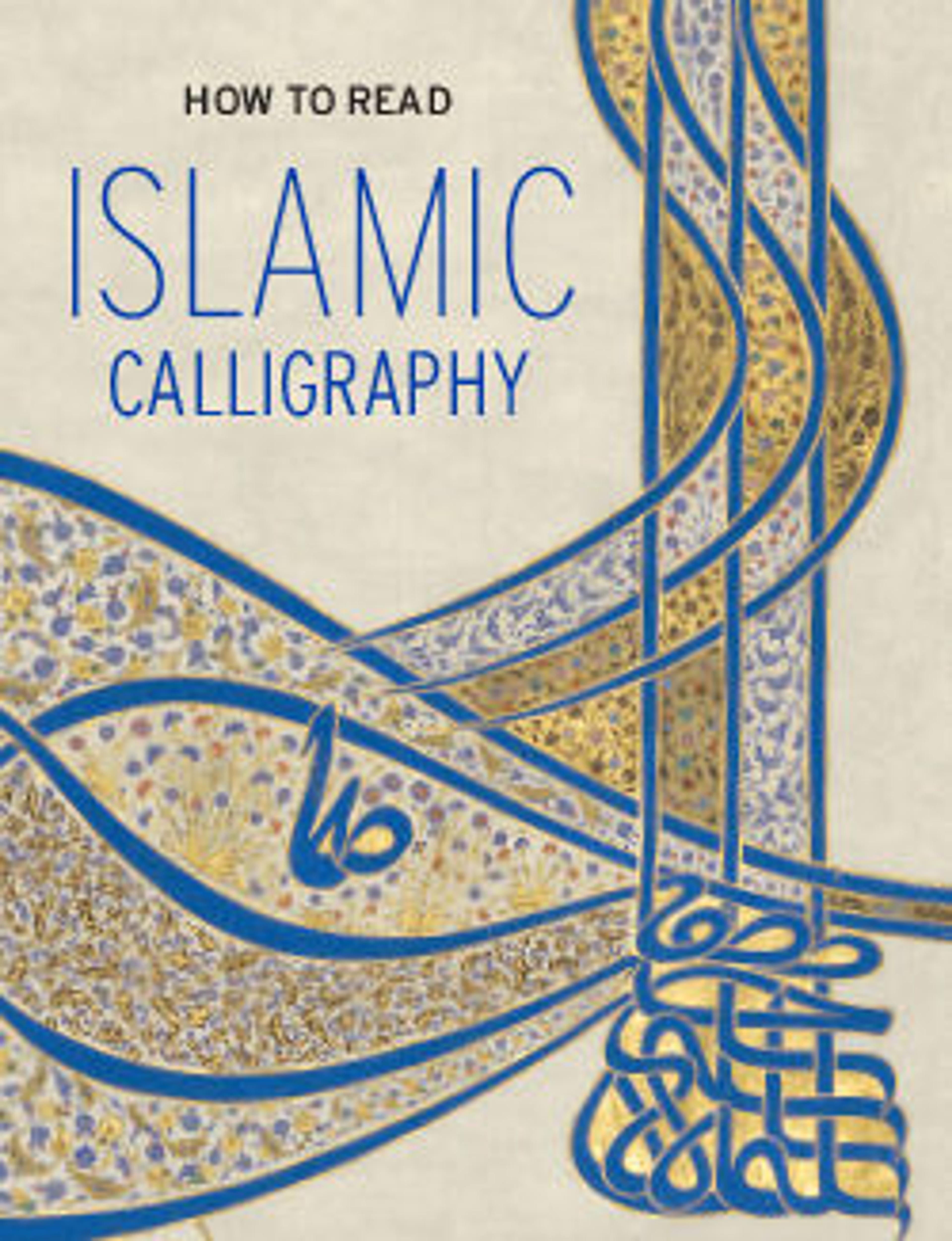

Section of a Qur'an

This manuscript is from the second volume of a luxurious Qur’an in which all 274 folios are elaborately illuminated. The text is written in a variation of thuluth script, with gold ink outlined in black and complemented by gold, red, and blue diacritical marks. Illuminated disks indicate verse endings and other denominations. In one of the folios a six-pointed star marks when the worshipper should perform a prostration. It reads sajda, or "prostration".

Artwork Details

- Title: Section of a Qur'an

- Date: 13th century

- Geography: Attributed to Egypt or Syria

- Medium: Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

- Dimensions: H. 20 in. (50.8 cm)

W. 13 1/4 in. (33.7 cm)

D. 2 3/4 in. (7 cm) - Classification: Codices

- Credit Line: Fletcher Fund, 1924

- Object Number: 24.146.1

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.