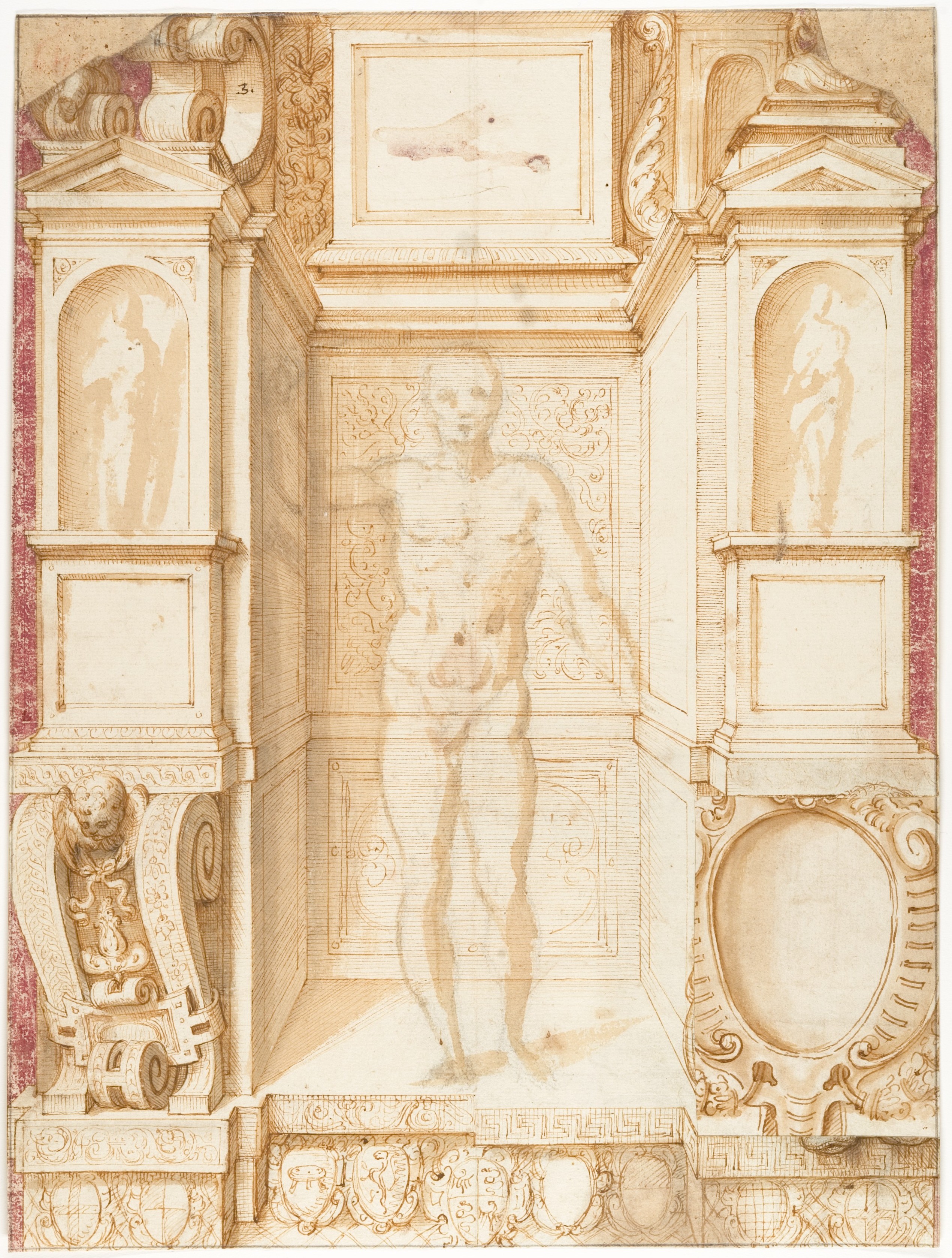

Study of a Figure in a Niche (Saint Ambrose; recto); Architectural Studies: Four Alternative Designs for Fictive Niches and an Unrelated Design with Garlands (verso), ca. 1560-67

Giuseppe Arcimboldo Italian

Not on view

The attribution to Arcimboldo of the Metropolitan Museum drawing was first suggested by Giulio Bora (cited in Christie's sale catalogue, London, July 4, 1995, lot 37; see also Bora 1998 with its whereabouts listed as "già a Londra"), and was recently reaffirmed by Giuseppe Cirillo, as it is entirely convincing on the basis of style, technical evidence, and context of the documents here discussed.

Datable to ca. 1560-67 and once owned by the distinguished Milanese collector Giuseppe Vallardi (1784–1863), the Metropolitan Museum drawing relates to the design of a prestigious, though much disputed commission by the Municipio (town-hall) of Milan for a banner representing Saint Ambrose, the heroic patron of the city who is also one of the canonical Doctors of the Church. The ambiguous scenario emerging from the interpretations of the surviving documents indicates that Arcimboldo may have ceded this project to design a banner of Saint Ambrose at the time of his departure from Milan in 1562 for the court of Prague, and that the commission may have been passed onto Carlo Urbino on February 18, 1563, for a document of this date describes the latter artist "as having assumed the job of making a design to be painted on paper and on cloth for the new banner" ("ha preso la carica de fare in pittura in carta et tela il dissegno dil nuovo confalone"; Archivio Storico Civico, Località milanesi, S. Ambrogio, Gonfalone, no. 309/4 [18 febbraio 1563]; here, as transcribed by Robert S. Miller, "Gli affreschi cinquecenteschi: Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Giuseppe Meda e Giovanni Battista Della Rovere detto il Fiammenghino," in Il Duomo di Monza: La storia e l’arte, 2 vols. Milan, Electa, 1989-1990, p. 226).

The documents also tell that the final execution of the banner was to be done by the embroiderer Bartolomeo Rainone, but the entire project was interrupted in 1564, amidst a heated professional controversy, of which modern scholars have given different accounts (compare opinions in Giulio Bora, "Note cremonesi, II: L'eredità di Camillo ed i Campi," Paragone, no. 327 [May 1977], pp. 54-88; Giulio Bora in Omaggio a Tiziano: La cultura artistica milanese nell'età di Carlo V, exh. cat., Milan, Palazzo Reale, Milan, 1977, pp. 52-54 [notes 58-61], 62-86; Sandrina Bandera Bistoletti in Daniele Pescarmona, Disegni Lombardi del Cinque e Seicento della Pinacoteca di Brera e dell'Archivescovado di Milano, exh. cat., Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan; Florence, 1986, pp. 92-96; Miller 1989-90, op. cit., pp. 216-28, note 48; Bora 1998, op. cit., pp. 52-55; Cirillo 2005, op. cit., pp. 57-59). From what can be discerned, a casual mention in the legal complaint filed on November 6, 1564 to the Fabbriceri del Duomo of Milan regarding another project, the prestigious commission to paint the organ shutters of the Cathedral entrusted to Giuseppe Meda, partner ("compagno") of Arcimboldo, also seems to shed light on the design of the banner of Saint Ambrose, the project to which the Metropolitan Museum drawing actually relates, as this latter document alludes to a repeatedly competitive situation between Bernardino Campi and Arcimboldo ("in diverse volte a concorentia") regarding the banner of Saint Ambrose ("Sant’Ambrogio"), and to a dispute which was to be settled by the artists' submission of their respective designs to a corporate tribunal (the "Dodici del Tribunale di Provvisione"). This document about the banner of Sant’Ambrogio is in the Archivio della Fabbrica del Duomo di Milano (Ordinazione, XII, fols. 124 recto-125 recto; Miller 1989-1990, op. cit., pp. 216, 227, note 1). The judges ("stimatori") on behalf of the Fabbriceri del Duomo were Giovanni Francesco Melzi (pupil and heir of Leonardo) and Girolamo Figino, who also ruled that the drawing for the "confalone del nuovo S.to Ambroso" by Giuseppe Arcimboldo, who was in partnership with Giuseppe Meda, was far superior to the design by Bernardino Campi, and that Arcimboldo’s was the design chosen for execution. The wording of these documents provides unmistakable proof, "fu per li predicti signori Meltio et Figino indicato il disegno desso Bernardino [Campi] essere molto inferiore al disegno desso magistro Joseph [Giuseppe Arcimboldo] qual fu acetate et messe in opera" (here, as transcribed in Miller 1989-90, op. cit., pp. 216, 226, but also quoted very diversely in Enrico Cattaneo et al., Il Duomo di Milano, Milan, 1973, vol. 2, pp. 193-97; Bora 1977, op. cit., p. 52; Bandera Bistoletti 1986, op. cit., p. 92; and Bora 1998, op. cit., p. 41). The redesigned banner of Sant’Ambrogio was contracted to be executed (document July 14, 1565) by the more skilled embroiderers Scipioni Delfinone and Camillo Pusterla (than Rainone), who were to follow the drawing that was provided. Although completed in early September 1566, Arcimboldo collected two payments on 10 October and 30 December 1567, "for the first drawings made for the said banner" ("per i primi dissegni fatti del sopradetto confalone"). The banner of Sant’Ambrogio is today on display in the Civiche Raccolte d'Arte of Castello Sforzesco, Milan.

The Metropolitan Museum drawing must have been one of the early studies by Arcimboldo for his winning competition drawing of the "nuovo confalone," or new banner. For, confirming the scenario implied in the documents, there exists a large, relatively dry, more or less finished composition drawing much like the final banner in design, now in the Arcivescovado, Milan ([inv. 36], done in pen and brown ink, brush and brown wash, highlighted with white gouache, on ochre prepared paper; 54,5 x 37,5 cm.). Although this sheet in the Arcivescovado, Milan, has been repeatedly published with an attribution to Bernardino Campi (as illustrated and discussed in Bora 1977, op. cit., pp. 84-85, no. 52; followed in Bandera Bistoletti 1986, pp. 92-96, no. 31), it is almost certain that the alternative attribution to Giuseppe Meda, as advanced by Robert Miller, is correct (Miller 1989-90, pp. 216-230 [especially p. 225, fig. 195]; accepted in Bora 1998, p. 40, fig. 3; Cirillo 2005, p. 58). In any case, it can be added here that the papers of the drawings in the Arcivescovado, Milan, by Giuseppe Meda and Metropolitan Museum of Art by Arcimboldo exhibit similar watermarks, a hand surmounted by a star; the first is close to Briquet 10719-10720, while the Metropolitan sheet is close to Briquet 10796. Meda’s somewhat lifeless and rather harshly modelled drawing in the Arcivescovado, Milan (which is nevertheless clearly an autograph study for the banner, not a copy) offers an elaboration of details of the key iconographic elements as they are represented in the final banner today at the Castello Sforzesco. These iconographic motifs are also indicated, though in a more inchoate form, in the energetic overall composition of the drawing by Arcimboldo in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Without doubt, however, the design and the details of the figure and ornament in the drawing by Giuseppe Meda in the Arcivescovado, Milan, seem closer to the composition of the final banner at the Castello Sforzesco, than is the Metropolitan Museum drawing by Arcimboldo.

The driving concept in Arcimboldo's design for the banner is the architectural setting for the figure, which is of great monumentality. His Metropolitan demonstration drawing (a type of early "modello") offers two alternative solutions for the illusionistic architectural framework at the sides; this "de choix" feature of the design is often characteristic of drawings for the approval of patrons. On the left half, the small pedimented niche and podium are surmounted by variations of volutes and supported by a monumental, elaborately carved console. Rectilinear elements predominate on the right half of the sheet, but their precise disposition is difficult to judge, since another artist excised a square piece of the drawing and replaced it with the unrelated design of a cartouche. In contrast to the architecture, the figures are broadly painted with light brown wash. The large sketchy nude figure in the center raises his right hand in blessing, as the fully garbed Saint Ambrose does in the final banner at the Castello Sforzesco. The heraldic symbols at the bottom of the Metropolitan drawing, including the coat of arms of the Sforza-Visconti family at center, below the main niche, all seem to conform to those depicted in the final banner, and apparently also to those in Meda’s drawing in the Arcivescovado, Milan.

Although evidencing a particularly close study of Giulio Campi's draftsmanship (in my opinion), the style and technique of the architectural drawings on the main paper support of the verso of the Metropolitan sheet are also clearly attributable to Arcimboldo, as they are exactly comparable to the ornamental passages along the lower border of the recto. These isolated designs of rectangular niches and ornamented pediments on the verso of the Metropolitan sheet were also intended for the fictive architecture flanking Saint Ambrose, and are very similar to the lateral designs portrayed in Meda’s drawing in the Arcivescovado, Milan, and in the final banner today in the Castello Sforzesco. But these verso drawings are much disfigured by the distracting patch containing unrelated designs glued onto the sheet (seen at lower left, on the verso) by a different hand, facts which may be overlooked if this drawing is only studied from photographs.

(Carmen C. Bambach)

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.