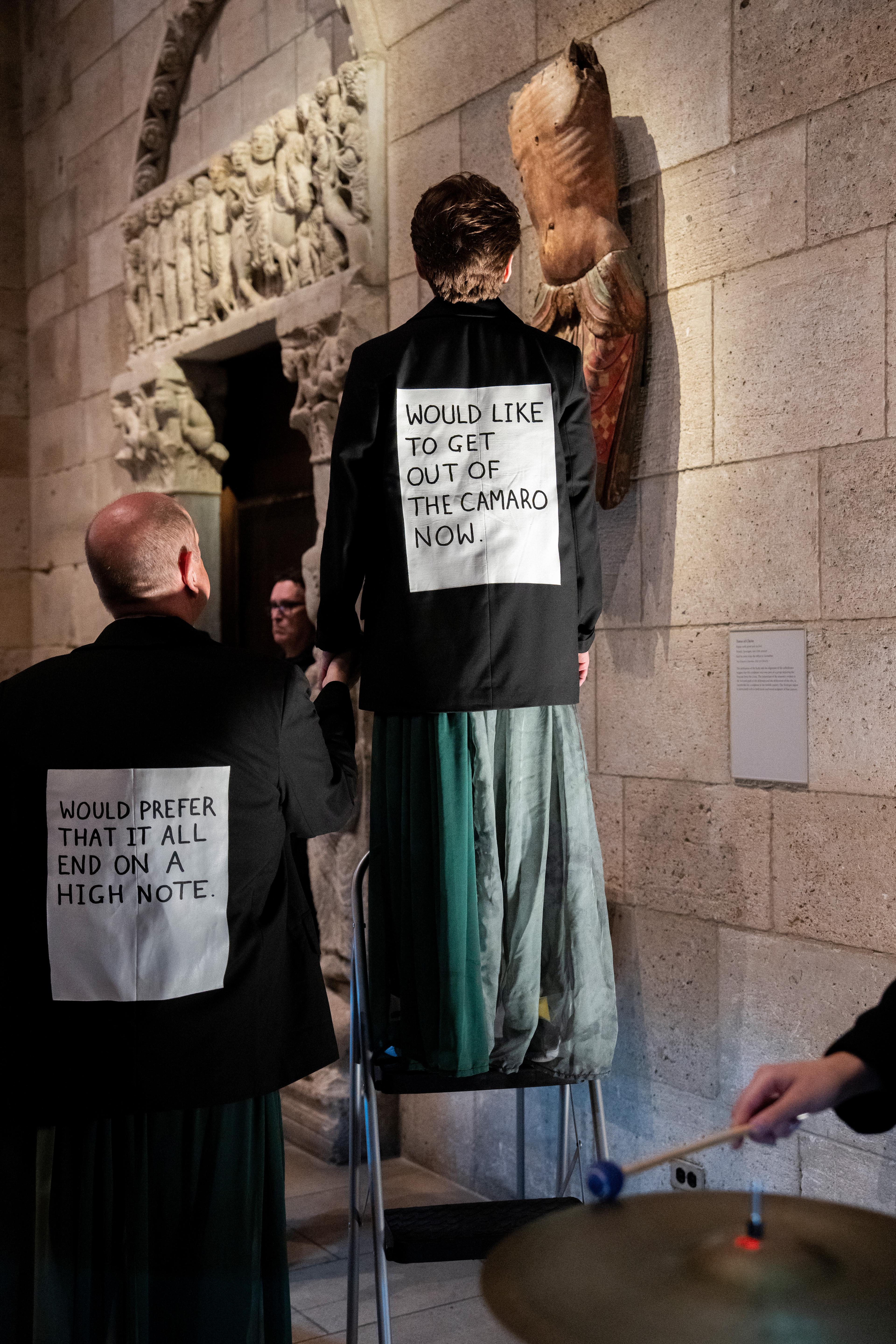

As the audience comes up the Postern entrance stairs, it’s their first introduction to both the music and the actors. We don’t really have any spoken language in the piece, but as the audience comes up the first staircase toward the different galleries, all of our actors and musicians have jackets on. The backs are gesso painted, and painter-poet Todd Colby has written these fun, amusing, enigmatic, little sentences—so absorbing those sentences is your handshake to Todd.

Actors wearing costumes by Liv Rigdon and Todd Colby. Text-based art by Todd Colby. © Stephanie Berger

Parson:

We’re searching for the piece in rehearsal. We only know what the physical actions will be—or rather, a first draft of what the physical actions will be—and we start to notice things. These actors are seekers. These are perhaps a tribe or a club or a clan or a small sect of people that have rituals, and these rituals have been passed down forever.

And then who are we within that? What is the tone? What is our relationship to these ritual acts? What we’re learning is that there’s a dailiness to the physicality, because you’ve done it hundreds of thousands of times. It’s almost like a nun in a convent—they know exactly how the day will unfold. They have certain prayers at this particular time, then they walk down this hallway, then they bow in front of this bowl, and they put their fingers in water. And it happens over and over and over again, so there’s not a lot of energy or effort around it. It’s so easy because they’ve been doing it forever, and they’re carrying a tradition that they’ve been taught. There’s nothing like that should feel generative about it. It should feel more like a dailiness.

But in our case, the thing that we’re making has highly complicated rules, and they won’t really be very familiar to anybody. There will be this code that all the performers understand, and the audience is learning the vocabulary as they go.

Actors and Members of the University of Michigan Percussion Ensemble in the Postern entrance. © Stephanie Berger

Lazar:

The ritual has a relationship to the music on a pragmatic level, finding the sounds that cue the shifts in ritual. It’s a very practical relationship, not unlike when the noon bell rings as a call to prayer. And then there’s also the more deep, resonant relationship to the music, which is that it’s kind of underscoring these rituals. When you watch people move through space while hearing the music, you hear and see differently.

Parson:

It always seems to me that when I work with musicians, they have a whole series of rituals that I don’t understand. But I see them, and they understand them. They do them all the time. They don't make a big deal of them. And I have a feeling that there’ll be a complementary sort of vibe between the musicians actually doing their work and us doing ours. It should feel in sync.

Kerekes:

Tell me about your approach to site-specific work. When you’re drawing inspiration from a space like The Met Cloisters, what do you latch onto? How do you translate that into performance?

Parson:

There’s the form and the content, which are very braided at the Cloisters. There’s the building itself, and all the sensory elements it creates—how a certain kind of stone has a certain sound and footfall. There’s the shape of the rooms, and then there’s the art. But there’s also the nature of the effort that you feel at the Cloisters, that this place and this art is so important that it was brought here and resited. It has a kind of preciousness—not precious like silly, but rare. And I think that’s where our ideas have come from about creating this sort of sect. I don’t want to use the word religious exactly, because there’s nothing religious about what we’re doing—except that there is definitely an inspiration underneath it, from the religiosity and spiritual nature of the material that we’re among. It couldn’t be anywhere else.

In performance in the Fuentidueña Chapel. © Stephanie Berger

Lazar:

In our lives as urban dwellers, especially in New York, we spend a great deal of time in small interiors whose edges are pretty geometrical—flat walls and right angles. Suddenly, we enter a space where every room is four to five times larger than what our bodies used to. You breathe differently. Your sense of space is inherently heightened. It’s theatrical, just to walk across a room like that.

Parson:

But it’s not holy—it feels closer to task-based work, which to me has a spirituality to it. Like they say: the highest priest in the temple does the lowliest task.

Kerekes:

This idea of “immersive art” gets tossed around a lot these days. What’s your concept of immersiveness? What does it add to the audience experience?

Parson:

I didn’t even think of the word to describe what we’re doing—maybe because it’s been co-opted. It’s the latest trend.

Lazar:

Yeah, it’s been corporatized, and people are paying hundreds of dollars. And, you know, I’m very jealous of the profit aspect of what immersive theater has become. But in the case of this piece, immersion has a very particular meaning, because the audience is immersed in sound.

Gordon:

That’s one of the things I'm very interested in as a composer: where the sound comes from. Music can be played from a 360-degree perspective. It can come from far away, from close up, from any direction. This is something I’ve been working with as a composer over the last decade and a half. I think about it almost like perspective in painting—from Giotto, the whole history of painting is adding dimension. We haven’t really done that so much in music.

I’ve never been to a concert that expands the dimensionality of the concert experience in quite this way, where I’m able to simply walk through the piece. It’s not just happening on the stage over there, and I’m just in my seat. I’m actually moving. The performers are moving. The musicians are moving. Everything is revolving and rotating.

It requires us to activate the audience in a certain way. Going to a concert is a fairly passive thing. You sit there in the chair, things happen, and you take it in. Here, we’re asking the audience to enter a different space, to move around, to be open to what’s happening. They’re not necessarily going to know what is happening, where they’re going, how long they’re going to be there for—it’s a magical tour in a certain sense, and we really are the guides.

Actors in performance in the Cuxa Cloister. © Stephanie Berger

Kerekes:

Tell me about some of the unique advantages and challenges of working in The Met Cloisters.

Parson:

With The Met Cloisters, my choreographic desire is to animate the architecture—and usually, that has to do with physically contacting it. Here, you can’t touch anything. But the benefits that you reap from being in a building like that that has so much vibe, so much history, are amazing. I mean, that is our set design: the Cloisters. It’s really hard to go back into a theater.

Lazar:

This was not our first time working in a museum setting. We made a fictitious museum tour at the Menil Collection in Houston. We had to relate to these constraints in as flexible and inventive a way as we could. As the famous avant-garde director Richard Foreman said: “Exploit the negative.”

Kerekes:

Say an audience member comes into The Forest of Metal Objects with no prior context. What would you want them to take away from the experience?

Parson:

I want them to have an experience that is their own, to check in rather than check out. I want them to hear the music as a frame. For the space, the actors, our work. So I want them to hear the music as it suits their own sensibilities, and to have their own experience.

Lazar:

The bulk of the music is played in the large, striking Cuxa Cloister, and the structure of Cuxa is such that the performers stand within this rectangular parapet wall, and the audience is outside of it. Every view—and every aural experience—of the action is going to be different from the person next to you. And sonically, the musicians are distributed in a way that it really is a different sound depending where you are in the cloister.

John Cage has a quote: “Everything we do is music, and everywhere is the best seat.” So when Annie-B says that she wants them all to have their own experience, that’s a more specific statement—it’s actually kind of a sonic journey that’s really particular to where your body happens to be at a given moment.

Gordon:

When someone is really stimulated by a piece of art, they invest their consciousness or subconsciousness into the experience, into listening or viewing or following the narrative or listening to the words. Our aim is to achieve that in a total way, so that it feels like the audience has really traveled inside of something.

And one other thing—sixteen is a lot of musicians, and the sound is coming from all directions and all points. Being completely selfish as a composer, I hope that people’s listening perspective becomes filled with more depth and more colors and and people go, “Oh, I see there’s sound that’s close, there's sound that’s far, there’s sound that travels, there’s sound that surrounds you, and there’s sound that’s in the distance.” I think that’s something you can’t hear from your seat at a concert hall.