Egyptian Art

About Us

The Met’s collection of ancient Egyptian art consists of approximately 30,000 objects of artistic, historical, and cultural importance, dating from about 300,000 BCE to the fourth century CE. A significant percentage of the collection is derived from the Museum's three decades of archaeological work in Egypt, initiated in 1906 in response to increasing interest in the culture of ancient Egypt.

The Department of Egyptian Art was established in 1906 to oversee the Museum's already sizable collection of art from ancient Egypt. In the same year, the Museum's Board of Trustees voted to establish an Egyptian Expedition to conduct archaeological excavations in Egypt. Between 1906 and 1935, The Met's Egyptian Expedition worked at a number of important sites, including Lisht in the north and Thebes in the south, and the objects gifted to The Met by the Egyptian antiquities service form the core of our collection. Over the years, the Department of Egyptian Art has also been able to acquire, through purchase and bequest, several important private collections.

In addition to interpreting and caring for the permanent collection of ancient Egyptian art, the staff of the Department of Egyptian Art continues to excavate at the Museum's concessions in Egypt under the oversight of the Supreme Council of Antiquities of the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

For further reading on the history of the department, see Making The Met: 1870-2020 and this essay.

When the Lila Acheson Wallace Galleries of Egyptian Art opened in 1983, the goal of the new installation was to present The Met's entire collection of Egyptian art. Today, most of the collection remains on view in thirty-eight galleries for the visitor's enjoyment. These galleries are organized so that a visitor moving through them can "travel" through Egyptian history, starting with the rise of the state in the Predynastic Period (ca. 4500 BCE), presented in Gallery 101, and ending in Gallery 138 with the last phase of Rome's occupation of Egypt (CE 400).

Several galleries emphasize particular themes within this chronological framework, drawing the visitor's attention to important tomb groups, objects that reflect daily life, or fascinating funerary traditions. Set in the context of Egyptian history, these objects reflect the aesthetic values, religious beliefs, and everyday life of the ancient Egyptians over the approximately 5,000 years this remarkable civilization existed. The collection is particularly well known for the Old Kingdom offering chapel of Perneb's mastaba in Gallery 100 (ca. 2450 BCE); a set of delicate wooden models from the Middle Kingdom tomb of Meketre in Gallery 105 (ca. 1990 BCE); the incomparable jewelry of Princess Sithathoryunet of Dynasty 12 in Gallery 111 (ca. 1897–1797 BCE); royal sculpture of the Middle Kingdom in Gallery 111 (ca. 1991–1783 BCE); temple statues of Dynasty 18's female pharaoh Hatshepsut in Gallery 115 (ca. 1473–1458 BCE); and the nested coffins of Dynasty 21 in Gallery 126 (ca. 1070–945 BCE). In 2016, the galleries of Ptolemaic art (ca. 332–30 BCE) were reinstalled and this important collection is displayed to great advantage in the floor to ceiling cases of Gallery 134.

The department also exhibits its invaluable collection of tempera or ink facsimiles that faithfully reproduce paintings in ancient Egyptian tombs. These were largely produced between 1907 and 1937 by members of the Graphic Section of the Museum's Egyptian Expedition. Each year, a thematic selection of these facsimiles is displayed in Gallery 132 as a small exhibition.

Click here for more information about our departmental rotations.

The Temple of Dendur is a destination for Met visitors. Completed by 10 BCE, the Roman emperor Augustus — who had succeeded Cleopatra VII, the last of the Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt — commissioned this temple to honor the great goddess Isis. Worshipped here as well were two brothers, sons of a local Nubian ruler; the esteem in which the brothers were regarded in this region, about fifty miles south of modern Aswan, may explain why Augustus chose Dendur as a place to erect a temple. During The International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia, the 2,000 year old temple was dismantled to protect it from the rising waters of Lake Nasser following the completion of the Aswan High Dam. The government of Egypt presented the Temple of Dendur as a gift to the people of the United States in recognition of the American contribution to this historic campaign.

Art

Articles, Audio, and Video

Featured

The Latest

Research

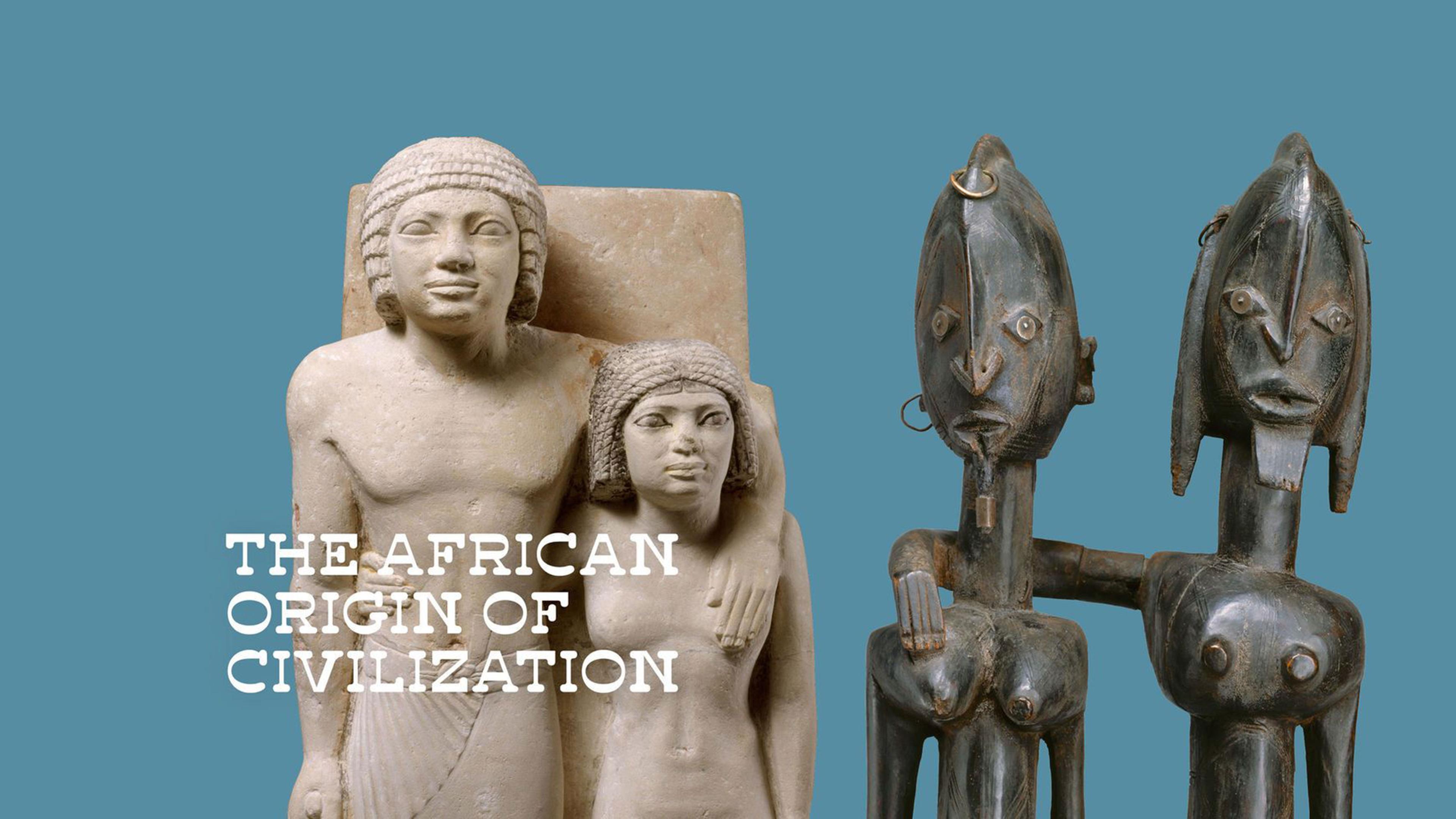

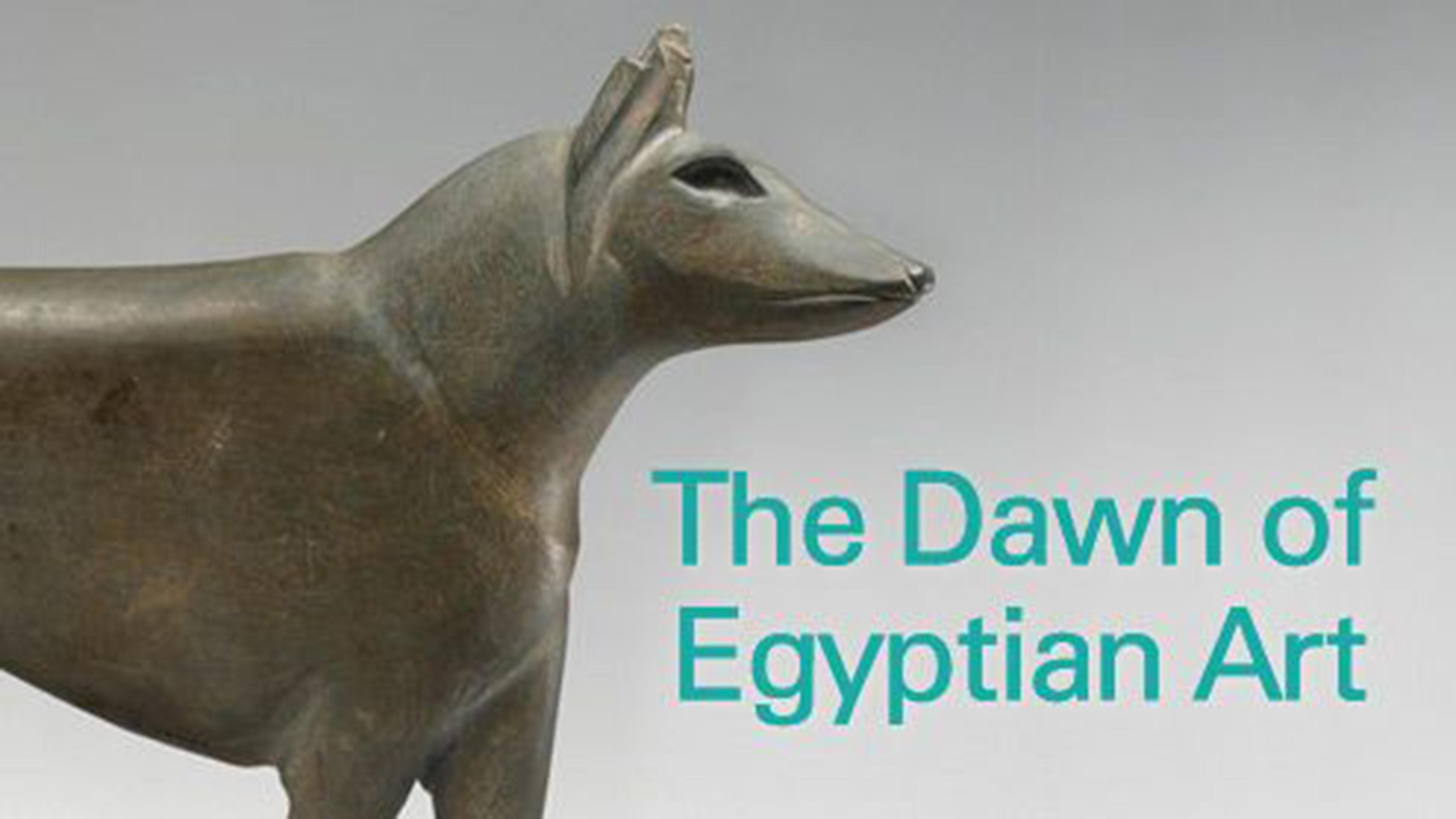

Exhibitions

Press the down key to skip to the last item.