Inuit Manner of Dress

Jean-Baptiste Le Prince French

Not on view

While the French artist Jean-Baptiste Le Prince is most well-known for his images of the Russian Empire, through which he traveled between 1757 and 1763, this drawing purports to depict Greenlandic Innuits. It was engraved for volume nineteen of the encyclopedic travel compilation, Histoire Générale des Voyages (1770), which also published Le Prince’s drawing, "Itelmens Preparing Fish to be Dried" (2012.53), in its section on Kamchatka.(1)

Le Prince himself never visited Greenland. Instead, he adapted earlier illustrations from European accounts of expeditions to the Arctic north, including David Cranz’s Historie von Grönland (1765), which was translated into French that same year and English in 1767, and possibly Allain Manesson Mallet’s Description de l'univers, contenant les différents systèmes du monde, les cartes générales et particulières de la géographie ancienne et moderne, les plans et les profils des principales villes et des autres lieux plus considérables de la terre (1683).(2)

Cranz (1723-1777) was a German Moravian missionary, minister, and historian who stayed fourteen months beginning in 1761 at the Moravian mission station, Neu-Herrnhut, in West Greenland. While there he interacted with the Inuits who lived in the area, the Kalaallit, whom he later illustrated in his book.(3) His engraving, which presents a Kalaallit man and woman in two separate scenes, printed on the same page, served as the basis for Le Prince’s depiction of their dress and customs, including such details as the woman’s necklace and basket.(4)

Le Prince reworked these original depictions of Greenland, transforming them into eighteenth-century Rococo illustrations that would appeal to his French audience. Most importantly, he fused the individual figures from separate images into a familial group. Adding physical interaction and a bit of drama, he converted static studies of costumes into a genre scene and intimated a story. The man, now a father, attempts to draw the woman’s attention to the boats on the water as he turns to speak to her. Responding neither to her partner’s entreaty or the baby’s motion at her back, the woman appears lost in thought, almost saddened, with her eyes cast downwards.

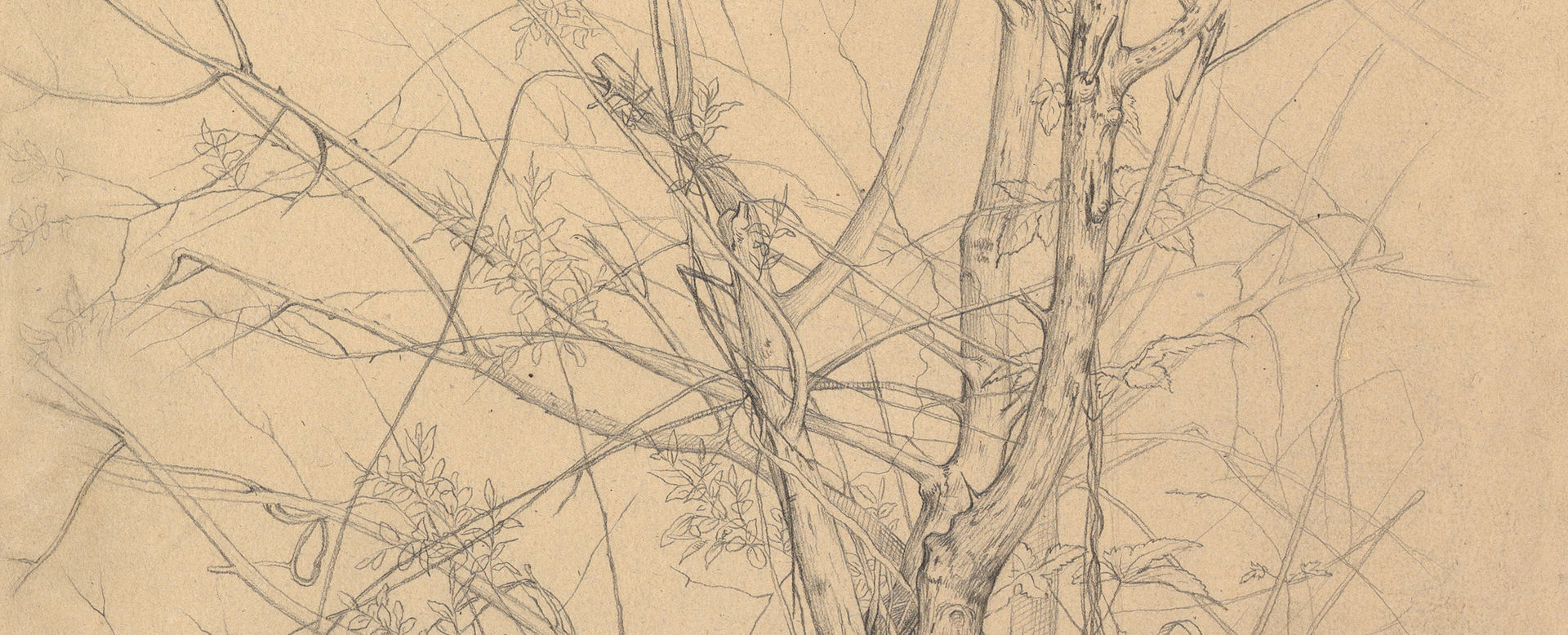

At the same time, Le Prince removed many of the specific details of Kalaallit culture that Cranz included in the original engravings, such as the different types of lodgings the Kalaallit built and the various types of wildlife they hunted. Le Prince also added new invented details in graphite to the finished ink drawing, including the leafy bush behind the kayak and the cloth hanging from the woman’s basket. Included in the final print, neither feature has a precedent in Cranz’s images. Le Prince also made notable changes to the Kalaallits’ physiognomies, most visibly in the woman’s features. Pencil marks around the faces, especially the around the curves of their cheeks, indicate Le Prince struggled with their profiles, which diverge from eighteenth-century French conventions for drawing faces. By contrast, Cranz’s figures had conventional European faces. Le Prince’s transformation of Cranz’s plates thus accentuated the exoticism of the figures by introducing changes in physiognomy while at the same time presenting such differences within the familiar framework of a domestic genre scene.

(1) The series was originally commissioned as a translation of John Green’s New General Collection of Voyages and Travels (London, 1745-1747) but soon outgrew the English material. Between 1745 and 1761, Abbé Prevost edited the original sixteen volumes. Anne-Gabriel Meusnier de Querlon and Rousselot de Surgey published a continuation of the series, volumes seventeen through nineteen, between 1761 and 1770. Abbé Prévost, Anne-Gabriel Meusnier de Querlon, and Rousseleot de Surgy, Histoire générale des voyages, ou, Nouvelle collection de toutes les relations de voyages par mer et par terre, qui ont été publiées jusqu'à present dans les différentes langues de toutes les nations 19 vols. (Paris: Chez Rozet, 1746-1770), 19: 71.

(2) David Cranz, Historie von Grönland enthaltend die Beschreibung des Landes und der Einwohner &c. insbesondere die Geschichte der dortigen Mission der Evangelischen Brüder zu Neu-Herrnhut und Lichtenfels 2 vols. (Barby: Heinrich Detlef Ebers, 1765-1770); and David Crantz, The history of Greenland: containing a description of the country, and its inhabitants: and particularly, a relation of the mission, carried on for above these thirty years by the Unitas Fratrum, at New Herrnhuth and Lichtenfels, in that country (London: Printed for the Brethren’s Society for the Furtherance of the Gospel among the Heathen, 1767).

(3) Felicity Jensz, "The Publication and Reception of David Cranz’s 1767 History of Greenland," The Library: The Transactions of the Bibliographical Society 13 (2012): 457-472.

(4) The woman is likely wearing glass beads that the Inuit purchased from the Moravian missionaries or nearby Royal Greenlandic Trading Department Stores. Such beads are frequently found in the archeological sites of the missions. Intriguingly, this suggests Cranz documented not an Inuit pre-contact tradition but rather a trans-cultural fashion produced by the Inuits’ trade with Europe. In contrast, Le Prince rendered the components of the necklace larger, more rectangular, and less delicate. See Peter Andreas Toft, "Moravian and Inuit Encounters: Transculturation of Landscapes and Material Culture in West Greenland," Arctic 60, Supp. 1 (2016): 1-13.

(Thea Goldring, May 2021)

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.