The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are the most turbulent period in Japanese history, as military warlords clash violently and frequently in attempts to increase their own power and territory. The era when members of the Ashikaga family occupy the position of shōgun is known as the Muromachi period, named after the district in Kyoto where their headquarters are located. The Ashikaga government, or bakufu, never succeeds in extending wide political control, as had their predecessors of the Kamakura era. Rivalry between contending daimyo, or provincial warlords, causes increasing instability, which culminates in the Ōnin War (1467–77). With the resulting destruction of Kyoto and the collapse of the shōgunate’s power, the country is plunged into a century of warfare and social chaos known as the Sengoku, the Age of the Country at War.

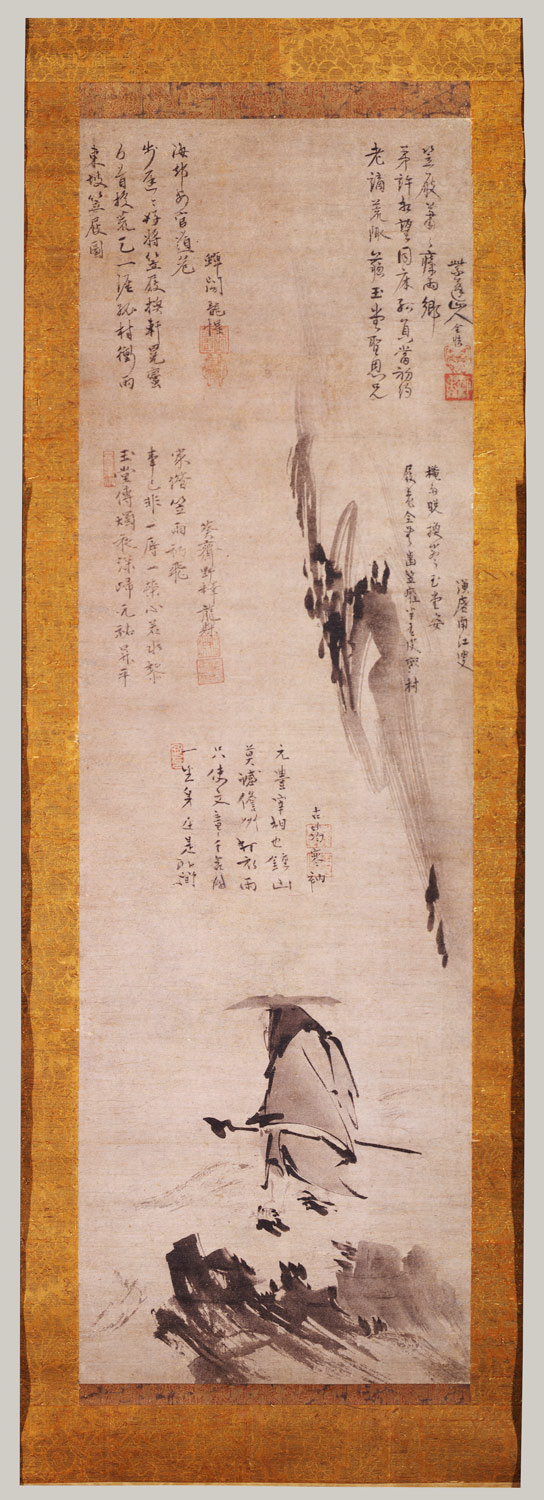

The cultural legacy of the Ashikaga shōgunate is the pervasive influence of Zen Buddhism in Japanese culture. Without Zen, such ancillary arts as the tea ceremony (chanoyu), flower arranging (ikebana), the Nō dance-drama, and the code of conventions and formal etiquette that characterizes modern life in Japan either would not have come into existence or would have taken very different forms from those that prevail today.

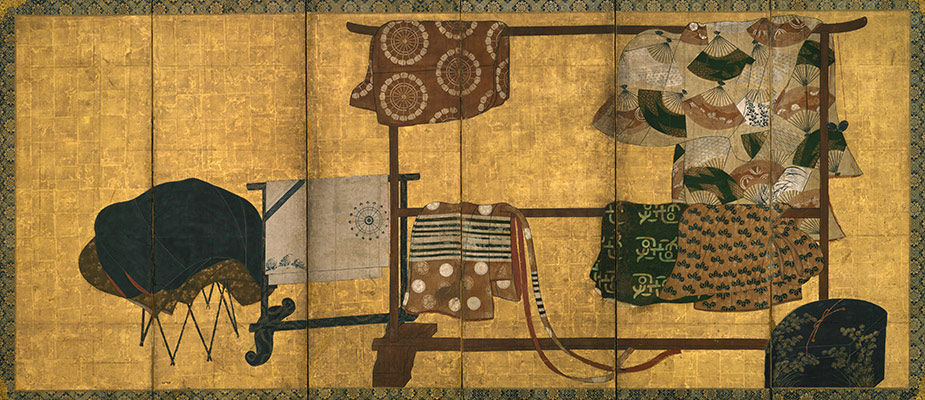

During the sixteenth century, unity is gradually restored through the efforts of three warlords. The first, Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582), through military might and political acuity, takes control of Kyoto and deposes the last Ashikaga shōgun. He is followed by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536–1598), who continues the campaign to reunite Japan. The name of this period, Momoyama, derives from the place near Kyoto where Hideyoshi builds one of his castles. These imposing stone structures are abundantly decorated with bold and resplendent paintings and works of art that epitomize the might of their owners and the splendor of Momoyama culture.